Carlo Maratta stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Italian art during the latter half of the seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries. Dominating the Roman school of painting, he forged a distinctive style that skillfully blended the High Baroque's dynamism with a refined classicism inherited from Renaissance masters. His long and prolific career saw him become the most sought-after painter in Rome, enjoying papal patronage, international acclaim, and a lasting influence on subsequent generations of artists. This exploration delves into the life, work, and legacy of a painter whose art defined an era.

Early Life and Formative Years in Rome

Carlo Maratta, sometimes spelled Maratti, entered the world in Camerano, located in the Marche region of Italy, which was then part of the Papal States. While sources slightly differ, his birth date is generally accepted as either May 13th or May 15th, 1625. Born into a family originally from Dalmatia, his artistic inclinations became apparent early on. Recognizing his potential, his family made the crucial decision to send him to Rome in 1636, when he was merely eleven years old. This move placed him at the very heart of the European art world.

Upon arriving in Rome, the young Maratta entered the prestigious studio of Andrea Sacchi. Sacchi was a leading proponent of the classical tradition in Roman Baroque painting, himself influenced by the Bolognese school, particularly the works of Annibale Carracci and his followers like Domenichino. Sacchi's studio provided Maratta with a rigorous education grounded in drawing, composition, and the study of classical antiquity and High Renaissance masters, most notably Raphael.

Maratta remained closely associated with Sacchi's workshop for an extended period, essentially until Sacchi's death in 1661. This long apprenticeship was profoundly formative. Sacchi imparted not only technical skills but also an artistic philosophy emphasizing clarity, order, and decorum, principles derived from the classical tradition championed by artists like Raphael and Nicolas Poussin, who was also active in Rome. Maratta absorbed these lessons deeply, forming the bedrock of his future artistic direction.

Beyond Sacchi's direct tutelage, the vibrant artistic environment of Rome itself served as a crucial classroom. Maratta studied the works of the great masters firsthand. He was particularly drawn to the grace and compositional harmony of Raphael, whose influence would remain a constant throughout his career. He also absorbed lessons from the Carracci family, especially Annibale Carracci, whose Farnese Gallery ceilings represented a benchmark for monumental decorative painting. Furthermore, the rich colours and emotional intensity of artists like Guido Reni left their mark on his developing sensibility. Even the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio, though representing a different stylistic pole, was part of the complex artistic tapestry Maratta navigated.

The Development of a Style: The Grand Manner

Carlo Maratta's mature style is best characterized as Late Baroque Classicism, often referred to as the "Grand Manner." This approach sought a synthesis between the structured, idealized forms of classicism, epitomized by Raphael and the Bolognese school (Annibale Carracci, Domenichino, Guido Reni), and the dynamic energy, rich colour, and emotional appeal characteristic of the High Baroque, exemplified by artists like Pietro da Cortona and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Maratta successfully navigated this artistic terrain, creating a style that was both noble and accessible.

His compositions are marked by clarity, balance, and a sense of order. Figures are typically arranged in stable, often pyramidal or triangular groupings, recalling High Renaissance precedents. Yet, these compositions are rarely static; Maratta infused them with a gentle movement and rhythmic flow. Drapery is handled with elegance, falling in broad, sculptural folds that define the underlying form while adding visual interest and a sense of grandeur.

Maratta possessed exceptional skill as a draughtsman, a foundation laid during his years with Sacchi. His figures are well-proportioned, anatomically sound, and possess a graceful solidity. He excelled at rendering idealized human forms, imbuing them with a sense of dignity and poise. While adhering to classical ideals of beauty, his figures are not cold or remote; they convey emotion with subtlety and restraint, achieving a balance between decorum and expressiveness.

His use of colour and light further distinguishes his style. Maratta employed a rich but harmonious palette, often favouring clear, luminous hues. His colours are less turbulent than those of some High Baroque contemporaries but possess a warmth and vibrancy that enhances the emotional resonance of his scenes. Light is used strategically to model forms, create atmosphere, and direct the viewer's attention, often falling gently across the main figures while leaving peripheral areas in softer shadow. This controlled chiaroscuro avoids the stark drama of Caravaggio but effectively enhances the three-dimensionality and emotional focus of his work.

