Introduction: An Artist Between Worlds

George Chinnery stands as a unique figure in the annals of British art history, an accomplished painter whose life and career unfolded far from the artistic centers of London. Born in 1774 and dying in Macau in 1852, Chinnery spent the majority of his working life in India and China. He became renowned for his insightful portraits, vibrant landscapes, and intimate genre scenes that captured the essence of life in the East during a period of burgeoning global interaction. His work serves not only as a testament to his considerable artistic skill but also as an invaluable historical record of the societies, individuals, and environments he encountered. Chinnery acted as a crucial conduit for artistic exchange, particularly notable for being the most significant Western painter to reside long-term on the China Coast in the early nineteenth century, profoundly influencing local artists.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in London

George Chinnery was born in London in January 1774. He was the son of William Chinnery, a writing master and owner of a prestigious academy, known for his skills in calligraphy and connections to the East India Company. Another William Chinnery, George's elder brother, would also pursue painting, though his path diverged significantly. Growing up in an environment that valued draftsmanship likely nurtured George's innate artistic talents. He demonstrated promise early on, and by the age of 17, in 1791, he began exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

The Royal Academy, under the formidable presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds during Chinnery's formative years, was the epicenter of the British art world. Studying there, even if briefly or informally through its schools and exhibitions, exposed Chinnery to the prevailing standards of portraiture and history painting. He quickly established himself as a capable miniaturist and portrait painter in London, absorbing the stylistic influences of leading figures, though his early career was marked by a restlessness that would define his life.

The Dublin Years: Establishing a Reputation

Around 1796 or shortly thereafter, Chinnery moved to Dublin, Ireland. This move coincided with a period of political turmoil, culminating in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, although the provided text confusingly mentions a move in 1802 due to the rebellion. While in Dublin, he married Marianne Vigne in 1799, the daughter of a local jeweler. The couple would have two children. Dublin offered a thriving, albeit smaller, art market compared to London. Chinnery quickly gained recognition as a talented portraitist, exhibiting regularly with the Society of Artists in Ireland.

His time in Dublin allowed him to hone his skills, particularly in oil portraiture, moving beyond miniatures. He captured the likenesses of various members of Irish society. His style during this period reflected the fashionable elegance of contemporary British portraiture, perhaps aspiring to the success of artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was becoming the dominant force in London. However, Chinnery's financial affairs began to show signs of strain, a recurring theme throughout his life, possibly exacerbated by his growing family and perhaps a penchant for living beyond his means.

Passage to India: The Madras Chapter

By 1802, facing mounting debts and perhaps seeking new opportunities, Chinnery made the momentous decision to leave his family and sail for India. He arrived in Madras (modern-day Chennai), a major center of the British East India Company's operations. The provided text notes he lived there for five years. India, at this time, offered lucrative prospects for European artists willing to cater to the demand for portraits from Company officials, military officers, merchants, and local rulers eager to emulate European tastes.

In Madras, Chinnery continued to work primarily as a portrait painter, documenting the faces of the Anglo-Indian community and occasionally Indian dignitaries. He joined a lineage of British artists who had sought fortune in India, such as Tilly Kettle and Johan Zoffany, who had worked there in the preceding decades. Chinnery's Madras period saw him further develop his technique, capturing not just likenesses but also the character and status of his sitters within the colonial hierarchy. He also began sketching the local environment – landscapes, architecture, and scenes of daily life – a practice that would become central to his later work.

Flourishing in Calcutta

Around 1807, Chinnery relocated from Madras to Calcutta (modern-day Kolkata), then the capital of British India and a significantly larger, wealthier, and more cosmopolitan city. The provided text mentions he left Ireland in 1807 due to financial difficulties and went to India, which seems chronologically inconsistent with his arrival in Madras in 1802; it's more likely he left Ireland for Madras in 1802, and moved within India from Madras to Calcutta around 1807. Calcutta represented the zenith of his Indian career. He became the leading European artist in the city, highly sought after for his portraits.

His studio was a hub of activity, and he painted governors-general, judges, merchants, and their families. His style matured, characterized by confident brushwork, rich color, and an ability to convey personality. Beyond formal portraits, he produced numerous sketches and watercolors of Calcutta's bustling streets, its grand colonial architecture, the Hooghly River, and the surrounding countryside. These works show his keen eye for detail and his growing fascination with the local Indian population and their way of life, often depicted with sensitivity and dynamism. Artists like Thomas Daniell and his nephew William Daniell had previously documented India's landscapes and monuments, but Chinnery focused more on the human element and the immediacy of the scene. Despite his success, financial troubles continued to plague him.

