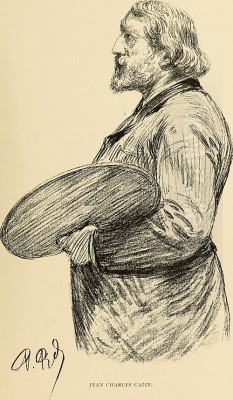

Jean-Charles Cazin stands as a significant yet often subtly categorized figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Active during a period of profound artistic transformation, Cazin navigated the currents of Realism, the burgeoning Impressionist movement, and lingering classical traditions, ultimately forging a unique and deeply personal style. Primarily celebrated for his evocative landscapes, particularly those capturing the nuanced light and atmosphere of his native Northern France, Cazin was also a accomplished painter of historical and religious subjects, a talented ceramicist, and an influential teacher. His work, characterized by its poetic sensitivity, harmonious palettes, and masterful rendering of light, secured him considerable acclaim during his lifetime and continues to resonate with viewers today. He remains a testament to an artist who drew from various influences but ultimately followed his own distinct vision, leaving behind a legacy of serene beauty and quiet emotional depth.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Jean-Charles Cazin was born on May 25, 1841, in Samer, a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department of Northern France. His father was a respected physician, and the initial expectation was that Jean-Charles would follow him into the medical profession. However, the young Cazin displayed an undeniable artistic inclination from a very early age. Reports suggest that by the age of five, he was already deeply fascinated by the natural world, spending hours observing its details and attempting to capture them. This innate sensitivity to his surroundings and a burgeoning desire to translate them into visual form proved stronger than familial expectations.

Recognizing his son's passion and talent, Cazin's father eventually relented, allowing him to pursue an artistic education. This decision set Cazin on a path that would lead him away from medicine and towards the ateliers and salons of the French art world. His early immersion in the landscapes of Pas-de-Calais would profoundly shape his artistic sensibilities, instilling in him a lifelong attachment to the specific light, terrain, and atmosphere of the region, which would become the hallmark of his most celebrated works.

Formative Years and Influences

Cazin's formal art education took place primarily in Paris. He enrolled at the École Gratuite de Dessin (Free School of Drawing), a well-regarded institution known for its practical approach. Crucially, he studied under Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, a highly influential teacher whose pedagogical methods were somewhat unconventional for the time. Lecoq de Boisbaudran emphasized drawing from memory, training his students to observe intensely and then recreate subjects without the model present. This rigorous training honed Cazin's visual recall and likely contributed to the evocative, rather than strictly literal, quality of his later landscapes.

During his studies, Cazin also received instruction from Antoine Barye, the renowned sculptor celebrated for his dynamic animal figures. While Cazin primarily focused on painting, exposure to Barye's emphasis on form and structure may have subtly informed his compositional sense. Furthermore, Cazin, like many artists of his generation, felt the influence of the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, known for their detailed rendering, vibrant color, and often literary or historical subject matter. This influence might be discerned in the clarity and narrative elements present in some of his earlier works.

His artistic development was also shaped by personal connections. He married Marie Guillet, who became Marie Cazin, herself a talented painter and sculptor. Marie had studied with the famous animal painter Rosa Bonheur, bringing another strand of artistic influence into their shared life and potentially reinforcing Jean-Charles's connection to traditions of careful observation and skilled representation, even as he developed his own unique approach.

Early Career: Teaching, London, and Ceramics

Before fully establishing himself as an independent artist, Cazin engaged in teaching. From 1863 to 1865, recommended by his former teacher Lecoq de Boisbaudran, he served as a drawing instructor at the École Spéciale d'Architecture in Paris. This position indicates his early competence and the respect he commanded within educational circles. In 1868, his career took another significant step when he was appointed director of the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) and curator of the museum in Tours. This dual role provided him with administrative and curatorial experience, broadening his engagement with the art world beyond personal creation.

