Philip Leslie Hale (1865-1931) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes complex, figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter, influential educator, and prolific writer, Hale was deeply embedded in the Boston art scene, contributing to its vibrancy and its engagement with international artistic currents, particularly French Impressionism. His career reflects a dynamic interplay between tradition and modernity, a journey marked by periods of avant-garde experimentation and a later return to more conservative, academic principles. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, key works, and his lasting impact on American art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1865, Philip Leslie Hale hailed from a distinguished New England family steeped in intellectual and literary traditions. He was the son of the prominent Unitarian minister, author, and abolitionist Reverend Edward Everett Hale, and a grandnephew of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the celebrated author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin." This environment of cultural and social engagement undoubtedly shaped young Philip's worldview, though his path would lead him away from the literary and theological pursuits of his forebears and towards the visual arts.

Despite his intellectual upbringing and successfully passing the entrance examinations for Harvard University, Hale felt a stronger calling. Encouraged by his family, he made the pivotal decision to forgo a traditional academic path at Harvard and instead dedicate himself to the pursuit of an artistic career. This choice set him on a course that would see him become a key proponent of Impressionism in America and a respected voice in art education and criticism.

Formative Training: Boston and New York

Hale's formal artistic training began in his native Boston at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Here, he studied under Edmund C. Tarbell, who would become a leading figure of the Boston School of painters, known for their refined Impressionistic depictions of genteel domesticity and elegant portraiture. Another instructor mentioned in connection with his early studies was Olden Wilder, though Tarbell's influence was particularly formative during this period. The Boston Museum School, at this time, was fostering a generation of artists who, while rooted in academic tradition, were increasingly open to the fresh perspectives offered by European modernism.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Hale moved to New York City to continue his studies at the Art Students League. This institution was a crucible for emerging American artists, offering a more liberal alternative to the National Academy of Design. At the League, Hale studied under notable figures such as J. Alden Weir, himself an important American Impressionist, and Kenyon Cox, a respected muralist and advocate for academic classicism. This exposure to different artistic philosophies—the burgeoning Impressionism of Weir and the academic rigor of Cox—provided Hale with a diverse foundation upon which to build his own artistic identity.

The Parisian Experience: Impressionism and Beyond

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Hale recognized the necessity of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the revolutionary movements unfolding in Paris. He traveled to France, immersing himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of the French capital. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art, and also attended the Académie Julian, a popular private art school that attracted a large international student body and offered a more flexible curriculum. At these institutions, he would have encountered the teachings of academic masters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, and Gustave Boulanger, who trained many American artists.

A pivotal part of Hale's European sojourn was his time spent in Giverny, the small village northwest of Paris that had become synonymous with Claude Monet, the master of French Impressionism. Hale spent summers in Giverny, often in the company of his friend, the American artist Theodore Earl Butler, who would later marry Monet's stepdaughter, Suzanne Hoschedé. In Giverny, Hale had the invaluable opportunity to absorb the principles of Impressionism directly, observing Monet's revolutionary approach to light, color, and plein air painting. This experience profoundly influenced Hale's artistic direction, steering him towards a more experimental and avant-garde style.

During his time in Europe, Hale also dedicated himself to studying the Old Masters, diligently copying works by artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Johannes Vermeer, Jean-Antoine Watteau, and Michelangelo in major museums. This practice of copying was a traditional method of artistic education, allowing artists to intimately understand composition, technique, and form. Hale's engagement with both the radical innovations of Impressionism and the enduring principles of classical art reflects the complex artistic currents of the late 19th century. He lived a somewhat bohemian lifestyle in Paris, fully embracing the artistic ferment of the era.

Return to Boston: A Multifaceted Career

Upon his return to the United States, Philip Leslie Hale embarked on a multifaceted career that established him as a prominent figure in the American art world, particularly in Boston. He was not only a dedicated painter but also a highly influential educator and a respected, if sometimes controversial, art critic and writer.

