George Goodwin Kilburne stands as a significant figure in the landscape of British Victorian art. Active during a period of immense social change, industrial growth, and evolving artistic tastes, Kilburne carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter primarily celebrated for his elegant and meticulously detailed depictions of English upper-middle-class life. Born on July 24, 1839, and living a long and productive life until his passing in 1924, Kilburne witnessed the zenith and the gradual fading of the Victorian era, capturing its sensibilities, fashions, and domestic interiors with a refined and observant eye. He was particularly adept in the medium of watercolour, though also proficient in oils, and his work continues to charm collectors and enthusiasts with its nostalgic glimpse into a bygone world of gentility and decorum.

The Formative Years: From Norfolk Roots to London Apprenticeship

George Goodwin Kilburne's journey into the art world began not in the bustling studios of London, but in the quieter setting of Hackford, near Reepham in Norfolk. He was the eldest son of Goodwin Kilburne, whose own background might have influenced the young George, though details remain sparse. His early education took place in Hawkhurst, Kent, suggesting a family move or a specific educational choice aimed at providing a solid foundation. However, the pivotal moment in his artistic formation occurred when, at the tender age of fifteen, he relocated to London to embark on a demanding five-year apprenticeship.

His destination was the workshop of the renowned Dalziel Brothers, engravers based in London. George Dalziel and Edward Dalziel were pre-eminent figures in the world of wood engraving, a crucial medium for illustration in the burgeoning print culture of the 19th century. Their firm produced countless illustrations for books and popular periodicals like Punch and The Illustrated London News. This apprenticeship was far from a casual arrangement; it was an intensive training in precision, draughtsmanship, and the translation of tone and texture into line for printing. The skills honed under the Dalziels – meticulous attention to detail, a steady hand, and a strong compositional sense – would prove invaluable throughout Kilburne's subsequent career as a painter. His employers reportedly held him in high esteem, recognizing his diligence and talent early on.

From Engraving to Easel: A Shift in Focus

Upon completing his rigorous apprenticeship around 1860, Kilburne initially continued to work in the field of engraving. This practical experience provided him with a livelihood and further refined his technical abilities. However, the constraints of working primarily in black and white, often interpreting the designs of others, may have eventually spurred a desire for greater artistic autonomy and the expressive possibilities of colour. By the early 1860s, Kilburne made the decisive shift towards painting, dedicating himself increasingly to watercolour and, to a lesser extent, oil painting.

This transition was not necessarily an abrupt break but likely a gradual evolution. His engraver's eye for detail remained a hallmark of his painted work. He didn't pursue the grand historical or mythological subjects favoured by some Royal Academicians, nor the stark social realism emerging in other quarters. Instead, he found his métier in genre painting – scenes of everyday life, albeit a specific, comfortable stratum of it. His training ensured a high degree of finish and accuracy, qualities highly valued by the Victorian art market.

Defining the Kilburne Style: Elegance and Detail

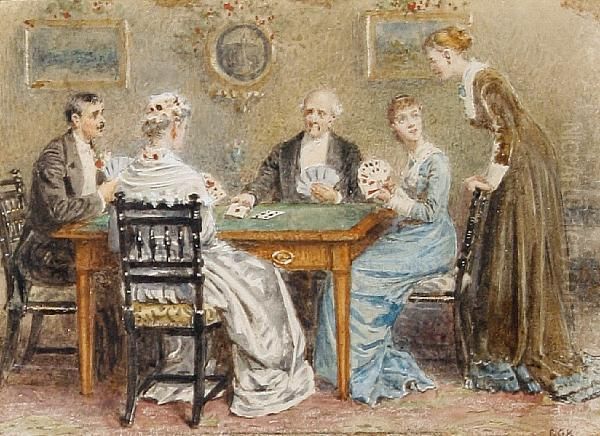

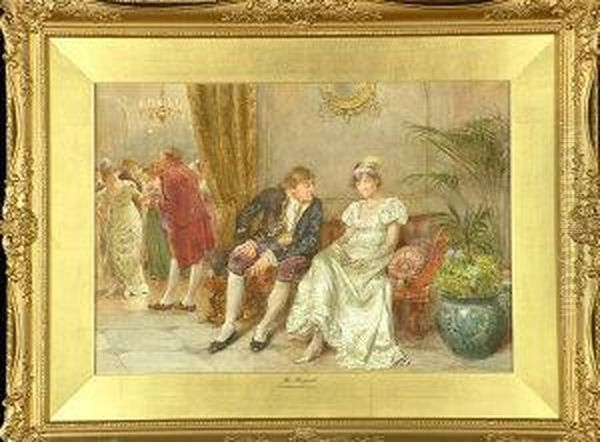

George Goodwin Kilburne's artistic signature is one of refined elegance and meticulous observation. His paintings typically depict the leisured activities and domestic interiors of the affluent upper-middle and gentry classes of Victorian and Edwardian England. Drawing rooms, conservatories, gardens, and libraries form the backdrops for his charming vignettes. Within these settings, he portrays well-dressed men, women, and children engaged in polite social interactions: taking tea, reading letters, playing music, engaging in quiet conversation, or enjoying garden strolls.

