Introduction: An English Eye on the East

John Frederick Lewis (1805-1876) stands as one of the most accomplished and distinctive figures in nineteenth-century British art. While his contemporaries explored diverse themes from historical narratives to modern life, Lewis carved a unique niche for himself, becoming a preeminent master of Orientalist painting. His work is celebrated for its extraordinary attention to detail, brilliant rendering of light and colour, and evocative depictions of life in Spain, Italy, and, most significantly, the Middle East, particularly Egypt. Lewis possessed a rare ability to combine meticulous realism with a palpable sense of atmosphere, transporting viewers into the sunlit courtyards, bustling markets, and serene interiors he observed during his extensive travels. His dedication to capturing the intricacies of different cultures, especially those of the Ottoman world, resulted in a body of work that remains captivating for its technical brilliance and cultural insight.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in London in 1805, John Frederick Lewis was immersed in the world of art from his earliest years. His father, Frederick Christian Lewis the Elder (1779–1856), was a respected engraver and landscape painter, providing the young Lewis with his initial artistic training and a stimulating creative environment. His uncle, Charles Lewis, was a renowned bookbinder, and his younger brothers, Charles George Lewis and Frederick Christian Lewis the Younger, also pursued careers as artists, primarily engravers. This familial connection to the arts undoubtedly shaped his path.

Lewis initially showed a remarkable talent for animal painting, a genre highly popular in England at the time. His early studies of wildlife demonstrated a keen eye for observation and anatomical accuracy. This skill brought him to the attention of the eminent portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence, who commissioned Lewis to paint animals within his own portraits. Furthermore, Lewis formed a close childhood friendship with another future giant of British art, Sir Edwin Landseer, who would become the era's foremost animal painter. Their shared interests likely spurred Lewis's early development in this field.

He began exhibiting his work at major London venues like the British Institution and the Royal Academy of Arts while still a teenager. His early paintings often featured animals in landscape settings, showcasing his burgeoning technical skills. However, his artistic interests soon began to broaden beyond the confines of animal portraiture, hinting at the more complex and exotic subjects that would later define his career. He also mastered the techniques of watercolour, a medium in which he would achieve extraordinary proficiency. By 1827, he was accomplished enough to establish his own studio and, in 1829, he was elected an Associate of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (often known as the Old Watercolour Society or OWS), becoming a full member in 1830.

Broadening Horizons: Travels in Spain and Italy

The late 1820s and 1830s marked a period of significant travel and artistic evolution for Lewis. Seeking fresh inspiration and subject matter beyond British shores, he embarked on extensive tours of continental Europe. His travels took him through Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, but it was his extended stay in Spain between 1832 and 1834 that proved particularly formative. Spain, with its rich history, distinct culture, and dramatic landscapes, offered a wealth of new visual stimuli.

During his time in Spain, Lewis produced numerous sketches and watercolours, capturing the vibrant street life, traditional costumes, and stunning Moorish architecture, particularly in cities like Granada and Seville. His fascination with the legacy of Islamic culture in Andalusia, especially the intricate beauty of the Alhambra palace in Granada, foreshadowed his later deep engagement with the Middle East. Works like The Alhambra (numerous studies) and depictions of Spanish festivals and bullfights showcased his growing mastery of complex compositions and his ability to render textures and light with increasing sophistication.

His Spanish works, often executed in watercolour heightened with bodycolour (opaque watercolour or gouache), were noted for their brilliance and detail. He shared this interest in Spain with other British artists, including David Wilkie and David Roberts, whose paths sometimes crossed or paralleled his own travels. Lewis's Spanish subjects proved popular back in England, enhancing his reputation as a skilled and adventurous artist. His time in Italy, particularly Rome and Venice, further refined his understanding of light and composition, though it was the allure of Spain that seemed to resonate more deeply with his developing artistic identity.

The Decade in Egypt: Immersion and Mastery

The pivotal chapter in John Frederick Lewis's artistic life began in 1841 when he arrived in Cairo, Egypt. Initially intended as part of a longer journey that had already taken him through Greece and Constantinople (Istanbul), his stay in Cairo extended for a remarkable ten years, until 1851. This decade proved transformative, providing the defining subject matter for the remainder of his career and cementing his reputation as a leading Orientalist painter.