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 prompted a move. Sources suggest disagreements with museum officials, possibly exacerbated by the wartime atmosphere, led Cazin and his family to relocate to England. This period in London proved artistically fruitful in unexpected ways. He connected with fellow artists, including the French expatriate Alphonse Legros, a painter and etcher known for his sober realism, and likely encountered figures associated with the London art scene, potentially including James McNeill Whistler, whose tonal harmonies might have resonated with Cazin's own developing sensibility.

During his time in England, Cazin developed a keen interest in ceramics. He began working with the Fulham Pottery, designing and decorating stoneware. This venture into applied arts showcased his versatility and his interest in craftsmanship. The ceramics he produced, often featuring decorative motifs and demonstrating a refined aesthetic sense, represent an important, though less frequently discussed, facet of his artistic output. This period abroad broadened his horizons and introduced him to different artistic currents and possibilities.

Return to France and Mature Style

Upon returning to France after the war, Cazin chose not to return to Paris immediately but settled near Boulogne-sur-Mer, close to his native region of Pas-de-Calais. This return marked a significant phase in his artistic development, where his focus increasingly shifted towards landscape painting, drawing inspiration from the familiar dunes, marshes, villages, and coastlines of Northern France. While he continued to paint historical and religious subjects, these were often integrated into contemporary landscape settings, lending them a unique blend of timeless narrative and specific, observed reality.

His earlier works, such as The Flight into Egypt (1877) and Hagar and Ishmael (1880), gained him recognition at the Paris Salon. These paintings demonstrated his ability to handle complex compositions and imbue traditional themes with a palpable sense of atmosphere and human emotion, rendered with a clarity influenced by his Realist training but softened by a growing sensitivity to light. Hagar and Ishmael, in particular, was widely praised and helped establish his reputation.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Cazin solidified his position as a leading landscape painter. He exhibited regularly at the Salon, gaining critical acclaim and attracting patrons. His distinctive approach, which captured the subtle poetry of everyday scenes and the transient effects of light, distinguished him from both the academic painters and the more radical Impressionists. He received official recognition, being made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1882 and promoted to Officer in 1889, confirming his status within the French art establishment.

The Cazin Style: Light, Atmosphere, and Subject Matter

Jean-Charles Cazin's artistic style is often described as occupying a unique space between Realism and Impressionism, yet it defies easy categorization. He shared the Realists' commitment to observation and depicting the tangible world, but imbued his scenes with a subjective, poetic quality more aligned with later movements. Unlike the core Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Cazin rarely employed broken brushwork or the high-keyed palette associated with capturing fleeting moments of intense sunlight. Instead, he excelled at rendering the softer, more diffused light of dawn, twilight, or moonlit nights.

His mastery of light is perhaps his most defining characteristic. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture crepuscular effects – the subtle gradations of color and tone as day transitions into night. His moonlit scenes, like the aptly titled Moonrise, are renowned for their tranquility and evocative power. He achieved these effects through carefully modulated tones and harmonious color palettes, often favoring muted greens, ochres, grays, and blues, which perfectly conveyed the gentle melancholy or serene stillness of his chosen moments.

Atmosphere was paramount in Cazin's work. He sought to capture not just the visual appearance of a landscape but its emotional resonance. His paintings often evoke feelings of peace, solitude, or quiet contemplation. Whether depicting a simple cluster of cottages under a vast sky, a lonely road winding through dunes, or a biblical scene unfolding in a recognizable French landscape, a consistent mood of gentle introspection prevails. This focus on mood links him to the Barbizon School painters like Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot, who also sought the poetic essence of rural life and landscape, though Cazin's technique and light effects were distinctly his own.