The Painter: Evolving Styles and Subjects

As a painter, Hale became known for his Impressionistic style, particularly his decorative depictions of female figures, often bathed in sunlight, and his evocative landscapes. His early work, heavily influenced by his time in France, showed a clear affinity with the techniques of Claude Monet and the aesthetic sensibilities of the French avant-garde group Les Nabis, which included artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, known for their emphasis on color, pattern, and subjective interpretation. Hale's paintings from this period often feature broken brushwork, a vibrant palette, and a keen interest in capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. He demonstrated a particular skill in rendering the interplay of sunlight and shadow, creating compositions that were both visually stimulating and emotionally resonant.

His subject matter frequently revolved around women, often portrayed in leisurely outdoor settings or in intimate domestic interiors. These works, while Impressionistic in technique, also sometimes carried Symbolist undertones, hinting at deeper psychological or emotional states. Works like Girls in Sunlight (1895) exemplify his early Impressionist phase, capturing youthful figures in a sun-dappled environment with a sense of immediacy and vibrancy.

Later in his career, Hale's style underwent a noticeable shift. While he never entirely abandoned his Impressionistic roots, his work began to exhibit a greater emphasis on academic structure, draftsmanship, and a more conservative approach to form and composition. This evolution may have reflected his deep engagement with art history and his teaching responsibilities, which required a thorough understanding of traditional artistic principles. Despite this shift, his sensitivity to color and light remained a hallmark of his work.

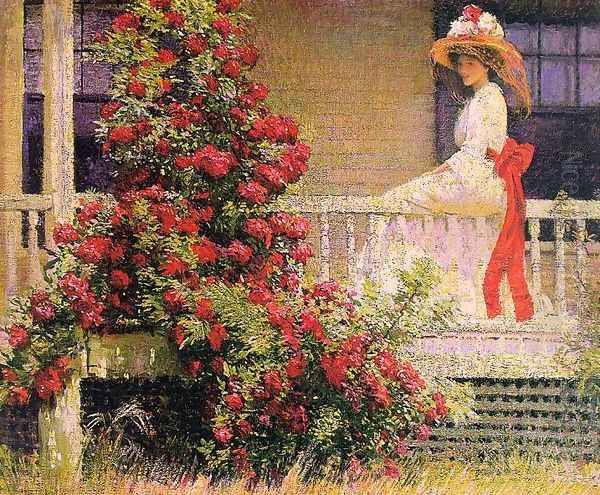

Among his most celebrated paintings is The Crimson Rambler (1908). This work, depicting a woman in a white dress standing before a profusion of crimson rambler roses, is a quintessential example of American Impressionism, showcasing Hale's mastery of color, light, and decorative composition. The painting was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where it received considerable acclaim. Other notable works include The Rose Tree Girl, Sarah Bernhardt as the Distant Princess (likely a reference to her role in Edmond Rostand's "La Princesse Lointaine"), and The Gypsy Guitarist, each demonstrating his versatility in subject and his ability to capture character and mood.

The Educator: Shaping a Generation

Philip Leslie Hale's impact as an educator was profound and far-reaching. He began teaching at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, his alma mater, in 1893, and eventually became its chief instructor of drawing and lecturer on artistic anatomy and art history. His teaching was characterized by a rigorous approach to draftsmanship and a deep knowledge of art history, combined with an understanding of modern artistic developments. He was known for his articulate lectures and his ability to inspire his students.

Beyond the Boston Museum School, Hale also held teaching positions at other prestigious institutions, including the Worcester Art Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He is also noted as having taught at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Through his long and dedicated teaching career, Hale influenced a generation of American artists, imparting to them both technical skill and a broad appreciation for the complexities of art. Among his many students was Mary Bradish Titcomb, who also became a noted artist and with whom he sometimes collaborated. His pedagogical approach, which balanced classical training with an awareness of contemporary trends, helped to shape the direction of art education in America.

The Writer and Critic: A Voice in Art Discourse

Complementing his work as a painter and teacher, Philip Leslie Hale was a prolific writer and art critic. He contributed art criticism and articles to several prominent publications, including the Boston Post and the Boston Globe. His writing was often characterized by strong opinions and a sophisticated understanding of art theory and history. He was not afraid to engage in critical debate and played an active role in shaping public discourse about art in Boston and beyond.

