Lucien Whiting Powell (1846–1930) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in American art history, celebrated particularly for his evocative and atmospheric depictions of iconic landscapes, most notably the ethereal canals of Venice and the majestic vistas of the Grand Canyon. Born into an era of profound national change and artistic evolution, Powell's career bridged the romantic sensibilities of the 19th century with the burgeoning modernism of the early 20th. His work, deeply influenced by the British master J.M.W. Turner, showcases a remarkable ability to capture light, mood, and the sublime power of nature.

Early Life and the Call to Art

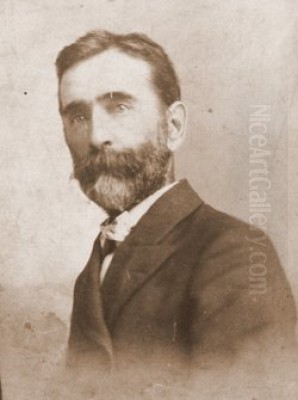

Lucien Whiting Powell was born on December 13, 1846, at Levinworth Manor in Upperville, Fauquier County, Virginia. He hailed from a distinguished and aristocratic Southern family, a background that afforded him access to education and culture from a young age. His early schooling was received in local district schools, supplemented by instruction from private tutors, a common practice for families of means in the antebellum South.

The outbreak of the American Civil War dramatically interrupted his youth. Powell, loyal to his Virginian roots, enlisted in the Confederate army, serving with the renowned 11th Virginia Cavalry. The rigors and trauma of war took a toll on his health. Upon returning home after the conflict, his physical condition was notably compromised. It was reportedly his mother who, observing his weakened state and perhaps a nascent artistic inclination, suggested that he pursue painting as a less physically demanding and more restorative livelihood. This pivotal suggestion set Powell on a path that would define the remainder of his life.

Following the war and this maternal guidance, Powell relocated to Philadelphia, a city then burgeoning as an artistic and cultural center in the United States. It was here that he began his formal artistic training, a crucial step in honing his natural talents.

Artistic Formation: Moran, Turner, and European Sojourns

In Philadelphia, Powell had the distinct advantage of studying under Thomas Moran (1837–1926), one of America's preeminent landscape painters. Moran, himself heavily influenced by J.M.W. Turner, was a leading figure associated with the later generation of the Hudson River School and was renowned for his dramatic portrayals of the American West, particularly Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. Studying with Moran would have exposed Powell to a tradition that emphasized both detailed observation of nature and a romantic, often grandiose, interpretation of its splendors. Moran's own vibrant palette and his mastery of light and atmospheric effects undoubtedly left a lasting impression on his student.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and immerse himself in the European tradition, Powell traveled to London in 1875. He enrolled in the London School of Art, further refining his technical skills. Perhaps more significantly, he dedicated considerable time to studying and copying the works of Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) at the National Gallery. Turner, the great English Romantic painter, was legendary for his expressive color, dynamic compositions, and his unparalleled ability to depict the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere. For an aspiring landscape painter like Powell, direct engagement with Turner's masterpieces was an invaluable experience, shaping his aesthetic vision and technical approach. The influence of Turner's luminous, often dreamlike, style would become a hallmark of Powell's mature work, particularly in his Venetian scenes.

Powell's European experiences were not limited to this initial visit. He returned to Europe in 1890, a trip during which he focused extensively on capturing the unique beauty of Venice. His Venetian paintings from this period are often described as "dreamlike," imbued with a soft, hazy light and a romantic sensibility that clearly echoes Turner's own famous depictions of the city. These works cemented his reputation as a painter capable of translating the poetic essence of a place onto canvas.

The American West: Confronting the Sublime

While Europe, and Venice in particular, offered Powell rich artistic inspiration, he also turned his gaze to the monumental landscapes of his own continent. In 1901, he embarked on a significant sketching and painting expedition to the American West, specifically to the Grand Canyon in Arizona. This journey placed him in the company of other notable artists like his mentor Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), who had earlier revealed the awe-inspiring scale and beauty of the West to the American public.

Powell's encounters with the Grand Canyon resulted in some of his most famous and impactful works. He sought to convey not just the geological grandeur of the canyon but also its shifting moods, the play of light and shadow across its vast expanses, and the almost spiritual sense of immensity it evoked. His painting titled "The Grand Canyon" became particularly well-known, showcasing his ability to handle a subject of such overwhelming scale with both accuracy and artistic sensitivity. Another notable work, "Twilight, Grand Canyon," exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1906, further demonstrated his skill in capturing the subtle atmospheric effects and color transitions of the desert landscape at dusk. These Western paintings contributed significantly to his acclaim in the United States.

Further Travels and Diverse Subjects

Powell's artistic curiosity extended beyond Europe and the American West. His travels also took him to the Middle East, including the Holy Land. Around 1910, he undertook a journey that included sketching in Palestine, seeking to capture the historic and spiritual resonance of these ancient landscapes. While the provided information mentions "St. Iago" in the context of the Middle East, this might be a slight confusion, as Santiago de Compostela is in Spain. However, his travels to the Holy Land are documented, adding another dimension to his oeuvre, reflecting a common 19th-century artistic interest in biblical and historical sites, a path also trodden by artists like Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) in his depictions of Jerusalem and the Parthenon.

