Francesco Fracanzano (1612-1656) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th-century Naples. A painter whose life was as dramatic as some of his canvases, Fracanzano navigated the powerful currents of Caravaggism, the influence of his eminent teacher Jusepe de Ribera, and the broader European artistic trends to forge a style marked by robust naturalism, poignant emotional depth, and a distinctive handling of light and shadow. His contributions to the Neapolitan School, though perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, are undeniable, offering a compelling window into the religious fervor, human drama, and artistic innovation of the Baroque era.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Monopoli and Naples

Born in Monopoli, a coastal town in Apulia, Southern Italy, in 1612, Francesco Fracanzano's artistic inclinations were likely nurtured from a young age. His father, Alessandro Fracanzano, was also a painter, suggesting an early immersion in the craft. However, the provincial setting of Monopoli, while perhaps providing foundational training, could not offer the artistic stimulation and opportunities available in a major cultural hub. Like many ambitious artists of his time, Francesco, along with his brother Cesare Fracanzano, who also pursued a career as a painter, made the pivotal decision to relocate to Naples.

Naples in the early 17th century was a bustling metropolis, the largest city in Italy and a vital center of the Spanish Empire. It was a crucible of artistic activity, profoundly shaped by the revolutionary naturalism of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, who had worked there briefly but left an indelible mark. The city's artistic scene was dominated by powerful personalities and distinctive stylistic trends. It was into this dynamic environment that the Fracanzano brothers arrived, eager to hone their skills and make their mark.

Under the Shadow of "Lo Spagnoletto": Apprenticeship with Jusepe de Ribera

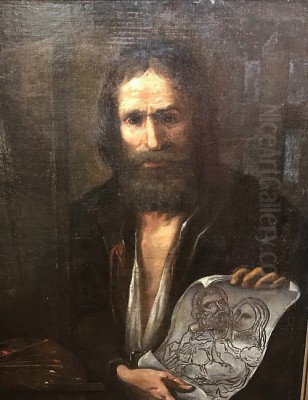

The most significant step in Francesco Fracanzano's artistic development was his entry into the workshop of Jusepe de Ribera. Known as "Lo Spagnoletto" (the Little Spaniard) due to his Spanish origins and small stature, Ribera was a towering figure in Neapolitan art. Having absorbed the lessons of Caravaggio, Ribera developed a powerful, often gritty, realism, characterized by dramatic tenebrism (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark), meticulous attention to anatomical detail, and an unflinching portrayal of human suffering and spiritual intensity.

Working in Ribera's studio, Francesco Fracanzano was immersed in this potent artistic language. He would have learned to master the techniques of chiaroscuro, to model forms with a palpable sense of volume, and to capture the raw emotion in his subjects. Ribera's influence is evident in Fracanzano's early works, which often feature half-length figures of saints, philosophers, or common folk, rendered with a similar intensity and tactile quality. The depiction of aged, weathered skin, a hallmark of Ribera, also appears in Fracanzano's portrayals. His brother Cesare, too, absorbed these lessons, and the two brothers often worked in a closely related style during their formative years.

Evolving Style: Naturalism, Classicism, and External Influences

While Ribera's impact was foundational, Francesco Fracanzano's artistic personality was not merely a reflection of his master. As he matured, his style evolved, incorporating a broader range of influences. The initial, somewhat stark naturalism inherited from Ribera began to soften, infused with a greater sense of painterly richness and, at times, a more classical composure.

Sources suggest that Fracanzano was receptive to the artistic currents flowing into Naples from other Italian centers and beyond. The influence of Venetian painting, particularly the rich colorism and looser brushwork associated with artists like Titian and Tintoretto, can be discerned in some of his works, lending a warmth and vibrancy to his palette. There are also indications that he absorbed elements from the Bolognese school, perhaps through artists like Guido Reni or Domenichino, whose more idealized and classical forms offered an alternative to the raw naturalism of the Caravaggisti.

Furthermore, the elegant and refined style of Flemish master Anthony van Dyck, who had a profound impact on Italian art, particularly in Genoa and Sicily, may also have filtered into Fracanzano's consciousness. This could account for a certain grace or sophistication in the rendering of drapery or in the portrayal of some figures, tempering the more rugged aspects of his Riberesque training. Fracanzano's ability to synthesize these diverse influences—the dramatic naturalism of Ribera, the chromatic richness of the Venetians, the classical tendencies of the Bolognese, and the elegance of Van Dyck—while retaining a core commitment to Roman classicism's taste, speaks to his artistic intelligence and adaptability.

