Introduction: A Painter of the People

William Powell Frith stands as one of the most significant and popular painters of the Victorian era in Britain. Born into a world undergoing rapid industrial and social transformation, Frith dedicated his considerable talents to capturing the vibrant, complex, and often contradictory tapestry of contemporary life. Unlike many of his peers who focused on historical, mythological, or purely allegorical subjects, Frith turned his gaze to the bustling crowds, public spectacles, and everyday moments of his time. His large-scale, minutely detailed canvases became visual encyclopedias of Victorian society, earning him immense fame and fortune, though also attracting criticism for their perceived lack of high artistic purpose. He remains a pivotal figure for understanding not just 19th-century British art, but the very fabric of the society he depicted with such meticulous care.

Frith's career spanned much of Queen Victoria's reign, a period marked by unprecedented change, technological advancement, and social stratification. His work provides a unique window into this world, from the sandy beaches thronged with holidaymakers to the chaotic energy of a race day, the organized bustle of a modern railway station, and the exclusive gatherings of the art world elite. He possessed an extraordinary ability to orchestrate vast numbers of figures, each rendered with individual character, into compelling narrative compositions. Often compared to literary giants like Charles Dickens for his observational acuity and storytelling prowess, Frith created images that resonated deeply with the public, offering them a mirror to their own lives and times.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

William Powell Frith was born on January 9, 1819, in Aldfield, near Ripon in Yorkshire. His father, Thomas Frith, served as the house steward at Studley Royal, a grand estate, while his mother, Jane (née Powell), came from a family with a longer, though somewhat faded, lineage. Recognizing his son's artistic inclinations early on, Thomas Frith, despite his own more practical background, supported William's ambition to become a painter. This support was crucial in enabling the young Frith to pursue formal art training, a path not always easily accessible.

In 1835, at the age of sixteen, Frith moved to London to begin his artistic education. He first attended Henry Sass's Academy in Bloomsbury, a well-regarded preparatory school for aspiring artists aiming for the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Sass's provided foundational training in drawing, particularly from plaster casts of classical sculptures, instilling a discipline of observation and draughtsmanship that would underpin Frith's later detailed style. His diligence paid off, and in 1837, he successfully gained admission to the Royal Academy Schools.

At the Royal Academy, Frith further honed his skills, studying alongside other talented young artists. The curriculum emphasized drawing from the antique and the life model, as well as anatomy and perspective. During these formative years, Frith initially focused on portraiture, a reliable genre for securing commissions and establishing a reputation. He also began exploring literary and historical subjects, often drawing inspiration from popular authors like Laurence Sterne and Sir Walter Scott, reflecting a common trend among aspiring artists of the period.

The Clique and Early Career Trajectory

While studying at the Royal Academy, Frith became a central figure in an informal group of young artists known as "The Clique." Formed around 1837, this group included Richard Dadd, Augustus Egg, Henry Nelson O'Neil, John Phillip, and Edward Matthew Ward. They shared a dissatisfaction with the perceived conservatism and elitism of the Royal Academy's establishment and its emphasis on "High Art." Instead, The Clique championed genre painting and subjects drawn from literature and everyday life, looking back to earlier British artists like William Hogarth and Sir David Wilkie for inspiration in narrative clarity and social observation.

The Clique met regularly to critique each other's work and discuss artistic ideas. They rejected the idealized, often formulaic approach favoured by the Academy's older generation, seeking instead a more direct engagement with relatable human stories and contemporary themes. Although the group eventually dissolved – partly due to Richard Dadd's tragic descent into madness and subsequent confinement after murdering his father in 1843 – its influence on Frith's development was significant. It reinforced his inclination towards narrative painting and encouraged his focus on subjects with popular appeal.

Frith began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1840. His early submissions included portraits and literary subjects, such as 'Malvolio, cross-gartered, before the Countess Olivia' (1840), based on Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, and scenes inspired by Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. These works demonstrated his growing technical proficiency and narrative skill. His talent was recognized relatively early; he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1845, a significant step in establishing his professional standing within the London art world. This early success laid the groundwork for his later, more ambitious projects.

Rise to Fame: Panoramic Narratives of Modern Life

Frith's breakthrough into widespread public acclaim came with a series of large, complex paintings depicting scenes of contemporary Victorian life. These works marked a decisive shift away from purely literary or historical subjects towards the direct observation and representation of the world around him. He became a master of the panoramic genre scene, orchestrating dozens, sometimes hundreds, of figures into intricate, multi-layered narratives that captured the energy and diversity of modern society.

