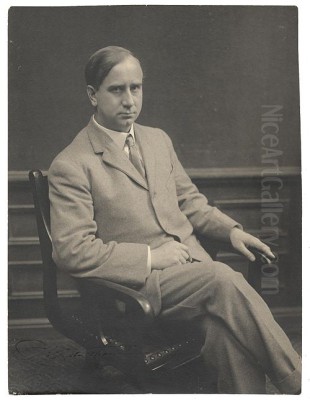

Charles Webster Hawthorne stands as a pivotal figure in American art history, celebrated not only for his evocative paintings but also for his profound impact as an educator. Active during a transformative period in American art, Hawthorne skillfully navigated the currents of Impressionism and Realism, forging a unique style characterized by vibrant color, strong composition, and deep human empathy. His founding of the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts, cemented his legacy, influencing generations of artists. This exploration delves into the life, work, teaching, and enduring significance of a painter who captured the essence of American life, particularly the rugged character of coastal New England.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Charles Webster Hawthorne was born on January 8, 1872, in Lodi, Illinois. His early life, however, was shaped by the maritime environment of Richmond, Maine, where his family relocated. His father, a sea captain, instilled in the young Hawthorne a familiarity and fascination with the sea and those whose lives were intertwined with it – themes that would resonate throughout his artistic career. This coastal upbringing provided a foundational connection to the subjects he would later portray with such insight and sensitivity in his mature work.

Seeking to pursue his artistic ambitions, Hawthorne moved to New York City around the age of 18, near 1890. Life in the metropolis required resourcefulness; he supported himself by working during the day, initially as an office boy and later in a stained-glass factory. His evenings were dedicated to honing his craft. He enrolled in classes at the Art Students League, a crucial hub for aspiring artists. There, and through private study, he came under the tutelage of influential figures who would shape his early development.

Among his most significant teachers were Henry Siddons Mowbray, known for his allegorical murals and easel paintings, and, most importantly, William Merritt Chase. Chase, a preeminent American Impressionist and a charismatic teacher, recognized Hawthorne's talent. Hawthorne studied with Chase at his Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art on Long Island, eventually becoming his assistant. Chase's emphasis on alla prima (wet-on-wet) painting, bravura brushwork, and capturing the fleeting effects of light profoundly influenced Hawthorne. However, Hawthorne would eventually synthesize these lessons into his own distinct artistic voice.

To further broaden his artistic horizons, Hawthorne embarked on studies abroad. He traveled to the Netherlands, where he immersed himself in the works of the Dutch Masters, particularly Frans Hals. Hals's dynamic brushwork, psychological acuity in portraiture, and ability to capture character with seeming effortlessness left an indelible mark on Hawthorne. He also spent time in Italy, absorbing the lessons of Renaissance masters like Titian, whose command of color and composition was legendary, and potentially encountering the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and the poetic moods of Giorgione. This European exposure enriched his technical skills and deepened his understanding of art history, providing a broader context for his developing American perspective.

The Provincetown Art Colony and the Cape Cod School of Art

Upon returning from Europe, Hawthorne sought a location to establish his own artistic practice and, crucially, a school based on his evolving principles. In 1899, he founded the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts. This decision proved transformative, not only for Hawthorne's career but also for the cultural landscape of Provincetown itself. Located at the very tip of Cape Cod, Provincetown offered unique qualities: dramatic coastal scenery, luminous light reflected by sand and sea, and a diverse community, including a significant population of Portuguese fishermen and their families.

The Cape Cod School of Art quickly gained renown, attracting students from across the country. It was one of the first major summer schools in America dedicated primarily to outdoor figure painting. Hawthorne's presence acted as a magnet, drawing other artists to the area and solidifying Provincetown's reputation as a burgeoning art colony, a status it retains to this day. The school operated for over thirty years under his direction, becoming a cornerstone of American art education during the early 20th century.

