George Bernard O'Neill stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art, particularly noted for his charming and detailed depictions of domestic life and rural England. Born in Ireland but spending his formative and professional years in London, O'Neill became a key member of the influential Cranbrook Colony and a popular painter whose works captured the sentiment and social nuances of the Victorian era. His career spanned a period of immense change, and his art provides a valuable window into the everyday world of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

George Bernard O'Neill was born in Dublin, Ireland, on July 17, 1828. He was the ninth of fifteen children born into a middle-class family. His father served as a military quartermaster, and while respectable, the family was not affluent. This necessitated that the children contribute to the household income from a relatively early age, instilling perhaps a sense of diligence and observation of everyday struggles and joys that would later inform his art.

In 1837, when George was about nine years old, the O'Neill family relocated to England, settling in London. This move proved pivotal for the young O'Neill's future artistic path. London, as the heart of the British Empire and a major centre for the arts, offered opportunities unavailable in Dublin at the time. He showed early promise and pursued formal art training, enrolling as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1845.

The Royal Academy was the preeminent institution for art education and exhibition in Britain. Studying there provided O'Neill with rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and composition, grounding him in the academic traditions of the time. He began exhibiting his work regularly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions starting in 1847, quickly making a name for himself within the London art scene.

Development of a Distinctive Style: Genre Painting and Influences

O'Neill specialised in genre painting – scenes of everyday life, often featuring domestic interiors, children at play, and moments of quiet rural activity. This focus aligned him with a strong tradition in British art, but he developed his own particular approach, marked by careful detail, warm sentiment, and an adept handling of light and shadow. His active period stretched across much of the latter half of the 19th century, with his most prolific and popular phase occurring between the 1850s and the 1870s.

His artistic style reveals a deep appreciation for the Dutch and Flemish Masters of the 17th century. Art historians note the influence of painters like Johannes Vermeer, known for his tranquil domestic scenes and mastery of light, and Frans Hals, celebrated for his lively portraiture. O'Neill admired their ability to elevate everyday subjects through technical skill and sensitive observation.

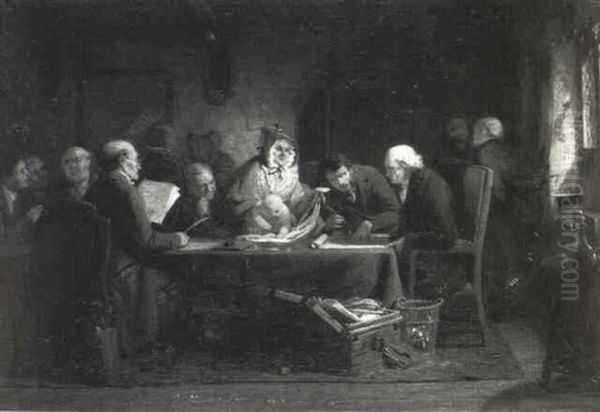

Furthermore, the compositional strategies and intimate settings in O'Neill's work often echo those of Dutch realists such as Pieter de Hooch. Like de Hooch, O'Neill frequently depicted figures within carefully rendered interior spaces, using doorways and windows to create depth and frame vignettes of domestic life. The influence of Rembrandt van Rijn can also be discerned in O'Neill's use of chiaroscuro, or strong contrasts between light and dark (sometimes referred to as tenebrism), to create mood and focus attention within his compositions.

O'Neill's paintings are characterized by their meticulous attention to detail – the textures of fabrics, the surfaces of furniture, the expressions on his figures' faces are all rendered with precision. He often populated his canvases with numerous figures and objects, aiming for a sense of lived-in reality. While this richness was generally appreciated, some contemporary critics occasionally found his compositions overly cluttered. However, the overall effect was typically one of warmth, cheerfulness, and relatable human emotion, which resonated strongly with Victorian audiences.

