Robert Henry Logan (1874-1942) stands as a distinctive figure within the narrative of American Impressionism. An artist known for his technical skill, sensitivity to light, and a notably private demeanor, Logan navigated the transatlantic currents of art at the turn of the twentieth century. Trained in the burgeoning Impressionist-influenced environment of Boston before immersing himself in the artistic crucible of Paris, he achieved recognition abroad only to later retreat from the conventional path of a painter, dedicating his final years to different forms of craftsmanship. His life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the choices and trajectory of an American artist shaped by both native traditions and European innovations.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Boston

Robert Henry Logan was born on June 24, 1874, in Waltham, Massachusetts. His origins were modest; he hailed from a working-class family, with his father employed as a worker in one of the town's prominent watch factories. This background set him apart from some of his contemporaries who came from more privileged circumstances, perhaps instilling in him a sense of reserve that would characterize his later life. Despite these beginnings, Logan demonstrated an early aptitude and inclination towards art, leading him to seek formal training in the vibrant artistic hub of nearby Boston.

His artistic education took place at the prestigious School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (SMFA). This was a pivotal period, as the school was then a center for what became known as the Boston School of painting. Logan had the distinct advantage of studying under two of its leading figures: Frank W. Benson (1862-1951) and Edmund C. Tarbell (1862-1938). Both Benson and Tarbell were highly respected painters and influential teachers who had absorbed the lessons of French Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments, while retaining a strong foundation in academic draftsmanship and traditional composition.

Studying under Benson and Tarbell provided Logan with a rigorous grounding in technique combined with an exposure to modern, Impressionist-influenced aesthetics. The Boston School itself was known for its elegant depictions of genteel life, often featuring women in interiors illuminated by natural light, as well as plein-air landscapes. Logan absorbed these influences, developing a refined technique and a keen eye for the subtleties of light and atmosphere. This Boston training formed the bedrock of his artistic practice, even as he sought further experience abroad.

Parisian Immersion and European Influences

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Logan recognized the necessity of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the developments unfolding in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. In 1895, he made the journey across the Atlantic, enrolling in the Académie Julian. This famous private art school attracted students from around the globe, offering an alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. It was known for its roster of respected, if somewhat conservative, academic painters who served as instructors.

In Paris, Logan expanded his artistic horizons under the tutelage of figures associated with the French academic tradition, yet who also operated within the broader, dynamic Parisian art scene. His teachers reportedly included Louis Joseph Raphael Collin (1850-1916), known for his idealized nudes and decorative works; Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), a history painter working in the academic style; and Benjamin Constant (1845-1902), famed for his Orientalist subjects and portraiture. Exposure to these masters would have further honed his technical skills in drawing and composition.

Beyond the formal academy setting, the atmosphere of Paris itself was an education. Logan arrived at a time when Impressionism had become an established, though still debated, force, and Post-Impressionist movements were gaining ground. He would have had opportunities to see the works of Impressionist masters like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), as well as the more experimental art of figures like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). While direct influence from the Post-Impressionists isn't strongly evident in his known work, the ambient energy of artistic innovation undoubtedly left its mark.

During his time in Europe, Logan also formed connections with fellow artists. He reportedly studied or interacted with Robert Henri (1865-1929), a pivotal figure in American art who encouraged a more realistic and vigorous approach, though Henri's primary influence would later manifest in the Ashcan School. Logan also developed a friendship with the Canadian painter James Wilson Morrice (1865-1924), another North American artist drawn to the allure of Paris. Morrice, known for his subtly toned landscapes, traveled and exhibited with Logan, suggesting a shared sensibility and mutual artistic respect during these formative European years.

Recognition Abroad: The Paris Salon and Beyond

Logan's period of study and work in Europe culminated in significant professional recognition. A major milestone for any artist in Paris was acceptance into the annual Salon exhibition. In 1905, Logan achieved this distinction, exhibiting his work at the prestigious Salon de la Société des Artistes Français. This was a considerable accomplishment for an American artist, signifying that his work met the standards of the Parisian art establishment and placing him in the company of leading international artists.

