Jean Frédéric Bazille stands as one of the most poignant figures in the narrative of Impressionism. A painter of remarkable talent, vision, and generosity, his life and career were tragically curtailed by his untimely death in the Franco-Prussian War. Though he did not live to see the full flowering of the Impressionist movement or participate in its groundbreaking first exhibition in 1874, Bazille was an indispensable pioneer. His explorations of light and color, his commitment to painting modern life, and his unwavering support for his fellow artists, including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, laid crucial groundwork for the revolutionary art form that would redefine Western painting. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of a painter whose luminous canvases continue to captivate and whose potential remains a subject of wistful speculation.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations in Montpellier

Frédéric Bazille was born on December 6, 1841, in Montpellier, a sun-drenched city in the Hérault department of Southern France. He hailed from a prominent and affluent Protestant family. His father, Gaston Bazille, was a wealthy landowner, agronomist, and later a senator, while his mother, Camille Vialars, also came from a prosperous background. This comfortable upbringing afforded young Frédéric a refined education and exposure to culture, but it also came with certain familial expectations, particularly regarding his future career.

From an early age, Bazille displayed a keen interest in the visual arts. His passion was likely nurtured by the rich artistic heritage of Montpellier and the vibrant landscapes of the Languedoc region. He was particularly drawn to the works of earlier masters, and his family, while supportive of his artistic pursuits as a pastime, initially envisioned a more conventional and secure profession for him. They encouraged him to study medicine, a field deemed respectable and stable.

Bazille dutifully began his medical studies in Montpellier in 1859. However, his artistic ambitions did not wane. He managed to balance his medical coursework with art lessons, studying under the sculptors Baussan and the painter Pothevin. He also frequented the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, where he could admire works by masters such as Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet, artists whose bold use of color and realistic depictions of contemporary life would later resonate in his own work. The museum's collection, rich in both classical and more contemporary pieces, provided a fertile ground for his developing artistic sensibilities.

Despite his commitment to his medical studies, the allure of Paris, the epicenter of the art world, grew irresistible. He recognized that to truly pursue a career as a painter, he needed to be in the capital, immersed in its dynamic artistic environment and learning from its leading figures.

The Parisian Plunge: Medicine and a New Artistic Milieu

In 1862, at the age of twenty-one, Frédéric Bazille moved to Paris, ostensibly to continue his medical studies. This move, however, was dually motivated; Paris offered him the unparalleled opportunity to immerse himself in the art world. While he enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine, his heart was increasingly set on painting. He soon sought out formal art instruction, a crucial step for any aspiring painter of the era.

Later that year, Bazille made a decision that would prove pivotal in his artistic development and personal life: he enrolled in the studio of Charles Gleyre. Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre was a Swiss academic painter whose studio was a popular, if somewhat traditional, training ground for young artists. Gleyre emphasized draftsmanship and classical composition, but his atelier was also known for being less rigidly dogmatic than some other academic institutions, allowing for a degree of individual expression.

It was at Gleyre's studio that Bazille encountered a group of like-minded young painters who would become his closest friends and future collaborators in the Impressionist movement. These included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and the English-born Alfred Sisley. This quartet quickly formed a strong bond, united by their shared dissatisfaction with the conventional academic training offered by Gleyre and their burgeoning interest in new ways of seeing and representing the world. They found Gleyre's emphasis on mythological and historical subjects increasingly out of touch with their desire to capture the realities and sensations of contemporary life.

While Gleyre's traditional approach provided them with foundational skills, it was their discussions, shared experiments, and mutual encouragement that truly shaped their artistic paths. They began to look beyond the studio walls, inspired by the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the plein-air practices of the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny, who advocated painting directly from nature.

Bazille, with his generous nature and financial stability, often became a central figure in this group. He was known for his kindness and willingness to support his often-struggling friends, a trait that would become even more pronounced as their careers developed. The move to Paris and his entry into Gleyre's studio marked the true beginning of Bazille's journey as a painter, placing him at the heart of a nascent artistic revolution.

Forging Friendships and Artistic Directions

The atmosphere within Gleyre's studio was one of both learning and burgeoning rebellion. While Gleyre himself was a respected academician, his students, particularly Bazille, Monet, Renoir, and Sisley, were already looking towards a different artistic horizon. They found common ground in their admiration for artists who were challenging the established norms of the French art world, most notably Gustave Courbet, with his unflinching Realism, and Édouard Manet, whose daring compositions and contemporary subject matter were causing scandals at the official Salon.

