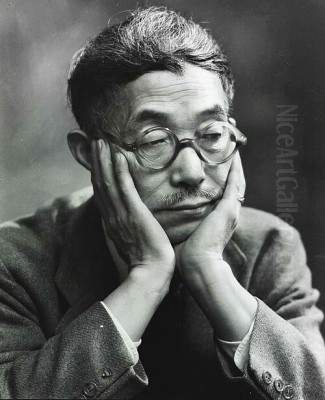

Yasuo Kuniyoshi stands as a pivotal, if sometimes tragically overlooked, figure in the landscape of 20th-century American art. Born in Japan and forging his career in the United States, Kuniyoshi's life and work are a testament to the complexities of cultural assimilation, the search for identity, and the enduring power of artistic expression in the face of adversity. His unique visual language, a sophisticated fusion of Eastern aesthetics and Western modernism, captivated audiences and critics alike, securing him a prominent place among his contemporaries. Yet, his journey was also marked by the profound challenges of being an immigrant, particularly during a period of intense geopolitical turmoil.

Early Life and a Fateful Journey West

Yasuo Kuniyoshi was born on September 1, 1889 (though some earlier sources incorrectly cited 1893), in Okayama, Japan. His early years in Japan provided a foundational, albeit perhaps subconscious, exposure to Japanese artistic traditions, which would later subtly permeate his mature work. Unlike many artists who show prodigious talent from a young age, Kuniyoshi's path to art was not immediate. His initial ambitions did not lie in painting; rather, like many young Japanese men of his era, he looked towards America as a land of opportunity.

In 1906, at the tender age of 17, Kuniyoshi embarked on a solo journey to the United States, initially landing in Seattle. His early experiences in America were characterized by the typical struggles of a new immigrant: language barriers, financial hardship, and a series of menial jobs to make ends meet. He soon moved to Los Angeles, where a chance encounter or perhaps a growing inclination led him to enroll in the Los Angeles School of Art and Design. It was here that the seeds of his artistic career were sown, and he began to formally engage with the principles of Western art.

New York: Forging an Artistic Identity

The lure of New York City, then solidifying its status as a burgeoning center for modern art, proved irresistible. Around 1910, Kuniyoshi relocated to New York, a move that would prove decisive for his artistic development. He immersed himself in the vibrant art scene, seeking out further instruction. He studied briefly at the National Academy of Design, but found its conservative approach stifling.

More significantly, Kuniyoshi enrolled at the independent Art Students League of New York, a crucible for many of America's most innovative artists. There, he studied under Kenneth Hayes Miller, a respected painter and influential teacher known for his emphasis on classical composition and Renaissance techniques, albeit applied to contemporary urban subjects. At the League, Kuniyoshi found himself among a dynamic group of peers who would also make their mark on American art, including Peggy Bacon, Alexander Brook (who would become a lifelong friend), Reginald Marsh, and Katherine Schmidt, who would later become his first wife.

Another crucial figure in Kuniyoshi's early New York years was Hamilton Easter Field, an artist, critic, publisher (of The Arts magazine), and patron. Field recognized Kuniyoshi's talent and provided him with crucial support, including studio space in Ogunquit, Maine, a popular summer art colony. Field's eclectic tastes and encouragement of modernism were undoubtedly influential. It was through Field's circle that Kuniyoshi also likely encountered the work of European modernists and American pioneers like Marsden Hartley and Walt Kuhn, the latter being a key organizer of the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show.

The Emergence of a Unique Style: The 1920s

The 1920s marked Kuniyoshi's true emergence as a distinctive voice in American art. His first solo exhibition was held at the Daniel Gallery in New York in 1922, a significant milestone. His work from this period is characterized by a captivating blend of naiveté and sophistication, drawing from diverse sources including American folk art, Japanese pictorial traditions, and the undercurrents of European modernism, particularly a subtle understanding of Post-Impressionism and a lyrical, almost dreamlike quality that some have linked to a nascent Surrealism.

His subjects were often whimsical and personal: cows (a recurring motif, perhaps symbolizing pastoral innocence or a gentle, earthy presence), fruits, plants, and pensive figures, often women or children. Works like Little Joe with Cow (c. 1923, sometimes titled Boy with Cow or Child with Cow) exemplify this early style, with its flattened perspective, slightly distorted figures, and a palette that, while often muted, possessed a rich, earthy depth. There's a sense of quiet poetry and an enigmatic narrative quality to these paintings.

Other notable works from this era include Village (1922), which showcases his ability to blend observed reality with a slightly fantastical, folk-art sensibility. His still lifes, such as Japanese Toy Tiger and Odd Objects (1932), though from slightly later, carry forward this interest in evocative arrangements that hint at personal symbolism and cultural memory. The "odd objects" often included items that spoke to both his Japanese heritage and his American experience.