This carefully constructed style, emphasizing clarity, idealization, harmonious composition, and controlled emotion, became the dominant mode in Roman painting during the late seventeenth century. It offered an alternative to the more exuberant High Baroque style of Pietro da Cortona, appealing to patrons who favoured restraint and classical decorum. Maratta became the leading exponent of this classical trend, setting the standard for academic painting in Rome.

Major Themes and Religious Works

Religion formed the cornerstone of Carlo Maratta's artistic output. Living and working in Rome, the centre of the Catholic Church, he received numerous commissions for altarpieces, devotional paintings, and large-scale decorative cycles for churches and papal residences. His particular aptitude for religious subjects, especially depictions of the Madonna and Child, earned him immense popularity and the affectionate nickname "Carluccio delle Madonne" (Little Carlo of the Madonnas).

His Madonnas are celebrated for their tender beauty, serene dignity, and gentle maternal affection. Maratta drew heavily on the precedent of Raphael, creating idealized yet human figures that resonated deeply with contemporary piety. These works, often produced in various versions and copies by his workshop due to high demand, showcase his ability to blend classical grace with warm sentiment. Examples like the Rest on the Flight into Egypt demonstrate his skill in creating harmonious compositions filled with tranquil emotion and beautifully rendered figures set within idyllic landscapes.

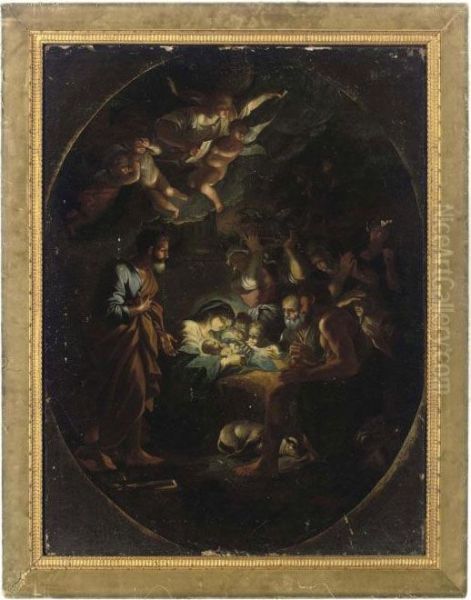

One of his significant early commissions, secured through the influence of Andrea Sacchi, was The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1650) for the church of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami in Rome. This work already displayed the hallmarks of his developing style: a clear composition, graceful figures inspired by classical and High Renaissance models, and a soft, atmospheric lighting. It marked an important step in establishing his reputation as an independent master.

A major undertaking that solidified his position was the commission from Pope Alexander VII Chigi for a large painting in the Baptistery of St. Peter's Basilica: Constantine Ordering the Destruction of Pagan Idols (completed c. 1655, though based on earlier designs). This work, part of a larger decorative scheme, perfectly aligned with the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on the triumph of Christianity. Maratta handled the complex historical subject with clarity and dramatic force, demonstrating his mastery of large-scale narrative composition and his ability to convey ideological messages through powerful imagery.

Perhaps his most famous altarpiece is The Assumption of the Virgin with Doctors of the Church for the Cybo Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome (c. 1686). This monumental work exemplifies his mature Grand Manner style. The composition is dynamic yet balanced, leading the eye upwards towards the ascending Virgin, who is depicted with ethereal grace. Below, the robust figures of the Church Fathers react with awe and devotion. The rich colours, skillful handling of light, and expressive figures combine to create a powerful statement of faith and artistic mastery.

Throughout his career, Maratta continued to produce numerous altarpieces and devotional images for Roman churches and patrons across Italy and Europe. His consistent ability to render sacred subjects with dignity, clarity, and emotional resonance made him the preeminent religious painter of his time in Rome.

Portraiture and Other Commissions

While primarily renowned for his religious paintings, Carlo Maratta was also an accomplished portraitist. He brought the same classical refinement and psychological insight to his depictions of popes, cardinals, aristocrats, and fellow artists. His portraits are characterized by their dignified presentation, careful attention to likeness, and ability to convey the sitter's status and personality through pose, expression, and the rendering of rich fabrics and accessories.

One of his most notable portraits is that of Pope Clement IX Rospigliosi (c. 1669). Maratta captures the pontiff with a blend of authority and gentle introspection, using subtle modeling and a warm palette. He also painted the influential art critic and historian Giovanni Pietro Bellori (c. 1672), who would later become his biographer. This portrait conveys Bellori's intellectual gravity and scholarly demeanor. These works demonstrate Maratta's skill in capturing not just physical features but also the inner life and social standing of his subjects.

