Georg Schrimpf stands as a significant, if sometimes understated, figure within the diverse landscape of early 20th-century German art. Primarily associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, his work offers a distinct counterpoint to the biting satire of some of his contemporaries. Schrimpf's art is characterized by a profound sense of calm, a lyrical classicism, and a deep connection to themes of nature, domesticity, and the enduring human spirit. His journey from a working-class background to a recognized artist, and his subsequent persecution under the Nazi regime, paints a vivid picture of the turbulent times in which he lived and worked.

Early Life and Formative Experiences

Born on February 13, 1889, in Munich, Germany, Georg Schrimpf's early life was marked by hardship and a restless spirit. His stepfather's disapproval of his artistic inclinations led him to leave home at a young age. Between 1905 and 1909, he embarked on a period of itinerant wandering across Europe, taking on various manual labor jobs in Belgium, France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. This period of poverty and direct experience with the working class profoundly shaped his worldview and instilled in him a critical perspective on capitalist society, a sentiment that would subtly inform his later artistic output.

In 1909, Schrimpf settled for a time in Munich, a vibrant artistic hub. There, he became involved with an anarchist group called "Die Tat" (The Deed), founded by Emil Schaub. This association exposed him to radical political ideas and, significantly, to the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis, which was beginning to permeate intellectual circles. Though largely self-taught as an artist, these early exposures to diverse ideologies and social realities provided a rich, albeit unconventional, foundation for his artistic development.

A pivotal encounter occurred in 1911 when Schrimpf met the writer Oskar Maria Graf. Graf, who would also become a notable figure in German literature, became a close friend and an important supporter of Schrimpf's artistic ambitions. This friendship provided intellectual companionship and encouragement during a crucial formative period. By 1913, Schrimpf had returned to Munich with a growing determination to pursue art seriously, eventually establishing his own studio.

Artistic Beginnings and Emergence

Schrimpf's formal entry into the art world began to solidify around 1915. This year marked his first significant exhibition, showcasing his works at Herwarth Walden's renowned Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin. Der Sturm was a leading avant-garde gallery, pivotal in promoting Expressionism and other modern art movements, and exhibiting there provided Schrimpf with crucial visibility. His early works from this period, such as Zwei Frauen unter Bäumen (Two Women Under Trees, 1915), often featured simplified forms, a muted palette, and a certain graphic quality, sometimes hinting at influences from Cubism or the lingering spirit of Post-Impressionism.

In 1916, Schrimpf married the painter and graphic artist Maria Uhden. Her own artistic pursuits and their shared life undoubtedly influenced his thematic concerns. Following their marriage, and especially after the birth of their child, themes of motherhood, family, and domestic harmony became increasingly prominent in his work. Uhden, an accomplished artist in her own right, was associated with the Expressionist circle, and her presence likely further immersed Schrimpf in the contemporary artistic dialogues of Munich and Berlin. Sadly, Maria Uhden passed away in 1918, a loss that deeply affected Schrimpf.

The tumultuous political climate of post-World War I Germany also left its mark. In 1918, Schrimpf joined the German Communist Party (KPD) and was involved in the revolutionary activities surrounding the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic. While his direct political activism was relatively brief, his leftist sympathies would later have severe consequences for his career.

The New Objectivity and Schrimpf's Distinctive Voice

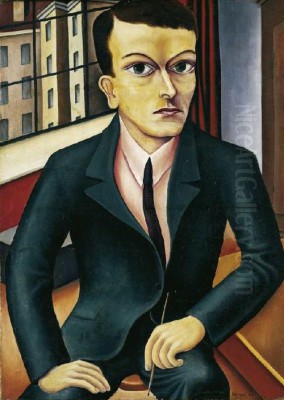

The 1920s witnessed the rise of the Neue Sachlichkeit, a movement that emerged as a reaction against the emotionalism and abstraction of Expressionism. It called for a return to figuration, a sober and objective depiction of reality, often with a critical or satirical edge. The movement was broadly divided into two wings: the Verists, like George Grosz and Otto Dix, whose work was characterized by harsh social critique and often grotesque portrayals of Weimar society; and the Classicists, to which Schrimpf belonged, alongside artists like Alexander Kanoldt and Carlo Mense. This latter group favored a more serene, timeless, and often idealized representation of subjects, drawing inspiration from early Renaissance masters and a sense of classical order.