'Life at the Seaside' (Ramsgate Sands)

Painted between 1851 and 1854, 'Life at the Seaside', more commonly known as 'Ramsgate Sands', was Frith's first major triumph in this new vein. The painting depicts the bustling beach at Ramsgate, a popular Kentish seaside resort accessible by the recently expanded railway network. It presents a cross-section of Victorian society enjoying a day out: families paddling, children digging in the sand, entertainers performing, vendors selling their wares, and elegantly dressed ladies promenading. The detail is meticulous, capturing costumes, activities, and social interactions with remarkable clarity.

The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854 and proved immensely popular with the public. Its appeal lay in its familiarity and its vibrant depiction of a shared contemporary experience – the seaside holiday, a relatively new phenomenon for the expanding middle classes. Queen Victoria herself was charmed by the painting and purchased it for the Royal Collection, a significant endorsement that cemented Frith's reputation. Despite some critics finding the subject matter 'vulgar' or lacking in serious artistic merit due to its everyday theme and inclusion of figures potentially identifiable as lower class or even 'demi-mondaine', the public adored its realism and lively detail. It was successfully engraved, further spreading Frith's fame.

'The Derby Day'

Building on the success of 'Ramsgate Sands', Frith embarked on an even more ambitious project: 'The Derby Day'. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, this painting depicts the Epsom Derby, one of the great social spectacles of the Victorian calendar, attracting vast crowds from every stratum of society. Frith spent nearly two years working on the enormous canvas, meticulously researching the event, making numerous preparatory sketches, and even employing photographers to capture details of the crowd and setting.

'The Derby Day' is a sprawling panorama teeming with life and incident. It presents a microcosm of Victorian England: aristocrats in their carriages, gamblers and touts, acrobats and entertainers, pickpockets, families enjoying picnics, soldiers, clergymen, and country folk. Frith masterfully weaves together numerous small narratives within the larger scene, hinting at stories of fortune won and lost, social aspiration, deception, and simple enjoyment. The painting is a tour de force of observation and composition, capturing the chaotic energy, social diversity, and underlying tensions of the event.

The painting caused an unprecedented sensation when exhibited. Crowds thronged to see it, fascinated by its detail and the recognizability of the social types depicted. The crush of viewers was so great that the Royal Academy, for the first time in its history, had to install a protective railing in front of the painting. Critical reception was largely positive, praising Frith's technical skill and observational powers, though some, like the influential critic John Ruskin, expressed reservations about its moral tone and perceived lack of higher purpose, criticizing its focus on the less savoury aspects of modern entertainment. Nevertheless, 'The Derby Day' became one of the most famous images of the Victorian era, widely reproduced and solidifying Frith's position as the preeminent painter of modern life.

'The Railway Station'

Following the triumph of 'Derby Day', Frith turned his attention to another defining feature of modern Victorian life: the railway. Commissioned by the art dealer Louis Victor Flatow for a substantial sum, 'The Railway Station' (1862) depicts the platform at Paddington Station, London, capturing the moment of departure for a Great Western Railway train. Like his previous panoramas, it is a complex composition filled with diverse figures and multiple narratives, reflecting the impact of rail travel on society.

The painting showcases the technological marvel of the steam engine and the bustling activity of a major terminus. Passengers say their farewells, porters handle luggage, families embark on journeys, and officials oversee the proceedings. Frith included portraits of his own family and friends among the crowd, adding a personal touch. A particularly notable vignette shows two detectives arresting a man on the right side of the platform, adding an element of drama and social commentary, possibly inspired by contemporary news stories or the detective fiction gaining popularity at the time.

Exhibited independently rather than at the Royal Academy, 'The Railway Station' drew huge crowds willing to pay an entrance fee, further demonstrating Frith's immense public appeal. It captured the dynamism, efficiency, and social mixing facilitated by the railway network, a symbol of Victorian progress and modernity. The meticulous rendering of the station architecture, the train itself, and the varied human interactions cemented Frith's reputation as the foremost visual chronicler of his age. These three major works – 'Ramsgate Sands', 'Derby Day', and 'The Railway Station' – established Frith's signature style and thematic concerns.

Artistic Style and Technique

Frith's artistic style is characterized by a commitment to realism, meticulous attention to detail, and complex narrative composition. He worked firmly within the tradition of British genre painting, but elevated it to an unprecedented scale and complexity in his depictions of contemporary life. His technique was grounded in the academic training he received, emphasizing strong draughtsmanship and careful finish.