During this decade, Kuniyoshi also traveled to Europe, spending time in Paris in 1925 and again in 1928. These trips exposed him directly to the work of European modern masters. He was particularly drawn to the work of artists like Jules Pascin, whose sensuous and melancholic depictions of women resonated with Kuniyoshi's own developing interest in the female figure. The influence of Pascin can be seen in the increasingly sophisticated and subtly eroticized nudes and female portraits Kuniyoshi began to produce. He also developed his skills in printmaking, particularly lithography, which became an important medium for him.

Maturity and Shifting Tones: The 1930s

As Kuniyoshi moved into the 1930s, his style continued to evolve. The earlier whimsy and folk-art inflections began to recede, replaced by a more somber, introspective, and technically refined approach. His palette often became darker, and his compositions more complex. Female figures remained a central preoccupation, but they were now imbued with a greater sense of psychological depth, often appearing melancholic, contemplative, or alluringly enigmatic.

Paintings like I'm Tired (1938) and Daily News (1935) showcase this shift. The women in these works are no longer the somewhat doll-like figures of his earlier period; they are more substantial, more worldly, and often tinged with a sense of weariness or introspection that perhaps reflected the anxieties of the Great Depression era. His still lifes also took on a more complex, almost brooding quality, with objects arranged in ways that suggested deeper, more unsettling meanings.

Throughout the 1930s, Kuniyoshi's reputation grew. He exhibited regularly and was included in important group shows. He also became an influential teacher, holding positions at the Art Students League (from 1933) and later at the New School for Social Research. He was respected by his peers, including artists like Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, and Georgia O'Keeffe, who were all part of the vibrant American modernist scene. He was also active in artists' organizations, advocating for the rights and welfare of fellow artists, a commitment that would continue throughout his life.

The War Years: An "Enemy Alien" Navigating Patriotism

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and America's subsequent entry into World War II, cast a dark shadow over Yasuo Kuniyoshi's life. Despite having lived in the United States for over three decades and being deeply integrated into the American art world, his Japanese birth rendered him an "enemy alien" in the eyes of the U.S. government. This status brought with it restrictions on his travel, confiscation of his camera and short-wave radio, and a profound sense of vulnerability and anguish.

Kuniyoshi, who considered himself a loyal American, was deeply distressed by Japanese militarism and the actions of his birth country. He sought to demonstrate his allegiance to the United States through his art. He was commissioned by the Office of War Information (OWI) to create propaganda posters aimed at demoralizing the Japanese enemy and bolstering American morale. These posters, often stark and graphic, depicted Japanese soldiers and leaders in a negative light, sometimes employing racial caricatures that were common in wartime propaganda. This work was undoubtedly a source of internal conflict for Kuniyoshi, a painful necessity in a time of crisis.

Beyond the OWI posters, his paintings from the war years reflect the turmoil and anxiety of the period. Works became darker, more symbolic, and filled with a sense of foreboding. One of his most powerful paintings from this era is Headless Horse Who Wants to Jump (1945) (sometimes translated as Headless Horse Who Wants to Leap). This disturbing image of a decapitated circus horse, still poised to perform, is a potent metaphor for the senseless destruction and disarray of war, and perhaps his own feeling of being psychically wounded or dismembered by his conflicted identity. The circus, once a site of fantasy and escape in his earlier work, now became a stage for tragedy and unease.

Other artists, like Ben Shahn and Philip Evergood, also engaged with social and political themes during this period, though Kuniyoshi's perspective was uniquely shaped by his personal predicament as a Japanese-American.

Post-War Recognition and Lingering Shadows

Despite the hardships of the war years, Kuniyoshi's stature in the American art world continued to grow. In 1948, he was honored with a major retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Remarkably, he was the first living artist to receive this honor, a testament to his significant contributions and the high regard in which he was held. This was a pinnacle of his career, affirming his place in the canon of American modernism.

His later works, from the late 1940s until his death, often carried a somber, almost funereal tone. The vibrant colors of his youth gave way to more muted, often monochromatic palettes, dominated by grays, blacks, and whites, with occasional flashes of unsettling color. His subjects remained familiar – women, still lifes, circus scenes – but they were imbued with a profound sense of melancholy and disillusionment. Works like Still Pond (1952) (also known as Quiet Pool) evoke a desolate, dreamlike atmosphere, where objects float in an ambiguous space, hinting at loss and the fragility of existence.