His subject matter ranged from pure landscapes, often featuring the humble architecture and terrain of Pas-de-Calais, to historical and biblical narratives. Works like Tobias and the Angel or Judith demonstrate his ability to handle traditional themes, but he often placed these figures within naturalistic landscape settings, grounding the epic or sacred in the familiar. This integration of figure and landscape is seamless, with the environment playing a crucial role in setting the emotional tone of the narrative. He also explored decorative painting, sometimes compared in spirit to the large-scale, idealized works of Puvis de Chavannes, though Cazin's approach remained more intimate and grounded in observed reality.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Jean-Charles Cazin's artistic achievements. His early Salon success, Hagar and Ishmael (1880), depicts the biblical figures abandoned in the wilderness. Cazin sets the scene not in an imagined desert but in a landscape strongly reminiscent of the sandy dunes near his home, rendering their plight with poignant realism and atmospheric depth. The subdued light and vast, indifferent landscape underscore the figures' vulnerability.

The Flight into Egypt (1877) similarly integrates a sacred narrative into a familiar setting, showcasing his ability to blend history painting with landscape. His treatment of light, likely depicting dusk or dawn, adds to the quiet drama and intimacy of the scene. Later religious works like Tobias and the Angel and Judith continued this approach, praised for their harmonious color and sensitive portrayal of mood through landscape.

Among his pure landscapes, Moonrise is iconic, capturing the silvery light and profound stillness of a lunar landscape with exceptional skill. The Great Windmill and the Rainbow combines elements of rural architecture with a transient natural phenomenon, demonstrating his eye for capturing specific moments within the landscape while maintaining an overall sense of timelessness. The Quarry of Monsieur Pascal near Nanterre shows his ability to find beauty and compositional interest in more industrial or worked landscapes, rendered with his characteristic attention to light and detail.

Works like Returning Home or Village by the Seine (1890) exemplify his talent for depicting the quiet charm of rural life, focusing on the interplay of light on simple structures and the surrounding environment. Landscape (1893) is a broader title likely encompassing many works that showcase his mature style – serene, subtly lit scenes rendered with a smooth finish and deep feeling for place. His Souvenir de Fête, painted from memory, highlights the effectiveness of his Lecoq de Boisbaudran training. These paintings, whether grand narratives or simple landscapes, are united by Cazin's distinctive vision and technical mastery.

Connections and Contemporaries

Jean-Charles Cazin's career unfolded amidst a vibrant and evolving Parisian art world, and he maintained connections with numerous prominent artists. His teacher, Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, was a pivotal figure in his formation. His friendship and collaboration with Alphonse Legros, particularly during his time in London, were significant. He was also friends with Henri Fantin-Latour, known for his group portraits of artists and writers as well as his exquisite still lifes, and Théodule Ribot, a painter associated with Realism, known for his dramatic use of chiaroscuro.

Cazin's relationship with Auguste Rodin provides a fascinating anecdote. Rodin, the preeminent sculptor of the era, asked Cazin to model for the figure of Saint Peter in his monumental bronze group, The Burghers of Calais. Although Cazin was not elderly at the time, Rodin reportedly aged his features in the final sculpture to better fit the character, showcasing the artistic license taken even when working with a fellow artist as a model. This connection underscores Cazin's standing within the artistic community.

While not an Impressionist himself, Cazin worked concurrently with the movement's key figures like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas. His work offers a contrast to theirs – where they often pursued fleeting effects with broken color and visible brushwork, Cazin sought a more finished, tonal, and atmospheric rendering of light. Comparisons are sometimes drawn between Cazin's idealized landscapes and decorative works and those of Puvis de Chavannes, a major figure in Symbolist and mural painting.

His work also shows affinities with the earlier Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot, who elevated landscape and peasant life as worthy subjects, often imbuing them with poetic or spiritual significance. Cazin built upon this legacy, adapting it to his own time and place. He likely knew or was aware of the work of Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of Realism, though Cazin's temperament led him to a gentler, less confrontational form of realism. His interactions extended later in his life, influencing younger artists like the Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck. His wife, Marie Cazin, was also a respected artist, creating a partnership deeply embedded in the art world, connected through her teacher Rosa Bonheur to another lineage of French painting.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Legacy

Jean-Charles Cazin achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His regular participation in the Paris Salon brought his work to public and critical attention. The awards bestowed upon him, including the Legion of Honour (Chevalier in 1882, Officer in 1889) and Grand Prizes at the prestigious Exposition Universelle in Paris in both 1889 and 1900, solidified his reputation as a major figure in contemporary French art.