Hawthorne's vision for the school was rooted in direct observation and the expressive power of color. He moved away from the traditional academic emphasis on drawing and meticulous rendering, instead encouraging students to see and paint in terms of broad color masses or "spots." His teaching took place primarily outdoors, using the local environment and populace as subjects. This approach fostered a sense of immediacy and required students to grapple directly with the challenges of capturing light, form, and atmosphere in the open air.

The school became a vibrant center of artistic activity. Fellow artists established studios nearby, contributing to a lively exchange of ideas. Figures like Max Bohn and E. Ambrose Webster were part of the Provincetown scene during Hawthorne's time, contributing to the colony's diverse artistic fabric. The school's success demonstrated the appeal of Hawthorne's teaching methods and the unique allure of Provincetown as a place for artistic creation.

Hawthorne's Teaching Philosophy and Methods

Charles Hawthorne was more than just a skilled painter; he was a gifted and influential teacher whose pedagogical approach left a lasting impact. While deeply indebted to his mentor William Merritt Chase, Hawthorne developed a distinct teaching philosophy centered on the primacy of color relationships and the simplification of form. He famously encouraged his students to "Paint! Paint! And leave the rest to the gods!" emphasizing intuition and direct response over laborious preliminary drawing.

His core method involved teaching students to see the subject as a series of interconnected color spots or masses, rather than outlines filled with color. He advocated for outdoor painting ("plein air"), believing that only by working directly from nature could one truly capture the effects of light and atmosphere. Critiques were often conducted outdoors, with Hawthorne analyzing student work in the very environment it was created. He stressed the importance of comparing color notes accurately, understanding how adjacent colors influence each other, and simplifying complex forms into their essential shapes.

A key tenet of his teaching was the concept of light and shadow as distinct masses. He urged students, particularly when painting figures outdoors under strong sunlight, to treat the light-struck areas and the shadow areas as separate, clearly defined shapes of color. He believed that "Anything under the sun is beautiful if you have the vision – it is the seeing of the thing that makes it so." This involved looking for the "beauty of contrast" between large, simple areas of color, value, and temperature. He often had students use a palette knife, which encouraged broad application of paint and discouraged fussy detail.

His teaching was known for its directness and practicality. He focused on solving concrete visual problems. Many of his insights and critiques were recorded by students and later compiled by his wife, Marion Campbell Hawthorne, into the influential book Hawthorne on Painting (published posthumously in 1938). This volume preserved his core ideas, such as "The mechanics of putting one spot of color next to another – the fundamental thing," and "Beauty in art is the delicious notes of color one against the other." The book became a staple for art students, disseminating his methods far beyond those who studied with him directly.

Hawthorne's students included a diverse group of artists who went on to achieve recognition in various fields. Among them were the acclaimed watercolorist John Whorf, the modernist painter Edwin Dickinson (though Dickinson developed a very different style), and even Norman Rockwell, who attended briefly early in his career. His influence extended to artists like Richard E. Miller and William H. Johnson, demonstrating the breadth of his impact. His emphasis on strong design, expressive color, and direct observation provided a solid foundation for artists pursuing different stylistic paths.

Artistic Style and Influences

Charles Webster Hawthorne's artistic style is a compelling synthesis of late 19th and early 20th-century currents, primarily American Naturalism and Impressionism, filtered through his unique sensibility and reverence for certain Old Masters. He resisted categorization within a single movement, instead forging a personal approach that prioritized strong characterization, vibrant color, and solid compositional structure.

The influence of William Merritt Chase is evident in Hawthorne's fluid brushwork and interest in capturing the effects of light. However, Hawthorne's figures generally possess a greater sense of weight and psychological depth than typically found in Chase's more purely Impressionistic works. Hawthorne adapted Impressionist techniques – broken color, attention to atmospheric light – but grounded them in a more solid, almost sculptural sense of form, reflecting the Naturalist tradition's focus on objective reality and tangible presence.

