Gabriel-François Doyen (1726–1806) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the rich tapestry of 18th-century French art. His career unfolded during a period of profound stylistic transition, witnessing the full flowering of the Rococo, the sober reaction against it, and the eventual triumph of Neoclassicism. Doyen, a master of historical and religious painting, navigated these shifting currents with considerable skill, producing works of dramatic power and emotional intensity. His journey took him from the studios of Paris to the hallowed halls of Rome, and ultimately to the imperial court of Russia, leaving a legacy that reflects both the grandeur of the late Baroque tradition and the burgeoning sensibilities of a new era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris in 1726, Gabriel-François Doyen exhibited an early passion for art. This nascent talent led him, at the tender age of twelve, to the prestigious studio of Charles-André van Loo, more commonly known as Carle Van Loo. Carle Van Loo was himself a towering figure in French art, a versatile painter celebrated for his historical scenes, portraits, and mythological subjects. He was a key proponent of the "grand manner," a style that emphasized noble themes, idealized figures, and harmonious compositions, albeit often infused with a Rococo lightness and elegance.

Under Van Loo's tutelage, Doyen would have received a rigorous academic training. This involved meticulous drawing from casts of antique sculptures, life drawing, and the study of compositional principles as laid down by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Van Loo's own style, which blended Italian Baroque influences with French Rococo grace, undoubtedly shaped Doyen's early artistic vision. The emphasis on large-scale historical and religious narratives, a hallmark of Van Loo's oeuvre, became a central focus of Doyen's own ambitions.

Doyen's prodigious talent quickly became apparent. In 1746, at the age of twenty, he achieved a significant milestone by winning the coveted Grand Prix de Rome. This prestigious award, granted by the Royal Academy, provided promising young artists with a scholarship to study in Rome for several years. It was an unparalleled opportunity to immerse oneself in the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods, considered essential for any artist aspiring to the "grand manner."

The Roman Sojourn: Immersion in the Masters

The Prix de Rome was a gateway to a transformative experience for Doyen, as it was for many artists of his generation, including contemporaries like Jean-Honoré Fragonard, who would also spend time in Italy. Arriving in Rome, Doyen embarked on an intensive period of study. He diligently copied ancient sculptures and the works of the great Italian masters, absorbing their techniques and artistic philosophies.

He was particularly drawn to the dramatic power and compositional dynamism of High Baroque painters. The works of Annibale Carracci, with his blend of classical idealism and naturalistic observation, left a profound mark. Doyen studied Carracci's frescoes in the Palazzo Farnese, marveling at their heroic figures and complex narratives. Pietro da Cortona, another luminary of the Roman Baroque, known for his exuberant and illusionistic ceiling paintings, also captured Doyen's imagination. The sheer scale and theatricality of Cortona's work, such as the ceiling of the Palazzo Barberini, offered a model for ambitious, large-scale compositions.

Furthermore, Doyen delved into the legacy of earlier masters. Giulio Romano, a principal pupil of Raphael, whose Mannerist style was characterized by muscular figures and dramatic intensity, provided another source of inspiration. And, of course, the towering genius of Michelangelo, particularly his work in the Sistine Chapel, offered an enduring example of anatomical power and sublime expression. The influence of Caravaggio, with his dramatic use of chiaroscuro and unflinching realism, and Guido Reni, with his elegant classicism and refined sentiment, also filtered into Doyen's developing artistic vocabulary.

Beyond Rome, Doyen's thirst for knowledge led him to other artistic centers in Italy. He traveled to Naples, where he would have encountered the vibrant Neapolitan Baroque tradition. Venice, with its rich colorito and the legacy of masters like Titian and Veronese, offered further lessons in painterly technique and opulent display. Bologna, home to the Carracci academy and a strong tradition of classical painting, also formed part of his Italian itinerary. This comprehensive immersion in Italian art, spanning several years, was crucial in shaping Doyen's mature style. He returned to Paris in 1755, his artistic vision broadened and his technical skills significantly honed.

Return to Paris and Academic Ascent

Upon his return to Paris in 1755, Doyen initially found that recognition was not immediate. The Parisian art world was highly competitive, dominated by established figures and subject to the shifting tastes of patrons and critics. However, Doyen was determined to make his mark. He set about creating a major work that would showcase his talents and announce his arrival on the Parisian scene.

This ambition culminated in his 1758 painting, The Death of Virginia. The subject, drawn from Roman history as recounted by Livy, tells the tragic story of Virginia, a plebeian girl whose father kills her to save her from the lecherous advances of the decemvir Appius Claudius. This theme, with its overtones of civic virtue, sacrifice, and resistance to tyranny, resonated with the growing interest in classical subjects that would later coalesce into Neoclassicism. Doyen's treatment of the scene was likely imbued with the dramatic intensity and pathos he had absorbed from his Italian studies.