Detail was paramount in Frith's work. He invested enormous effort in ensuring the accuracy of settings, costumes, and physiognomies. For his large panoramas, he made numerous preparatory sketches and studies of individual figures and groups, often working from life models. He was also an early adopter of photography as an aid, using photographic references to capture architectural details, crowd formations, and fleeting moments, although he always synthesized these elements through his own artistic vision rather than simply copying.

His compositions are typically panoramic and frieze-like, allowing the viewer's eye to travel across the canvas and discover multiple points of interest. He skillfully arranged large numbers of figures to create a sense of bustling activity while maintaining overall coherence. Figures are often grouped into small narrative clusters, inviting the viewer to piece together the implied stories. This episodic structure, akin to chapters in a novel, contributed significantly to the paintings' popular appeal.

Frith's use of colour was generally bright and clear, enhancing the legibility of his detailed scenes. His finish was smooth and polished, leaving little evidence of brushwork, in line with academic conventions of the time. While not an innovator in terms of painterly technique in the way contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner or later the Impressionists were, his technical mastery in handling complex compositions and rendering detail was widely acknowledged, even by those who questioned the artistic merit of his chosen subjects.

Themes and Social Commentary

The primary theme running through Frith's major works is the depiction of modern Victorian society in all its diversity and complexity. He was fascinated by crowds and public spaces – beaches, racecourses, railway stations, art galleries – where different social classes inevitably mingled, interacted, and sometimes clashed. His paintings serve as invaluable documents of Victorian social customs, leisure activities, fashion, and class distinctions.

While often celebratory of the vibrancy of modern life, Frith's work frequently contains elements of social commentary and moral observation, echoing the tradition of Hogarth. In 'Derby Day', for instance, the presence of gamblers, touts, and potential victims hints at the darker side of popular entertainment and the perils of speculation. The arrest scene in 'The Railway Station' introduces a note of crime and justice into the depiction of modern travel.

Later in his career, Frith tackled moral themes more explicitly in narrative series like 'The Road to Ruin' (1878) and 'The Race for Wealth' (1880). These multi-part works traced the downfall of individuals through gambling and financial speculation, respectively, offering cautionary tales in the Hogarthian mould. While popular, these series were generally considered less artistically successful than his earlier, more nuanced depictions of contemporary life.

Frith's focus on the everyday and the contemporary placed him somewhat at odds with the high-minded ideals promoted by influential critics like John Ruskin, who favoured art with a more overt spiritual or didactic purpose, often rooted in nature or historical subjects. Frith, however, believed strongly in the value of depicting the world as he saw it, arguing that modern life was a valid and important subject for art. His immense popularity suggests that the public largely agreed with him.

Literary and Historical Subjects

Although best known for his scenes of contemporary life, Frith did not entirely abandon literary and historical subjects throughout his career. His early success was built partly on paintings inspired by authors like Shakespeare, Goldsmith, Sterne, and Molière. He continued to produce such works periodically, often finding favour with collectors who preferred more traditional themes.

He provided illustrations for editions of Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy and A Sentimental Journey, demonstrating his affinity for 18th-century literature and humour. He also painted scenes from the life of historical figures and fictional characters, such as 'Dolly Varden' (from Dickens's Barnaby Rudge), which proved particularly popular and was widely reproduced. His connection with Charles Dickens was strong; Frith painted the author's portrait and drew inspiration from his vivid characters and social observation.

However, these literary and historical works generally lack the scale, complexity, and immediate social relevance of his major modern-life panoramas. While technically accomplished, they did not capture the public imagination in the same way as 'Derby Day' or 'The Railway Station'. Frith's unique contribution to British art lies firmly in his pioneering role as a painter of the contemporary social scene.

Later Career and Moralizing Tendencies

In the later decades of his career, Frith's focus shifted somewhat. While he continued to paint portraits and genre scenes, he increasingly turned towards works with explicit moral messages, perhaps influenced by the prevailing Victorian taste for didactic art or a desire to counter criticisms of his earlier work's perceived lack of seriousness.

