Introduction: A Painter of Childhood and Community

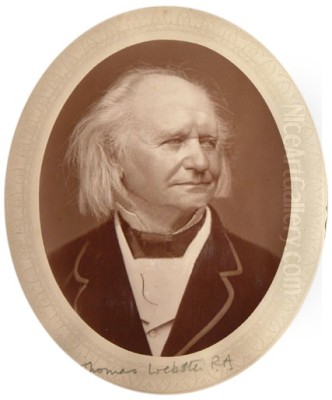

Thomas Webster RA (Royal Academician) stands as a significant figure in 19th-century British art, celebrated for his charming and often humorous depictions of rural life, particularly focusing on the world of children. Born at the dawn of the century, his long life (1800-1886) spanned a period of immense social and artistic change in Britain. Webster carved a distinct niche for himself, creating genre scenes filled with anecdote, warmth, and meticulous detail that resonated deeply with the Victorian public. His paintings, often set in schoolrooms, village playgrounds, or cottage interiors, captured the joys, mischief, and simple dramas of everyday existence, making him one of the most popular artists of his time. He was a key member of the Royal Academy and a central figure in the later formation of the Cranbrook Colony, further cementing his place in the narrative of British art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Thomas Webster was born in Pimlico, London, on March 10, 1800. His father held a position in the household of King George III and later George IV, providing a connection, albeit modest, to the circles of the establishment. Initially, young Thomas seemed destined for a career in music. Possessing a fine voice, he became a chorister, first at St George's Chapel in Windsor Castle and later at the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace, London. This early exposure to music and performance perhaps subtly influenced the sense of rhythm and composition found in his later paintings.

However, a growing passion for visual art eventually led him to change course. Around the age of 20 or 21, Webster decided to pursue painting seriously. He gained admission to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1821, demonstrating sufficient talent to embark on formal training. This was a crucial step, placing him within the institutional heart of the British art world, where he would learn alongside other aspiring artists and under the tutelage of established Academicians. His dedication and skill were soon recognized.

Webster's time at the Royal Academy Schools proved fruitful. He applied himself diligently to his studies, mastering the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and painting. His progress culminated in 1824 when he won the first medal in the school of painting, a significant honour that marked him as a student of exceptional promise. This early success likely bolstered his confidence and set the stage for his professional career. His training grounded him in the academic traditions of the time, emphasizing careful draughtsmanship and structured composition, elements that would remain characteristic of his work throughout his life.

Establishing a Reputation: The Royal Academy Years

Following his success at the RA Schools, Webster began exhibiting his work regularly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions, the most important venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage in Britain. His chosen specialty was genre painting – scenes of everyday life – with a particular emphasis on children. An early work that garnered significant attention was Rebels Shooting a Prisoner (exhibited RA 1825), later known as The Prisoner. This painting, depicting a group of boys playfully aiming toy guns at a doll propped against a wall, captured a sense of childhood mimicry and play that proved highly popular. Its success indicated Webster's knack for identifying themes that appealed to public sentiment.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Webster solidified his reputation with a series of works that explored the world of the village school, playground antics, and domestic scenes. He developed a distinct style characterized by clear storytelling, careful observation of human expression and gesture, and a gentle, often humorous, tone. His paintings were accessible, relatable, and imbued with a nostalgic charm that resonated with a Victorian audience increasingly looking back to idealized visions of rural simplicity amidst rapid industrialization.

His growing success led to official recognition from the Royal Academy. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1840, a significant step up in the art establishment hierarchy. This was followed by his election as a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1846, placing him among the elite of British artists. Membership in the RA brought prestige, exhibition privileges, and a role in the governance of the institution, confirming his status as a leading painter of his generation. He exhibited alongside contemporaries like the animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, the great landscape artists J.M.W. Turner and John Constable (though their styles differed greatly), and fellow genre painters who were rising in prominence.

Masterpieces of Childhood and Village Life

During his peak years exhibiting at the Royal Academy, Webster produced many of his most famous and beloved works. The Smile and The Frown (exhibited RA 1841) were a pair of paintings contrasting the reactions of schoolchildren, showcasing his ability to capture subtle expressions and create engaging narratives within a familiar setting. The Boy with Many Friends (exhibited RA 1841) explored themes of popularity and social dynamics among children, again demonstrating his observational skills.

Perhaps his most iconic work from this period is Punch (exhibited RA 1840). This lively painting depicts a crowd of villagers, young and old, gathered around a travelling Punch and Judy show. It is a masterful composition, filled with varied characters and reactions, capturing the energy and communal enjoyment of a popular entertainment. The painting exemplifies Webster's skill in orchestrating complex group scenes and infusing them with humour and vitality. It was incredibly popular and widely reproduced as an engraving, significantly broadening Webster's fame.