Beyond easel paintings and portraits, Maratta engaged in other artistic activities. He was involved in large-scale decorative projects, often collaborating with other artists. For instance, he worked alongside painters like Francesco Cozza and Domenico Maria Canuti on the decoration of the Palazzo Altieri in Rome during the 1670s, contributing to the elaborate frescoes that adorned its grand interiors. These projects showcased his ability to work within larger architectural contexts.

An unusual but significant aspect of his oeuvre was his work designing and painting decorative panels for night clocks. These elaborate timepieces, popular among the Roman elite in the mid-to-late seventeenth century, featured translucent panels illuminated from behind by an oil lamp. Maratta created exquisite miniature paintings, often depicting mythological or allegorical scenes, for these clock faces. These small-scale works demonstrate his versatility and his mastery of delicate detail and luminous colour effects, contributing a unique element to Baroque decorative arts.

His involvement in diverse commissions, from monumental altarpieces to intimate portraits and decorative clock faces, highlights Maratta's versatility and his central role in the artistic life of Rome. He catered to a wide range of patrons and artistic needs, consistently applying his refined classical style across different scales and media.

Patronage and Recognition

Carlo Maratta's career was marked by extraordinary success and widespread recognition, fueled by powerful patronage from the highest levels of Roman society. His ability to satisfy the prevailing taste for classical decorum combined with Baroque sensibility made him the favoured artist of popes, cardinals, and the Roman aristocracy for several decades.

His relationship with Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi), which began with the commission for the St. Peter's Baptistery, proved highly beneficial. Alexander VII was a significant patron of the arts, overseeing major projects by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and others, and his support helped elevate Maratta's status. Subsequent popes also favoured him. Pope Clement IX Rospigliosi commissioned his portrait, and later, Pope Clement X Altieri entrusted him with significant roles, including work at the Palazzo Altieri.

This papal favour culminated in significant honours. In 1704, Pope Clement XI Albani bestowed upon Maratta the prestigious title of Knight of the Order of Christ. This knighthood was a significant mark of distinction, recognizing his preeminence in the Roman art world and his contributions to religious art. It solidified his social standing alongside his artistic reputation.

Maratta's fame extended beyond Rome and Italy. His works were sought after by collectors and patrons across Europe. His reputation reached the French court, a major centre of artistic patronage under King Louis XIV. In recognition of his international stature, Maratta was appointed principal painter to Louis XIV in 1707, although he remained based in Rome. This honorary title underscored his position as one of Europe's leading artists.

His studio became a major centre of production, employing assistants to help meet the high demand for his work and to produce copies and variations of his most popular compositions, particularly his Madonnas. This workshop system, common among successful Baroque artists, allowed Maratta to maintain a prolific output while ensuring a consistent quality associated with his name. His commercial success was commensurate with his critical acclaim, making him a wealthy and influential figure.

The combination of consistent high-level patronage, official honours, international recognition, and commercial success cemented Carlo Maratta's position as the undisputed leader of the Roman school of painting in the late Baroque period.

The Accademia di San Luca and Teaching

Beyond his personal artistic practice, Carlo Maratta played a significant role in the institutional art life of Rome through his involvement with the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of Saint Luke). This prestigious institution, the official academy for artists in Rome, served as a centre for training, discussion, and the promotion of artistic standards. Maratta's long association with the Academy culminated in his election as its Principe (Principal or President) in 1664, a position he held again in later years.

As Principe, Maratta was responsible for guiding the Academy's direction and upholding its artistic principles. Given his own artistic inclinations and training under Sacchi, he championed a curriculum based on the classical tradition. This involved emphasizing the importance of drawing (disegno), the study of anatomy and perspective, copying classical sculptures, and emulating the works of High Renaissance masters like Raphael and contemporary classicists like Poussin and his own teacher, Sacchi.

His leadership reinforced the classical current within Roman Baroque art, providing an institutional counterweight to the more exuberant styles. The Academy under his influence promoted ideals of order, clarity, decorum, and idealized beauty. While the provided sources indicate no specific list of documented pupils directly trained within his personal studio, his influence as head of the Academy was pervasive. He shaped the training and artistic outlook of a generation of younger artists studying in Rome.