Bazille, Monet, Renoir, and Sisley often sketched and painted together, both within the studio and, increasingly, outdoors. They were drawn to the idea of capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere directly from nature, a practice known as "en plein air." This was a departure from the academic tradition of completing finished paintings in the studio based on preliminary sketches. Their early excursions took them to the Forest of Fontainebleau, particularly to the village of Chailly-en-Bière, a favored haunt of the Barbizon painters. Here, they could experiment with rendering landscapes directly, learning to see and translate the nuances of natural light.

In 1864, Gleyre's studio closed due to the master's failing health and eyesight. This event, rather than being a setback, liberated Bazille and his friends to pursue their independent artistic paths more fully. Bazille, with his characteristic generosity, often shared his studio space and resources with his less affluent friends. His studio became a hub of artistic activity and camaraderie.

One of Bazille's earliest significant works from this period is The Pink Dress (La Robe rose), painted around 1864. The painting depicts his cousin, Thérèse des Hours, seated outdoors, her back to the viewer, gazing at the village of Castelnau-le-Lez under the bright southern French sun. This work already shows Bazille's interest in combining figure painting with landscape, and his sensitivity to the effects of sunlight, particularly the way it illuminates the landscape and casts subtle shadows. The composition, with the figure placed somewhat unconventionally, and the fresh, bright palette, hints at the emerging Impressionist aesthetic.

Bazille's financial means allowed him a degree of independence that his friends often lacked. He could afford models, studio space, and materials, and he frequently extended this support to Monet and Renoir, who were often in dire financial straits. This generosity was not merely financial; it was also intellectual and emotional, fostering a collaborative spirit that was crucial to their collective development.

A Generous Patron and a Shared Vision

Frédéric Bazille's affluence, derived from his family's wealth, played a significant, if often understated, role in the early development of what would become Impressionism. Unlike many of his contemporaries who struggled with poverty, Bazille had the means to rent spacious studios and purchase art supplies. More importantly, he possessed a profoundly generous spirit, consistently offering financial and practical support to his friends, particularly Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Throughout the 1860s, Bazille shared several studios with his friends. These shared spaces were not just economical arrangements; they were vibrant centers of artistic exchange and mutual encouragement. One notable studio was on the Rue de Furstenberg, and later, a larger one on the Rue de la Condamine in the Batignolles quarter, an area frequented by avant-garde artists and writers. This latter studio, famously depicted in Bazille's painting Bazille's Studio (L'atelier de Bazille) (1870), became a gathering place for the group. The painting itself is a testament to this camaraderie, featuring portraits of his friends, including Manet, Monet, and Renoir, as well as Bazille himself (painted by Manet).

Bazille's support extended beyond sharing studio space. He often purchased works from his friends to help them financially. A famous instance is his acquisition of Monet's monumental painting Women in the Garden (Femmes au jardin) in 1867. Monet had worked on this large canvas entirely outdoors, facing considerable financial and logistical challenges. When the Salon jury rejected the painting, Bazille stepped in and bought it for 2,500 francs, paying in installments, which provided Monet with a crucial, albeit modest, regular income. This act was a profound gesture of faith in Monet's talent and vision at a time when official recognition was elusive.

He also directly assisted Renoir, who often lived and worked in Bazille's studio. It's said that Bazille would leave out paints and canvases for Renoir to use, understanding his friend's financial difficulties. This environment of shared resources and mutual support was instrumental in allowing these artists to continue their experimental work, free from some of the immediate pressures of poverty. Artists like Camille Pissarro and Edgar Degas were also part of this broader circle, engaging in lively discussions about the future of art.

Bazille's role as a patron and facilitator was thus integral. He was not merely a talented painter in his own right; he was a linchpin who helped to sustain the creative endeavors of his peers during a critical formative period. His generosity fostered a sense of community and shared purpose that was vital for the challenging path they were collectively forging.

Key Works and the Evolution of a Style

Frédéric Bazille's artistic output, though tragically limited to a span of less than a decade, reveals a rapidly evolving talent and a distinctive approach that bridged Realist traditions with emerging Impressionist concerns. His paintings are characterized by a strong sense of structure, a keen observation of light, and a particular interest in depicting figures within natural or contemporary settings.

