John Rogers Herbert RA (23 January 1810 – 17 March 1890) was a significant English painter whose career spanned a transformative period in British art. Initially recognized for his portraits and romantic genre scenes, Herbert's profound religious convictions, particularly his conversion to Roman Catholicism and later, a shift in his spiritual focus, dramatically reshaped his artistic output. He became a leading figure in the revival of religious and historical painting, most notably contributing monumental frescoes to the New Palace of Westminster. His work, often characterized by its meticulous detail, earnest sentiment, and pioneering use of realistic settings, particularly Middle Eastern landscapes for biblical scenes, left an indelible mark on Victorian art, influencing contemporaries and the succeeding generation of artists, including the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Maldon, Essex, John Rogers Herbert's artistic inclinations were apparent from a young age. He moved to London in 1826 to study at the Royal Academy Schools, where he began to establish himself as a painter. His early career was marked by a practical need to earn a living, leading him to produce book illustrations and portraits. These early works, while competent and often charming, reflected the prevailing tastes of the era, often depicting romantic and literary themes.

During this formative period, Herbert was exposed to a vibrant artistic milieu. London was a hub of artistic activity, with painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable revolutionizing landscape painting, while portraitists such as Sir Thomas Lawrence (who died in 1830, shortly after Herbert's arrival in London) had set a high standard. The Royal Academy, despite its traditionalist leanings, was the epicenter for aspiring artists, and Herbert's training there provided him with a solid technical foundation.

His early subject matter included scenes like The Appointed Hour (1835), which demonstrated a flair for narrative and romantic sentiment. He also painted portraits of notable figures, honing his skills in capturing likeness and character. However, a deeper spiritual searching was beginning to take root, one that would soon steer his art in a profoundly different direction.

The Conversion and a New Artistic Path

A pivotal moment in Herbert's life and career was his conversion to Roman Catholicism in the late 1830s or early 1840s, a decision significantly influenced by his close friend, the architect Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Pugin was a fervent advocate for the Gothic Revival and a devout Catholic, and his passionate beliefs undoubtedly resonated with Herbert. This conversion was a bold step in predominantly Protestant England, even though the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 had improved the civil rights of Catholics.

This spiritual transformation had an immediate and profound impact on Herbert's artistic themes. He began to move away from secular subjects and increasingly focused on religious history, particularly episodes from the Bible and the lives of saints. His work started to align with the broader European trend of religious art revival, partly inspired by the German Nazarene painters like Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, who sought to restore a spiritual sincerity to art by looking back to early Renaissance models.

Works from this period began to reflect his newfound faith. The First Introduction of Christianity into Britain (1842) and Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1843) are indicative of this shift. These paintings were characterized by a more earnest and didactic tone, aiming to convey spiritual truths and historical religious narratives with clarity and emotional depth. His style began to incorporate a greater emphasis on linear precision and a more subdued palette, reflecting a desire for gravitas and sincerity.

A Defining Friendship: Herbert and A.W.N. Pugin

The friendship between John Rogers Herbert and Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was one of the most significant personal and professional relationships in Herbert's life. They met as young men, and their bond deepened through shared artistic and religious convictions. Pugin, a leading figure in the Gothic Revival movement and co-architect of the New Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) alongside Sir Charles Barry, was a passionate advocate for an art and architecture rooted in medieval Christian principles.

Pugin's influence on Herbert was manifold. He not only played a role in Herbert's conversion to Catholicism but also shaped his understanding of religious art's purpose and aesthetics. Pugin believed that art should serve a moral and spiritual function, and that the Gothic style was the purest expression of Christian art. While Herbert did not fully adopt a medievalist style in the same way Pugin did in architecture, he absorbed the emphasis on sincerity, historical accuracy (as then understood), and the didactic potential of art.