Another highly celebrated work is The Football Game (1839, though exhibited later). This painting vividly portrays the rough-and-tumble energy of a village football match, a far cry from the codified sport of today. Boys swarm across a field, chasing the ball with chaotic enthusiasm, while villagers watch from the sidelines. It captures a sense of boisterous, unrestrained rural activity and community spirit. Like Punch, it presents an idealized yet dynamic vision of traditional English life that held great appeal.

Sickness and Health (exhibited RA 1843) showed a more sentimental side, contrasting a robust, healthy child with one who is pale and convalescing, attended by its mother. This work tapped into Victorian sensibilities regarding childhood fragility, family bonds, and the precariousness of health – reflecting, as noted in the initial information, societal concerns such as high child mortality rates. It demonstrated Webster's ability to evoke pathos as well as humour. A Dame's School (exhibited RA 1845) returned to the familiar schoolroom setting, depicting young children under the watchful eye of an elderly schoolmistress, capturing the quiet industry and occasional mischief of early education.

The Cranbrook Colony: A Rural Artistic Haven

In 1856, seeking a quieter life and perhaps closer proximity to the rural subjects he loved to paint, Thomas Webster moved from London to the picturesque village of Cranbrook in the Weald of Kent. This move marked a significant new chapter in his life and career. Cranbrook, with its charming old buildings and surrounding countryside, provided ample inspiration for his work. He was not alone in recognizing its appeal.

Soon after Webster settled there, other artists began to follow, attracted by the village's rustic charm and perhaps by Webster's presence as a respected senior figure. This informal gathering of artists became known as the Cranbrook Colony. Key members included Frederick Daniel Hardy, his brother George Hardy, John Callcott Horsley (who was related by marriage to the engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and was known for designing the first Christmas card), George Bernard O'Neill, and later Augustus Edwin Mulready (nephew of the famous genre painter William Mulready).

The Cranbrook Colony artists shared a common interest in depicting scenes of everyday rural and domestic life, often using local villagers and their own families as models. They worked in a style characterized by detailed realism, careful finish, and narrative content, often with a nostalgic or sentimental flavour. There was a clear influence from 17th-century Dutch and Flemish genre painters like Jan Steen and David Teniers the Younger, admired for their depictions of peasant life, domestic interiors, and meticulous technique. Webster, as the established RA, naturally became the elder statesman of the group.

Living and working in close proximity, the artists influenced each other, sometimes sharing props, models, and studio spaces. They often depicted similar subjects – cottage interiors, village events, children at play – yet each maintained their individual style. Webster continued to produce works that were exhibited at the Royal Academy, drawing inspiration from his new surroundings. His presence helped lend credibility and visibility to the Colony as a distinct, albeit informal, artistic group within the broader landscape of Victorian art.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

Thomas Webster's artistic style remained relatively consistent throughout his long career, characterized by meticulous attention to detail, strong narrative clarity, and a warm, engaging tone. He was a superb draughtsman, grounding his compositions in careful drawing and observation. His figures are well-rendered, with expressive faces and gestures that clearly convey the story or emotion of the scene. He typically employed a warm colour palette and smooth brushwork, aiming for a high degree of finish that appealed to Victorian tastes for realism.

His primary influence, particularly evident in the Cranbrook years, was 17th-century Dutch and Flemish genre painting. Artists like Jan Steen, Adriaen van Ostade, and David Teniers the Younger provided models for depicting everyday life with realism, detail, and often humour or moral undertones. Webster adapted this tradition to a specifically English, Victorian context, focusing on the perceived virtues of rural simplicity, family life, and community. He shared this affinity for Dutch models with earlier British genre painters like Sir David Wilkie, whose work had paved the way for the popularity of such scenes in the early 19th century.

Another significant influence, especially on his depictions of children, was William Mulready RA (1786-1863). Mulready was a highly respected elder contemporary known for his finely drawn and composed genre scenes, often featuring children. Webster clearly admired Mulready's work, and there are parallels in their subject matter and careful technique, although Webster's paintings often possess a slightly broader humour compared to Mulready's more restrained classicism.