His commitment to education and the preservation of artistic heritage extended to practical conservation efforts. Notably, he was involved in the restoration of Raphael's famous frescoes in the Vatican Stanze and the Villa Farnesina. This work demonstrated his deep reverence for Raphael and his technical understanding of fresco painting, further solidifying his role as a guardian of the classical tradition.

Through his leadership at the Accademia di San Luca and his restoration work, Maratta actively promoted the classical ideals that underpinned his own art. He helped ensure the continuation of this tradition within the Roman school, influencing the direction of painting in the city well into the eighteenth century.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Carlo Maratta navigated a complex web of relationships within the bustling Roman art world. His most significant connection was undoubtedly with his teacher, Andrea Sacchi. Their bond extended beyond a typical master-pupil relationship; they shared a deep artistic affinity rooted in classical principles and maintained a close friendship and professional association until Sacchi's death. Sacchi's support was instrumental in launching Maratta's independent career.

Maratta operated in an environment populated by artistic giants. While his style offered a more restrained alternative to the High Baroque dynamism of Pietro da Cortona or the dramatic intensity of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture and architecture, he was certainly aware of their work and competed for some of the same prestigious commissions. His classicizing approach aligned him more closely with the legacy of artists like Domenichino and the French painter Nicolas Poussin, who spent much of his career in Rome championing classical ideals.

He collaborated with other painters on large decorative projects. His work alongside Francesco Cozza and Domenico Maria Canuti at the Palazzo Altieri indicates a professional network and the ability to integrate his work within larger collaborative schemes. These collaborations were common in the execution of extensive fresco cycles in palaces and churches.

A crucial figure in Maratta's circle was Giovanni Pietro Bellori, the leading art theorist, critic, and biographer of the period. Bellori championed the classical ideal in art and saw Maratta as the leading contemporary exponent of this tradition, the rightful heir to Raphael and Annibale Carracci. Bellori wrote an influential biography of Maratta, published posthumously, which cemented the artist's reputation and interpreted his career through a classicizing lens. Their relationship appears to have been close, evidenced by Maratta's portrait of Bellori. However, some sources suggest potential underlying tensions, possibly related to Bellori's own theoretical biases, such as his controversial omission of Caravaggio from his influential Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1672).

Maratta's dominance in Rome meant he inevitably influenced many younger artists, even if specific student names are scarce in the provided records. His style became the benchmark for academic painting. Artists visiting Rome from other parts of Italy and Europe studied his works. For example, the German-born English court painter Sir Godfrey Kneller is known to have been influenced by Maratta's style during his time in Italy, incorporating elements of the Grand Manner into his own portraiture.

His interactions – with his teacher, patrons, collaborators, critics like Bellori, and the broader artistic community including figures like Baciccio (Giovanni Battista Gaulli), another prominent ceiling painter – shaped his career and solidified his central position in the Roman art scene for nearly half a century.

Anecdotes and Working Methods

While historical records often focus on major commissions and stylistic analysis, glimpses into Carlo Maratta's personality and working methods emerge from anecdotes preserved by contemporaries, particularly his biographer Bellori. These stories offer a more personal perspective on the artist.

One well-known anecdote highlights his dedication and perhaps his subconscious creative process. Bellori recounts that Maratta often worked late into the night. His brother reportedly found him asleep but still holding his drawing implement. When questioned in his sleep about what he was doing, Maratta supposedly murmured, "Sto disegnando" ("I am designing" or "I am drawing"). This story suggests an artist deeply immersed in his work, whose creative mind continued to refine ideas even during rest, possibly using the quiet night hours to perfect sketches conceived during the day.

The nickname "Carluccio delle Madonne" speaks volumes about his public perception and artistic focus. While seemingly affectionate, it underscores his particular fame for depicting the Virgin Mary. Some later interpretations might speculate about his relationship with models, but historical sources emphasize his piety and the serene, idealized nature of these depictions. The nickname more likely reflects his mastery and the popular appeal of his gentle, graceful Madonnas, rather than any documented personal scandals. There is no concrete evidence suggesting inappropriate relationships with his models; the focus remained on the devotional quality of the art itself.

His involvement in restoring Raphael's frescoes reveals not just reverence for the master but also a practical, hands-on approach to his craft and its history. This task required significant technical skill and sensitivity, reflecting a deep understanding of Renaissance techniques. It positioned him not just as a creator but as a custodian of artistic heritage.