Sources also mention that Logan was honored by French and potentially Spanish academies, further testament to the positive reception his work received in Europe. While specifics about a "Prix de Rome" mentioned in some accounts are unclear – whether it was the coveted Grand Prix de Rome (typically for French citizens) or another award – the fact that he received accolades underscores his success during this period. Being recognized by established European institutions was a mark of high achievement and would have boosted his reputation both abroad and potentially back in the United States.

This European success validated Logan's talent and the path he had chosen. He had successfully synthesized his Boston training with the lessons learned in Paris, creating work that resonated with contemporary European tastes while retaining a distinct quality. He was among a select group of American artists who managed to gain a foothold and earn respect within the competitive European art world before deciding to return home.

Logan's Impressionist Style and Representative Works

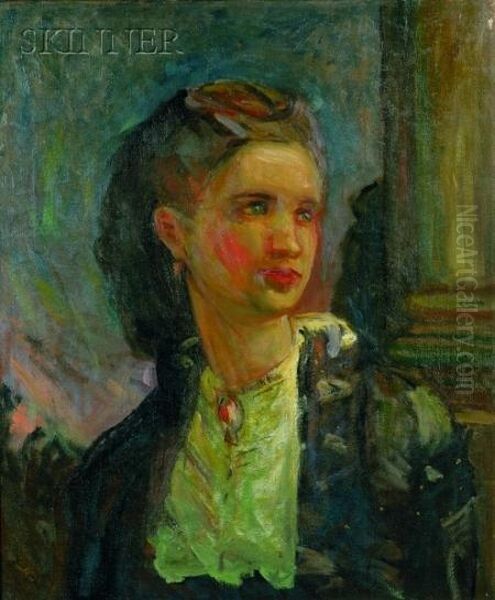

Robert Henry Logan's artistic style is firmly rooted in American Impressionism, reflecting both his Boston School training and his absorption of French Impressionist principles. His work is characterized by a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, often rendered with delicate, broken brushwork that captures the shimmer of light on surfaces and the nuances of color in shadow. While embracing the Impressionist palette and focus on fleeting effects, his work often retained a sense of underlying structure and solid draftsmanship inherited from his academic training under Benson and Tarbell.

His subject matter typically included landscapes, figurative works, and interiors. He excelled at capturing the tranquil beauty of the New England landscape, depicting scenes bathed in the soft light of spring or the warm glow of autumn. His interior scenes often feature figures, frequently women, engaged in quiet domestic activities like sewing or reading, illuminated by window light – a theme popular among Boston School painters. These works showcase his ability to handle complex light effects and create intimate, contemplative moods.

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné is lacking and many works may reside in private collections, certain titles surface in auction records and collection databases, giving a sense of his output. Works such as "Spring Landscape," "Woman Sewing by a Window," "The Green Parasol," "Low Tide," and "Portrait of a Young Woman" exemplify his typical subjects and style. These paintings demonstrate his adeptness with color, his skillful rendering of light, and his ability to imbue scenes with a sense of quietude and gentle refinement. Compared to some French Impressionists, his brushwork might appear more controlled, and his compositions more traditionally structured, aligning him with the particular variant of Impressionism practiced by many Americans.

Return to Waltham and Later Artistic Life

In 1910, at the age of 34, Robert Henry Logan made the decision to return to his hometown of Waltham, Massachusetts. He came back an accomplished artist, recognized in Europe and equipped with a sophisticated technique and mature style. His return coincided with a period when American Impressionism was arguably at its height of popularity in the United States, with artists like Childe Hassam (1859-1935), J. Alden Weir (1852-1919), John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), and Willard Metcalf (1858-1925) enjoying considerable success.

Despite the favorable climate for Impressionism and his own credentials, Logan settled into a life marked by increasing privacy and reserve. While he likely continued to paint for some years after his return, he did not aggressively pursue a high-profile career in the American art scene in the way some of his contemporaries did. He seems to have preferred the familiar surroundings of his hometown to the competitive art centers of Boston or New York.

