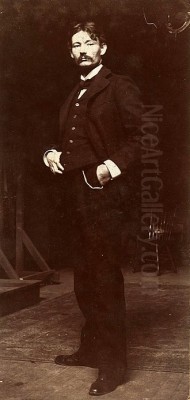

Introduction: A Pivotal Figure

Robert Henri stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of American art. Active during a transformative period spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Henri was not only a gifted painter but also a charismatic and revolutionary teacher. He played a crucial role in steering American art away from the conservative constraints of academic tradition and towards a more vital, modern realism rooted in the direct observation of contemporary life. As the central figure of the Ashcan School and the organizer of the landmark exhibition of "The Eight," Henri championed artistic independence and encouraged a generation of artists to find beauty and significance in the everyday realities of urban America. His legacy endures through his powerful paintings and his widely read book, The Art Spirit.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Robert Henri was born Robert Henry Cozad on June 24, 1865, in Cincinnati, Ohio. His early life was marked by upheaval. His father, John Jackson Cozad, was a professional gambler and land developer who founded the town of Cozaddale, Ohio, and later Cozad, Nebraska. A violent dispute in Nebraska involving his father and a rancher named Alfred Pearson led to Pearson's death. To escape the ensuing scandal and potential legal repercussions, the family fled east, eventually settling in Atlantic City, New Jersey. During this time, the family adopted new identities; Robert began using the name Robert Earl Henri (pronounced Hen-rye), a fiction he maintained for the rest of his life, concealing his past.

This dramatic background perhaps contributed to Henri's later empathy for outsiders and his focus on individual character. His formal art education began in 1886 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. PAFA was then a significant center for realist painting, largely due to the lingering influence of Thomas Eakins, although Eakins himself had been forced to resign shortly before Henri arrived. Henri studied primarily under Thomas Anshutz, Eakins's protégé, who continued the tradition of rigorous anatomical study and direct observation. He also studied with James B. Kelly. At PAFA, Henri began to form connections with other young artists who would later become his close associates.

Parisian Studies and European Influences

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Henri traveled to Paris in 1888, the epicenter of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a popular alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts, studying under the academic painters William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. While respecting the technical skills taught, Henri found the rigid academic approach stifling. He was more drawn to the spirit of Impressionism and the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements, although he never fully adopted their styles. He spent time sketching and painting independently, particularly enjoying landscapes in Brittany and Barbizon.

During his time in Europe, which included several trips between 1888 and 1900, Henri absorbed a wide range of influences. He admired the realism and psychological depth of Édouard Manet, the atmospheric effects of James McNeill Whistler, and the bravura brushwork and profound humanism of Old Masters like Diego Velázquez, Frans Hals, and Rembrandt. These artists, known for their direct painting techniques and ability to capture the essence of their subjects with economy and vitality, profoundly shaped Henri's developing aesthetic. He learned to appreciate the expressive potential of paint itself and the importance of capturing a subject's inner life, not just their external appearance. He briefly gained admission to the École des Beaux-Arts but found independent study and museum visits more valuable.

Return to Philadelphia and the Seeds of Rebellion

Henri returned to Philadelphia in 1891 and soon began teaching at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. It was here that his exceptional talent as an educator first blossomed. He gathered around him a group of talented young newspaper illustrators who were eager to pursue painting. This group included William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan. They met frequently in Henri's studio (No. 806 Walnut Street) to discuss art and life, sketch, and critique each other's work. Henri encouraged them to abandon the idealized subjects favored by the academies and instead draw inspiration from their immediate urban surroundings, using their skills honed as illustrators to capture the raw energy of the city.

These gatherings, often informal and lively, laid the groundwork for what would later become the Ashcan School. Henri urged his followers to paint quickly, capturing fleeting moments and conveying the immediacy of experience. He stressed the importance of personal vision and emotional honesty over polished technique for its own sake. This Philadelphia circle represented a nascent rebellion against the genteel tradition that dominated American art at the time, setting the stage for a more robust and distinctly American form of realism. Henri's charisma and passionate advocacy for a vital, contemporary art made him the natural leader of this emerging movement.

The Ashcan School: Painting Urban Reality

In 1900, Henri moved to New York City, which was rapidly becoming the nation's cultural and artistic hub. Many of his Philadelphia associates, including Sloan, Glackens, and Luks, soon followed. New York, with its teeming immigrant populations, bustling streets, towering skyscrapers, and stark social contrasts, provided fertile ground for the type of art Henri championed. He continued to teach, first at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School, where he replaced William Merritt Chase) and later establishing his own Henri School of Art. His studio and classes became magnets for young artists seeking an alternative to the conservative National Academy of Design.