His deep admiration for Frans Hals is palpable in his portraiture and figure studies. Like Hals, Hawthorne often employed vigorous, visible brushstrokes to convey vitality and character. He sought to capture the sitter's personality not through minute detail, but through gesture, posture, and the overall impression created by bold planes of color and light. This approach lent his portraits a sense of immediacy and psychological insight.

The influence of other Old Masters, encountered during his European travels, also informed his work. The rich color harmonies and compositional strength seen in paintings by Titian resonated with Hawthorne's own pursuit of powerful visual statements. While not employing the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio or Rembrandt in the same way, his understanding of light and shadow as compositional tools certainly benefited from studying their works. He learned from the masters how to use light not just to describe form, but to create mood and focus attention.

Hawthorne's palette was often rich and vibrant, particularly in his outdoor studies. He excelled at capturing the intense sunlight of Cape Cod, contrasting warm lights with cool, luminous shadows. His indoor portraits, while sometimes more subdued, still relied on carefully observed color relationships to define form and create atmosphere. Works like The White Satin Dress (1915) showcase his ability to handle subtle variations in light and texture, creating a serene yet visually complex image. The painting demonstrates his focus on light effects and the "beauty of contrast" within a relatively controlled setting.

Compared to other American Impressionists like Childe Hassam or John Henry Twachtman, Hawthorne's work often feels more grounded and less purely focused on atmospheric dissolution of form. While Hassam might capture the shimmering light on a flag-draped street, Hawthorne would focus on the sturdy character of a fisherman standing against the bright Provincetown sky. His figures retain their solidity and individuality, reflecting a closer kinship with the Realist tradition exemplified by artists like Thomas Eakins, albeit with a much brighter, more Impressionist-influenced palette.

Themes and Subjects

Hawthorne's choice of subject matter was deeply connected to his environment and his empathetic view of humanity. While he was a capable landscape painter, his primary focus was the human figure, particularly the working-class inhabitants of Provincetown and Cape Cod. He found endless inspiration in the local Portuguese fishing community, drawn to their resilience, dignity, and connection to the sea.

His paintings often depict fishermen, their wives, and children. These are not romanticized or idealized portrayals; rather, they convey a sense of lived experience and quiet strength. Works like The Trousseau (Metropolitan Museum of Art) or The Crew of the Ship Atlantic capture groups with a sense of community and shared purpose. His single-figure portraits, such as the poignant The Widow (1913), delve into individual character and emotion, often conveying themes of endurance, contemplation, or familial bonds. He treated his subjects with profound respect, finding beauty and significance in their everyday lives.

His connection to the sea, likely stemming from his father's profession and his Maine upbringing, remained a constant thread. Fishermen mending nets, boats pulled ashore, figures silhouetted against the vast expanse of the ocean – these motifs recur throughout his oeuvre. He captured the specific light and atmosphere of the Cape Cod coast, making the environment an integral part of his figurative work. The interaction between the figures and their maritime surroundings is central to the power of these paintings.

Hawthorne also produced formal portraits and studies of figures in interiors, demonstrating his versatility. The White Satin Dress, for example, shifts focus to a more domestic, contemplative scene, showcasing his skill in rendering textures and capturing subtle indoor lighting. Yet, even in these works, there is often an underlying sense of gravity and thoughtful observation that connects them to his studies of the Provincetown locals. He consistently sought the essential character of his subjects, whether they were weathered fishermen or young women in quiet repose. His work stands as a testament to the beauty found in ordinary people and the landscapes they inhabit.

Connections and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Charles Webster Hawthorne moved within significant artistic circles, primarily defined by his relationship with his teacher, his own role as an educator, and his central position in the Provincetown art colony. His most formative connection was undoubtedly with William Merritt Chase. Starting as a student and then becoming Chase's assistant provided Hawthorne with invaluable training and exposure. While he eventually forged his own path, the foundational principles learned from Chase regarding direct painting and the importance of light remained influential.