Thematically, Webster consistently returned to the world of childhood. He depicted children learning in dame schools, playing games like football or marbles, engaging in mischief, experiencing minor triumphs and disappointments. These scenes were imbued with a sense of innocence and nostalgia, reflecting a common Victorian idealization of childhood. He also frequently painted scenes of village life: gatherings, festivities like Punch, musical moments like A Village Choir, and quiet domestic interiors. His work celebrated community, simple pleasures, and traditional values, offering a comforting counterpoint to the complexities and anxieties of modernizing Britain. While often humorous, his work occasionally touched on more serious themes like sickness or poverty, but generally maintained a positive and reassuring outlook. His style stood in contrast to the more radical artistic developments of his time, such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, who sought a different kind of realism and intensity, often drawing on literary or religious themes.

Focus on Key Works: A Village Choir and Others

While The Football Game and Punch represent Webster's dynamic depictions of village activity, A Village Choir (dated 1847, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London) showcases his skill in capturing character and gentle humour within a more contained setting. The painting depicts a group of rustic musicians and singers gathered in the gallery of a village church, earnestly performing during a service. Each figure is a distinct character study, from the absorbed cellist to the various singers, some concentrating intently, others perhaps slightly off-key or distracted.

The humour in A Village Choir is gentle and affectionate, derived from the careful observation of human quirks and the charming lack of polished professionalism among the performers. It celebrates the sincerity and community spirit of village traditions. The composition is carefully arranged, leading the viewer's eye across the different figures, and the details of clothing, instruments, and the church setting are rendered with Webster's characteristic precision. Acquired for the national collection by the V&A, it remains one of his most well-known and appreciated works, embodying his talent for capturing the essence of rural English life.

Webster's success was significantly amplified by the widespread reproduction of his paintings as engravings. Prints after works like Punch, The Smile, The Frown, and A Village Choir were immensely popular, bringing his images into middle-class homes across Britain and the Empire. This dissemination through print media was crucial to his fame and financial success, making his vision of childhood and village life a familiar part of Victorian visual culture. Artists like William Powell Frith, another master of the crowded Victorian narrative scene (e.g., Derby Day, The Railway Station), also benefited greatly from the market for engravings, highlighting the importance of reproductive prints during this era.

Later Life, Retirement, and Legacy

Thomas Webster continued to live and work in Cranbrook for the remainder of his life, remaining an active painter well into his later years. He maintained his connection with the Royal Academy, exhibiting there regularly until his retirement. In 1876, at the age of 76, he retired from the Royal Academy, taking the status of Honorary Retired Academician. This marked the formal end of his active participation in the institution he had been associated with for over fifty years.

He spent his final decade peacefully in Cranbrook, surrounded by the village scenery he loved and the community of artists he had helped foster. He died there on September 23, 1886, at the venerable age of 86. His long life had witnessed the entirety of the Victorian era, and his art had perfectly captured many aspects of its social fabric and sentiment.

During his lifetime, Webster enjoyed enormous popularity. His paintings commanded high prices, and the demand for engravings after his work was substantial. He was seen as a wholesome, charming painter whose work celebrated the best of English character and tradition. However, towards the end of his life and particularly after his death, artistic tastes began to change. The detailed narrative realism of Victorian genre painting fell out of critical favour, overshadowed by the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and other modern art movements emerging from France and elsewhere. Figures like James McNeill Whistler, with his emphasis on "art for art's sake," represented a stark contrast to Webster's anecdotal approach.

Consequently, Webster's reputation, along with that of many other Victorian genre painters, declined significantly in the early 20th century. His work was often dismissed as overly sentimental or anecdotal. However, from the mid-20th century onwards, there has been a gradual reassessment of Victorian art. Art historians began to appreciate the technical skill, social observation, and cultural significance of painters like Webster and the Cranbrook Colony. His work is now recognized for its value as a record of 19th-century life, its technical accomplishment, and its genuine charm and warmth. Museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Britain, and various regional galleries proudly display his works.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Victorian England

Thomas Webster RA occupies a secure place in the history of British art as one of the foremost genre painters of the Victorian era. His specialization in scenes of childhood and village life, rendered with meticulous detail, gentle humour, and narrative clarity, struck a powerful chord with his contemporaries. From his early successes at the Royal Academy Schools to his long and productive career as a full Academician and his later role as the patriarch of the Cranbrook Colony, Webster consistently created images that celebrated community, innocence, and the simple pleasures of everyday existence.

While his style was rooted in the academic traditions of his training and influenced by the Dutch Golden Age masters like Steen and Teniers, and fellow British artists like Wilkie and Mulready, Webster developed a distinctive voice. His paintings, such as The Football Game, Punch, and A Village Choir, remain engaging and informative windows into the social world of 19th-century England. Though his critical fortunes waned with the advent of modernism, his work has rightly earned renewed appreciation for its artistic merit and its value as a charming and insightful chronicle of Victorian life. He remains a testament to the enduring appeal of art that finds significance and delight in the ordinary.