Key Works and Public Recognition

O'Neill achieved significant public recognition early in his career. A breakthrough came in 1852 with the exhibition of his painting The Foundling at the Royal Academy. This work depicted the poignant subject of an abandoned child being discovered or cared for, tapping into Victorian sensibilities regarding social issues, charity, and the vulnerability of childhood. The painting was highly praised, blending elements reminiscent of Old Master compositions with the sentimental appeal of its subject matter, firmly establishing O'Neill's reputation.

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, O'Neill produced many of his most characteristic and popular works. He excelled at capturing the world of children – their games, lessons, and interactions within the family circle. Scenes of cottage interiors, village gatherings, and quiet moments of reflection became his hallmark. These works often carried a narrative element, inviting viewers to imagine the story behind the depicted scene.

Another significant work, often cited as representative of his mature style, is Public Opinion, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1863. This painting cleverly depicts a group of people gathered before a painting at an exhibition, presumably the Royal Academy itself, showcasing various reactions and discussions. It was lauded for its engaging subject matter and its commentary on the nature of art viewing and criticism, demonstrating O'Neill's ability to tackle slightly more complex social themes within his genre framework.

His subjects frequently included idyllic portrayals of English country life, reflecting a nostalgia for rural simplicity that was common during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Works depicting family meals, friendly visits, musical evenings, or children playing in sunlit gardens conveyed a sense of harmony and contentment that appealed greatly to middle-class patrons. These patrons, often industrialists and entrepreneurs, eagerly collected O'Neill's work.

Interestingly, O'Neill often used his own family members and friends as models for his paintings. His wife, Emma Callcott, whom he married in 1857, and their children likely feature in many of his domestic scenes. Anecdotally, it's suggested that he could be quite critical of his sitters' ability to hold a pose or convey the desired expression, highlighting the practical challenges behind his carefully constructed compositions.

The Cranbrook Colony: Community and Collaboration

George Bernard O'Neill was a central figure in the formation and flourishing of the Cranbrook Colony, an informal group of artists who settled in and around the village of Cranbrook in Kent from the mid-1850s onwards. This group shared a common interest in depicting rural life and genre scenes, often drawing inspiration directly from their surroundings and the local inhabitants.

The colony wasn't a formal institution but rather a close-knit community of like-minded artists who lived and worked in proximity, socialized together, and shared artistic ideals. Key members included Thomas Webster, who was something of a senior figure, Frederick Daniel Hardy, and Frederick's brother, George Hardy. John Callcott Horsley, another prominent Victorian painter and O'Neill's brother-in-law (Emma O'Neill's brother), was also closely associated with the group.

These artists often depicted similar subjects, focusing on detailed renderings of cottage interiors, village events, and the lives of ordinary people, though each maintained their individual style. They frequently used local villagers and each other's families as models. O'Neill himself purchased a picturesque, timber-framed house in Cranbrook, known as "Old Wilsley," which served as his home, studio, and a source of inspiration, featuring in several of his paintings. It also functioned as a summer retreat for the family.

The Cranbrook artists valued realism and narrative clarity, often imbuing their scenes with gentle humour or sentiment. Their work stood somewhat apart from the more dramatic or overtly moralizing trends seen in some other Victorian art, such as the works of Augustus Egg, or the detailed symbolism of the Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais or William Holman Hunt. Instead, the Cranbrook Colony focused on the charm and quiet dignity of everyday rural existence.

Collaboration and mutual support were characteristic of the group. O'Neill is known to have collaborated directly with George Hardy on at least one painting, The Surprise, showcasing their close working relationship. The shared environment and frequent interaction undoubtedly fostered a degree of stylistic coherence within the colony, while also allowing for individual artistic development. O'Neill's involvement with the Cranbrook Colony was a defining aspect of his career, providing both subject matter and a supportive artistic community for several decades.

Wider Artistic Connections and Social Engagement

Beyond the close circle of the Cranbrook Colony, George Bernard O'Neill was an active participant in the broader London art world. His regular exhibitions at the Royal Academy kept him connected to the mainstream art scene and its prominent figures. He maintained friendships and professional associations with various artists beyond the Cranbrook group.