He continued to teach and was a leading figure in the art community. He was instrumental in the founding of Artists Equity Association in 1947, an organization dedicated to protecting artists' rights and promoting their economic welfare, and served as its first president. This demonstrated his deep commitment to his fellow artists and his belief in the importance of art in society. He was also selected to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1952, another significant international recognition.

However, the "enemy alien" designation and the inability to become a U.S. citizen (due to racially discriminatory immigration laws that were not fully reformed until after his death) remained a source of pain and frustration. This lingering sense of being an outsider, despite his achievements and deep connections to America, undoubtedly contributed to the melancholic strain in his later art.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns: A Deeper Look

Kuniyoshi's art is a rich tapestry woven from diverse threads. His early exposure to Japanese art, with its emphasis on flat planes, calligraphic line, and asymmetrical composition, provided a subtle underpinning to his work. This was overlaid with his embrace of American folk art's directness, unpretentious charm, and sometimes quirky perspectives.

From European modernism, he absorbed lessons in form and color. While never a strict adherent to any single modernist movement like Cubism or Fauvism, he selectively incorporated elements that suited his expressive needs. His figures often show a slight, elegant distortion reminiscent of Modigliani, and his compositions a sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships. The influence of Surrealism is also discernible, not in its overt dream-imagery, but in the enigmatic, often unsettling juxtapositions of objects and the psychological undercurrents that charge his scenes.

Key thematic concerns run through his oeuvre:

The Female Figure: Women are central to Kuniyoshi's art, evolving from innocent, doll-like figures to complex, psychologically nuanced individuals. They are often depicted in moments of introspection, boredom, or veiled sensuality.

Still Life: His still lifes are rarely mere arrangements of objects. They are carefully constructed tableaus, often imbued with personal symbolism and a sense of mystery. Objects from his Japanese heritage frequently appear alongside everyday American items, creating a dialogue between cultures.

Animals and Nature: Cows, horses, birds, and insects populate his canvases, often serving as symbolic counterparts to human figures or as elements in a dreamlike landscape.

The Circus: The circus motif, appearing throughout his career, transforms from a site of innocent wonder in his early work to a more ambiguous, even menacing, space in his later paintings, reflecting a loss of innocence and the anxieties of the modern world.

Identity and Displacement: Though not always overtly stated, the themes of identity, cultural hybridity, and a sense of displacement are palpable in his work, particularly in the later, more somber paintings.

Kuniyoshi and His Contemporaries

Kuniyoshi was an active participant in the New York art world. Beyond his early classmates at the Art Students League and mentors like Field, he interacted with a wide range of artists. He was part of a generation that included figures like Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, who were forging a distinctly American modernism. While their Precisionist style differed from Kuniyoshi's more lyrical approach, they shared a commitment to exploring contemporary American life through new artistic languages.

His engagement with social themes, particularly in his later work, connects him to the broader concerns of Social Realist painters like Raphael Soyer and Isaac Soyer, though Kuniyoshi's approach was always more personal and symbolic than overtly political. His teaching career brought him into contact with younger generations of artists, and his leadership in organizations like Artists Equity underscored his commitment to the artistic community. One can also consider his work in relation to other immigrant artists who enriched American culture, such as Arshile Gorky or, in sculpture, his fellow Japanese-American Isamu Noguchi, both of whom navigated complex identities in their adopted homeland.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Yasuo Kuniyoshi died on May 14, 1953, in New York City, at the age of 63. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to resonate for its artistic quality and its poignant exploration of human experience. His legacy is multifaceted:

A Master of Synthesis: He masterfully blended Eastern and Western artistic traditions, creating a style that was uniquely his own and contributed to the richness and diversity of American modernism.

An Artist of Emotional Depth: His work, particularly in his mature phase, is characterized by its psychological insight and emotional resonance, capturing a range of moods from whimsical fantasy to profound melancholy.

A Voice for the Displaced: His life and art give voice to the complexities of the immigrant experience, the challenges of cultural assimilation, and the search for identity in a world often marked by prejudice and conflict.

An Advocate for Artists: His role in founding and leading Artists Equity demonstrated his commitment to the welfare and professional standing of artists.

An Enduring Influence: His work is held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum (which organized a major retrospective in 2015, "The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi"), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. His art continues to be studied and admired for its technical skill, its aesthetic beauty, and its profound humanity.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his Abstract Expressionist successors like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning, who came to dominate the post-war American art scene, Yasuo Kuniyoshi's contributions are undeniable. He was a pioneer who navigated the treacherous waters of a bicultural identity, creating art that was both deeply personal and universally resonant. His journey, marked by both triumph and tribulation, serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of the human spirit and the vital role of art in bridging divides and illuminating the complexities of our shared world. His work remains a compelling chapter in the story of American art, deserving of continued attention and appreciation.