Schrimpf became one of the leading figures of this Classicist wing. His paintings from this period are distinguished by their clarity of form, smooth application of paint, and a palette often dominated by gentle, earthy tones. He frequently depicted tranquil landscapes, often of his native Bavaria, imbued with an almost dreamlike stillness. Figures, particularly women and children, are rendered with a tender simplicity, exuding an aura of quiet contemplation and inner peace. Works like Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child, 1923) and Schlafendes Mädchen (Sleeping Girl, 1926) exemplify this focus on intimate, harmonious scenes.

A recurring motif in Schrimpf's work is the window or the balcony, as seen in Mädchen am Fenster (Girl at the Window, 1927) and Mädchen auf dem Balkon (Girl on the Balcony). These compositions often feature figures gazing outwards, creating a sense of introspection and a subtle boundary between the inner, private world and the external reality. The window acts as a frame, both literally and metaphorically, suggesting a longing for something beyond the immediate, or a peaceful observation of the world.

Influences and Artistic Style

While largely self-taught, Schrimpf was a keen observer and absorbed various influences. His style shows a clear affinity with the clarity and formal purity of early Italian Renaissance painters like Giotto or Piero della Francesca. This connection was not unique to Schrimpf; many artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit looked to pre-High Renaissance art for models of objective representation and compositional stability.

More directly, Schrimpf was influenced by the Italian "Pittura Metafisica" (Metaphysical Painting) movement, particularly the works of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. Carrà, after his Futurist phase, moved towards a style characterized by solid, sculptural forms and a sense of timeless stillness, which resonated with Schrimpf's own inclinations. The dreamlike, enigmatic quality found in de Chirico's paintings, with their stark perspectives and melancholic atmospheres, also finds echoes in the quiet intensity of Schrimpf's compositions. This Italian influence contributed to the "Magic Realism" aspect often associated with the Classicist wing of Neue Sachlichkeit, where everyday scenes are imbued with an unsettling or otherworldly quality.

Schrimpf's technique involved meticulous brushwork, creating smooth, almost enamel-like surfaces. He avoided expressive gestures, preferring a controlled application of paint that emphasized form and volume. His figures often have a sculptural quality, appearing solid and grounded, yet imbued with a gentle grace. The landscapes are typically ordered and harmonious, reflecting an idealized vision of nature rather than a strictly realistic depiction. This idealization, however, was not purely escapist; it can be interpreted as a yearning for peace and stability in a deeply troubled era.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Georg Schrimpf's oeuvre, each encapsulating different facets of his artistic vision.

Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child, 1923) is a quintessential example of his focus on maternal themes. The painting depicts a mother tenderly holding her child, their forms simplified and rounded, conveying a sense of protective love and tranquility. The setting is often a simple, almost rustic interior or a serene landscape, emphasizing the universal and timeless nature of the maternal bond. This theme, deeply personal after the birth of his own child and the loss of his wife Maria Uhden, became a recurring motif, representing an ideal of harmony and natural order.

Mädchen am Fenster (Girl at the Window, 1927), now housed in the Kunstmuseum Basel, is considered one of his museum-quality masterpieces. It features two young girls, one looking out a window, the other slightly behind her, perhaps looking at her companion or also towards the unseen view. The composition is balanced and calm, the figures rendered with Schrimpf's characteristic smooth finish and gentle modeling. The window motif here evokes a sense of quiet contemplation, a threshold between an intimate interior space and the wider world, hinting at youthful dreams or a pensive observation of life.

Am Morgen (In the Morning, 1936) is another celebrated work, again featuring a figure near a window or on a balcony, a common setting for Schrimpf. These scenes often capture a moment of quiet solitude, the soft light of morning enhancing the peaceful atmosphere. The careful arrangement of architectural elements and the poised stillness of the figures contribute to the overall sense of order and serenity that Schrimpf sought in his art.

His earlier work, Zwei Frauen unter Bäumen (Two Women Under Trees, 1915), shows a more graphic, stylized approach, with simplified, almost block-like forms that suggest an engagement with early modernist trends like Cubism or the woodcut tradition. Comrades (1915), described in some sources as depicting nude figures, likely also reflects these early explorations before he fully developed his signature Neue Sachlichkeit style. Even a work like Swineherd, which some contemporary critics found almost comically idyllic, demonstrates his commitment to depicting rural life, albeit through a romanticized and highly stylized lens.

Schrimpf and His Contemporaries

Georg Schrimpf was an active participant in the German art scene of the 1920s. He exhibited alongside other prominent figures of the Neue Sachlichkeit. His closest artistic allies were those in the Classicist camp, such as Alexander Kanoldt, with whom he shared an interest in meticulously rendered landscapes and still lifes, and Carlo Mense, whose figures also possessed a similar sculptural quality and serene demeanor. Other artists associated with this more idyllic or Magic Realist tendency included Heinrich Maria Davringhausen and Franz Radziwill, though Radziwill's work often had a more overtly unsettling or ominous undertone.