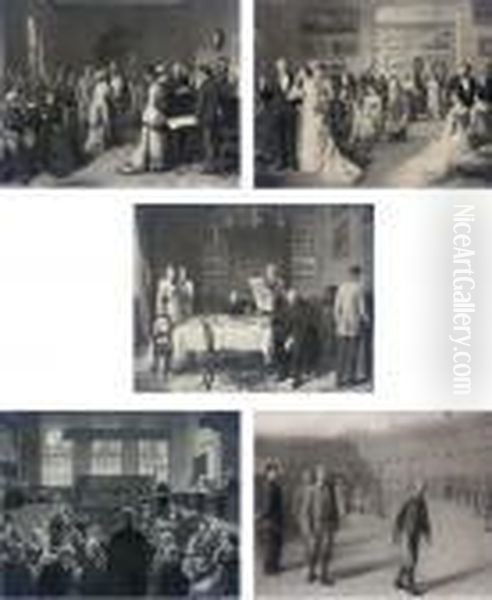

The series 'The Road to Ruin' (1878), comprising five paintings, charts the decline and fall of a young man due to gambling debts, culminating in his suicide. Similarly, 'The Race for Wealth' (1880), another five-part series, depicts the fraudulent activities and eventual downfall of a crooked financier, reflecting contemporary anxieties about financial speculation and commercial morality. These works were conceived in the narrative tradition of Hogarth's 'A Rake's Progress' and 'Marriage A-la-Mode'.

While these series attracted public attention and were exhibited widely, they were generally seen by critics as less successful artistically than his earlier panoramas. The storytelling felt more staged and melodramatic, lacking the spontaneous observation and nuanced social commentary of works like 'Derby Day'. Nevertheless, they demonstrate Frith's continued engagement with the social issues and moral concerns of his time.

'A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881'

One of Frith's most notable later works returned to the theme of contemporary social spectacle: 'A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881' (completed 1883). This painting depicts the fashionable crowd attending the preview day of the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition. It is a fascinating document of the late Victorian art world and London society, featuring portraits of numerous prominent figures, including fellow artists like Sir Frederic Leighton and John Everett Millais, writers like Anthony Trollope, and society figures.

Intriguingly, the painting also includes a group of figures associated with the Aesthetic Movement, notably Oscar Wilde, who is shown expounding to a group of admirers. Frith himself was deeply critical of the Aesthetic Movement and other avant-garde trends, viewing them as departures from truthful representation. His inclusion of Wilde and his circle has been interpreted as satirical, contrasting the perceived affectations of the Aesthetes with the more robust, 'manly' character of traditionalists like Trollope (who stands with his back turned to Wilde's group). Wilde himself famously quipped about the painting, highlighting its celebrity focus.

'A Private View' demonstrates Frith's continued skill in handling complex group compositions and capturing social dynamics. However, like his moralizing series, it perhaps lacks the sheer energy and breadth of social representation found in his earlier masterpieces. It reflects a more specific, perhaps more cynical, view of a particular segment of society.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Throughout his long career, Frith interacted with many of the leading figures in the Victorian art and literary worlds. His early association with The Clique (Dadd, Egg, O'Neil, Phillip, Ward) was formative. His friendship with Augustus Egg remained strong, and they shared an interest in narrative painting.

His relationship with Charles Dickens was particularly significant. The two men were friends, and Frith painted Dickens's portrait in 1859. They shared a keen eye for social detail and character types, and Frith acknowledged Dickens's influence on his approach to depicting the breadth of London life. Frith even participated in amateur theatricals organized by Dickens.

Frith was a prominent member of the Royal Academy for decades (elected RA in 1853) and knew most of the leading artists of his time, including Sir Edwin Landseer, Daniel Maclise, Sir Frederic Leighton, Sir John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. While friendly with many fellow Academicians, he held strong, often critical, views about artistic trends he disliked.

He was particularly opposed to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (Millais, Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti) in its early, more radical phase, finding their detailed style and medievalizing subjects unnatural. Later, he became a vocal critic of the Aesthetic Movement, targeting figures like James McNeill Whistler and Oscar Wilde in his writings and, arguably, in paintings like 'A Private View'. He saw these movements as prioritizing style over substance and departing from the truthful depiction of reality. His relationship with the influential critic John Ruskin was complex; while Ruskin acknowledged Frith's skill, he often lamented the 'low' subject matter and perceived lack of moral elevation in his most popular works. Frith, in turn, could be dismissive of Ruskin's pronouncements. He also collaborated occasionally with illustrators like John Leech.

Views on Art and Conservatism

Frith was fundamentally conservative in his artistic outlook. He believed that the primary duty of the artist was to represent the visible world accurately and engagingly. He valued narrative clarity, technical skill, and subjects that resonated with the experiences and understanding of a broad public. He expressed these views forcefully in his popular memoirs, My Autobiography and Reminiscences (1887) and Further Reminiscences (1888).

