Francis Luis Mora stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art. Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1874, and passing away in New York City in 1940, Mora navigated a unique path, bridging the artistic traditions of his Hispanic heritage with the burgeoning modernism of his adopted homeland, the United States. A remarkably versatile talent, he excelled as a painter, muralist, illustrator, etcher, and educator, leaving behind a rich body of work that reflects the cultural complexities and dynamic spirit of his time. His art, characterized by technical proficiency and a keen observational eye, captured everything from the vibrant street life of Spain to the intimate moments of American domesticity and the grand narratives of history and allegory.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

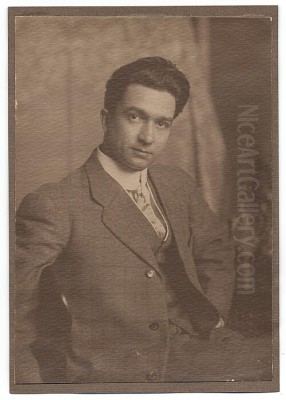

Francis Luis Mora's artistic inclinations were perhaps preordained. He was born into a family deeply immersed in the arts. His father, Domingo Mora, was a respected Spanish sculptor, and his mother, Laura Gaillard, was of French heritage from Uruguay. This multicultural background provided a rich tapestry of influences from a young age. The family emigrated from Uruguay to the United States during Mora's childhood, eventually settling near Boston. This move proved pivotal, placing the young Mora in proximity to a thriving artistic environment.

His formal artistic training began at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. There, he studied under two leading figures of the Boston School of painting, Frank W. Benson and Edmund C. Tarbell. Both Benson and Tarbell were renowned American Impressionists, known for their bright palettes, depictions of genteel life, and emphasis on light and atmosphere. Their instruction undoubtedly provided Mora with a strong foundation in academic draftsmanship and painterly technique, though his own style would evolve distinctively.

Seeking further development, Mora moved to New York City and continued his studies at the prestigious Art Students League. This institution was a crucible of artistic innovation, attracting students and instructors with diverse approaches. Here, Mora would have encountered a wider range of artistic philosophies, likely interacting with students and faculty who were exploring realism, impressionism, and the nascent stirrings of modernism. His time at the League further honed his skills and broadened his artistic horizons, preparing him for a multifaceted career. His brother, Joseph Jacinto "Jo" Mora, also became a notable artist, known for his sculptures, illustrations, and cartography focused on the American West.

The Enduring Influence of Spain

Despite his American training and life, Mora's Hispanic roots remained a powerful and recurring source of inspiration throughout his career. He traveled to Europe, spending significant time in Spain, immersing himself in the land of his father's birth. This experience had a profound impact on his art. He was deeply drawn to the Spanish Old Masters, particularly the work of Diego Velázquez. Mora admired Velázquez's masterful handling of paint, his psychological depth in portraiture, and his ability to capture realism with painterly bravura. Echoes of Velázquez, and perhaps also Francisco Goya, can be seen in Mora's dramatic compositions, his use of rich, often darker tones, and his interest in capturing the essence of Spanish life and culture.

This Spanish influence manifested directly in his subject matter. Mora frequently painted scenes of Spanish fairs, flamenco dancers, bullfights, and romantic historical vignettes. Works like Spanish Fair and After the Bullfight, Granada exemplify this engagement, showcasing vibrant crowds, traditional costumes, and a palpable sense of energy and atmosphere. He wasn't merely documenting; he sought to convey the spirit and emotion of these cultural expressions.

Mora was not alone among American artists of his generation in looking towards Spain. John Singer Sargent, with his dazzling Spanish-themed works, and William Merritt Chase, who also admired Velázquez and taught Spanish painting techniques, were prominent contemporaries who shared this fascination. Robert Henri, a key figure associated with the Ashcan School and a fellow instructor at the Art Students League, also traveled to Spain and encouraged his students to study the Spanish masters. Mora's contribution was unique, however, filtered through his personal heritage and blended with his American sensibilities.

Capturing American Life

While Spain provided a rich vein of subject matter, Francis Luis Mora was equally adept at observing and depicting the world around him in the United States. He turned his skilled brush to capturing the nuances of early 20th-century American life, often focusing on scenes of leisure, domesticity, and social interaction. His paintings frequently feature elegantly dressed figures in interiors, enjoying quiet moments, reading, or engaging in conversation. Works like The Morning News or Color Harmony showcase his ability to handle complex compositions, render textures convincingly, and infuse everyday scenes with a sense of grace and intimacy.

His depictions often focused on the comfortable middle and upper classes, reflecting the world he likely moved in. However, his work sometimes touched upon broader social tapestries. While not formally part of the Ashcan School – the group known for its gritty portrayals of urban working-class life, including artists like John Sloan, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens – Mora shared their interest in contemporary life as a valid subject for art. His approach was generally more refined and less focused on social commentary, but his commitment to observing and rendering the present day connects him to the broader realist trends of the era.

