James Barry, an artist of formidable intellect, ambition, and a notoriously difficult temperament, remains one of the most compelling and controversial figures in the history of British and Irish art. Born in Cork, Ireland, on October 11, 1741, and passing away in London on February 22, 1806, Barry's life was a tumultuous journey marked by grand artistic visions, significant achievements, and ultimately, bitter conflict with the very institutions he sought to elevate. His unwavering belief in the moral and didactic power of historical painting placed him at odds with prevailing tastes, yet his legacy endures as a testament to an artist who dared to pursue a monumental and often thankless path.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings in Ireland

James Barry's origins were modest. He was born in a small cottage in Water Lane (now Seminary Road), Cork, to Juliana Reardon and John Barry. His father was a builder and later a coastal trader, captaining his own vessel. Initially, it was expected that young James would follow his father into the maritime trade. However, from an early age, Barry exhibited a profound disinterest in this path, instead displaying an insatiable appetite for learning and a burgeoning passion for drawing and painting.

His early education in Cork provided him with a solid grounding, but his artistic inclinations soon led him to seek more formal training. He is believed to have received some instruction from a local artist, possibly John Butts, a landscape and figure painter of some repute in Cork. Barry's precocious talent was evident; stories abound of his youthful dedication, including an alleged early sea voyage where he spent his time sketching rather than attending to nautical duties, much to his father's chagrin.

Recognizing his son's undeniable calling, John Barry eventually relented. James moved to Dublin around 1763, where he continued his artistic studies. It was here that his work began to attract attention. An early historical painting, The Baptism of the King of Cashel by St. Patrick (also known as St. Patrick Baptising the King of Cashel), showcased his ambition to tackle grand themes rooted in Irish history and legend. This piece, exhibited in Dublin, brought him to the notice of influential figures.

The Patronage of Edmund Burke and the Italian Sojourn

The most significant encounter of Barry's early career was with the Irish statesman, philosopher, and writer Edmund Burke. Burke, a man of immense intellectual capacity and a keen supporter of the arts, recognized Barry's raw talent and intellectual fervor. In 1764, Burke, along with his kinsmen William and Richard Burke, decided to sponsor Barry's artistic education, enabling him to travel to Italy, the crucible of classical and Renaissance art.

Barry's time in Italy, from 1766 to 1771, was transformative. He spent extensive periods in Rome, Florence, Bologna, and Venice, immersing himself in the study of antiquity and the High Renaissance masters. He was particularly drawn to the grandeur of Michelangelo, the grace of Raphael, and the rich colorism of Titian and the Venetian school. Unlike many of his contemporaries on the Grand Tour who focused on producing pleasing views or copies for the tourist market, Barry engaged in a profound intellectual and artistic dialogue with the past.

His letters to Edmund Burke from this period reveal a mind grappling with complex aesthetic theories and a burning desire to revive what he perceived as the declining state of historical painting in Britain. He was critical of the prevailing Rococo style, which he saw as frivolous, and championed a return to the "great style" characterized by noble subjects, moral purpose, and heroic execution. While in Rome, he would have been aware of the burgeoning Neoclassical movement, championed by figures like Anton Raphael Mengs and Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose writings on Greek art profoundly influenced the era. Barry, however, forged his own path, blending classical ideals with a more dynamic, almost proto-Romantic sensibility.

Return to London and the Royal Academy

Upon his return to London in 1771, James Barry was eager to make his mark. Armed with his Italian experiences and a fierce determination, he quickly sought to establish himself as a leading historical painter. The Royal Academy of Arts, founded just a few years earlier in 1768 with Sir Joshua Reynolds as its first President, was the focal point of the London art world. Barry exhibited works such as Adam and Eve (1771) and Venus Rising from the Sea (1772), which, despite some criticism for their anatomical idiosyncrasies, demonstrated his ambition and skill.

In 1772, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), and in 1773, he became a full Royal Academician (RA). This rapid ascent was a testament to his talent and the high regard in which historical painting was, at least theoretically, held. The Academy, under Reynolds's leadership, espoused the "Grand Manner," which prioritized historical, mythological, and biblical subjects as the noblest form of art. Barry, in principle, was perfectly aligned with these ideals.

His early years at the Academy were productive. He painted The Death of General Wolfe (completed c. 1776), a subject famously treated by his contemporary Benjamin West. While West's version achieved immense popularity for its contemporary portrayal of the figures, Barry's interpretation, though less known, was a powerful and dramatic composition, reflecting his classical training. He also produced Ulysses and Polyphemus (c. 1776), a dynamic and heroic scene from Homer's Odyssey, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and dramatic narratives.