A pivotal moment for his international reputation occurred in 1893 when he traveled to the United States. An extensive exhibition of nearly 180 of his works was held at the galleries of the American Art Association in New York. This show, comprising pieces from his personal collection as well as works already owned by American collectors, was a resounding success. It generated significant enthusiasm for his art in America, leading to numerous acquisitions by private collectors and museums, and firmly establishing his name across the Atlantic.

Consequently, Cazin's paintings entered major public collections both in France and internationally. Today, his works can be found in prominent institutions such as the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art (inheriting works from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), the Corcoran Gallery of Art collection, and the Frick Art & Historical Center in Pittsburgh, among many others.

His legacy lies in his unique contribution to landscape painting. He demonstrated that a profound connection to a specific region, combined with a masterful control of light and atmosphere, could produce works of enduring poetic beauty. He offered an alternative path during a time dominated by Impressionism, proving that subtlety, harmony, and a finished surface could be just as modern and expressive. He influenced subsequent landscape painters who valued mood and atmosphere over purely optical effects, and his work continues to be admired for its technical skill and quiet emotional depth.

Personal Life and Character

Jean-Charles Cazin's personal life appears to have been relatively stable, centered around his family and his art. His marriage to Marie Cazin (née Guillet) was a partnership of two accomplished artists. Marie was a recognized painter and sculptor in her own right, exhibiting alongside her husband and pursuing her own successful career. They often worked in proximity, and their shared artistic life undoubtedly provided mutual support and stimulus. They had a son, Jean-Michel Cazin, who also became an artist, continuing the family's creative legacy.

Anecdotal accounts suggest a certain duality in Cazin's personality. Outwardly, he could appear reserved, serious, even somewhat austere, leading some contemporaries to misinterpret him as detached or overly intellectual. However, those who knew him better perceived a deep wellspring of emotion and sensitivity beneath the surface. This inner emotional life found its outlet in the poetic and often melancholic beauty of his paintings. His art reveals a profound empathy for nature and a capacity for capturing subtle moods that belies any superficial impression of coolness.

His dedication to art extended to education, though not without challenges. His tenures as a teacher and director in Paris and Tours demonstrate a commitment to fostering artistic talent. He reportedly attempted, along with his friend Alphonse Legros, to establish a new kind of art school, though this ambitious project ultimately did not come to fruition. This suggests an innovative spirit and perhaps a desire to reform art education according to his own principles, likely rooted in the memory-training methods of Lecoq de Boisbaudran combined with a deep respect for craftsmanship.

Cazin passed away on March 17, 1901, at the age of 59, in Le Lavandou, Var, on the Mediterranean coast, though he remained most closely associated with the landscapes of the North. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its distinctive qualities.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Jean-Charles Cazin occupies a unique and respected place in the history of 19th-century French art. He was an artist who absorbed the lessons of Realism, acknowledged the innovations of Impressionism, and yet charted his own course. His profound connection to the landscapes of Northern France, combined with an exceptional sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere, resulted in works of enduring poetic power. Whether depicting the quiet dignity of rural life, the transient beauty of a sunset, the ethereal glow of moonlight, or embedding timeless narratives within familiar settings, Cazin's paintings resonate with a quiet emotional depth and technical mastery.

His versatility as a painter, ceramicist, and educator speaks to a broad artistic engagement. While perhaps less revolutionary than some of his contemporaries, Cazin's dedication to his singular vision, his harmonious compositions, and his unparalleled ability to capture the soul of a landscape secured him lasting recognition. His art offers a contemplative counterpoint to the dynamism of his era, inviting viewers into a world of serene beauty, subtle emotion, and the enduring magic of light. Jean-Charles Cazin remains a master whose works continue to reward close looking and quiet reflection.