Their collaboration extended to practical matters. Pugin commissioned Herbert for various projects, and they often discussed artistic and theological ideas. Herbert's portrait of Pugin, painted in 1845 and now in the UK Parliamentary Art Collection, is a testament to their close relationship, capturing the architect's intense and visionary character. This portrait is considered one of Herbert's finest. The intellectual and spiritual exchange between these two men was a vital force in the religious art revival in Victorian England.

The Westminster Frescoes: A Monumental Commission

Herbert's growing reputation as a painter of serious historical and religious subjects led to his involvement in one of the most ambitious artistic projects of the 19th century: the decoration of the New Palace of Westminster. Following the fire of 1834 that destroyed the old Houses of Parliament, a massive rebuilding project was initiated, designed by Charles Barry with Pugin responsible for the intricate Gothic detailing. A Royal Commission was established to oversee the decoration of the new building with frescoes and sculptures that would celebrate British history and values.

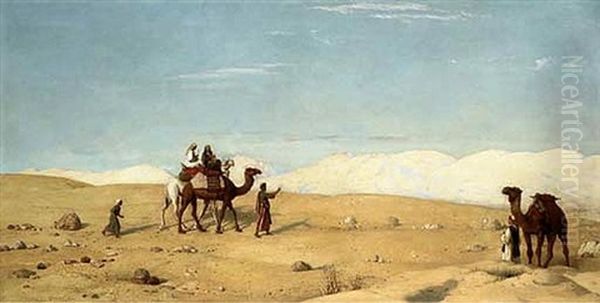

Herbert was selected to paint several large-scale frescoes in the Poets' Hall and later, more significantly, in the Peers' Robing Room. His most famous works here include The Judgement of Daniel and Moses Descending from the Mount with the Tables of the Law (completed 1864). For Moses, Herbert undertook extensive research, including travels to the Middle East, to ensure the accuracy of the landscape and details. This commitment to realism, particularly in depicting biblical scenes in their authentic geographical settings, was a pioneering approach at the time.

The fresco technique itself was relatively new and challenging for British artists, who were more accustomed to oil painting. Artists like William Dyce and Daniel Maclise, who were also involved in the Westminster project, experimented with various fresco methods, including the German "Keim's process" or stereochromy (waterglass painting), which Herbert also adopted. These monumental works were intended to be didactic and morally uplifting, reflecting the high Victorian ideals of art's public role. Herbert's frescoes were praised for their grandeur, solemnity, and the earnestness of their religious conviction, though the challenging medium and the vast scale presented ongoing technical difficulties for many artists involved.

Artistic Style, Thematic Concerns, and "Pre-Rosetta-ism"

John Rogers Herbert's artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career, but it consistently demonstrated a commitment to meticulous detail, strong draughtsmanship, and a desire to convey profound emotional and spiritual content. After his conversion, his primary thematic concerns revolved around biblical narratives, scenes from Christian history, and subjects imbued with moral or religious significance.

A notable aspect of Herbert's later style was his pioneering effort to depict biblical scenes with ethnographic and geographical accuracy. His travels to Egypt and Palestine in the late 1850s and early 1860s were undertaken to study the landscapes, people, and customs of the Holy Land. This research was then incorporated into his paintings, lending them a novel sense of realism. Works like Our Saviour Subject to His Parents at Nazareth (1847) and later paintings based on his travels, such as The Valley of Moses, in the Desert of Sinai (1868), showcase this approach. This desire for historical and topographical accuracy in religious subjects predated and influenced similar tendencies in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Indeed, Herbert is sometimes considered a "Pre-Rosetta-ist" or, more accurately, a significant precursor to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), which was officially formed in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais. Herbert's emphasis on truth to nature, detailed rendering, serious subject matter, and a rejection of the more formulaic academic conventions resonated with the ideals of the young Pre-Raphaelites. While not a member of the PRB, his work was admired by them, and he shared their interest in reviving an earlier, more sincere mode of painting. His commitment to depicting religious scenes with fresh observation rather than relying on established iconographic traditions was particularly influential.