Unlike many European artists who made brief tours of the East, Lewis fully immersed himself in Cairene life. He adopted local dress, learned Arabic, and lived in a grand, traditional Ottoman-era house in the Esbekiya (Azbakiyyah) district. This deep immersion allowed him an intimate perspective on the culture, customs, and daily rhythms of the city, far removed from the fleeting impressions of a casual tourist. His lifestyle became legendary; the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray visited him in Cairo in 1844 and famously described Lewis living "like a languid Lotus-eater," surrounded by exotic comforts, though this perhaps downplayed the intense artistic activity Lewis undertook.

During this decade, Lewis produced a vast number of highly detailed sketches and studies of Cairo's architecture, interiors, markets, mosques, and people. He meticulously documented the intricate details of mashrabiya (wooden lattice screens), tilework, carpets, metalwork, and traditional clothing. These studies formed the raw material for the highly finished watercolours and, later, oil paintings he would create upon his return to England. His focus shifted decisively towards depicting scenes of Egyptian life, both public and private, often characterized by a sense of tranquil observation.

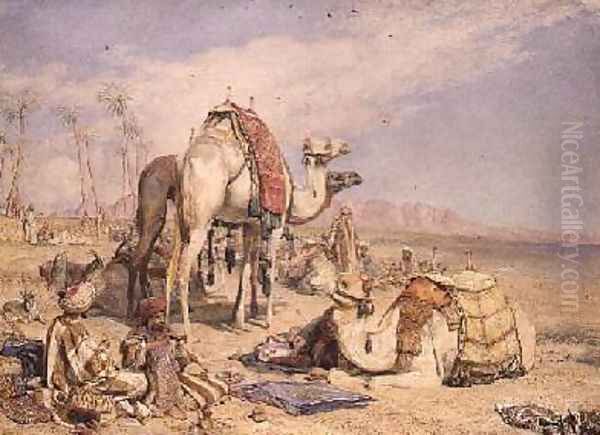

Key works stemming from this period, though often completed later, include A Frank Encampment in the Desert of Mount Sinai, 1842 (completed 1856, Yale Center for British Art), a panoramic watercolour depicting the party of a Scottish nobleman, Lord Castlereagh, whom Lewis may have encountered. Another seminal work is The Harem (c. 1850, versions at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and Victoria and Albert Museum, London), exhibited upon his return. This complex interior scene, likely using his own house and possibly his future wife as models, offered a glimpse into the secluded world of the Ottoman elite, rendered with astonishing detail and sensitivity to light.

Return to England: Acclaim and Evolution

When John Frederick Lewis returned to England in 1851, he brought with him an extraordinary portfolio of sketches and studies from his decade in Cairo. The exhibition of his finished Egyptian watercolours at the Old Watercolour Society caused a sensation. Works like The Harem were lauded for their unprecedented detail, luminous colour, and seemingly authentic portrayal of Eastern life. The critic John Ruskin, a powerful voice in Victorian art, initially showered Lewis's work with praise, comparing its intricate detail to that of the Pre-Raphaelites and extolling its truthfulness.

Lewis's success propelled him to the forefront of the British art scene. In 1855, he was elected President of the Old Watercolour Society, a testament to his standing among his peers. However, Lewis grew frustrated with the OWS rules, which restricted members from exhibiting oil paintings elsewhere, particularly at the more prestigious Royal Academy. Watercolour paintings generally commanded lower prices than oils, and Lewis, seeking greater recognition and financial reward, decided to shift his focus.

In 1858, he resigned from the OWS presidency and membership to concentrate on oil painting, adapting his meticulous watercolour technique to the new medium. This move proved successful. He began exhibiting large, highly finished oil paintings of Orientalist subjects at the Royal Academy, where they were met with critical acclaim and fetched high prices. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1859 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1865. His oil paintings retained the hallmark characteristics of his watercolours: intricate detail, brilliant light effects, and carefully composed scenes of Middle Eastern life.