His American scenes often display a brighter palette compared to his Spanish works, perhaps reflecting the influence of his Impressionist teachers Benson and Tarbell, or simply responding to the different quality of light and subject matter. He skillfully balanced detailed rendering with painterly brushwork, creating images that felt both immediate and thoughtfully composed. These works provide valuable visual records of the manners, fashions, and social environments of his time.

Master Illustrator of the Golden Age

Beyond his work as a painter, Francis Luis Mora achieved significant success and recognition as an illustrator. He worked during what is often termed the "Golden Age of American Illustration," a period when magazines and books featured high-quality artwork by exceptionally talented artists. Mora's illustrations graced the pages and covers of prominent publications, including Harper's Weekly, Scribner's, The Century Magazine, Collier's, and Ladies' Home Journal.

His skill as a draftsman, his ability to compose narrative scenes, and his versatility made him highly sought after. He could create dramatic historical illustrations, charming genre scenes, and sophisticated depictions of contemporary life. His work appeared alongside that of other giants of illustration like Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Charles Dana Gibson. This aspect of his career brought his art to a wide public audience, shaping popular visual culture.

During World War I, Mora applied his illustrative talents to the war effort. He created compelling posters for the Red Cross and other organizations, contributing to mobilization and public awareness campaigns. He also designed insignia for the US Navy Committee. This patriotic work further demonstrated his versatility and his engagement with the major events of his time. His success in illustration provided financial stability and complemented his career in fine art painting and mural work.

Monumental Visions: The Muralist

Mora's artistic ambitions extended to the large scale of mural painting, a field experiencing a resurgence in the United States as part of the City Beautiful movement and a general interest in public art. His strong compositional skills and academic training made him well-suited for these demanding commissions. He created significant murals for various public and private buildings, integrating art with architecture.

One of his notable mural projects was for the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City, where he contributed historical panels. He also painted murals for the Lynn Public Library in Massachusetts and the Governor's Mansion in New Jersey. These large-scale works often depicted historical events, allegorical themes, or scenes representing local industry and culture, designed to educate and inspire the public.

His involvement extended to major expositions, including the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (1915) and potentially the St. Louis World's Fair earlier, although documentation for the latter is less clear regarding specific murals. He was also commissioned to create work for the Red Cross Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Mural painting allowed Mora to engage with grand themes and reach a broad audience, placing his work in the public sphere alongside contemporaries working on similar large-scale projects, such as the academic painter Kenyon Cox or the sculptor Daniel Chester French, famed for the Lincoln statue at the Lincoln Memorial.

The Portraitist

Portraiture was another important facet of Francis Luis Mora's diverse artistic output. His skill in capturing a likeness, combined with his ability to convey personality and status, made him a successful portrait painter. He received commissions from prominent individuals and institutions, including the most prestigious commission an American artist could receive: the White House.

Mora painted official portraits of President Warren G. Harding and President Woodrow Wilson, which hang in the White House collection. These works required not only technical skill but also the ability to project an image of dignity and leadership appropriate for the office. He reportedly also painted a portrait of the industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

His approach to portraiture combined the realism learned through his academic training with a painterly quality that kept the works from feeling stiff or photographic. He paid close attention to details of clothing and setting, which helped to establish the sitter's social context, but his primary focus remained the face and the suggestion of the individual's character. His portraits, like his other works, often show an awareness of historical precedents, particularly the grand manner of portraiture inherited from masters like Velázquez and Sargent, adapted to a modern American context.

Technical Versatility and Style

A hallmark of Francis Luis Mora's career was his exceptional technical versatility. He moved fluidly between different media, mastering oil painting, watercolor, tempera, charcoal drawing, and etching. Each medium allowed for different expressive possibilities, and Mora seemed equally comfortable with the rich textures of oil, the transparent luminosity of watercolor, and the linear precision of etching.

His style, while rooted in academic realism, was adaptable. In his Spanish scenes, one often finds dramatic lighting, strong contrasts, and vigorous brushwork, conveying energy and passion. His American genre scenes might employ a brighter palette and a more controlled, though still painterly, application of paint, emphasizing light and atmosphere in the tradition of his Boston School teachers. His illustrations required clear narrative composition and often detailed rendering, while his murals demanded bold design and legibility from a distance.

Throughout his diverse output, a consistent element is his strong draftsmanship. Whether in a quick charcoal sketch or a finished oil painting, the underlying structure and understanding of form are evident. He combined this technical facility with a romantic sensibility, particularly in his historical and Spanish subjects, but tempered it with keen observation when depicting contemporary life. This blend of traditional skill, romantic feeling, and modern subject matter defines his unique artistic signature. He skillfully navigated the space between academic tradition and the emerging currents of modern art, drawing from artists like Joaquín Sorolla, the contemporary Spanish painter whose sunny canvases were immensely popular in America, while retaining his own distinct voice.

A Respected Educator

Complementing his active career as a producing artist, Francis Luis Mora was also a dedicated and influential teacher. He shared his knowledge and experience with students at several prominent New York art schools. He taught at the Art Students League, where he himself had studied, connecting him to a lineage that included figures like Robert Henri and, later, students such as George Bellows and Edward Hopper (though they were contemporaries/near-contemporaries rather than direct students of Mora in most cases).