The Pink Dress (La Robe rose) (c. 1864): As mentioned earlier, this relatively early work is significant. It showcases Bazille's interest in plein-air painting and the integration of figures into a sunlit landscape. The careful rendering of his cousin Thérèse des Hours, combined with the bright, clear light of the South of France, demonstrates his ability to capture both personality and atmosphere. The influence of artists like Gustave Courbet can be seen in the solidity of the figure, while the attention to light prefigures Impressionism.

Bazille's Studio (L'atelier de Bazille) (1870): Also known as Studio in the Rue de la Condamine, this painting is a fascinating document of the artistic life of Bazille and his circle. It depicts a spacious, well-lit studio filled with paintings and artists. Bazille himself, tall and prominent, is shown by the easel (reportedly painted by Édouard Manet, who is also depicted in the scene alongside Monet, Renoir, and possibly the writer Émile Zola and the musician Edmond Maître). The work is a celebration of artistic camaraderie and a statement about modern artistic practice. The figures are rendered with a certain Realist solidity, yet the overall atmosphere is one of contemporary life and artistic endeavor.

Family Gathering (Réunion de Famille) (1867-68): This is arguably Bazille's most ambitious and successful large-scale composition. The painting depicts ten members of his extended family gathered on the terrace of their estate at Méric, near Montpellier, under the shade of a large tree. Each figure is a distinct portrait, rendered with care and psychological insight. The play of sunlight filtering through the leaves, the bright colors of the clothing, and the overall sense of a leisurely summer afternoon are masterfully captured. The work was accepted by the Salon of 1868, a significant achievement. It demonstrates Bazille's skill in complex group portraiture and his ability to infuse a traditional genre with a modern sensibility and a vibrant sense of light and color, reminiscent of the open-air scenes of Manet or even earlier figures like Eugène Boudin, who was a mentor to Monet.

Summer Scene (Bathers) (Scène d'été) (1869): This painting depicts young men in bathing suits relaxing by a riverbank, some swimming, others lounging in the sun or shade. It is a bold exploration of the male nude in a contemporary, natural setting, a subject rarely tackled with such directness at the time. Bazille drew inspiration from classical depictions of bathers but translated the theme into a modern context. The figures are well-modeled, showing his academic training, but the treatment of light on their skin and the surrounding landscape—the shimmering water, the dappled sunlight—is distinctly Impressionistic. The painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1870.

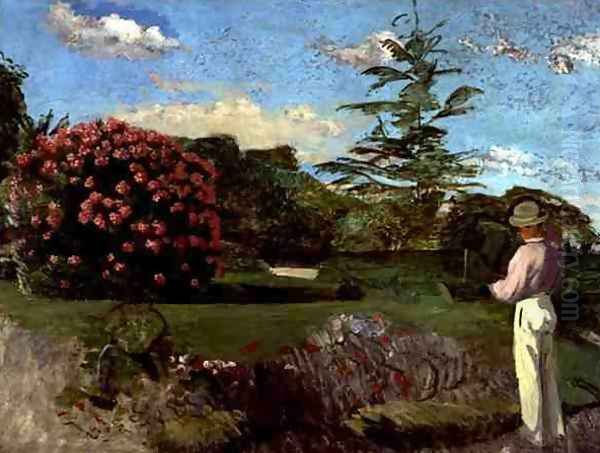

View of the Village (Vue de village) (1868): This work, featuring a young woman (possibly his cousin Pauline Flaugergues) seated in the foreground overlooking the village of Castelnau-le-Lez, is another fine example of Bazille's ability to combine figure painting with landscape. The bright, clear light of the Midi is palpable, and the composition, with its strong diagonal and carefully balanced elements, is sophisticated. The painting exudes a sense of tranquility and harmony, capturing a specific moment in time with clarity and freshness.

Other notable works include The Improvised Field Hospital (L'Ambulance improvisée) (1865), depicting Monet in bed after an accident, tended by Bazille, which showcases his skill in interior scenes and portraiture, and several striking self-portraits, such as Self-Portrait with Palette (1865-66), which convey his serious and dedicated persona. Throughout his oeuvre, Bazille maintained a commitment to clear drawing and solid form, even as he embraced the brighter palette and light-focused concerns of his Impressionist friends. He was less inclined than Monet to dissolve form into light, often seeking a balance between traditional structure and modern optical sensations.