The Great Room Murals: The Progress of Human Culture

Barry's most ambitious and arguably most significant undertaking was the series of six monumental paintings for the Great Room of the Royal Society of Arts (then the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) at the Adelphi. In 1774, a proposal for a group of ten artists, including luminaries like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Angelica Kauffman, Nathaniel Dance, and Benjamin West, to decorate the Great Room with historical and allegorical paintings had fallen through, partly due to disagreements among the artists.

Seizing the opportunity, Barry, in 1777, offered to undertake the entire project himself, without commission, driven by his fervent belief in the public and moral utility of art. He proposed a grand allegorical cycle depicting The Progress of Human Culture (or Human Improvement). The Society accepted his audacious offer, providing only the canvases, paints, and materials. For the next six years, from 1777 to 1783 (with some final touches in 1784), Barry labored almost single-handedly on this colossal project, often in dire financial straits.

The series consists of six vast canvases:

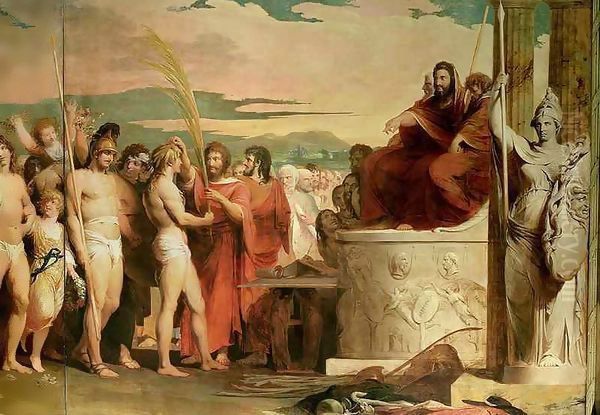

1. Orpheus Reclaiming Mankind: Representing the dawn of civilization through music and poetry.

2. A Grecian Harvest Home: Celebrating agriculture, peace, and rural festivity in ancient Greece.

3. The Victors at Olympia: A complex scene of athletic triumph, symbolizing the peak of Greek civilization, featuring portraits of contemporary figures like Dr. Charles Burney and Edmund Burke alongside ancient heroes.

4. Navigation, or The Triumph of the Thames: An allegorical depiction of British maritime power and commerce, with figures like Sir Francis Drake and Captain Cook.

5. The Distribution of Premiums in the Society of Arts: Showing the Society rewarding achievements in arts, manufactures, and commerce, a scene filled with portraits of prominent members and contemporaries, including a somewhat controversial inclusion of himself.

6. Elysium, or The State of Final Retribution: A grand assembly of virtuous and enlightened figures from history, philosophy, and the arts, gathered in the afterlife.

These paintings are a remarkable testament to Barry's erudition, ambition, and artistic power. They blend Neoclassical principles of composition and idealized form with a dynamic energy and intellectual depth that is uniquely Barry's. The iconographic program is complex, drawing on classical mythology, history, and contemporary life to create a sweeping panorama of human endeavor and enlightenment. Upon their completion, the paintings were generally well-received, and the Society of Arts awarded Barry its gold medal and a sum of 200 guineas. The public flocked to see them, and for a time, Barry's reputation soared.

Artistic Philosophy, Controversies, and Character

James Barry was a man of strong convictions and an unyielding, often abrasive, personality. He believed passionately that art should serve a high moral and intellectual purpose, educating and ennobling the public. He disdained what he saw as the commercialization of art and the prevalence of portraiture, which he considered a lesser genre, despite its lucrative nature for artists like Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Barry's ideal was the "historical painter" as a public intellectual and moral guide.

His lectures as Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy, a post to which he was appointed in 1782, became a platform for his often-controversial views. While learned and insightful, his lectures were also frequently used to critique the perceived failings of the Academy, its members, and the general state of British art. He was particularly critical of the Academy's financial management and what he saw as its insufficient support for historical painting.

Barry's outspokenness, his thin skin, and his tendency to see conspiracies and personal slights everywhere made him a difficult colleague. He clashed repeatedly with Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose more pragmatic and socially adept approach to art and patronage contrasted sharply with Barry's uncompromising idealism. He also alienated other Academicians, including the influential architect Sir William Chambers. His relationships with fellow artists were often fraught; while he respected figures like William Blake for their visionary qualities, and was a contemporary of Romantic pioneers like Henry Fuseli (who shared Barry's interest in the sublime and the terrible), his irascible nature often led to isolation.