Hale also authored several books on art and art history, further solidifying his reputation as a scholar and an authority in the field. One of his notable publications was "Jan Vermeer of Delft" (1913), a significant early monograph on the Dutch master, which contributed to the revival of interest in Vermeer's work in the early 20th century. He also wrote a column titled "Art in Paris" for Arcadia magazine, sharing his insights on the European art scene with an American audience. His writings provided valuable commentary on contemporary art movements and helped to educate the public about artistic principles and historical developments.

Artistic Style and Influences: A Deeper Look

Philip Leslie Hale's artistic style is most closely associated with American Impressionism, particularly the Boston School, which included figures like his former teacher Edmund Tarbell, Frank Weston Benson, Joseph DeCamp, and William McGregor Paxton. These artists adapted French Impressionist techniques to American subjects, often focusing on elegant figures in sunlit interiors or idyllic landscapes. Hale's work shares the Boston School's emphasis on refined aesthetics, skilled draftsmanship, and the depiction of light.

His early exposure to Claude Monet in Giverny was undoubtedly a primary influence, evident in his broken brushwork, his attention to the transient effects of light, and his vibrant color palette. He was also drawn to the work of Edgar Degas, whose innovative compositions and focus on contemporary life resonated with many artists of the period. Furthermore, Hale was influenced by the Post-Impressionist group Les Nabis, whose members, including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis, explored the decorative and expressive potential of color and pattern, often imbuing their works with a sense of intimacy and subjective feeling. Elements of Symbolism can also be detected in some of Hale's works, particularly in their evocative moods and suggestive imagery.

While his early career was marked by this engagement with avant-garde European art, Hale's later work saw a partial return to more academic concerns. This shift might be seen as a reflection of his deep respect for the traditions of Western art, which he studied and taught extensively. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, with his emphasis on tonal harmonies and aestheticism, also likely played a role in shaping Hale's artistic vision, particularly in his more atmospheric and subtly colored compositions. His commitment to drawing and anatomical accuracy, honed through his teaching, remained a constant throughout his career, providing a solid structural foundation even in his most Impressionistic paintings.

Key Works in Detail

Several of Philip Leslie Hale's paintings stand out as representative of his artistic achievements and his contribution to American Impressionism.

Girls in Sunlight (1895): This early work captures the essence of Hale's Impressionistic style. It depicts young women in a bright, sun-drenched outdoor setting. The painting is characterized by its luminous color, energetic brushwork, and the skillful rendering of dappled sunlight filtering through foliage. It conveys a sense of spontaneity and the fleeting beauty of a summer day, hallmarks of the Impressionist movement.

The Crimson Rambler (1908): Perhaps Hale's most famous painting, The Crimson Rambler is a masterful example of American Impressionism. The work features a gracefully posed woman in a flowing white dress, standing before a vibrant cascade of crimson rambler roses. Hale's handling of light is particularly noteworthy, as sunlight illuminates the figure and the brilliant red blossoms, creating a dazzling visual effect. The composition is both elegant and decorative, reflecting the aesthetic ideals of the Boston School. The painting's success at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts exhibition underscored Hale's prominence in the American art scene.

The Rose Tree Girl: Similar in theme and style to The Crimson Rambler, this painting likely features a female figure in a garden setting, emphasizing the harmony between humanity and nature. Hale's skill in depicting floral elements and the interplay of light and color would have been central to this work, creating a scene of tranquil beauty.

These works, among others, demonstrate Hale's ability to synthesize Impressionist techniques with a distinctly American sensibility, creating paintings that are both visually captivating and emotionally engaging.

Contemporaries and the Boston School

Philip Leslie Hale was an integral part of a vibrant artistic community. His connection to the Boston School of painters was central to his career. This group, which included his teacher Edmund Tarbell, as well as Frank Weston Benson, Joseph DeCamp, and William McGregor Paxton, shared a common artistic language rooted in academic training but enlivened by Impressionist principles. They often depicted scenes of refined domesticity, elegant portraiture, and sunlit landscapes, creating an art that celebrated beauty and genteel living.

