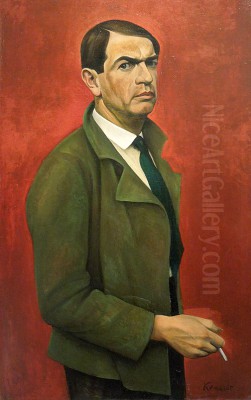

Alexander Kanoldt stands as a significant figure in 20th-century German art, primarily recognized for his pivotal role within the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement. Born in Karlsruhe, Germany, on September 29, 1881, and passing away in Berlin on January 24, 1939, Kanoldt's artistic journey traversed several key developments in modern European art. His work, particularly his meticulously rendered still lifes and landscapes, embodies a unique blend of precise realism and an underlying sense of stillness and enigma, often categorized under the umbrella of Magic Realism. His career reflects the turbulent artistic and political landscape of Germany from the late Wilhelmine era through the Weimar Republic and into the early years of the Third Reich.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Alexander Kanoldt's immersion in the art world began at birth. He was the son of Edmund Kanoldt, a respected landscape painter associated with the late Romantic tradition. This familial connection undoubtedly provided an early exposure to artistic practice and aesthetics. Growing up in Karlsruhe, a city with a strong artistic tradition, further nurtured his inclinations. He initially pursued studies in decorative painting at the local School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule).

His formal art education continued at the prestigious Karlsruhe Academy of Fine Arts (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Karlsruhe). There, he studied under artists like Ernst Schurth and, notably, Friedrich Fehr, a painter known for his naturalist approach. This academic training provided Kanoldt with a solid foundation in traditional drawing and painting techniques, emphasizing careful observation and skilled execution – elements that would remain central to his work even as his style evolved. His early works from this period reflect the influences of late Impressionism and Symbolism prevalent at the turn of the century.

Munich Years and Avant-Garde Involvement

A crucial turning point in Kanoldt's career came in 1908 when he moved to Munich. At that time, Munich, particularly its Schwabing district, was a vibrant hub of artistic innovation, attracting artists from across Germany and Europe. Kanoldt quickly integrated into the city's progressive art circles. In 1909, he became a co-founder of the influential Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM), or New Artists' Association of Munich.

The NKVM served as a crucial platform for artists seeking alternatives to the established Secession movements and Impressionism. Kanoldt found himself in the company of pioneering figures who would soon shape the course of modern art, including Russian émigrés Wassily Kandinsky and Alexej von Jawlensky, along with German artists like Gabriele Münter, Marianne von Werefkin, and Adolf Erbsloh. The group organized exhibitions that showcased a diverse range of styles, moving towards greater expressiveness in color and form.

Although the NKVM was relatively short-lived, dissolving amidst internal disagreements in 1911, Kanoldt's involvement placed him at the forefront of the burgeoning Expressionist movement. When Kandinsky and Franz Marc broke away to form the core of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), Kanoldt maintained connections with this circle. He participated in the second Blue Rider exhibition in 1912, demonstrating his alignment with the avant-garde's push towards spiritual and formal innovation in art, even if his own path would eventually diverge from pure Expressionism. Other artists associated with this broader milieu included August Macke and Paul Klee.

Wartime Experiences and Stylistic Shifts

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly impacted Kanoldt, as it did for many artists of his generation. He served as an officer throughout the conflict, from 1914 to 1918. The direct experience of war often led artists to reassess their pre-war ideals and artistic approaches. For some, it reinforced a turn towards social critique; for others, like Kanoldt, it seemed to foster a desire for order, clarity, and a return to tangible reality, albeit viewed through a modern lens.

During and immediately after the war, Kanoldt's style began to consolidate. While his earlier work showed Post-Impressionist and Fauvist influences, likely absorbed through his Munich connections and potentially travels to France, he now moved towards a more structured and objective representation. Influences from French modernism remained, particularly the formal simplifications and emphasis on structure found in the work of artists like André Derain, and the geometric underpinnings of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. However, Kanoldt adapted these influences not towards abstraction, but towards a heightened, sharpened realism. This period marked the transition away from the expressive subjectivity of his earlier associations towards the cool precision that would characterize his mature style.