Notable works from this later period include An Arab Scribe, Cairo (1852), A Halt in the Desert (1855), Street Scene, Cairo (The Carpet Seller) (c. 1856), The Midday Meal, Cairo (1875), and the poignant And the Prayer of Faith Shall Save the Sick (1872). His final major work, exhibited posthumously, was On the Banks of the Nile, Upper Egypt (1876). Occasionally, he revisited earlier themes, as seen in Roman Pilgrims (1854), demonstrating the enduring influence of his Italian travels.

Artistic Style and Technique: The Pursuit of Detail and Light

John Frederick Lewis's artistic style is defined by several key characteristics that set him apart from many of his contemporaries and contributed significantly to his enduring reputation.

Meticulous Detail and Realism: Lewis possessed an almost obsessive commitment to rendering detail with extraordinary precision. His paintings are filled with intricate depictions of architectural elements like mashrabiya screens and Iznik tiles, the complex patterns of textiles and carpets, the gleam of metalwork, and the textures of various surfaces. This microscopic attention to detail invited close inspection and lent his scenes a powerful sense of authenticity. His level of finish was often compared to the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, such as William Holman Hunt or John Everett Millais, although Lewis developed his detailed style independently through direct observation.

Mastery of Light and Colour: Central to Lewis's art is his exceptional handling of light. He masterfully captured the intense, clear sunlight of the Mediterranean and the Middle East, contrasting brilliant highlights with deep, cool shadows. His interior scenes are often illuminated by complex patterns of light filtering through screens or falling across courtyards, creating a palpable sense of atmosphere and place. His palette was rich and luminous, employing vibrant colours to convey the richness of fabrics and decorative elements, while maintaining overall tonal harmony.

Watercolour and Oil Proficiency: Lewis was a supreme master of watercolour, often using a combination of transparent washes and opaque bodycolour (gouache) on paper. This technique allowed him to achieve both luminosity and solidity, creating jewel-like surfaces packed with detail. When he transitioned back to oil painting later in his career, he adapted his meticulous methods, applying paint in fine layers to achieve a similar level of intricate finish and brilliance, demonstrating remarkable technical versatility across both mediums.

Orientalist Themes and Representation: Lewis's primary subject matter was the life and culture of the places he visited, particularly Egypt. His Orientalism, however, often differed from that of some French contemporaries like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres or Eugène Delacroix, whose Eastern scenes could be more overtly romanticized or sexualized. Lewis's depictions, while sometimes idealized, generally stemmed from careful observation. Notably, his portrayals of women, especially in harem scenes (often featuring his wife, Marian Harper Lewis, as a model), tend to emphasize domesticity, composure, and elaborate costume rather than eroticism, offering a more reserved and arguably respectful perspective compared to some other Orientalist visions.

Idealization within Observation: While lauded for realism, Lewis's works were not simply photographic transcriptions. He carefully composed his scenes, sometimes combining elements observed at different times or places. He often depicted an idealized vision of traditional Egyptian life, focusing on serene, well-ordered interiors and seemingly timeless customs, largely omitting the increasing Western influence or the harsher realities of poverty that existed in nineteenth-century Cairo. His art presents a carefully curated, aesthetically refined vision of the East.

Lewis and His Contemporaries: Connections and Context

Throughout his long career, John Frederick Lewis interacted with, influenced, or was compared to numerous other artists and cultural figures, placing him firmly within the vibrant artistic landscape of the Victorian era.

His early friendship with Sir Edwin Landseer connected him to the heart of the British art establishment. His travels brought him into the orbit of fellow artists exploring similar territories. In Spain, the work and presence of Sir David Wilkie, a pioneer of genre painting who also travelled extensively, provided context. Lewis's relationship with David Roberts, another prominent British Orientalist known for his topographical views and lithographs, was one of shared interest rather than close personal contact, though their works were often discussed together as leading examples of British engagement with the East.

During his time in Cairo, Lewis encountered other European travellers and artists, though perhaps none as significant as William James Müller, who visited Cairo shortly before Lewis settled there. The famous visit by William Makepeace Thackeray resulted in a vivid, albeit somewhat romanticized, account of Lewis's Cairene existence in Thackeray's travelogue, Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo (1846).