His earlier works, before his extensive travels, often reflected his Virginian heritage. He painted scenes of life in his home state, including nocturnal depictions of rural settings, such as barn interiors. These pieces, possibly developed from sketches made before or immediately after the Civil War (between 1868 and 1875), show an early interest in the effects of light and shadow, albeit on a more intimate scale than his later grand landscapes.

Powell's Artistic Style: A Lyrical Romanticism

Lucien Whiting Powell's artistic style is best characterized as a lyrical form of Romantic Realism, deeply indebted to the atmospheric concerns of J.M.W. Turner and the American landscape tradition. He was not strictly an adherent to any single art movement but rather synthesized various influences into a personal and recognizable aesthetic.

The influence of Turner is paramount. Powell's handling of light – often soft, diffused, and glowing – and his ability to create a sense of atmosphere, whether the humid haze of Venice or the clear, crisp air of the Grand Canyon, are testaments to his study of the British master. Like Turner, Powell was interested in the emotional impact of landscape, striving to convey a sense of wonder, awe, or poetic melancholy. This aligns him with the broader Romantic movement, which emphasized subjectivity, emotion, and the sublime power of nature.

However, Powell's work also retained a strong element of realistic observation, a trait shared with the Hudson River School painters such as Asher B. Durand (1796-1886) and John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872), and his teacher Thomas Moran. His landscapes, while often idealized or romanticized in their mood, were grounded in careful study of the actual locations. He possessed a profound understanding of natural forms, geological structures, and the way light interacts with different surfaces.

His Venetian scenes are particularly illustrative of his style. They are less about precise architectural rendering and more about capturing the unique interplay of water, light, and architecture that defines Venice. Gondolas glide through shimmering canals, buildings emerge softly from misty backgrounds, and the overall effect is one of serene, dreamlike beauty. These works can be compared to those of other artists captivated by Venice, such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), whose Venetian etchings and nocturnes share a similar concern for atmosphere and tonal harmony, or John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), whose vibrant Venetian watercolors captured the city's dazzling light. Even Félix Ziem (1821-1911), a French painter of the Barbizon school, was immensely popular for his romanticized Venetian scenes, and Powell's work fits within this tradition of foreign artists interpreting the city's allure.

In his Grand Canyon paintings, Powell faced the challenge of conveying immense scale and complex geological formations. Here, his style balanced the grandeur sought by artists like Bierstadt with a more nuanced attention to color and atmospheric perspective. He captured the layered colors of the canyon walls, the deep shadows, and the vast, light-filled skies, creating images that were both topographically recognizable and emotionally resonant.

His palette was often rich and varied, capable of depicting the brilliant hues of a desert sunset or the subtle, pearlescent tones of a misty Venetian morning. His brushwork, while generally controlled, could also be expressive, particularly in passages meant to convey the texture of rock or the shimmer of water. He was a master of composition, skillfully leading the viewer's eye through his landscapes and creating a harmonious balance of elements.

While not directly associated with Luminism, a mid-19th century American landscape style characterized by its meticulous rendering of light and atmosphere as seen in the works of Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) or Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Powell's keen sensitivity to light effects certainly shares some affinities with this movement. Similarly, while distinct from the more introspective and moody works of Tonalist painters like George Inness (1825–1894) or Dwight William Tryon (1849-1925), Powell's emphasis on mood and atmosphere in his Venetian pieces sometimes approached a Tonalist sensibility.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be extensive, several key works and types of works define Powell's contribution:

Venetian Scenes: These are perhaps his most iconic and sought-after pieces. Characterized by their soft focus, luminous atmosphere, and romantic mood, they often depict classic Venetian motifs: gondolas on the Grand Canal, views of Santa Maria della Salute, or quiet side canals. The influence of Turner is most palpable here, with an emphasis on light reflecting off water and suffusing the air.

"The Grand Canyon" (and related works): His depictions of this natural wonder showcase his ability to handle subjects of immense scale and dramatic impact. These paintings are notable for their rich color, detailed rendering of geological formations, and the successful conveyance of the canyon's depth and vastness. "Twilight, Grand Canyon" specifically highlights his skill with atmospheric effects and the subtle colors of dusk.

Holy Land Landscapes: These works, stemming from his travels around 1910, would have appealed to a 19th and early 20th-century audience interested in biblical history and exotic locales. They likely combined topographical accuracy with a sense of reverence appropriate to the subject matter.

Early Virginian Scenes: Paintings such as nocturnal barn interiors from the period 1868-1875 demonstrate his early development and interest in light effects even before his extensive European training. These offer a glimpse into his formative years and regional focus.

His body of work consistently demonstrates a dedication to capturing the essence of a place, not merely its physical appearance, but its emotional and atmospheric qualities.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Collections

Lucien Whiting Powell achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, with his works being featured in numerous prominent exhibitions. His participation in these shows indicates his standing within the American art community and provided platforms for his work to be seen by a wider public.