The Death of Virginia proved to be a critical success. It was exhibited at the Salon, the official art exhibition of the Royal Academy, and garnered considerable attention. More importantly, it served as Doyen's reception piece for the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. His election to this prestigious institution was a significant step, officially recognizing him as a master painter and allowing him to receive royal commissions and participate fully in the artistic life of the capital. He was now part of an esteemed body that included artists like François Boucher, the leading Rococo painter, and the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle.

Masterpieces and Major Commissions

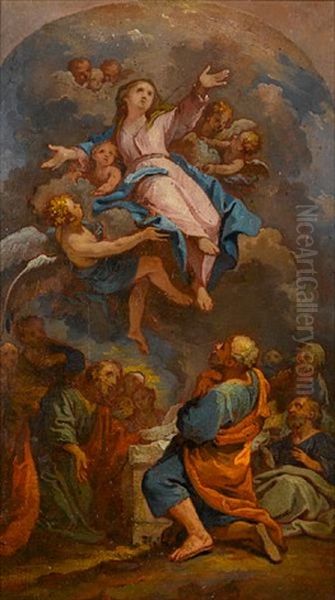

Following his admission to the Academy, Doyen's career gained momentum. He received a series of important commissions for large-scale religious and historical paintings, which became his specialty. These works allowed him to deploy the full range of his skills, combining dramatic composition, expressive figures, and rich color.

One of his most celebrated achievements is Le Miracle des Ardents (The Miracle of the Burning Sickness, or St. Genevieve Interceding for the Plague-Stricken), painted in 1767 for the church of Saint-Roch in Paris, though originally intended for a chapel dedicated to Saint Geneviève in the church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois before being re-routed to Saint-Roch due to complex commissioning histories, and eventually finding its way to Saint-Geneviève's chapel in Saint-Roch. This monumental canvas depicts Saint Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris, miraculously curing victims of ergotism, a disease that caused a burning sensation in the limbs. Doyen's composition is a tour-de-force of Baroque drama, filled with writhing figures, desperate expressions, and a palpable sense of divine intervention. The influence of Peter Paul Rubens, whose work Doyen had admired, possibly during a trip that included Brussels, is evident in the painting's dynamic energy, rich coloration, and robust figures. This work was widely praised and solidified Doyen's reputation as a leading religious painter. Diderot, the influential art critic, though often critical, acknowledged the power of this work.

Also in 1767, Doyen completed The Triumph of Thérèse for the Church of Saint-Roch. This work, likely depicting the ecstatic vision of Saint Teresa of Ávila, would have showcased his ability to convey intense spiritual emotion through dramatic gesture and composition, a hallmark of Baroque religious art.

Another significant commission was The Death of Saint Louis, completed in 1769 for the chapel of the École Militaire (Military School) in Paris. This painting depicted the pious French king, Louis IX, dying during the Eighth Crusade in Tunis. The subject was both religious and patriotic, celebrating a revered national hero and saint. Doyen's portrayal likely emphasized the king's piety and noble sacrifice, themes that resonated with the moralizing tendencies of the era. These large-scale works demonstrated Doyen's mastery of complex multi-figure compositions and his ability to convey grand historical and religious narratives with emotional force. His style, while rooted in the Baroque, often displayed a clarity and a focus on dramatic essentials that distinguished it from the more decorative excesses of the Rococo.

The "Swing" Anecdote and Artistic Integrity

An interesting anecdote illuminates Doyen's artistic principles and his position within the diverse art scene of his time. He was reportedly approached by a courtier, Baron de Saint-Julien, with a rather risqué commission. The Baron wished for a painting depicting his mistress on a swing, being pushed by a bishop, while he himself would be positioned to look up her skirts. The subject was typical of the lighthearted, amorous themes favored by some Rococo patrons.

Doyen, however, found the subject matter too frivolous and perhaps morally objectionable for his artistic temperament, which leaned towards more serious and elevated themes. He declined the commission, famously suggesting that it might be more suited to the talents of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Fragonard, a fellow student from the Carle Van Loo studio and a Prix de Rome winner, was renowned for his mastery of Rococo charm and sensuality. Fragonard accepted the commission and went on to create his iconic masterpiece, The Swing (Les Hasards heureux de l'escarpolette), around 1767. While Fragonard modified the details (the pusher became a layman, not a bishop, in most interpretations), the essential playful eroticism remained.

This incident highlights the different artistic paths taken by Doyen and Fragonard, despite their shared early training. Doyen's refusal underscores his commitment to the "grand manner" and historical painting, distinguishing him from artists who more readily embraced the lighter, more intimate themes of the Rococo. It speaks to a certain seriousness in his artistic vision, a preference for subjects of historical or moral weight.