Back in London, Lewis's work inevitably drew comparisons with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), particularly William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Although Lewis was older and stylistically independent, his intense detail and bright colour palette resonated with PRB aesthetics, leading the influential critic John Ruskin to champion his work alongside theirs for its perceived "truth to nature." However, Ruskin later cooled towards Lewis, perhaps finding his later oils less spiritually profound than the work of the PRB.

Lewis's decision to switch from watercolour to oil painting brought him more directly into competition and comparison with leading Royal Academicians. Figures like Frederic Leighton, another Victorian giant who explored classical and occasionally Orientalist themes with a polished academic finish, represent the high standards of the RA during Lewis's later career. While Lewis maintained a somewhat aloof position from the internal politics of the RA, his election as an Academician confirmed his status.

Internationally, Lewis's detailed realism found parallels and likely exerted influence on French Orientalist painters. Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his highly finished, almost photographic depictions of Middle Eastern scenes, seems particularly indebted to the standard of meticulous detail set by Lewis. Other French artists like Adrien Dauzats, who also travelled and depicted the East, worked within a similar sphere of interest. Decorative artists like Henri Lévy may also have drawn inspiration from Lewis's rich colour and exotic subject matter.

Later Life, Legacy, and Influence

John Frederick Lewis married Marian Harper Lewis in 1847, likely in Alexandria. She appears frequently as a model in his Cairene and later paintings, embodying the serene female figures that populate his domestic interiors. After their return to England, they eventually settled in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, where Lewis continued to paint prolifically until his final years.

Towards the end of his life, Lewis suffered from declining health. Anecdotes suggest he experienced paralysis, possibly from a stroke, which eventually confined him to a wheelchair. Despite these challenges, he continued working, producing significant paintings until shortly before his death. He passed away at his home in Walton-on-Thames on August 15, 1876, and was buried in the graveyard of Frimley church, Surrey.

Following his death, Lewis's reputation experienced a period of relative decline, as artistic tastes shifted away from Victorian detailed realism towards Impressionism and modernism. However, the mid-to-late twentieth century saw a significant reassessment and revival of interest in his work. Scholars and collectors rediscovered the extraordinary technical skill, unique observational qualities, and captivating beauty of his paintings. Today, his works are highly sought after and hold prominent places in major museum collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Gallery London, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Lewis's influence extended beyond his immediate contemporaries. His meticulous technique and commitment to observed detail set a high standard for realism in Orientalist painting, particularly influencing Jean-Léon Gérôme in France. His work provided British audiences with vivid, albeit sometimes idealized, images of the Middle East, shaping Victorian perceptions of the region. While Orientalism as a genre has faced critical scrutiny in post-colonial theory (notably by Edward Said) for potentially reinforcing stereotypes, Lewis's work is often seen as more nuanced and based on deeper personal experience than that of many other European artists who depicted the East. His legacy lies in his unique fusion of intricate craftsmanship, sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and his dedicated, immersive portrayal of the cultures he encountered.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

John Frederick Lewis remains a singular figure in the history of British art. He was a bridge between the intimate medium of watercolour, in which he was an undisputed master, and the grander ambitions of oil painting. His career path, marked by extensive travel and a decade of deep immersion in Egyptian culture, set him apart from artists who remained closer to home. His dedication to capturing the intricate details of the worlds he observed, combined with his extraordinary ability to render the effects of light and colour, resulted in paintings that are both visually stunning and culturally evocative.

While firmly rooted in the Victorian era, Lewis's work transcends mere historical documentation or exotic fantasy. It offers a unique, meticulously crafted vision of Spain and the Middle East, filtered through the lens of a highly skilled and observant English artist. His paintings continue to fascinate viewers with their technical brilliance, atmospheric depth, and the window they provide into the opulent interiors and sun-drenched landscapes that captured his imagination for a lifetime. John Frederick Lewis's contribution to Orientalist painting, and to British art as a whole, secures his place as a master of enduring significance.