His long tenure as Principe of the Accademia di San Luca suggests strong leadership qualities and the respect he commanded among his peers. Running an institution like the Academy required administrative skill and diplomacy, alongside artistic authority. His repeated election to the post indicates he was effective in this role.

These fragments paint a picture of a dedicated, highly skilled, and respected artist, deeply committed to his craft and the classical tradition. He appears as a serious figure, whose life revolved around his art, his patrons, and the institutions that shaped the Roman art world.

Later Life and Death

Carlo Maratta enjoyed a remarkably long and productive life, remaining active as an artist well into his eighties. His dominance over the Roman art scene continued largely unchallenged until his final years. He maintained his workshop, continued to receive commissions, and held a position of immense respect within the artistic community. His later works generally maintain the high standards of his mature period, characterized by refined classicism, technical polish, and emotional restraint.

His influence persisted through his role at the Accademia di San Luca and the continued demand for his paintings. He had successfully established his brand of Late Baroque Classicism as the prevailing style in Rome, a style that would bridge the gap towards the emerging Neoclassicism of the mid-eighteenth century, even as tastes began to slowly shift.

Carlo Maratta died in Rome on December 15, 1713, at the venerable age of 88. His death marked the end of an era in Roman painting. He was afforded the honour of being buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, a prestigious church designed by Michelangelo within the ancient Baths of Diocletian. His tomb monument, designed by his daughter Faustina Maratta (who was also a poet and painter, though less famous) and executed by sculptor Francesco Moratti, stands as a testament to the high esteem in which he was held.

His passing left a void in the Roman art world. While he had influenced many, no single artist immediately emerged with the same level of authority or widespread acclaim. His death coincided with a gradual shift in artistic sensibilities across Europe, but his legacy continued to shape academic practice for some time.

Legacy and Influence

Carlo Maratta's legacy is significant and multifaceted. For nearly half a century, he was the leading painter in Rome, defining the dominant artistic style of the Late Baroque period in the city. His synthesis of High Renaissance classicism (particularly Raphael's grace) with Baroque elements created a refined, elegant, and emotionally accessible "Grand Manner" that appealed widely to patrons and artists alike.

His influence was profound, particularly through his role as Principe of the Accademia di San Luca. He institutionalized a classical approach to art education, emphasizing drawing, study of the antique, and emulation of masters like Raphael and the Carracci. This academic classicism became the foundation for artistic training in Rome and influenced academies elsewhere in Europe. Many artists passing through Rome absorbed his style, disseminating it internationally. Sir Godfrey Kneller's adoption of Maratta's portrait style in England is one prominent example.

His religious paintings, especially his Madonnas, became iconic representations of Late Baroque piety. Their blend of idealized beauty and tender sentiment set a standard for devotional art that was widely imitated. His large-scale altarpieces and historical paintings demonstrated how the classical tradition could be adapted to serve the narrative and didactic needs of the Counter-Reformation Church.

However, Maratta's reputation experienced fluctuations after his death. With the rise of Neoclassicism in the mid-to-late eighteenth century, spearheaded by figures like Anton Raphael Mengs and Jacques-Louis David, Maratta's style, along with much Baroque art, came to be seen by some critics as lacking the perceived purity and severity of true classicism. His work was sometimes criticized for being overly sweet or formulaic.

Nevertheless, the twentieth century saw a scholarly reassessment of Baroque art, leading to a renewed appreciation of Maratta's achievements. Art historians recognized his crucial role in bridging the High Baroque and Neoclassicism, his technical mastery, and the quality and influence of his vast output. He is now firmly established as a major figure in Italian art history, the last great master of the Roman Baroque classical tradition. His works remain central to understanding the complex artistic landscape of late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century Europe.

Conclusion

Carlo Maratta's long career represents the culmination of the classical tradition within the Roman Baroque. From his rigorous training under Andrea Sacchi to his decades-long reign as Rome's most sought-after painter, he forged a style characterized by grace, clarity, and decorum, skillfully blended with Baroque colour and sentiment. His Madonnas, altarpieces, and portraits set the standard for artistic excellence, earning him papal honours and international renown. Through his leadership at the Accademia di San Luca, he profoundly influenced artistic education and practice. While his reputation ebbed and flowed with changing tastes, Carlo Maratta remains an indispensable figure for understanding the transition from the dynamism of the High Baroque to the ordered world of Neoclassicism, leaving behind a legacy of refined beauty and enduring influence.