The term "Ashcan School" was actually coined derisively by a critic years later, but it aptly captured the group's focus on the grittier, unglamorous aspects of city life – back alleys, tenements, saloons, boxing matches, crowded markets, and working-class people. Henri and his followers, including later students like George Bellows, depicted the urban landscape with an unflinching honesty and a deep sense of humanism. They sought the "ash cans" and "snow heaps" of the city, finding beauty and significance where traditional art saw only ugliness or subjects unworthy of depiction. Their work was characterized by dark palettes, vigorous brushwork, and a sense of capturing a specific moment in time. Henri himself excelled at portraits and urban scenes, imbuing his subjects with dignity and vitality.

The Eight and the Challenge to the Establishment

Henri's dissatisfaction with the art establishment, particularly the conservative jury system of the National Academy of Design (NAD), reached a boiling point in 1907. When paintings by Henri and his circle were rejected or poorly hung at the NAD's annual exhibition, he decided to organize an independent show. He gathered a group of eight artists: himself, his four core Philadelphia associates (Sloan, Glackens, Luks, Shinn), and three other artists working in different, though still relatively modern, styles – Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast. Davies, Prendergast, and Lawson worked in more lyrical, Post-Impressionist, or Symbolist modes, making "The Eight" a stylistically diverse group united primarily by their opposition to the NAD's exclusivity.

Their landmark exhibition opened at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City in February 1908. It was a succès de scandale, attracting large crowds and generating significant press coverage, both positive and negative. Critics were divided; some praised the vitality and American character of the work, while others condemned its perceived crudeness and focus on "vulgar" subjects. The exhibition was significant not just for the art it displayed but for its assertion of artistic independence. It demonstrated that artists could successfully organize and exhibit outside the established academic system, paving the way for future independent shows, including the pivotal Armory Show of 1913 (in which Henri also participated, helping to organize the American section). "The Eight" as a formal group only exhibited together once, but their defiant gesture marked a turning point in American art history, signaling the rise of modernism.

Henri the Educator: Shaping a Generation

Beyond his own painting and his role in organizing artists, Henri's most profound and lasting impact may have been as a teacher. He taught at various institutions, including the New York School of Art, the Art Students League of New York (where he was a highly popular instructor for many years), and his own short-lived Henri School of Art. He possessed a rare ability to inspire students, encouraging them to find their own voices and connect their art deeply to their own experiences and personalities. He famously told his students, "Art when really understood is the province of every human being."

Henri's teaching philosophy emphasized individuality, vitality, and the idea that art should be an expression of life. He urged students to work quickly and intuitively, to capture the essence of a subject rather than getting bogged down in superficial details. He encouraged them to study the masters not to imitate them, but to understand the principles behind their greatness. His influence extended to a remarkably diverse group of prominent American artists who passed through his classes. Among his many notable students were George Bellows, Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Stuart Davis, Guy Pène du Bois, Leon Kroll, Morgan Russell, and Patrick Henry Bruce. While these artists developed vastly different styles, many credited Henri with instilling in them a sense of purpose and a commitment to artistic integrity.

The Art Spirit: A Legacy in Print

Henri's influence as a teacher was codified and extended through his book, The Art Spirit. Published in 1923, the book was compiled by former student Margery Ryerson from Henri's extensive notes, articles, lectures, and critiques delivered over his years of teaching. It is not a technical manual but rather a collection of aphorisms, anecdotes, and philosophical reflections on the meaning and practice of art. The Art Spirit encapsulates Henri's core beliefs: the importance of self-discovery, the connection between art and life, the need for artists to be engaged with their time and place, and the idea that the goal of art is to stimulate, awaken, and intensify the viewer's sense of existence.

The book champions sincerity, individuality, and courage in artistic expression. Henri advises artists to "be yourself," to find subjects that genuinely move them, and to develop techniques that serve their personal vision. He discusses the importance of observation, memory, and imagination, and the need to maintain a spirit of experimentation. The Art Spirit quickly became, and remains, a classic text for art students and artists. Its accessible style and inspirational message have resonated with generations, offering encouragement and practical wisdom. Its enduring popularity testifies to the power and relevance of Henri's humanistic approach to art-making and appreciation.

Artistic Style and Technique

Robert Henri's mature style is characterized by its directness, energy, and focus on capturing the essential character of his subjects. While influenced by Impressionism in his early career, particularly in his landscape work and attention to light, he moved towards a more solid, realist approach often employing a darker palette reminiscent of Manet, Hals, and Velázquez. His brushwork is typically vigorous and visible, applied with a sense of immediacy, often using alla prima (wet-on-wet) techniques to capture fleeting expressions or moments. He believed the paint itself, its texture and application, should contribute to the work's expressive power.