His works became known for their vivid characterizations, with figures displaying a wide range of human emotions, from profound piety and ecstatic devotion to quiet contemplation and earthly suffering. He excelled in capturing the individuality of his subjects, whether they were venerable saints, anonymous figures, or characters from mythological or philosophical narratives. His naturalism was not merely superficial; it extended to a deep understanding of human psychology, conveyed through expressive faces and gestures.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Francesco Fracanzano's oeuvre primarily consists of religious and philosophical subjects, common themes in Baroque art, which was heavily patronized by the Church and private collectors seeking morally edifying or intellectually stimulating works.

Among his most celebrated paintings are those executed for the church of San Gregorio Armeno in Naples. These include "The Saint thrown into the well" (often identified as Saint Gregory the Illuminator) and "The Miracle of Saint Gregorio." These large-scale compositions demonstrate his ability to handle complex narratives with dramatic flair, employing dynamic compositions and expressive figures to engage the viewer. The interplay of light and shadow in these works effectively heightens the emotional tension and focuses attention on the key moments of the story.

Another masterpiece often attributed to Fracanzano is "The Death of Saint Joseph," located in the church of the Pellegrini Hospital (Ospedale dei Pellegrini) in Naples. This work is praised for its tender portrayal of the dying saint, surrounded by Christ and the Virgin Mary. The painting showcases Fracanzano's skill in conveying profound emotion through subtle gestures and expressions, as well as his mastery of chiaroscuro to create a solemn and intimate atmosphere. The humanity of the figures, even in a sacred scene, is a hallmark of his approach.

Fracanzano also painted numerous half-length figures of saints and philosophers, a genre popularized by Ribera. These works allowed him to focus on individual characterization and psychological depth. "The Penitence of St Peter," a version of which was discovered in Dubrovnik, is a powerful example, depicting the apostle's remorse with palpable intensity. His portrayals of figures like Saint Paul also capture a sense of gravitas and intellectual force.

Beyond explicitly religious subjects, Fracanzano also explored genre-like figures, sometimes with a philosophical undertone. The "Head of an old goitred woman," once in the Federico Zeri collection, is a striking example of his unflinching realism, capturing the physical peculiarities of the subject with a directness that is both arresting and empathetic. Such works blur the line between portraiture and character study, reflecting the Baroque fascination with diverse human types.

A work titled "Roman Triumph," mentioned with a problematic early date, likely refers to a composition demonstrating his engagement with classical themes, a common interest for artists of the period who looked to antiquity for inspiration in terms of subject matter and formal ideals. Similarly, drawings like "Studies of Three Heads: A Woman, a Satyress, and a Youth" (though its dating is also problematic if post-1656) would highlight his skill as a draftsman and his interest in capturing varied physiognomies and expressions, a fundamental practice for Baroque artists.

Interactions with Contemporaries: A Neapolitan Network

Francesco Fracanzano was an active participant in the Neapolitan art world, and his career was intertwined with those of several other notable painters. His closest artistic bond was, of course, with his brother, Cesare Fracanzano, with whom he shared his early training and likely collaborated on occasion.

His relationship with Jusepe de Ribera was that of a student to a master, and Ribera's workshop was a hub for many aspiring painters. The influence was profound and lasting, shaping Fracanzano's fundamental approach to painting.

A particularly significant connection was with Salvator Rosa (1615-1673), one of the most original and independent artistic personalities of the 17th century. Rosa, known for his wild landscapes, battle scenes, and philosophical allegories, was Francesco Fracanzano's brother-in-law, having married Fracanzano's sister. Early in his career, Rosa spent time in Fracanzano's workshop, and it is believed that Fracanzano played a role in his artistic formation, particularly in grounding him in the naturalistic tradition of Naples. While Rosa would later develop a highly individual style, this early exposure to Fracanzano's Riberesque naturalism was an important formative experience.

Fracanzano also moved within the broader circle of Neapolitan painters. This included artists like Aniello Falcone (1607-1656), a renowned painter of battle scenes, with whom Fracanzano likely had professional contact. The Neapolitan school of this period was rich and diverse, featuring prominent figures such as Massimo Stanzione (c. 1585-1656), who blended Caravaggist naturalism with a more classical elegance, often seen as a rival to Ribera. Other notable contemporaries whose work contributed to the city's artistic vibrancy included Bernardo Cavallino (1616-1656), known for his small-scale, exquisitely painted biblical and mythological scenes, and Andrea Vaccaro (1604-1670), whose prolific output often synthesized elements from Caravaggio, Reni, and Van Dyck.