This period saw him continue to explore the themes and style he had developed, likely painting local landscapes and scenes inspired by his immediate environment. His connection to the Boston art world probably continued to some degree, given his training and the proximity, but he largely operated outside its main currents. His reclusive nature meant that his work from this period might be less documented or widely known compared to his European output or the work of more publicly engaged artists.

A Surprising Shift: From Painting to Craft

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Logan's later life was his significant shift away from painting. Around 1927, when he was in his early fifties, Logan largely abandoned the brush and canvas that had been the focus of his artistic life for decades. Instead, he turned his creative energies towards decorative wood carving and ironwork. This was a dramatic departure from the path of a successful Impressionist painter.

The reasons for this change remain somewhat speculative. It could have stemmed from a personal evolution in artistic interests, a desire for a more hands-on, craft-based form of expression, or perhaps even a disillusionment with the changing art world, which was seeing the rise of Modernism – movements that Logan, with his Impressionist background, might have found alienating. Some accounts suggest he held critical views of certain modern art trends. Whatever the motivation, he dedicated himself to these new crafts with apparent passion.

He continued working in wood and iron for the remainder of his life, until his death in 1942. This later phase, though less studied than his painting career, represents a fascinating final chapter. It speaks to a versatility and a willingness to follow a personal creative path, even if it meant diverging from the medium in which he had achieved notable success. It adds another layer to the portrait of Logan as a private individual, guided by his own inclinations rather than external expectations.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Understanding Robert Henry Logan requires placing him within the rich tapestry of artists active during his time. His teachers, Frank W. Benson and Edmund C. Tarbell, were central figures, linking him directly to the Boston School and its particular interpretation of Impressionism. In Paris, his exposure to academic figures like Collin, Laurens, and Constant provided a traditional counterpoint to the pervasive influence of Impressionism, embodied by giants like Monet and Renoir, and the emerging Post-Impressionism of Cézanne and others.

His association with Robert Henri, even if brief or tangential, connects him to another major force in American art education and the burgeoning realist movement. His friendship and travels with James Wilson Morrice highlight the networks that existed among North American artists living abroad.

Back in the United States, Logan was a contemporary of the leading American Impressionists, including the aforementioned Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, John Henry Twachtman, and Willard Metcalf, as well as others like Theodore Robinson (1852-1896), who had close ties to Monet, and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who achieved immense international fame. While Logan's public profile never reached the level of Hassam or Sargent, his work shares the core concerns of American Impressionism: adapting French techniques to American light and subjects, often with a gentler, more lyrical or decorative sensibility. His later withdrawal from painting contrasts sharply with the lifelong dedication to the medium shown by most of these peers.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Robert Henry Logan is recognized today as a skilled and sensitive painter, an early contributor to the American Impressionist movement. His training under key Boston School figures and his successful immersion in the Parisian art world equipped him with a strong technical foundation and a sophisticated understanding of Impressionist aesthetics. He is counted among the pioneering American artists who absorbed European lessons and adapted them to an American context.

His work is appreciated for its technical proficiency, particularly his handling of light and color, and its often quiet, contemplative mood. However, his legacy is somewhat muted compared to more famous contemporaries. This can be attributed to several factors: his inherently private and reclusive nature, his decision to return to Waltham rather than a major art center, and his significant shift away from painting in the last fifteen years of his life. These choices limited his visibility and the overall volume of his painted oeuvre available to later audiences and scholars.

Despite this, his paintings remain sought after by collectors of American Impressionism, and his work is represented in various collections. He occupies a specific niche within art history – an artist who achieved international validation but ultimately chose a more secluded path. His career highlights the diverse trajectories possible within a single artistic movement and underscores the personal factors that shape an artist's life and legacy. Robert Henry Logan remains a figure worthy of attention, representing a blend of academic rigor, Impressionist sensibility, and individualistic choices that defined his unique journey through the art world of his time.