In contrast, the Verist wing of Neue Sachlichkeit, dominated by artists like George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter, pursued a far more aggressive and critical engagement with the social and political realities of the Weimar Republic. Their works often depicted the moral decay, corruption, and social inequalities of the era with biting satire and unflinching realism. Max Beckmann, another towering figure of the period, forged his own powerful path, often straddling Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit, his works filled with complex allegories and a profound sense of human suffering.

While Schrimpf's art did not engage in overt social critique in the manner of Grosz or Dix, its emphasis on harmony, order, and traditional values can be seen as an alternative response to the chaos and anxieties of the time. It offered a vision of solace and enduring beauty, a quiet resistance to the surrounding turmoil. He also maintained connections with artists from other movements, such as those associated with the Bauhaus, like Oskar Schlemmer, whose stylized and theatrical figures shared a certain formal clarity with Schrimpf's work, despite their different artistic aims.

The Shadow of National Socialism

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a dramatic and tragic turning point for modern art in Germany, and for Georg Schrimpf personally. Initially, Schrimpf's art, with its seemingly traditional subject matter and classical style, might have appeared less offensive to the Nazi regime than the more overtly critical or abstract works of other modernists. Indeed, for a brief period, his depictions of rural life and idealized German landscapes found some favor. He was even appointed as an extraordinary professor at the Staatliche Kunstschule (State Art School) in Berlin-Schöneberg in 1933.

However, this acceptance was short-lived. The Nazi cultural authorities soon launched a systematic campaign against modern art, which they branded "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art). This campaign targeted a wide range of artistic styles, including Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and even the Neue Sachlichkeit. Artists were condemned for being "un-German," "Jewish," "Bolshevik," or simply for deviating from the narrow, propagandistic aesthetic favored by the regime, which promoted a heroic, pseudo-classical realism.

Schrimpf's past association with the Communist Party and his connections to leftist intellectual circles, such as his friendship with Oskar Maria Graf (who himself became an outspoken critic of the Nazis and whose books were burned), made him a target. Despite the seemingly innocuous nature of his art, he was deemed politically unreliable. In 1937, he was dismissed from his teaching position at the Berlin art school. His works were confiscated from German museums, and some were included in the infamous "Entartete Kunst" exhibition of 1937, which aimed to ridicule and defame modern art. Artists like Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marc Chagall were among the many whose works suffered the same fate.

The persecution and professional ruin took a heavy toll on Schrimpf. His health deteriorated, and he died relatively young, on April 19, 1938, in Berlin, at the age of 49. His death occurred just as the Nazi cultural purge was reaching its peak, effectively silencing one of the gentler voices of German modernism.

Legacy and Reassessment

For many years after World War II, Georg Schrimpf's work, like that of many artists associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit who did not fit neatly into the narrative of heroic avant-garde resistance, was somewhat overlooked. The focus of art historical attention often fell on the more overtly radical or politically engaged figures of the Weimar era.

However, in recent decades, there has been a growing reassessment of the Neue Sachlichkeit in all its diversity, and Schrimpf's contribution has received renewed appreciation. His art is now recognized for its unique blend of classical serenity and subtle modern sensibility. His paintings offer a poignant counter-narrative to the more common depictions of Weimar Germany as solely a period of decadence and crisis. They speak to a persistent human desire for peace, order, and connection to nature, even in the midst of profound social and political upheaval.

Museums and galleries worldwide now include his works in exhibitions on German modernism and the Neue Sachlichkeit. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their quiet emotional depth, and their distinctive place within the artistic currents of the early 20th century. Artists like Christian Schad, another prominent figure of Neue Sachlichkeit known for his cool, precise portraits, also contribute to this broader understanding of the movement's varied expressions.

Schrimpf's legacy lies in his ability to create images of enduring calm and beauty that transcend the immediate turmoil of his times. His figures, often lost in thought or quietly observing the world, invite viewers into a space of contemplation. His landscapes, while idealized, evoke a deep sense of belonging and a connection to the natural world. In a world increasingly saturated with noise and conflict, the serene and ordered vision of Georg Schrimpf continues to resonate, offering a timeless message of peace and the quiet dignity of the human spirit. His relatively short but impactful career serves as a reminder of the diverse artistic responses to a complex historical period and the enduring power of art to find beauty and meaning even in challenging circumstances.