Frank Duveneck stands as a pivotal figure in American art history, renowned not only for his powerful realist paintings and etchings but also for his profound impact as an influential art educator. Born in the American Midwest to German immigrant parents, Duveneck bridged the artistic worlds of Europe and the United States, bringing a vigorous, painterly style learned in Munich back to his homeland. His career spanned a dynamic period of artistic change, and his work, along with that of his students, played a significant role in moving American art beyond its established traditions towards a more modern sensibility. As a painter, etcher, and teacher, Duveneck left an indelible mark, celebrated for his technical virtuosity, his insightful portrayals of human character, and his mentorship of a generation of artists.

Early Life and Formative Training

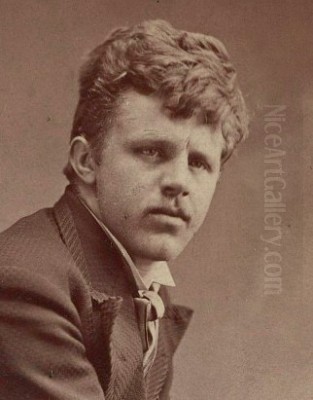

Frank Duveneck was born Frank Decker on October 9, 1848, in Covington, Kentucky, a city situated just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. His parents, Bernard Decker and Katherine Siemers Decker, were immigrants from Westphalia, Germany. Tragedy struck early when his father died during a cholera epidemic in 1849. His mother later married Joseph Duveneck, a proprietor of a beer garden, and young Frank subsequently adopted his stepfather's surname. This German-American heritage and upbringing in a community with strong ties to German culture would significantly shape his early experiences and artistic inclinations.

Duveneck's artistic talents emerged at a young age. He began his artistic journey locally, receiving initial instruction from a church painter named Johann Schmitt. Demonstrating considerable aptitude, he became an apprentice at the Cincinnati firm of Lamprecht & Tieman, which specialized in decorating Catholic churches in the Midwest with murals and other embellishments. This early work provided him with practical experience in handling paint on a large scale and likely instilled a discipline and familiarity with traditional religious iconography, though his later easel painting would diverge significantly in style and subject matter.

Recognizing the need for more formal and advanced training to develop his burgeoning talent, Duveneck, encouraged by his mentors and likely supported by his family and community, made the pivotal decision to travel to Germany. In 1869, at the age of 21, he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. This move placed him at the heart of one of Europe's most vibrant and progressive art centers, setting the stage for a dramatic transformation in his artistic development.

The Munich Years and the Development of a Style

Munich in the 1870s was a crucible of artistic innovation, challenging the polished academicism favored in Paris. The Munich School emphasized realism, painterly bravura, and the study of Old Masters, particularly those of the Dutch and Spanish Golden Ages. Duveneck thrived in this environment. He studied primarily under Wilhelm von Diez, a prominent figure at the Academy known for his historical genre scenes and emphasis on direct observation and vigorous technique. Alexander Strauber was another of his instructors mentioned in some accounts.

Beyond his formal teachers, Duveneck was profoundly influenced by the leading figures of Munich realism, especially Wilhelm Leibl. Leibl and his circle championed a style characterized by direct painting (alla prima), often using dark, rich palettes, dramatic chiaroscuro, and unidealized depictions of everyday people. Duveneck quickly absorbed these principles, developing a distinctive style marked by bold, fluid brushwork, a somber but resonant color palette, and a remarkable ability to capture the psychological presence of his subjects.

His technical skill was extraordinary, drawing comparisons to masters like Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez for the sheer energy and confidence of his paint application. He often worked directly on the canvas without preliminary drawings, building form and capturing likeness with swift, decisive strokes. This approach lent his portraits an immediacy and vitality that astonished viewers accustomed to more tightly rendered academic work. His talent was quickly recognized at the Academy, where he won prizes and earned the respect of his peers and instructors.

Early Recognition and Return to America

Duveneck's Munich paintings, particularly his portraits and character studies, began to attract significant attention. Works like the iconic The Whistling Boy (1872), depicting a street urchin with striking realism and bravura brushwork, showcased his mastery of the Munich style. This painting, along with others featuring working-class or peasant figures rendered with dignity and psychological depth, established his reputation.

He returned to Cincinnati in 1873, bringing with him the techniques and artistic philosophy he had absorbed in Munich. He began teaching at the Ohio Mechanics Institute, sharing his European training with local students. His work caused a sensation when exhibited in Boston in 1875. Critics and fellow artists were struck by the power and modernity of his style, which stood in stark contrast to the prevailing tastes shaped by the Hudson River School's landscape tradition and the more polished styles favored by East Coast academic painters.