One notable connection was with the American-born painter James McNeill Whistler. Although their artistic styles and philosophies differed significantly – Whistler championing 'Art for Art's Sake' against the narrative and sentimental tendencies often found in O'Neill's work – O'Neill offered Whistler moral support during his infamous libel lawsuit against the influential critic John Ruskin in 1878. This indicates O'Neill's standing within the artistic community and his willingness to support a fellow artist, even one with contrasting aesthetic views. His circle also included figures like George Henry Boughton, another painter known for his historical and genre scenes.

O'Neill was also involved in organizations aimed at promoting the arts. He was associated with the London Art Union, an organization designed to encourage public interest in the visual arts and support artists through a subscription and lottery system for acquiring artworks. Furthermore, sources suggest he played a role in establishing initiatives related to etching, possibly connected to the Society of Painter-Etchers founded in 1880, reflecting an interest in graphic arts alongside his painting practice.

His engagement extended into the social life of the Cranbrook community as well, where he reportedly joined local societies, including literary groups and even a golf club. This paints a picture of an artist who was not reclusive but actively integrated into both his professional network in London and his local community in Kent. His work, popular among the rising middle and industrial classes, placed him firmly within the context of mainstream Victorian art, alongside hugely successful contemporaries like William Powell Frith, known for his panoramic scenes of modern life such as Derby Day. O'Neill's art, while perhaps less grand in scale, offered a similarly detailed and engaging reflection of contemporary society, albeit focused on more intimate settings.

Later Life, Legacy, and Historical Evaluation

George Bernard O'Neill continued to paint actively into the later decades of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century. He maintained his home and studio in Cranbrook, using it as a base for his work and family life. However, as artistic tastes began to shift towards the end of the Victorian era, with the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Aestheticism, the popularity of detailed narrative genre painting, including O'Neill's, began to wane somewhat.

While he continued to exhibit, the frequency of his new works appears to have decreased in his later years. The art world was moving in new directions, and the style that had brought him success in the 1850s and 1860s was becoming less fashionable. Despite this, he remained a respected figure, representing a tradition of skilled craftsmanship and accessible subject matter.

George Bernard O'Neill passed away in London on September 23, 1917, at the venerable age of 89. He left behind a substantial body of work that documents, with charm and sensitivity, the domestic and rural life of Victorian England.

In terms of historical evaluation, O'Neill is primarily remembered as a leading member of the Cranbrook Colony and a skilled practitioner of Victorian genre painting. His work is valued by social historians as much as art historians for its detailed depiction of period customs, interiors, and clothing. Paintings like The Foundling and Public Opinion are recognized for their engagement with contemporary social issues and the art world itself.

Compared to revolutionary figures like Whistler or the Pre-Raphaelites, O'Neill is generally not seen as a major innovator in terms of artistic style or technique. His adherence to detailed realism and narrative clarity, influenced by earlier masters like the Dutch Golden Age painters and British predecessors such as Sir David Wilkie, places him firmly within the established traditions of his time. His strengths lay in his observational skills, his ability to compose engaging multi-figure scenes, and his capacity to evoke sentiment without excessive melodrama.

While perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by artists who pushed aesthetic boundaries more radically, George Bernard O'Neill's contribution remains significant. His paintings offer enduring appeal through their warmth, technical proficiency, and intimate portrayal of human relationships and everyday moments within a specific historical context. His work continues to be appreciated by collectors and museum visitors for its accessible charm and its valuable record of Victorian life.

Conclusion

George Bernard O'Neill carved a distinct niche for himself within the bustling art world of 19th-century Britain. From his Irish roots and London training to his central role in the Cranbrook Colony, he developed a successful career based on finely wrought genre scenes that captured the hearts of the Victorian public. Influenced by Dutch Masters yet distinctly of his own time, he chronicled the quiet dramas and simple pleasures of domestic and rural life with sensitivity and skill. While artistic fashions changed throughout his long career, his work endures as a testament to his talent and as a rich visual resource for understanding the social fabric of the era he depicted so affectionately. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a keen observer of the human condition within the everyday settings of Victorian England.