His representative works, beyond the Westminster frescoes and the Pugin portrait, include The Youth of Our Lord (also known as Our Saviour Subject to His Parents at Nazareth), which was praised for its tender domesticity and realistic detail. Another significant piece, Laborare est Orare (To Labor is to Pray), depicts monks engaged in agricultural work, embodying the dignity of labor and its connection to spiritual life, a theme that would also resonate with thinkers like John Ruskin and artists like Ford Madox Brown.

Collaborations and Influence on Contemporaries

Beyond his close association with Pugin, Herbert was an active member of the London art world. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1841 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1846. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy exhibitions, where his works were seen by a wide public and fellow artists.

His role as "figure master" at the newly established Government School of Design at Somerset House from 1841, a position possibly secured with the help of his friend William Dyce (who was the school's director), placed him in a position to influence younger artists. Dyce himself was a versatile artist involved in religious painting and the Westminster decorations, and their shared interests likely fostered a productive professional relationship. Herbert and Dyce had previously collaborated on illustrations for Nursery Rhymes, Tales and Jingles.

Herbert's influence on the Pre-Raphaelites is perhaps his most noted impact on contemporary painters. While artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti developed their own distinct styles, the PRB's initial aims – to paint with directness, sincerity, and attention to natural detail, often tackling serious literary or religious themes – found an echo and a precedent in Herbert's work of the 1840s. William Holman Hunt, in particular, would later take the commitment to Middle Eastern accuracy in biblical painting to an even greater extent. The seriousness with which Herbert approached religious art helped create a climate where such themes could be explored with renewed vigor by younger artists. Other artists of the period, such as Charles West Cope and Edward Armitage, were also engaged in historical and religious painting, contributing to a broader revival of these genres.

Personal Life: Anecdotes and Character

John Rogers Herbert's personal life was deeply intertwined with his religious faith and his art. His conversion to Catholicism was a defining event, shaping not only his artistic output but also his social circle and personal conduct. He was known for his devoutness and the seriousness with which he approached his vocation as an artist.

An interesting anecdote relates to his later spiritual shift. While initially a fervent Roman Catholic, in his later years, sources suggest Herbert's religious views evolved, moving towards a more general Christian belief, though he always retained a profound spirituality. This internal journey may have been reflected in the changing nuances of his religious art.

Herbert's family life was also significant. He married, and some of his children also became artists, notably his son Cyril Wiseman Herbert. The family home was a place where art and faith were central.

However, his career was not without its setbacks. One notable incident involved a major commission for the Royal Academy, where one of his works was accidentally destroyed. This event reportedly had a negative impact on the market demand for his paintings for a time, a significant blow for an artist reliant on sales and commissions.

In his later years, Herbert suffered from declining health. He experienced a stroke and increasing paralysis, which severely hampered his ability to paint. He officially retired from the Royal Academy in 1886. Despite these physical challenges, his commitment to his art and faith remained. He had built a house, The Chimes, in Kilburn, London, designed in a Gothic style, reflecting his and Pugin's aesthetic preferences. He later moved to St John's Wood.

Herbert was also involved in charitable activities. He was a founder of the St. Vincent's Home for Destitute Boys and supported the "Pence-Peter's Association" (likely a reference to Peter's Pence, a collection for the Pope), which aimed to help educate impoverished boys. These activities underscore the practical application of his Christian principles.

Controversies and Critical Reception in Art History

John Rogers Herbert's career, while distinguished, was not without controversy, and critical reception of his work varied over time.

1. Religious Conversion and Style: His conversion to Catholicism and the subsequent shift in his subject matter were significant. While this brought him commissions and aligned him with the religious art revival, it also placed him somewhat outside the mainstream Protestant establishment in Britain. Later, as his specific adherence to Roman Catholicism perhaps softened, the intense focus on religious themes continued, but some critics felt his later works, particularly those emphasizing Middle Eastern realism, sometimes lacked the spiritual depth or traditional iconographic resonance expected in religious art. They were seen by some as overly descriptive or ethnographic.