The writer Henry James, a keen observer of the art world, was among those who recognized Duveneck's talent, praising his "unerring hand" and the "unmistakable stamp of life" in his portraits. John Singer Sargent, another American expatriate artist who achieved international fame, later famously declared Duveneck "the greatest talent of the brush of this generation." This early acclaim cemented Duveneck's position as a significant new force in American art, even though his style remained somewhat outside the mainstream.

The "Duveneck Boys"

Duveneck's charisma and artistic prowess naturally attracted a following of younger American artists who were eager to learn from him and experience the Munich style firsthand. When Duveneck returned to Munich in 1875, and later traveled to Italy, a group of devoted students accompanied him, becoming known collectively as the "Duveneck Boys." This informal group included artists who would go on to have significant careers in their own right.

Prominent among the "Duveneck Boys" were John Henry Twachtman, known for his later development into a leading American Impressionist; John White Alexander, who became a celebrated portraitist and muralist; Joseph DeCamp, a key figure in the Boston School of painting; Kenyon Cox, an influential academic painter, muralist, and writer; Otto Bacher, who became known for his etchings and paintings; Theodore Wendel, who also embraced Impressionism; and Julius Rolshoven, among others.

These students were drawn to Duveneck's direct painting methods, his emphasis on capturing character, and his rejection of fussy academic finish. They worked closely with their mentor, often sharing studios and traveling together, particularly during their time in Munich, Florence, and Venice. Their early work often strongly reflected Duveneck's influence, featuring similar dark palettes, vigorous brushwork, and realist subjects. While many, like Twachtman and Wendel, later evolved towards Impressionism, their foundational training with Duveneck remained a crucial part of their artistic development.

Italian Sojourns and Artistic Evolution

From the late 1870s through much of the 1880s, Duveneck spent considerable time in Italy, primarily in Florence and Venice, often accompanied by his "Boys." This period marked a noticeable evolution in his art. While maintaining his characteristic bold brushwork, his palette began to lighten under the influence of the Italian sun and the art of Venice. The somber tones of Munich gradually gave way to brighter colors and a greater interest in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere.

In Venice, he shared a studio for a time with William Merritt Chase, another prominent American artist who had also studied in Munich but developed a lighter, more cosmopolitan style. He also interacted with James McNeill Whistler, whose aestheticism and experiments with tonal harmony offered a different artistic path. Duveneck's Venetian scenes, both paintings and etchings, often depict the city's canals, architecture, and daily life with a newfound atmospheric sensitivity, though still retaining a robust sense of form.

Works from this period, such as Water Carriers, Venice (c. 1884) and various views of the Venetian lagoon (e.g., Shipping on the Venetian Lagoon at Night, 1884) or Florentine subjects like Florentine Flower Girl (1880), demonstrate this shift. While not fully embracing Impressionism's broken color techniques, Duveneck incorporated a looser handling and a more vibrant palette, reflecting the influence of his surroundings and possibly the evolving tastes of the era. His focus remained largely on figurative work, but landscape and cityscape elements became more prominent.

Mastery in Etching

Alongside his painting, Duveneck developed considerable skill as an etcher, particularly during his time in Venice between 1880 and 1885. Encouraged perhaps by the example of Whistler, who was also creating celebrated Venetian etchings during this period, Duveneck produced a significant body of work in the medium. He created approximately 37 etchings, mostly focusing on Venetian scenes – canals, bridges, doorways, and lagoon views.

His etchings are characterized by a vigorous and expressive line, rich tonal effects achieved through intricate hatching and selective wiping of the ink (plate tone), and a strong sense of composition. Works like The Riva degli Schiavoni, No. 1 and San Pietro in Castello are considered masterpieces of the medium, capturing the unique atmosphere and picturesque decay of Venice with remarkable directness and technical skill. Otto Bacher, one of the "Duveneck Boys," was also deeply involved in etching at this time and later wrote about their experiences.

Duveneck's etchings were exhibited and well-received, further enhancing his reputation. They stand alongside Whistler's as some of the most important contributions to the Etching Revival movement by American artists working in Venice during the late 19th century. They demonstrate his versatility and his ability to translate the energy of his brushwork into the linear medium of printmaking.

Marriage, Tragedy, and Return

In Florence, Duveneck taught painting to a number of students, including the talented and accomplished Elizabeth Boott. Born in Boston to a wealthy and cultured expatriate family, Elizabeth (known as "Lizzie") was a friend of the novelist Henry James and moved in sophisticated social circles. Despite the significant differences in their backgrounds – Duveneck being the son of working-class immigrants and Boott coming from Brahmin privilege – they fell in love.