He was not without supporters. Edmund Burke remained a steadfast, if often exasperated, friend and defender. Other artists, like the American-born Gilbert Stuart, whom Barry had recommended for study in Rome, and perhaps even the Irish painter Edward Calvert or the British artist George Cumberland, would have been aware of his powerful, if idiosyncratic, presence in the London art world. However, Barry's inability to compromise or to navigate the social and political currents of the art establishment proved to be his undoing.

Expulsion from the Royal Academy

The simmering tensions between Barry and the Royal Academy came to a head in the late 1790s. His increasingly vitriolic attacks on the institution and its members, both in his lectures and in published pamphlets, became intolerable to the Academy's council. He accused fellow Academicians of incompetence, corruption, and actively working against the interests of true art.

In 1799, matters reached a crisis point. Following a series of charges related to his conduct and his inflammatory publications, James Barry was formally expelled from the Royal Academy. This unprecedented and drastic measure effectively ended his official career and further isolated him from the mainstream art world. The expulsion was a devastating blow to Barry, who, for all his criticisms, deeply valued the ideals that the Academy, in his view, should have represented.

The expulsion highlighted the clash between Barry's uncompromising, almost fanatical devotion to his artistic principles and the more pragmatic, collegial, and perhaps at times, complacent, nature of the institution. Artists like Benjamin West, who succeeded Reynolds as President, or even the successful female Academician Angelica Kauffman, managed to navigate the system far more adeptly than the confrontational Barry.

Later Years, Poverty, and Legacy

The last years of James Barry's life were marked by increasing poverty, neglect, and eccentricity. He lived in squalor in his house on Castle Street, off Oxford Street, surrounded by his unsold paintings and engravings. Despite his hardships, he continued to work, producing engravings of his Society of Arts murals and other compositions. He also painted some notable later works, including a powerful self-portrait and portraits such as that of John Wesley, which, like many of his works, combined Neoclassical structure with a penetrating psychological insight.

His financial situation became so dire that in 1805, a group of sympathizers, organized by Sir Robert Peel (the elder), raised an annuity of £120 for him. However, he was not to enjoy this support for long. In early 1806, he was taken ill and died on February 22, at the age of 64.

In a final, ironic tribute from the establishment he had so often railed against, James Barry was granted a public funeral and burial in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral, near the tomb of his former adversary, Sir Joshua Reynolds. This honor acknowledged, perhaps belatedly, his significant contributions to British art, particularly his heroic dedication to the grand style of historical painting.

James Barry's legacy is complex. He was not a prolific painter, and his technical skills, particularly in anatomy and finish, were sometimes criticized even by his contemporaries. However, the intellectual power, moral seriousness, and sheer ambition of his major works, especially The Progress of Human Culture, are undeniable. He stands as a crucial figure in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism in British art. His emphasis on individual genius, the sublime, and the moral power of art resonated with later Romantic artists, even if his direct stylistic influence was limited.

Artists like William Blake admired his independent spirit, and his work would have been known to other Neoclassical and early Romantic figures such as John Flaxman, the sculptor and draughtsman, and perhaps even painters like John Singleton Copley, who also tackled grand historical themes. Barry's insistence on the artist's role as a public intellectual and moral force, though often expressed in a self-destructive manner, prefigured aspects of the Romantic conception of the artist.

Conclusion: An Uncompromising Visionary

James Barry remains a figure who elicits both admiration for his artistic vision and frustration at his personal failings. He was a man of immense talent and learning, dedicated to the highest ideals of art. His Society of Arts murals are a unique and monumental achievement in the history of British painting, a testament to one man's unwavering commitment to a grand, didactic artistic program.

His career serves as a cautionary tale about the difficulties faced by an uncompromising artist in a world often driven by patronage, politics, and shifting tastes. Yet, his fierce independence, his intellectual depth, and the raw power of his best works ensure his place as one of the most original, if tragic, figures of his era. He challenged the conventions of his time, striving to create an art that was not merely decorative but profoundly meaningful, and in doing so, left an indelible, if often overlooked, mark on the landscape of art history. His life and work continue to provoke discussion and re-evaluation, securing his status as a turbulent genius whose contributions are still being fully appreciated.