Later in the century, artists like Mattia Preti (1613-1699), though arriving in Naples after Fracanzano's peak, would further develop the dramatic potential of Neapolitan Baroque. The artistic environment was one of intense competition but also of shared influences and stylistic dialogues. Fracanzano's position within this network was that of a respected practitioner who, while perhaps not reaching the international fame of Ribera or the idiosyncratic brilliance of Rosa, made substantial contributions to the city's artistic patrimony. His engagement with the legacy of Caravaggio was, like most Neapolitan painters of his generation, indirect but pervasive, filtered through the interpretations of artists like Ribera and Battistello Caracciolo.

A Life Marred by Turmoil: Personal Tragedy and Untimely End

Francesco Fracanzano's artistic career, though productive, was overshadowed by a turbulent personal life that ultimately led to a tragic end. Historical accounts, notably those by the art historian Bernardo De Dominici (whose reliability is sometimes questioned but who remains a key source for Neapolitan artists), paint a picture of a man whose passions could lead to extreme actions.

He was married, but the union was reportedly unhappy. De Dominici recounts that Fracanzano's wife, Giovanna (possibly Salvator Rosa's sister, though this detail varies in sources), was unfaithful. Consumed by jealousy and rage, or perhaps, as some sources suggest, incited by his wife to commit a serious crime for other motives, Fracanzano found himself on the wrong side of the law. The exact nature of his transgression is not always clearly specified, but it was severe enough to warrant a death sentence.

In 1656 (some sources cite 1657, but 1656 is more commonly accepted), at the height of his artistic powers and still relatively young at the age of 44, Francesco Fracanzano was executed, reportedly by poisoning. This grim end cut short a promising career and added a layer of dark romance to his biography. The plague that ravaged Naples in 1656 also claimed the lives of many other artists, including Bernardo Cavallino and Aniello Falcone, decimating a generation of talent, but Fracanzano's death was a direct result of human justice, however harsh.

The difficult circumstances of his family, with his father dying relatively early and his mother facing poverty, may also have contributed to a life lived under pressure, though this is speculative. What is clear is that his personal life was far from serene, a stark contrast to the spiritual depth he often conveyed in his paintings.

Art Historical Evaluation, Controversies, and Legacy

In the annals of art history, Francesco Fracanzano has occupied a somewhat ambiguous position. For a long time, he was primarily seen as a follower of Ribera, a talented but ultimately secondary figure. His works were sometimes confused with those of his master or other Neapolitan painters. However, modern scholarship has increasingly sought to define his individual artistic personality and to re-evaluate his contributions.

One area of ongoing discussion and occasional controversy revolves around attributions. The stylistic similarities between Fracanzano, his brother Cesare, Ribera, and other artists in their circle can make definitive attributions challenging, especially for works that are not documented. Some scholars have pointed to a more "free and spirited" manner in certain paintings, suggesting a departure from the tighter handling often associated with Ribera, as a characteristic of Fracanzano's independent style. The debate over the authorship of works like the "Transito di S. Giuseppe" (Death of St. Joseph) highlights these complexities.

Critiques of Fracanzano's work have sometimes centered on a perceived lack of groundbreaking innovation. While he masterfully assimilated and synthesized various influences, he is not generally seen as an artist who radically altered the course of art history in the way that Caravaggio or even Ribera did. His art, while powerful and expressive, largely operated within the established parameters of Neapolitan Baroque naturalism, enriched by his personal sensibility. Some have argued that his artistic vision, while potent, did not fully transcend the local Neapolitan context to achieve a more universal impact.

Despite these critiques, Fracanzano's importance within the Neapolitan school is increasingly recognized. His ability to convey intense emotion, his robust modeling of form, and his skillful use of light and color mark him as a significant talent. His works embody the dramatic and often visceral piety of Counter-Reformation Naples, and his figures, whether saints or sinners, possess a compelling human presence.

His influence on Salvator Rosa, even if limited to Rosa's early years, is also a noteworthy aspect of his legacy. By transmitting the Riberesque tradition to such an original talent, Fracanzano played a part in the broader dissemination and transformation of Neapolitan artistic ideas.

The tragic circumstances of his death have perhaps, at times, overshadowed a more nuanced appreciation of his artistic achievements. However, as art historical research continues to shed light on the complexities of the Neapolitan Seicento, Francesco Fracanzano emerges as a painter of considerable skill and emotional depth, a vital contributor to one of the most exciting chapters in Italian art history. His paintings, found in churches and museums primarily in Naples but also in collections elsewhere, continue to resonate with their powerful blend of naturalism, drama, and spiritual intensity. He remains a testament to the rich artistic fabric of Baroque Naples, a city that fostered both immense talent and profound human drama. His legacy is that of an artist who, despite a life cut tragically short, left behind a body of work that speaks eloquently of the passions, faith, and artistic fervor of his time.