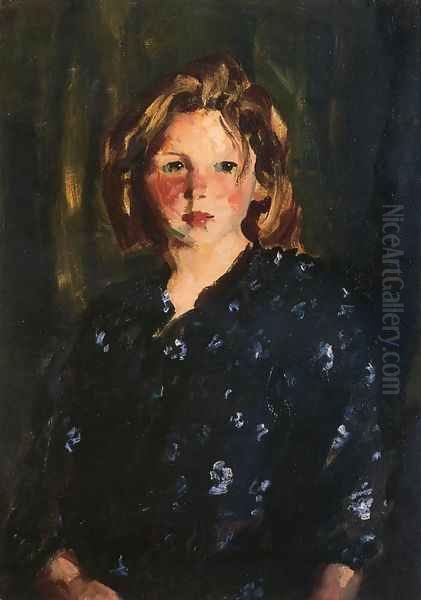

Henri was particularly renowned as a portrait painter. He painted people from all walks of life – society figures, fellow artists, immigrants, Native Americans, African Americans, and especially children. He had an extraordinary ability to capture not just a likeness, but the personality and inner vitality of his sitters. His portraits, such as Laughing Child (1907) or Eva Green (1907), are notable for their psychological insight and lack of sentimentality. He often used dark, dramatic backgrounds to throw the figure into sharp relief, focusing attention on the face and expression. His urban scenes, like the iconic Snow in New York (1902), convey the atmosphere and energy of the city with bold compositions and expressive handling of paint.

Travels and Expanding Horizons

While deeply associated with New York City, Henri traveled extensively throughout his life, and these experiences enriched his art. He made numerous trips back to Europe, revisiting France and Spain. Spain held a particular fascination for him, partly due to his admiration for Velázquez. He painted bullfights, dancers like the subject of his famous Salome Dancer (1909), and portraits of Spanish locals, often employing a darker, more dramatic palette inspired by Spanish masters.

Later in his career, starting in 1913, Henri began spending summers on Achill Island, off the coast of County Mayo in Ireland. He was captivated by the rugged landscape and the character of the local people, particularly the children. He painted numerous portraits of Irish villagers, capturing their resilience, dignity, and connection to their environment. These Irish portraits, often featuring rosy-cheeked children with direct gazes, are among his most beloved works. They demonstrate his consistent ability to find compelling subjects outside the conventional bounds of academic art and to portray them with empathy and respect. His travels provided fresh perspectives and subject matter, reinforcing his belief that art could be found everywhere. He also spent time painting in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1916, 1917, and 1922, encouraging other artists like Leon Kroll and George Bellows to visit, thus influencing the development of the Santa Fe art colony.

Key Works and Subject Matter

Robert Henri's oeuvre is substantial and varied, but certain works stand out as particularly representative of his style and concerns. His urban landscapes, such as Snow in New York (1902), capture the specific atmosphere of the city with a realism that was novel for its time, finding beauty in everyday weather conditions and street scenes. Street Corner in Paris (1899) reflects his earlier engagement with European city life, showing an observational acuity he would later apply to New York.

His portraits are perhaps his most celebrated contributions. Laughing Child (1907) exemplifies his ability to capture spontaneous joy and vitality, using energetic brushwork. Salome Dancer (1909), inspired by contemporary interest in modern dance and perhaps Maud Allan's controversial performances, is a dynamic full-length portrait showcasing his bolder color and expressive handling. His portraits of diverse ethnic types, including Native Americans (like Jim Riley, 1917), Spanish gypsies, and Irish villagers (like Himself and Herself, depicting local Achill Islanders), demonstrate his broad human interest and his skill in conveying individual character and dignity regardless of social standing. These works embody his philosophy of finding art in the real lives of ordinary and extraordinary people.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

Robert Henri remained an active painter and influential teacher well into the 1920s. He continued to exhibit his work and advocate for artistic independence. Although the rise of European avant-garde movements, showcased dramatically at the 1913 Armory Show, began to shift the focus of American modernism towards abstraction, Henri's brand of realism remained a powerful force. He was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1906, despite his earlier conflicts with it, indicating his eventual acceptance by the establishment he had once challenged. However, he remained committed to his core principles of artistic freedom and the importance of depicting contemporary life.

In his later years, Henri suffered from ill health. He was diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. He died in New York City on July 12, 1929, at the age of 64. His death was mourned as the loss of a major figure in American art – a painter, a leader, and an inspirational teacher. His influence extended far beyond the Ashcan School; his emphasis on personal expression and finding art in American life resonated through subsequent generations. Artists like Edward Hopper, though developing a very different style, carried forward Henri's focus on the realities and psychological nuances of American experience.

Conclusion: An American Master

Robert Henri's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he created a powerful body of work, particularly in portraiture, that captured the spirit of his time and place with honesty and vitality. As a leader, he spearheaded the Ashcan School and "The Eight," challenging the conservative art establishment and championing a distinctly American realism focused on contemporary urban life. As an educator, his impact was immense, inspiring countless students through his teaching and through his enduring book, The Art Spirit. He played a pivotal role in the transition of American art into the modern era, advocating for artistic freedom, personal vision, and the profound connection between art and life. Robert Henri remains a crucial figure for understanding the development of American art in the twentieth century, a true American master who helped forge a path for artists seeking to express the realities of their own world.