Frank Duveneck and Elizabeth Boott married in Paris on March 25, 1886. They settled in the Villa Castellani outside Florence (a property owned by her family), and their son, Frank Boott Duveneck, was born the following year. Their marriage, however, was tragically short-lived. Elizabeth contracted pneumonia and died suddenly in Paris on March 22, 1888, less than two years after their wedding.

Her death was a devastating blow to Duveneck. He largely abandoned painting for a period and turned his attention to sculpture, creating a poignant, recumbent memorial effigy for her grave in the Allori Cemetery in Florence. The sculpture, a sensitive portrayal in bronze inlaid with gold, is considered one of his most moving works and earned accolades when a version was exhibited. The loss profoundly affected him, and while he eventually resumed painting and teaching, the exuberant productivity of his earlier years seemed somewhat diminished.

Later Career: The Sage of Cincinnati

Following his wife's death, Duveneck spent time traveling between Italy and the United States. He eventually settled permanently back in the Cincinnati area around 1889-1890. He became increasingly involved with the Art Academy of Cincinnati, where many of his former "Boys" were now teaching or influential figures. He joined the faculty formally around 1900 (some sources say 1908) and served as its chairman after 1904, becoming a revered figure in the city's art community.

He dedicated much of his later life to teaching, mentoring generations of Cincinnati artists. His teaching emphasized solid draftsmanship, direct painting techniques, and understanding of form, carrying forward the principles he had learned in Munich but adapted through his own experiences. While he continued to paint, producing portraits, landscapes, and occasional other subjects, his output was less prolific than in his youth. His later style often retained the solidity of his Munich training but sometimes showed the lighter palette adopted in Italy.

Duveneck became an elder statesman of American art, particularly in the Midwest. He received numerous honors, including invitations to serve on international art juries and an honorary doctorate. He remained connected to the national art scene, exhibiting occasionally, but his primary focus was on his teaching and the development of the Art Academy of Cincinnati. He died in Cincinnati on January 3, 1919, at the age of 70, leaving behind a rich legacy as both creator and educator.

Artistic Style Revisited: Realism and Virtuosity

Frank Duveneck's artistic style is primarily defined by its roots in Munich Realism. Key characteristics include:

Direct Painting (Alla Prima): Applying paint directly to the canvas, often wet-into-wet, without extensive underpainting or glazing, aiming for immediate effect.

Bold Brushwork: Using visible, energetic, and often broad brushstrokes to define form and texture, conveying a sense of spontaneity and technical confidence.

Chiaroscuro: Employing strong contrasts between light and shadow to model form and create dramatic impact, particularly evident in his early portraits.

Dark Palette (Early Work): Utilizing rich, deep earth tones, blacks, and grays, reminiscent of Old Masters like Rembrandt and Hals, to create a somber yet powerful mood.

Psychological Realism: Focusing on capturing the character and inner life of his subjects, especially in portraits, often depicting ordinary people with dignity and intensity.

Evolution Towards Light (Later Work): Incorporating a brighter palette and greater attention to atmospheric light effects, particularly after his time in Italy, showing a subtle absorption of Impressionist sensibilities without fully adopting the style.

His work consistently demonstrates a mastery of paint handling and a deep understanding of human anatomy and character. While influenced by European trends, his art retained a distinctly American vigor and directness.

Critical Reception and Historical Significance

During his lifetime, Frank Duveneck experienced periods of significant acclaim, particularly in the 1870s and early 1880s when his Munich-style work burst onto the American scene. He was hailed by progressive critics and artists like Henry James and John Singer Sargent. However, his style was also sometimes criticized for its perceived "foreignness" or darkness, especially as Impressionism gained favor in America. His subject matter, often focusing on working-class individuals or peasant types, could also be seen as challenging the more genteel tastes prevalent in Gilded Age America.

After his wife's death and his return to Cincinnati, his national profile somewhat diminished, although he remained highly respected as a teacher. For a period in the mid-20th century, his reputation was somewhat eclipsed by the rise of modernism and later abstract movements. However, subsequent reassessments have firmly re-established his importance.

Today, Duveneck is recognized as a major figure in American Realism, a crucial link between European artistic developments and the American art scene. He is lauded for his technical brilliance, the psychological depth of his portraiture, and his significant contribution to American printmaking. Perhaps most importantly, his legacy as an educator is undeniable. Through his direct teaching and the subsequent careers of the "Duveneck Boys" and later students at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, his influence extended far beyond his own canvases, helping to shape the course of American art at the turn of the 20th century. His work is held in major museum collections across the United States, ensuring his enduring presence in the narrative of American art history.