The Salon, Recognition, and Artistic Aspirations

During the 1860s, the official Salon de Paris, organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work and gain recognition. Acceptance by the Salon jury could lead to sales, commissions, and critical acclaim, while rejection often meant obscurity. For Bazille and his avant-garde colleagues, the Salon was a constant source of both aspiration and frustration.

Bazille, like his friends, submitted works to the Salon annually. His experiences were mixed. In 1866, his painting Girl at the Piano (Jeune fille au piano) was rejected, a disappointment shared by many of his peers that year, including Monet and Cézanne, whose works were also turned away. This period saw increasing dissatisfaction with the conservative tastes of the Salon jury, leading to discussions among artists about organizing independent exhibitions—an idea that would eventually culminate in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, an event Bazille would tragically not live to see.

However, Bazille did achieve some Salon successes. His Still Life with Fish was accepted in 1866. More significantly, Family Gathering was accepted for the Salon of 1868. This large, ambitious group portrait, set outdoors, was a notable achievement and garnered some positive attention, demonstrating his ability to work within a relatively traditional format while infusing it with modern sensibilities of light and contemporary life. In 1869, his View of the Village was also accepted.

His final Salon success came in 1870 with Summer Scene (Bathers). This painting, with its depiction of nude male figures in a sun-dappled landscape, was a bold and modern interpretation of a classical theme. Its acceptance indicated a growing, albeit slow, openness to new artistic expressions. However, another work submitted that year, La Toilette (1870), a sensuous depiction of a female nude, was rejected, highlighting the ongoing inconsistencies and conservative biases of the Salon jury. This painting, with its rich colors and intimate subject matter, shows Bazille exploring themes similar to those of Degas or Renoir.

Despite these rejections, Bazille remained committed to his artistic vision. He was actively involved in discussions about alternative exhibition venues. In 1867, he signed a petition, along with Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, and others, requesting the establishment of a new "Salon des Refusés," similar to the one held in 1863 which had famously showcased Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. While this particular petition was unsuccessful, it underscored the growing desire among these artists for independence from the official Salon system.

Bazille's letters from this period reveal his artistic ambitions, his frustrations with the Salon, and his unwavering belief in the new direction art was taking. He was a thoughtful and articulate artist, keenly aware of the challenges and potential of his generation. Had he lived, he would undoubtedly have been a key figure in the organization and execution of the independent Impressionist exhibitions. His Salon entries, both accepted and rejected, chart the course of a painter confidently developing his unique voice, one that skillfully blended careful composition with the vibrant, light-filled aesthetic that would define Impressionism.

The Franco-Prussian War and a Premature End

The summer of 1870 was a period of escalating political tension in Europe. France, under Emperor Napoleon III, declared war on Prussia on July 19, 1870, marking the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War. This conflict would have a profound and devastating impact on France, leading to the fall of the Second Empire and the rise of the Third Republic, and it would tragically cut short the life of Frédéric Bazille.

Despite his comfortable background and burgeoning artistic career, Bazille felt a patriotic duty to serve his country. In August 1870, shortly after the war began, he enlisted in a Zouave regiment, a light infantry unit known for its distinctive North African-inspired uniforms and often deployed in challenging combat roles. His decision was not taken lightly; his letters reveal his anxieties about the war but also his resolve. Many artists were affected by the war: Monet and Pissarro sought refuge in London, while Renoir also served, though in a less perilous capacity. Manet and Degas remained in Paris and served in the National Guard during the subsequent siege of the city.

Bazille's regiment was soon sent to the front lines. The French army, poorly prepared and outmaneuvered by the highly organized Prussian forces, suffered a series of defeats. On November 28, 1870, during the Battle of Beaune-la-Rolande in the Loiret department, Bazille's unit was engaged in fierce fighting. Accounts suggest that his commanding officer was injured, and Bazille, taking command, led an assault on a Prussian position. During this charge, he was struck twice by enemy fire and killed. He was just shy of his twenty-ninth birthday.

The news of his death was a devastating blow to his family and his close circle of artist friends. Monet, Renoir, and Sisley mourned the loss of a dear friend, a generous supporter, and an immensely talented colleague whose artistic journey had been so brutally interrupted. His father, Gaston Bazille, eventually managed to retrieve his son's body from the battlefield, and Frédéric was buried in the Protestant cemetery in Montpellier.