Beyond the Boston School, Hale interacted with a wide range of American Impressionists, such as Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman, who were also adapting French Impressionism to American themes and landscapes. His studies in New York brought him into contact with J. Alden Weir and Kenyon Cox. His time in Paris connected him with Theodore Earl Butler and, most significantly, Claude Monet. The influence of French artists like Edgar Degas and the Nabis group (Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis) further shaped his artistic development. His sister, Ellen Day Hale, was also a respected artist, and his wife, Lilian Westcott Hale, was a highly accomplished painter in her own right, known for her delicate charcoal drawings and sensitive portraits. This network of artistic relationships provided a rich context for Hale's own work and development. He was also a member of several art clubs, including the Boston Art Club, the St. Botolph Club, and the Philadelphia Art Club, which facilitated further interaction with his peers.

Personal Life and Collaborations

Philip Leslie Hale's personal life was closely intertwined with his artistic career. He came from a family that, while not primarily artistic, valued cultural pursuits. His decision to pursue art was supported, and his intellectual background informed his approach to his work.

An interesting episode from his earlier life involved a planned engagement to the artist Ethel Reed, a notable poster designer of the 1890s. However, this engagement did not culminate in marriage. Instead, Hale married Lilian Westcott Hale (1880–1963) in 1902. Lilian was a talented artist herself, and the two shared a deep personal and professional connection. They even rented adjoining studios, indicative of their shared commitment to their artistic practices. Lilian Westcott Hale gained recognition for her sensitive charcoal portraits, pastels, and oil paintings, often depicting women and children with a delicate, ethereal quality. Their partnership was one of mutual artistic support and influence. Together, Philip and Lilian had one daughter, Nancy Hale (1908–1988), who became a well-known novelist and short-story writer, continuing the family's literary legacy.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Philip Leslie Hale's work was exhibited regularly throughout his career, contributing to his reputation as a leading American Impressionist. A significant early milestone was his first solo exhibition, held in 1899 at the prestigious Durand-Ruel Galleries in New York City. This gallery was instrumental in introducing French Impressionism to American audiences, so a show there was a notable achievement for an American artist working in an Impressionist vein. The exhibition featured his Impressionist paintings and watercolors and reportedly received mixed, though generally positive, reviews.

His work was also shown at major institutions such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where The Crimson Rambler garnered significant praise. In 1924, his works were first exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the leading art institution in his home city and where he had a long teaching career. This marked an important recognition of his contributions.

The provided information also mentions that retrospective exhibitions of his work were held at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1966 and 1988. Such posthumous exhibitions serve to re-evaluate and celebrate an artist's oeuvre, ensuring their legacy endures for new generations. His paintings are held in the collections of numerous museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, attesting to his lasting significance in American art.

Legacy

Philip Leslie Hale left a multifaceted legacy as an artist, educator, and writer. As a painter, he was a key figure in the American Impressionist movement, particularly associated with the Boston School. His works are admired for their technical skill, their sensitive depiction of light and color, and their elegant portrayal of American life at the turn of the century. While his style evolved, his commitment to capturing beauty and his sophisticated understanding of artistic principles remained constant.

As an educator, Hale's influence was profound. Through his long tenure at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and his teaching at other institutions, he shaped the artistic development of countless students. His emphasis on rigorous draftsmanship, anatomical knowledge, and art historical understanding provided a strong foundation for aspiring artists.

As a writer and critic, Hale contributed to the intellectual discourse surrounding art in America. His articles and books helped to educate the public and articulate critical perspectives on both historical and contemporary art. His scholarship, particularly his work on Vermeer, demonstrated his deep engagement with art history.

Conclusion

Philip Leslie Hale's career was a testament to a life deeply immersed in the world of art. From his early embrace of Impressionism, influenced by his experiences in Giverny and his association with Claude Monet, to his later, more academically informed style, Hale navigated the complex artistic currents of his time with intelligence and skill. His contributions as a painter of luminous and evocative scenes, a dedicated and influential teacher, and an articulate writer and critic solidify his place as an important figure in the history of American art. His work continues to be appreciated for its beauty, craftsmanship, and its reflection of a pivotal era in American cultural development, bridging the traditions of the 19th century with the emerging modernism of the 20th.