His figures are invariably graceful and poised, clad in the fashionable attire of the day, rendered with an almost photographic attention to the textures of silk, lace, and tweed. Furniture, drapery, porcelain, and floral arrangements are depicted with equal care, contributing to an overall impression of comfortable prosperity and cultivated taste. Kilburne's colour palette is generally bright and pleasing, favouring clear tones and avoiding dramatic chiaroscuro. The mood is typically serene, untroubled, and gently sentimental, reflecting the era's preference for reassuring and aesthetically pleasing narratives. He captured the nuances of social etiquette and the quiet rhythms of domestic life within a specific social milieu.

Watercolour: A Favoured Medium

While Kilburne worked competently in oils, watercolour was arguably the medium in which he truly excelled and gained his widest recognition. The transparency and luminosity of watercolour lent themselves perfectly to his delicate style and detailed approach. He possessed a remarkable ability to control the medium, achieving fine detail and subtle gradations of tone without sacrificing freshness. His handling of light, particularly in interior scenes where sunlight streams through windows, is often a notable feature, adding warmth and atmosphere to his compositions.

His mastery was formally acknowledged early in his painting career. In 1866, he was elected an Associate of the prestigious Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour (RI), achieving full membership just two years later, in 1868. This affiliation placed him firmly within the mainstream of the British watercolour tradition, a lineage stretching back to artists like Paul Sandby and Thomas Girtin, and flourishing in the 19th century with masters such as J.M.W. Turner and later figures like Myles Birket Foster, whose charming rural scenes shared some affinity with Kilburne's focus on idyllic life, albeit in different settings. Kilburne remained a regular and prominent exhibitor at the RI throughout his long career.

Ventures in Oil and Genre Scenes

Kilburne's work in oil painting often mirrored the subjects and style of his watercolours, though the medium allowed for richer colours and textures, and sometimes a slightly larger scale. He became a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI) in 1883, further cementing his status within the established art institutions of London. His oil paintings often depict similar interior scenes, conversations, and moments of quiet domesticity.

He demonstrated versatility, however, tackling different types of genre subjects. His skill in depicting figures and fabrics remained paramount, whether the scene was an intimate family gathering or a more populated social event. These works appealed strongly to Victorian tastes for narrative and relatable human situations, presented within an aspirational context of comfort and social grace. Unlike some contemporaries such as William Powell Frith, known for sprawling, detailed canvases of modern life like Derby Day, Kilburne generally preferred more intimate and less crowded compositions, focusing on smaller groups or individuals within elegantly appointed spaces.

Capturing the Hunt: A Sporting Interest

Beyond the drawing-room and garden party, Kilburne also displayed a keen interest in depicting sporting scenes, particularly fox hunting. This likely stemmed from a personal interest in country pursuits, common among the gentry class he often portrayed. His hunting scenes capture the colour, energy, and traditions of the chase, featuring riders in their distinctive red coats, hounds in full cry, and the landscapes of the English countryside.

Notable examples include the oil painting Full Cry (1898), which vividly portrays the hounds closing in on their quarry, showcasing his ability to render animals in motion. A watercolour Hunting Scene Triptych from 1900 further demonstrates his engagement with this theme. Another work, titled Fox Hunting, The Chase, Yorkshire: 1895, pinpoints a specific regional context for his sporting art. These works add another dimension to his oeuvre, showing his capacity to handle more dynamic outdoor subjects alongside his more characteristic tranquil interiors.

Signature Works and Enduring Themes

Several specific works are frequently cited as representative of Kilburne's output. The Music Room encapsulates his skill in rendering elegant interiors populated by graceful figures engaged in cultured leisure. A Game of Cards likely depicts a quiet moment of domestic entertainment, allowing for the portrayal of focused expressions and detailed costume. A Festive Offering suggests a scene related to gift-giving or celebration, perhaps Christmas or a birthday, themes popular in Victorian genre painting.

The New Arrival probably portrays the introduction of a new member to a household or social circle – perhaps a baby, a pet, or a visitor – allowing for gentle narrative and emotional interplay. The intriguingly titled Casabianca (described in one source as a grisaille watercolour) might reference the famous poem by Felicia Hemans about a boy standing on a burning ship, but given Kilburne's usual subject matter, it's more likely a genre scene perhaps playfully alluding to the theme of steadfastness or duty in a domestic context, or simply a title chosen for its familiarity. Across these works, the recurring themes are social interaction, domestic comfort, leisure, and the quiet dramas of everyday life among the well-to-do, all rendered with his characteristic polish and charm.

Navigating the Victorian Art World: Exhibitions and Affiliations

Success in the competitive London art world of the 19th century depended heavily on exhibiting work regularly and gaining recognition from established institutions. Kilburne proved adept at navigating this system. His long association with the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour (RI) and the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI) provided prestigious platforms for showcasing his art. He also exhibited frequently at the Royal Academy of Arts, the pinnacle of the British art establishment, showing some 29 works there between 1863 and 1918.