The Rise of New Objectivity and Magic Realism

The post-war years in Germany, coinciding with the establishment of the Weimar Republic, saw the emergence of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement. Coined by Gustav Hartlaub, director of the Mannheim Kunsthalle, for a seminal exhibition in 1925, the term encompassed a range of artistic responses reacting against the emotionalism and abstraction of Expressionism. It signaled a return to figurative art, characterized by sobriety, precision, and often a critical or detached view of contemporary reality.

Alexander Kanoldt emerged as one of the leading figures of this movement, particularly representing its more conservative, classicizing wing. This tendency, sometimes contrasted with the biting social critique of the Verist wing (represented by artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz), focused on meticulous rendering, smooth surfaces, and a sense of timeless order. Kanoldt, along with his close associate Georg Schrimpf, became strongly identified with this approach. His work was prominently featured in the 1925 Mannheim exhibition, solidifying his position within the movement.

Within New Objectivity, Kanoldt's style is often specifically described as Magic Realism. This term, also gaining currency in the 1920s (popularized by critic Franz Roh), denotes a style where everyday objects and scenes are depicted with extreme, almost photographic clarity, yet imbued with an unsettling, dreamlike, or mysterious atmosphere. The "magic" arises not from fantastical elements, but from the intense focus, the isolation of objects, the strange stillness, and the suggestion of hidden significance beneath the surface of the ordinary. Kanoldt's work perfectly exemplifies this tendency.

Focus on Still Life: The Core of Kanoldt's Oeuvre

Still life painting became the central genre through which Alexander Kanoldt explored and perfected his distinctive style. His still lifes are immediately recognizable for their precision, clarity, and air of profound quiet. He typically selected simple, everyday objects: potted plants (especially cacti and succulents with their strong geometric forms), ceramic vessels, boxes, fruit, and sometimes musical instruments or books. These items were arranged in carefully composed, often starkly lit settings.

Kanoldt rendered these objects with meticulous detail and a smooth, enamel-like finish that minimized visible brushwork. He employed sharp contrasts of light and shadow to emphasize the solidity and volume of forms, giving them an almost sculptural presence. Backgrounds were often simplified or abstracted, consisting of plain walls or empty spaces, which served to isolate the objects and enhance their enigmatic quality. There is a palpable sense of stillness and timelessness in these works; the objects seem frozen, removed from the flow of everyday life.

His representative works in this genre include Still Life XII (1920) and Still Life XI. Another notable example is Still Life with Books and Lilies (1916), now housed in the Kunsthalle Kiel. In paintings like Still Life I/Flower Pots, the humble subjects are elevated through intense scrutiny and formal rigor. Kanoldt treated each object with equal importance, arranging them in compositions that often emphasize geometric relationships and spatial clarity. This approach invites contemplation, suggesting metaphorical or philosophical meanings embedded within the mundane. While distinct in style, the quiet intensity might distantly echo the meditative focus found in the works of Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, another master of modern still life.

Landscapes and Other Works

While best known for his still lifes, Alexander Kanoldt also applied his characteristic style to landscape painting. His landscapes often depict architectural subjects, particularly views of Italian towns and villages, which he visited on several occasions. Olevano Romano, a town southeast of Rome popular with artists, was a recurring subject. These landscapes share the same qualities of sharp focus, clear light, geometric structure, and eerie stillness found in his still lifes. Buildings are rendered with precision, often under a stark, clear sky, devoid of human activity, creating a sense of timelessness and sometimes alienation.

Kanoldt was also active as a printmaker, primarily working in lithography. His prints often revisited themes from his paintings, translating his precise style into the graphic medium. Notable prints include Olevano V (1925), reflecting his Italian travels, and later works like Bergwelt / Welter (Mountain World / World, 1937). These prints allowed for wider dissemination of his imagery and demonstrate his consistent artistic vision across different media. His dedication to craftsmanship was evident in both his paintings and his graphic work.

Academic Career and Teaching

Beyond his studio practice, Alexander Kanoldt pursued an academic career. In 1925, he was appointed professor at the State Academy for Arts and Crafts (Staatliche Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe) in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). He later became its director. His appointment reflected his established reputation within the New Objectivity movement. However, his tenure in Breslau was marked by conflict. He reportedly clashed with the previous director, Oskar Moll, an artist associated with the circle of Henri Matisse, over the direction of the academy. These disagreements led to Kanoldt's resignation in 1931 or 1932.