2. The Westminster Frescoes: While a prestigious commission, the Westminster frescoes project was fraught with technical difficulties for all artists involved. The damp London climate was not ideal for true fresco, and many of the works deteriorated over time. Herbert's use of the stereochromy (waterglass) technique for his Moses was an attempt to find a more durable solution, but even these faced challenges. Furthermore, the sheer scale and public nature of these works invited intense scrutiny and occasional criticism regarding composition, style, or interpretation.

3. Artistic Techniques and Market: The anecdote about a destroyed work affecting his market value highlights the precariousness of an artist's career. There were also discussions about the pricing of his works. Some of his experimental techniques, or perhaps the perceived intensity of his religious subjects, might have made his work less universally popular compared to painters of more secular or sentimental Victorian scenes like William Powell Frith or animal painters like Sir Edwin Landseer.

4. Relationship with Pugin and Gothic Revival: While his friendship with Pugin was formative, Pugin's own uncompromising and sometimes dogmatic views on Gothic art could be controversial. Herbert, while influenced, maintained his own artistic identity. There might have been underlying tensions or debates about the precise direction religious art should take – whether a strict adherence to medieval models (Pugin's preference) or a more contemporary interpretation incorporating realism (Herbert's path).

5. Acceptance of Large-Scale Works: Some of Herbert's ambitious, large-scale paintings faced challenges in finding permanent homes or being exhibited. For instance, there's a report that his large Moses Delivering the Law was offered to the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia but was declined due to its size, indicating the practical difficulties of placing such monumental works.

Despite these controversies, Herbert was a respected figure. He was a Royal Academician for many decades and played a key role in major national artistic projects. His commitment to elevating the status of religious art in Britain was undeniable. Later art historical assessments have recognized his pioneering role in introducing greater realism to biblical scenes and his influence on the Pre-Raphaelites. However, like many Victorian artists who fell out of fashion in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism, his work has perhaps not always received the sustained attention it merits, though there has been a renewed scholarly interest in Victorian art in recent decades. Artists like George Frederic Watts or Frederic Leighton, who also tackled grand themes, perhaps overshadowed him in later public perception.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

The later years of John Rogers Herbert's life were marked by declining health. After suffering a stroke, he became increasingly incapacitated, leading to his retirement from active participation in the Royal Academy in 1886. He passed away on 17 March 1890 at his home, The Chimes, in Kilburn, London.

Herbert's legacy is multifaceted. He was a key figure in the 19th-century revival of religious painting in Britain, bringing a new seriousness and, notably, a commitment to historical and geographical realism to biblical subjects. His monumental frescoes in the Palace of Westminster stand as a testament to his ambition and skill in large-scale narrative art, contributing significantly to one of the grandest decorative schemes of the Victorian era.

His influence on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly in their early formation and their shared desire for "truth to nature" and serious subject matter, is an important aspect of his impact. Artists like William Holman Hunt directly followed his example in traveling to the Holy Land to paint biblical scenes with authentic settings.

While the taste for overtly religious and didactic Victorian art waned in the 20th century, there has been a growing appreciation for the complexity and achievements of artists like Herbert. His dedication to his faith and his art, his pioneering spirit in seeking authenticity, and his significant contributions to public art ensure his place in the history of British art. His works can be found in major collections, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the UK Parliamentary Art Collection. He remains a compelling example of a Victorian artist grappling with the intersections of faith, history, and artistic expression in a rapidly changing world, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both personal conviction and the broader cultural currents of his time. His portrait of Pugin remains an iconic image of one of the era's most dynamic figures, and his own religious paintings helped redefine the genre for a new generation, including artists like Edward Burne-Jones who would continue to explore spiritual and mythological themes with great intensity.