Mora also held teaching positions at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School, founded by William Merritt Chase) and the Grand Central School of Art. His reputation as a skilled artist across multiple disciplines made him a valuable instructor. He could offer practical guidance on painting techniques, composition, illustration, and likely etching as well. His background, bridging European traditions and American practices, would have provided students with a broad perspective.

Teaching provided Mora with another avenue to shape the art world and likely offered a source of steady income and intellectual engagement. His commitment to education underscores his position as a well-rounded figure within the New York art establishment of his time. Many successful artists of the period balanced their studio work with teaching, contributing to the training of the next generation.

Recognition and Legacy

During his lifetime, Francis Luis Mora achieved considerable recognition for his work. He received numerous awards, including the prestigious Carnegie Prize from the National Academy of Design, the Salmagundi Club's Shaw Purchase Prize, and the Rosenberg Purchase Prize from the San Francisco Art Association. His election as an Associate (ANA) in 1904 and a full Academician (NA) in 1906 to the National Academy of Design solidified his standing within the American art establishment. He was, notably, the first Hispanic artist to be elected to the Academy.

He was also a member of other important arts organizations, including the National Arts Club, the American Watercolor Society, the New York Water Color Club, the Salmagundi Club, and the Allied Artists of America. He was honored with membership in the Hispanic Society of America in 1914, recognizing his significant contributions to art related to Hispanic culture.

His works were acquired by major museums, ensuring their preservation and continued visibility. Today, paintings and works on paper by Francis Luis Mora can be found in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Academy of Design Museum, the Newark Museum, the Museum of the City of New York, the Georgia Museum of Art, and many others. Despite this recognition, his reputation perhaps faded somewhat in the later 20th century as artistic tastes shifted towards abstraction and more radical forms of modernism. However, recent scholarship and exhibitions, such as a significant retrospective at ACA Galleries in New York in 2016, have helped to re-evaluate his contributions and bring his diverse talents back into focus.

Personal Life and Character

Francis Luis Mora's personal life contained complexities that mirrored the richness of his artistic career. His marriage history was somewhat turbulent. He married Sophia ("Sonia") Brown Compton Young in 1900. She was also an artist. They later divorced. In 1932, he married May Safford, who had been his longtime housekeeper and model. This marriage also faced difficulties.

He had one daughter from his first marriage, Rosemary. Accounts suggest that his relationship with Rosemary was strained at times, and she was eventually sent to live with relatives in Spain. These personal challenges hint at a life lived with passion but also potential turmoil, aspects that may or may not be subtly reflected in the emotional tenor of his work.

Anecdotes suggest Mora was a man of considerable energy and engagement with the world. His contributions during World War I, creating posters and insignia, show a sense of civic duty. His active participation in numerous art clubs indicates a sociable nature and a commitment to the artistic community. His ability to sustain a career across painting, illustration, murals, and teaching points to a strong work ethic and remarkable adaptability.

Mora in the Tapestry of Art History

Francis Luis Mora occupies a unique position in American art history. As a Uruguayan-born artist of Spanish and French descent who became a prominent figure in the New York art world, he embodied a transatlantic cultural exchange. His work resists easy categorization. He was trained by American Impressionists (Benson, Tarbell) but drew heavily on Spanish Old Masters (Velázquez, Goya). He depicted contemporary American life with a sensitivity that aligns him broadly with realist trends (sharing subject interests with Ashcan artists like Henri and Sloan) but often with a more refined, less gritty approach.

His success as an illustrator places him within the Golden Age alongside Pyle and Wyeth, while his murals connect him to the tradition of public art championed by figures like Kenyon Cox. His portraiture stands comparison with contemporaries like Sargent in its technical skill and psychological insight. He maintained a commitment to representational art grounded in academic skill even as modernism was radically reshaping the artistic landscape through movements like Cubism and Fauvism, which were gaining attention during his mature career.

His legacy lies in this very diversity and his ability to synthesize disparate influences into a coherent, personal style. He demonstrated that traditional techniques could be applied to modern subjects and that an artist could successfully navigate the worlds of fine art, illustration, and public commissions. His Hispanic heritage provided a distinct cultural lens, enriching the predominantly Anglo-European narrative of American art at the time.

Conclusion

Francis Luis Mora was an artist of remarkable breadth and skill. From the sun-drenched landscapes and vibrant cultural scenes of Spain to the intimate interiors and public monuments of America, his work captured the spirit of his era with technical finesse and emotional depth. As a painter, illustrator, muralist, and teacher, he moved fluidly between different modes of artistic expression, achieving success and recognition in each. Rooted in the traditions of the Spanish masters yet fully engaged with the life of his adopted country, Mora created a body of work that bridges cultures and artistic disciplines. While perhaps overshadowed at times by more avant-garde movements, his art offers a rich and rewarding vision, reflecting a complex identity and a profound dedication to the craft of image-making in a rapidly changing world. His work remains a testament to the enduring power of representational art and the unique perspective he brought as an artist navigating between worlds.