Bazille's death occurred just as he was reaching artistic maturity, with works like Bazille's Studio and Summer Scene demonstrating his growing confidence and unique vision. He did not live to participate in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, an event he had actively discussed and would undoubtedly have championed. His absence was keenly felt, both personally and artistically, by those who were laying the foundations of one of art history's most revolutionary movements. The promise of what he might have achieved, had he lived, remains one of the great "what ifs" of 19th-century art.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Frédéric Bazille's death in 1870, at the age of only 28, meant he never witnessed the official birth and subsequent triumphs of the Impressionist movement he had helped to nurture. He was absent from the seminal 1874 exhibition at Nadar's studio, which gave the group its name, and from the subsequent shows that solidified Impressionism as a major artistic force. Consequently, for many years, his contribution was somewhat overshadowed by his longer-lived contemporaries like Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Sisley.

However, his friends and family ensured his memory and work were not forgotten. His paintings remained largely in the possession of his family for many years, which, while preserving them, also limited their public visibility. Nevertheless, his fellow artists held his talent in high esteem. Renoir, in particular, often spoke of Bazille's importance and the loss his death represented.

Gradual recognition began in the early 20th century. Art historians and critics started to re-evaluate the origins of Impressionism, and Bazille's role as a key precursor and innovator became more apparent. Exhibitions featuring his work began to bring his art to a wider audience. The first major retrospective of his work was held in Paris in 1910. Subsequent exhibitions, such as those at the Wildenstein Gallery in New York (1935), the Musée Fabre in Montpellier (which holds a significant collection of his works, many donated by his family), and later, major international shows like the one organized by the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Musée Fabre, and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (2016-2017), have firmly established his place in art history.

Bazille's paintings are now prized for their unique blend of figurative solidity and luminous, Impressionistic light. Works like Family Gathering, Summer Scene, and Bazille's Studio are considered masterpieces of early Impressionism. Art historians recognize his pioneering efforts in plein-air figure painting, his sophisticated use of color to convey the brilliance of natural light, particularly that of his native Southern France, and his ability to capture the essence of modern life and camaraderie.

His influence can be seen in the way he tackled large-scale compositions featuring figures in outdoor settings, a challenge that many Impressionists, including Monet in his early Déjeuner sur l'herbe (which Bazille knew and admired) and later Women in the Garden (which Bazille purchased), also explored. His generosity and role as a supportive hub for his friends were also crucial, providing stability and encouragement during their formative years. Artists like Gustave Caillebotte, another wealthy Impressionist who acted as a patron to his peers, shared a similar spirit of support for the movement.

Today, Frédéric Bazille is celebrated not just as a promising talent cut short, but as a significant artist in his own right. His relatively small oeuvre is a testament to a clear vision, a profound sensitivity to light and color, and a deep humanity. He stands as a vital link in the chain of artistic development leading to Impressionism, a painter whose light, though extinguished too soon, continues to shine brightly in the annals of art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Light

Frédéric Bazille's story is one of immense talent, profound generosity, and tragic brevity. In less than a decade of dedicated artistic pursuit, he carved out a distinct and influential niche within the nascent Impressionist movement. His ability to meld the structural integrity of figure painting, inherited from his academic training and admiration for Realists like Courbet, with an innovative sensitivity to the transient effects of natural light and color, marked him as a painter of unique vision. He was a bridge between tradition and modernity, comfortable depicting the human form with solidity while simultaneously capturing the fleeting, luminous atmosphere that would become a hallmark of Impressionism.

His friendships with Monet, Renoir, and Sisley were foundational, not only for their personal support but for the collective artistic exploration that took place in shared studios and during plein-air excursions. Bazille's financial stability and open-handedness provided a crucial lifeline for his often-struggling colleagues, fostering an environment where their radical new ideas could germinate. His studio was more than just a workspace; it was a crucible for the ideas that would soon revolutionize painting.

Though he did not live to see the full impact of the movement he helped to shape, or to participate in its defining exhibitions, Bazille's legacy endures. His paintings, from the intimate charm of The Pink Dress to the ambitious scope of Family Gathering and the bold modernism of Summer Scene, reveal an artist of remarkable skill and foresight. His premature death in the Franco-Prussian War was an undeniable loss to the art world, leaving a void where a great talent was still unfolding. Yet, the body of work he left behind, cherished and preserved, continues to speak to us of a world bathed in clear light, of human connection, and of the vibrant artistic spirit of 19th-century Paris. Frédéric Bazille remains an essential figure, a luminous talent whose contributions are integral to understanding the dawn of modern art.