Following his departure from Breslau, Kanoldt secured another prestigious position, becoming a professor at the Berlin University of the Arts (Vereinigte Staatsschulen für freie und angewandte Kunst, now Universität der Künste Berlin) in 1933. This appointment placed him in the heart of the German art world during a critical period. Alongside his teaching, in 1927, Kanoldt had also opened a private painting school and gallery in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Bavaria, providing another venue for teaching and exhibiting art. His academic career, however, was cut short by ill health, forcing him to retire from his Berlin post in 1936.

Navigating the Nazi Era

The rise of the National Socialist (Nazi) party to power in 1933 cast a long shadow over the German art world. The regime quickly implemented policies to control culture, denouncing most forms of modern art as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst) and promoting a state-sanctioned style based on idealized realism and nationalist themes. Artists associated with Expressionism, New Objectivity, Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction faced persecution, dismissal from teaching posts, bans on exhibiting or working, and confiscation of their art.

Alexander Kanoldt's situation during this period was complex and reflects the difficult choices faced by many artists. He had joined the NSDAP in 1932, before Hitler came to power. Following the Nazi takeover, he attempted to adapt his artistic style to align with the regime's preferences, shifting towards a more romanticized, less severe form of realism in some of his later works. This was likely an attempt to safeguard his career and continue working within the system.

Despite these efforts and his party membership, Kanoldt did not escape the "Degenerate Art" campaign entirely. In 1937, several of his earlier, more modern works were confiscated from German museums as part of the purge. This demonstrates the often arbitrary and unpredictable nature of Nazi cultural policy. His association with the pre-Nazi avant-garde and the inherent modernity of his precise, sometimes unsettling style likely made him suspect, regardless of his attempts to conform. Furthermore, provenance research has highlighted the complex histories of some artworks acquired during this era, including potential links to collections seized from Jewish owners, underscoring the ethically fraught context of the art market under Nazi rule. Kanoldt's experience illustrates the precarious position of artists navigating the demands of a totalitarian regime. Other artists associated with New Objectivity, like Christian Schad or Rudolf Schlichter, faced similar pressures, while figures like Max Beckmann chose exile.

Later Life and Legacy

Alexander Kanoldt's health declined in the late 1930s, leading to his retirement from teaching in 1936. He passed away in Berlin on January 24, 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II. In the immediate post-war decades, Kanoldt's work, along with much of the New Objectivity movement, received relatively little attention. The art world's focus shifted towards Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in Europe. New Objectivity was sometimes viewed critically, associated with the perceived failures of the Weimar Republic or tainted by the compromises some artists made during the Nazi era.

However, beginning in the later 20th century and continuing into the 21st, there has been a significant reassessment and renewed appreciation of German art from the interwar period. Exhibitions and scholarly research have highlighted the importance and diversity of the New Objectivity movement. Within this context, Alexander Kanoldt has been recognized as a key exponent of its classicizing tendency and a master of Magic Realism. His meticulous technique, his ability to imbue ordinary scenes with profound stillness and mystery, and his contribution to the visual language of the Weimar era are now widely acknowledged.

His works are held in major public collections in Germany and internationally, including the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, the Kunsthalle Kiel, the Berlinische Galerie, and the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum in Japan, among others. His paintings and prints continue to fascinate viewers with their combination of precise observation and subtle psychological depth.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Precision and Enigma

Alexander Kanoldt occupies a distinct and important place in the history of German modern art. As a co-founder of the NKVM and an early participant in the avant-garde circles of Munich, he was involved in the formative stages of Expressionism. However, his mature style found its definitive expression within the New Objectivity movement of the 1920s. His meticulously rendered still lifes and landscapes, characterized by sharp focus, smooth surfaces, clear light, and an atmosphere of profound stillness, define him as a leading practitioner of Magic Realism.

His art reflects a search for order and clarity in a tumultuous era, yet it avoids simple representation, instead imbuing the everyday with a sense of mystery and timelessness. While navigating the complex political pressures of his time, Kanoldt maintained a commitment to technical mastery and a unique artistic vision. Today, his work is valued for its formal rigor, its psychological resonance, and its significant contribution to the diverse landscape of European modernism between the World Wars. He remains a testament to the enduring power of precisely observed reality filtered through a distinct artistic sensibility.