He exhibited at:

The Louisville Industrial Exposition (during the 1870s), an early venue for showcasing his talents.

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, one of the oldest and most prestigious art institutions in the United States. His 1906 exhibition of "Twilight, Grand Canyon" here was a significant acknowledgment.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., a major institution that played a vital role in the capital's art scene. (Many of its American art holdings are now with the National Gallery of Art).

The Washington D.C. Watercolor Club, indicating his proficiency in this medium as well.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (though this might refer to later acquisitions or exhibitions after its founding, or confusion with the National Gallery in London where he studied Turner).

Powell's paintings found their way into important public and private collections, a testament to their appeal and artistic merit. Today, his works are held by:

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (which absorbed much of the Corcoran's collection).

The Kokomo Art Museum (Indiana).

The High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia.

The Johnson Collection in Spartanburg, South Carolina, which focuses on Southern art.

The Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia, the first museum dedicated to the art and artists of the American South.

His works also appear in commercial galleries such as the Bedford Fine Art Gallery, indicating a continued market interest.

The inclusion of his work in exhibition catalogues like "Back to Black: Art, Cinema, and the Racial Imaginary" (2005) and "To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities" (1999) is particularly interesting. It suggests that his art may be present in HBCU collections or is considered relevant in broader discussions of American art that intersect with diverse cultural narratives, perhaps due to his Southern origins or the universal appeal of his landscapes.

The Enigma of Powell's Wealth

An intriguing anecdote surrounds Lucien Whiting Powell's financial affairs. Upon his death in 1930, his estate was reportedly found to contain a surprising $800,000 in cash. This was a substantial sum at the time, especially considering that his annual income from painting sales or salary was never thought to have exceeded $30,000. Furthermore, his federal income tax returns allegedly showed an income of over $200,000 in the last year of his life.

This discrepancy between his known earnings as an artist and the wealth discovered at his death remains something of a mystery. It could suggest astute investments, successful but unpublicized sales, or other financial activities not directly tied to his public artistic persona. Regardless of its origins, this financial success, particularly in his later years, indicates a high level of demand for his work or considerable financial acumen.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Powell worked during a dynamic period in American art. The Hudson River School's dominance was waning, giving way to influences from Europe such as the Barbizon School (which influenced American Tonalists like George Inness and Alexander Helwig Wyant) and Impressionism. Artists like Winslow Homer (1836–1910) were forging a distinctly American Realism, while expatriates like Whistler and Sargent were achieving international fame.

Powell's commitment to a Romantic-Realist landscape style placed him somewhat apart from the avant-garde movements of his later career, yet his work resonated with a public that still appreciated skillful representation and evocative depictions of nature. His contemporaries in American landscape painting included not only his teacher Thomas Moran and figures like Albert Bierstadt, but also artists like Thomas Hill (1829-1908), another painter of the grand vistas of the American West, particularly Yosemite.

In Washington, D.C., where he was active, the Corcoran Gallery of Art was a central institution. While the Washington Color School painters like Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland emerged later, Powell would have been part of an earlier generation of artists contributing to the cultural life of the capital. His adherence to landscape painting provided a continuous thread connecting to earlier American masters like Thomas Cole (1801-1848), the founder of the Hudson River School, even as artistic tastes evolved.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Lucien Whiting Powell passed away on September 27, 1930, at the age of 83 or 84, in Washington, D.C. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its beauty, technical skill, and emotive power. His legacy lies in his ability to synthesize the grand Romantic tradition of Turner with an American sensibility for landscape. He was a master of light and atmosphere, capable of transporting viewers to the sun-drenched canals of Venice or the awe-inspiring depths of the Grand Canyon.

While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or early Modernists, Powell excelled within his chosen idiom. He provided a vital link to the Romantic landscape tradition, keeping its values alive well into the 20th century. His paintings are more than mere topographical records; they are poetic interpretations of nature's majesty and charm, filtered through a sensitive artistic temperament.

His works continue to be valued by collectors and museums, particularly those specializing in American art and art of the American South. The enduring appeal of his paintings lies in their timeless beauty and their power to evoke a sense of wonder and tranquility. Lucien Whiting Powell remains a testament to the enduring power of landscape painting to capture not just the appearance of the world, but also its soul.

Conclusion

Lucien Whiting Powell's journey from a Virginian aristocrat and Civil War soldier to a celebrated painter of international landscapes is a compelling American story. His dedication to his craft, his profound engagement with the art of J.M.W. Turner, and his extensive travels resulted in a body of work that is both diverse and consistently high in quality. Whether depicting the misty romance of Venice, the sublime grandeur of the Grand Canyon, or the historic resonance of the Holy Land, Powell's paintings invite contemplation and admiration. As an artist who skillfully balanced observation with poetic interpretation, he carved out a distinctive niche in the rich tapestry of American art history, leaving a legacy of beautiful and evocative landscapes that continue to enchant viewers today.