In Provincetown, Hawthorne was a leading figure. His establishment of the Cape Cod School of Art attracted numerous artists, fostering a dynamic community. He interacted with fellow instructors and resident artists like Max Bohn and E. Ambrose Webster, contributing to the colony's growth and reputation. The environment was one of shared purpose, even if artistic styles varied widely. Hawthorne's school became a hub, drawing students who would, in turn, contribute to the American art scene. His student John Whorf, for instance, became a highly regarded watercolorist, carrying forward elements of Hawthorne's emphasis on capturing light and atmosphere.

Hawthorne also participated in the broader art world through exhibitions. His inclusion in a 1903 exhibition in Barcelona alongside artists like Ernesto Ullmann indicates his growing reputation beyond American shores early in his career. He regularly exhibited in major national shows, such as those at the National Academy of Design (to which he was elected an Associate in 1908 and a full Academician in 1911), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Carnegie Institute. These exhibitions placed his work in dialogue with that of other leading American artists of the day.

While his style differed significantly from the urban realism of the Ashcan School painters like Robert Henri or George Bellows, Hawthorne shared their interest in depicting contemporary American life with honesty and vigor. Unlike the more experimental paths being forged by early modernists associated with Alfred Stieglitz's circle, Hawthorne remained committed to representational painting, albeit infused with Impressionist color and light. His position was unique – a modern traditionalist who absorbed contemporary influences while retaining a strong connection to classical principles and direct observation, influencing generations through his Provincetown school.

Legacy and Recognition

Charles Webster Hawthorne died relatively young, on November 29, 1930, but his legacy was already firmly established. His contributions endure through his powerful body of artwork and his profound influence as an educator. He is recognized as a major figure in American Impressionism and Realism, particularly noted for his sensitive portrayals of the people of Cape Cod and his mastery of color and light.

His paintings are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, among others. His work continues to be studied and admired for its technical skill, compositional strength, and emotional resonance. He received numerous awards during his lifetime, including medals from prestigious exhibitions, affirming his standing among his peers.

Perhaps his most lasting legacy lies in his role as a teacher. The Cape Cod School of Art, under his direction for over three decades, shaped the development of countless artists. His teaching methods, emphasizing direct observation, the simplification of form into color masses, and outdoor painting, offered a vital alternative to more rigid academic approaches. The publication of Hawthorne on Painting ensured that his core ideas reached an even wider audience and continue to be consulted by art students today. He instilled in his students a way of seeing – focusing on relationships, color harmony, and capturing the essential character of the subject.

Hawthorne's influence extended to the development of Provincetown as a major American art colony. His presence and the success of his school were instrumental in attracting other artists and establishing the town's enduring identity as a center for creative expression. He helped define a regional school of painting focused on the unique light and life of outer Cape Cod.

In the broader narrative of American art, Hawthorne occupies a significant position as a bridge figure. He successfully integrated European influences, particularly Impressionism and the techniques of Old Masters like Hals, into a distinctly American context. He championed representational painting grounded in observation during a period when abstraction was beginning to emerge, yet his approach was fresh and modern in its emphasis on color and directness. Charles Webster Hawthorne remains a respected master, admired for his artistic integrity, his empathetic depictions of American life, and his enduring contribution to art education.

Conclusion

Charles Webster Hawthorne carved a unique and influential path through American art in the early 20th century. As both a painter and a teacher, he emphasized the importance of direct observation, the expressive power of color, and the inherent dignity of the human subject. From his early studies with William Merritt Chase and his immersion in the works of European masters to his founding of the seminal Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Hawthorne dedicated his life to capturing the visual world with honesty and vitality. His paintings, particularly his portraits of the Provincetown fishing community, stand as powerful testaments to his skill and empathy. Through his art and his teaching, Hawthorne fostered a way of seeing that valued strong design, vibrant color relationships, and the essential character of form, leaving an indelible mark on generations of American artists and securing his place as a key figure in the nation's artistic heritage.