Furthermore, his work was seen at other significant venues across Britain, including the Royal Society of British Artists (Suffolk Street), the Grosvenor Gallery (a more progressive alternative to the RA for a time), the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, Manchester Art Gallery, and the Royal Society of Artists in Birmingham (where he exhibited 18 works). This widespread exposure ensured his name and style became familiar to a broad audience of potential patrons and critics. His membership in the Royal Miniature Society (RMS) from 1898 indicates his skill extended to smaller, highly detailed formats as well. The reproduction of his paintings as prints, sometimes appearing in illustrated journals like The Graphic, further disseminated his images and contributed to his popularity.

Kilburne in Context: Peers and Movements

To fully appreciate Kilburne's place, it's helpful to consider him alongside his contemporaries and the broader artistic currents of the time. His direct mentors were the engravers George Dalziel and Edward Dalziel. His focus on charming watercolour scenes aligns him with artists like Myles Birket Foster and Helen Allingham, though their subjects often leaned more towards rural cottages and landscapes.

In the realm of oil genre painting depicting upper-class life, the French artist James Tissot, who worked in London for a decade, explored similar territory but often with a sharper, more fashionable, and sometimes subtly ambiguous edge. William Powell Frith captured larger social panoramas, while Marcus Stone specialized in sentimental historical genre scenes, often with a focus on courtship.

Kilburne's polished, detailed style contrasts sharply with the aims of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (e.g., John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt), who sought intense detail but combined it with moral seriousness, symbolism, and often medieval or literary themes. It also differs from the Aesthetic Movement, championed by artists like James McNeill Whistler and Albert Moore, who prioritized formal harmony and beauty ("Art for Art's Sake") over narrative content.

Furthermore, his comfortable depictions stand apart from the Social Realism of painters like Luke Fildes or Hubert von Herkomer, who tackled subjects of poverty and hardship. While later portraitists like John Singer Sargent also depicted the upper classes, Sargent's bravura brushwork and psychological insight represent a different, more modern sensibility compared to Kilburne's meticulous Victorian finish. Kilburne operated successfully within a popular, established tradition, fulfilling a demand for well-crafted, pleasing images of contemporary elite life. He shared exhibition spaces with artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema, known for his classical scenes, and Briton Rivière, famed for his animal paintings, reflecting the diverse tastes catered to by institutions like the Royal Academy.

A Private Life: Family and Later Years

In 1862, George Goodwin Kilburne married Janet Dalziel, the niece of his former employers, the Dalziel brothers. This union further cemented his ties to the influential Dalziel circle and likely facilitated his integration into London's artistic and social scenes. The couple had children, including a son, George Goodwin Kilburne Jr. (1863-1938), who also became an artist, specializing in animal and sporting subjects, and a daughter, Florence (born c. 1865).

For many years, the family resided in Hampstead, a North London suburb popular with artists and writers. Kilburne maintained a studio at Steeles Studios, Haverstock Hill, for a significant part of his career. While his professional life was marked by steady success, later biographical accounts sometimes hint at complexities in his personal life, including a close relationship with his granddaughter in his later years after his wife's passing. Reliable details on these aspects remain somewhat limited.

A significant hardship Kilburne faced in his old age was failing eyesight, a cruel affliction for a painter whose style depended so heavily on precision and detail. This condition likely curtailed his artistic output in his final years. His wife Janet predeceased him, passing away in 1916. George Goodwin Kilburne himself died in London on June 13, 1924, at the venerable age of 85, having lived through the entirety of the Edwardian era and into the post-World War I period.

Enduring Appeal and Legacy

George Goodwin Kilburne's legacy rests on his considerable skill as a draughtsman and watercolourist, and his role as a charming chronicler of a specific segment of Victorian and Edwardian society. He was not a radical innovator who challenged artistic conventions; rather, he was a master craftsman who perfected a particular type of genre painting that found immense favour with the public and patrons of his time. His work provides valuable visual documentation of the costumes, interiors, and social customs of the English upper classes during his long career.

His paintings, particularly the watercolours, remain popular in the art market today. They evoke a sense of nostalgia for an era often perceived, rightly or wrongly, as one of greater elegance, stability, and decorum. While perhaps lacking the emotional depth or social commentary found in the work of some of his contemporaries, Kilburne's art possesses an undeniable aesthetic appeal, technical proficiency, and historical interest. His works are held in numerous public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Manchester Art Gallery, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, and various regional galleries throughout the UK, ensuring his contribution to British art history is preserved and accessible.

Conclusion: Chronicler of Elegance

George Goodwin Kilburne navigated the bustling art world of Victorian London with skill and dedication, establishing himself as a leading painter of genre scenes, particularly in watercolour. His meticulous attention to detail, refined compositions, and focus on the elegant lifestyles of the upper classes resonated deeply with the tastes of his era. While artistic fashions have changed, his work endures as a beautifully rendered window onto the world of Victorian gentility, admired for its technical mastery and its power to evoke the atmosphere of a bygone age. He remains a significant figure for understanding the popular aesthetics and social aspirations reflected in the art of his time.