Teaching, Royal Patronage, and Later Career in Paris

Doyen's reputation continued to grow, and he became an influential figure within the Royal Academy. In 1776, he was appointed Professor at the Academy, a role that involved teaching and guiding the next generation of artists. His studio would have attracted aspiring painters eager to learn from his mastery of composition and technique. One such artist who sought his counsel was the young Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, who would become one of the most celebrated portrait painters of her era. She recalled seeking Doyen's advice on her early works, a testament to his respected position. Another student, Louis Bertin, also benefited from Doyen's instruction, eventually becoming a member of the Academy himself.

Royal patronage also came Doyen's way. In 1773, he was appointed "Premier Peintre" (First Painter) to the Comte d'Artois (the future King Charles X) and the Comte de Provence (the future King Louis XVIII), brothers of King Louis XVI. This prestigious appointment signified high favor and likely brought further commissions and a stable income.

Despite his successes, Doyen's style sometimes faced criticism. As artistic tastes began to shift more decisively towards the clarity, restraint, and moralizing severity of Neoclassicism, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David, Doyen's more dramatic and emotionally charged Baroque-influenced style could be perceived by some as overly theatrical or "romanticized." The term "romanticized" in this context likely referred to an emphasis on emotion and dramatic effect that contrasted with the cool rationalism increasingly favored by Neoclassical proponents. Nevertheless, Doyen continued to receive important commissions and remained a respected figure. He was part of a circle of artists that included figures like the landscape and marine painter Joseph Vernet and the architectural painter Pierre-Antoine de Machy.

The French Revolution and a New Chapter in Russia

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 brought profound upheaval to French society and its artistic institutions. The Royal Academy was eventually suppressed, and many artists found their careers and lives disrupted. During the early, turbulent years of the Revolution, Doyen played a role in the preservation of France's artistic heritage. He was involved with the efforts, spearheaded by Alexandre Lenoir, to salvage sculptures and architectural fragments from churches and aristocratic residences that were being vandalized or destroyed. These salvaged items were gathered at the former convent of the Petits-Augustins, which would later become the Musée des Monuments Français, a crucial early step in the formation of national museum collections.

As the Revolution became more radical, particularly during the Reign of Terror, the situation for artists associated with the Ancien Régime became precarious. Like many others, Doyen sought opportunities elsewhere. He received an invitation from Empress Catherine the Great of Russia to come to Saint Petersburg. Catherine was a renowned patron of the arts and sciences, actively seeking to bring European culture and talent to her rapidly modernizing empire.

Doyen accepted the invitation and emigrated to Russia in 1791 or 1792. He was welcomed at the Imperial court and appointed a professor at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts. In Russia, he continued to work as a painter, undertaking commissions for the imperial family and the Russian nobility. His works in Russia likely included historical paintings, allegories, and possibly decorative schemes for imperial palaces. He would have brought his French academic training and his grand style to a new cultural context, contributing to the ongoing Westernization of Russian art. He would have been a contemporary of prominent Russian painters like Dmitry Levitzky and Vladimir Borovikovsky, who were defining a distinct Russian school of portraiture.

Final Years and Lasting Legacy

Gabriel-François Doyen spent the remainder of his life in Russia. After Catherine the Great's death in 1796, he continued to find patronage under her successor, Paul I, and then Alexander I. He died in Saint Petersburg in 1806, having witnessed the dramatic end of one era and the dawn of another, both in his native France and his adopted Russia.

Doyen's legacy is that of a highly skilled and ambitious painter who excelled in the "grand manner" of historical and religious art. His style represents a powerful continuation of the Baroque tradition, infused with a dramatic intensity and emotional depth that was distinct from the prevailing Rococo charm of many of his contemporaries. While the rise of Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on stoic virtue and linear clarity, eventually overshadowed his more painterly and theatrical approach, Doyen's major works, such as The Miracle of the Ardents, remain compelling examples of late Baroque religious painting in France.

He was a transitional figure, whose career bridged the gap between the Rococo and Neoclassicism. His commitment to serious, elevated themes, his mastery of complex compositions, and his ability to convey powerful emotions ensure his place in the history of French art. His decision to refuse the "Swing" commission speaks to an artistic integrity and a preference for subjects of greater import, aligning him with the more didactic and moralizing trends that gained traction in the latter half of the 18th century. Furthermore, his tenure in Russia contributed to the dissemination of French artistic traditions abroad, playing a part in the broader European cultural exchange of the period. Though perhaps not as widely known today as Fragonard or David, Gabriel-François Doyen was a formidable talent whose works offer a vivid insight into the artistic ambitions and shifting tastes of a fascinating and transformative century.