In his writings, he vigorously defended his own artistic choices and launched attacks on what he saw as the misguided trends of modern art. He ridiculed the Pre-Raphaelites for their perceived archaism and unnaturalness. He lambasted the Aesthetic Movement for its emphasis on "art for art's sake," its decorative tendencies, and its detachment from everyday life. He was particularly scathing about Impressionism, which was beginning to gain attention in Britain towards the end of his career, dismissing its practitioners as lacking basic drawing skills and producing incomprehensible daubs.

Frith's conservatism extended to his view of the Royal Academy, which he defended against calls for reform, seeing it as a vital institution for upholding artistic standards. While his resistance to new artistic movements might seem reactionary today, it stemmed from a deeply held conviction about the purpose and practice of art, rooted in the traditions of British narrative painting and academic training. His views reflected those of a significant portion of the Victorian art establishment and public.

Personal Life

Frith's personal life was more complex than his public image as a pillar of the Victorian art world might suggest. He married Isabelle Baker in 1845, and they had twelve children together. However, for many years, Frith maintained a secret second family just a mile away with Mary Alford, his former ward, with whom he had another seven children.

This double life was kept hidden from public view until after Isabelle's death in 1880. Frith then married Mary Alford the following year. The strain and expense of maintaining two large households must have been considerable, perhaps contributing to his focus on producing highly popular and commercially successful paintings. This aspect of his life reveals a significant contrast between the public persona and private reality, a dichotomy not uncommon in the often-hypocritical moral climate of the Victorian era. Despite these complexities, he appears to have been a devoted father to all his children.

Legacy and Collections

William Powell Frith enjoyed enormous success and popularity during his lifetime. His major paintings were public sensations, attracting huge crowds and commanding high prices. His work was widely disseminated through engravings, making his images familiar to a vast audience across Britain and beyond. He was honoured with membership in the Royal Academy and received numerous accolades. For several decades, he was arguably the most famous living painter in Britain.

After his death on November 2, 1909, at the age of 90, his reputation declined significantly. The rise of modernism led to a rejection of Victorian academic painting, and Frith's detailed realism and narrative focus came to be seen as old-fashioned and illustrative rather than truly artistic. Critics dismissed his work as mere social documentation lacking profound aesthetic value.

However, from the mid-20th century onwards, there has been a gradual reassessment of Victorian art, and Frith's work has enjoyed a revival of interest among art historians and the public. His paintings are now recognized not only as invaluable historical documents but also for their technical brilliance, compositional skill, and insightful portrayal of the complexities of Victorian society. He is acknowledged as a master storyteller in paint and a key figure in the history of British genre painting.

His major works are now held in prestigious public collections. 'Derby Day' is in the Tate Britain collection (though often displayed at the National Gallery, London). 'Ramsgate Sands' remains in the Royal Collection. 'The Railway Station' is housed at Royal Holloway, University of London. 'A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881' is a key work in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut. Other paintings can be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Mercer Art Gallery, Harrogate (which holds a significant collection related to him), and numerous other museums in the UK and internationally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Frith's works also continue to perform well on the art market when they appear. A smaller version or study for 'Derby Day' fetched a significant price at Christie's in 2011 (£505,250). A version of 'The Private View' sold for £150,000 at Christie's in 2008. Even lesser-known works like 'The Fortune Teller' command respectable prices, indicating sustained collector interest.

Conclusion: A Mirror to an Age

William Powell Frith remains a fascinating and important figure in British art history. His decision to focus on large-scale depictions of contemporary life set him apart from many of his contemporaries and resulted in some of the most iconic images of the Victorian era. Through works like 'Ramsgate Sands', 'Derby Day', and 'The Railway Station', he held up a mirror to his age, capturing its energy, diversity, social strata, and burgeoning modernity with unparalleled detail and narrative flair.

While his artistic conservatism and resistance to emerging styles may have dated his reputation in the early 20th century, his work is now appreciated for its unique qualities: its masterful handling of complex compositions, its keen observation of human behaviour, and its invaluable role as a visual record of Victorian society. He was a superb technician and a compelling storyteller whose paintings continue to engage and inform viewers today. More than just a painter, William Powell Frith was a visual historian, the great chronicler in paint of the vibrant, multifaceted world of Victorian Britain.