Escape to Macau: The Final Chapter on the China Coast

By 1825, Chinnery's debts in Calcutta had become overwhelming. Facing the prospect of creditors closing in, he once again chose flight over confrontation. He secretly boarded a ship bound for the China Coast, eventually settling in the Portuguese enclave of Macau. He would remain there, with frequent visits to nearby Canton (Guangzhou), for the final 27 years of his life. At that time, Macau and the limited area around the Canton factories were the only places in China where foreign trade and residence were permitted under the strict regulations of the Qing Dynasty's Canton System.

Chinnery's arrival in Macau marked the beginning of the most distinctive phase of his career. He became the only resident Western professional artist of significance on the China Coast during this period. While artists like William Alexander had accompanied diplomatic missions and Thomas Allom created views based on sketches by others, Chinnery lived and worked amongst the community he depicted. This unique position allowed him unparalleled access to the life of the Pearl River Delta, a melting pot of cultures – Portuguese, British, American, Chinese, and others involved in the lucrative China Trade.

Documenting the Pearl River Delta: Art in Macau and Canton

In Macau and Canton, Chinnery continued to paint portraits, primarily of the Western merchants, sea captains, and officials involved in the trade, as well as prominent Chinese merchants, known as Hong merchants, such as the famous Howqua (Wu Bingjian), whom he painted multiple times. These portraits are valuable records of the key figures navigating the complex world of Sino-Western commerce before the Opium Wars. However, it is perhaps his landscapes and genre scenes that are most celebrated from this period.

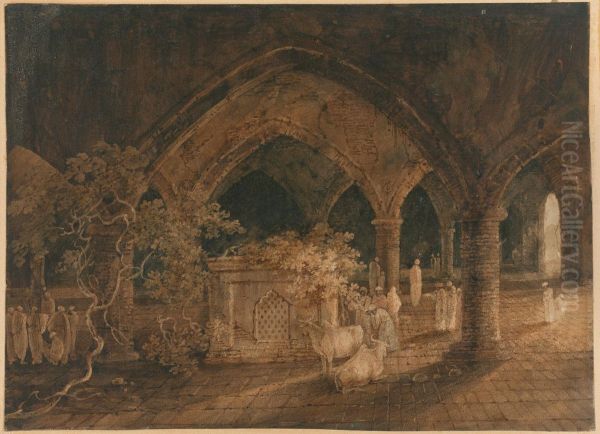

He tirelessly sketched the narrow, winding streets of Macau, its baroque churches, bustling harbors, and tranquil gardens. He depicted the boat people (Tanka) living on the Pearl River, street vendors, blacksmiths, gamblers, and artisans going about their daily lives. His sketches, often annotated in his personal shorthand based on the Gurney system, formed the basis for more finished watercolors and oil paintings. These works are characterized by their immediacy, capturing light, atmosphere, and human activity with remarkable vivacity. They provide an intimate and invaluable visual record of the region's culture and appearance in the decades before photography became widespread and before conflict irrevocably changed the landscape.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Chinnery was a versatile artist, proficient in multiple media. His oil paintings, particularly his portraits, show the influence of British academic tradition, with strong modeling, attention to texture, and often dramatic lighting reminiscent of contemporaries like Lawrence, though adapted to his Eastern subjects. He excelled in capturing the individuality of his sitters.

His watercolors are noted for their freshness and luminosity, skillfully blending transparent washes with opaque highlights. He often combined watercolor with pen and ink outlines, giving structure and definition to his compositions. Perhaps most prolific were his drawings in pencil and ink. He carried sketchbooks everywhere, constantly observing and recording. His use of shorthand annotations on these sketches is a unique feature, allowing him insights into his working process and sometimes identifying subjects or locations. This dedication to sketching from life imbued his finished works with authenticity and energy. His style effectively merged the "softness of watercolor with the brilliance of oil painting," capturing the unique light and atmosphere of Southern China.

Teaching and Influence: The Chinnery School

Beyond his own artistic output, Chinnery played a crucial role as a teacher and mentor in Macau. He was effectively the first Western artist to systematically teach Western painting techniques, particularly oil painting based on the British academic model, to Chinese artists. His most famous pupil was Lam Qua (Guan Qiaochang), who likely worked in Chinnery's studio before establishing his own highly successful workshop in Canton.

Lam Qua and other artists influenced by Chinnery adopted his realistic style, particularly for portraits commissioned by Western clients, contributing significantly to the development of Chinese export painting. This interaction created a distinct "Chinnery School" or style that blended Western naturalism with local subjects and perspectives. This artistic exchange represents a significant moment in Sino-Western cultural relations, predating the more formal art academies established later in the century. Chinnery also interacted with other visiting Western artists, such as the French painter Auguste Borget, who spent time in Macau, and mentored younger figures like the British-Indian amateur artist William Prinsep during Prinsep's visit.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Chinnery's World

Chinnery's oeuvre is extensive. Among his key works are:

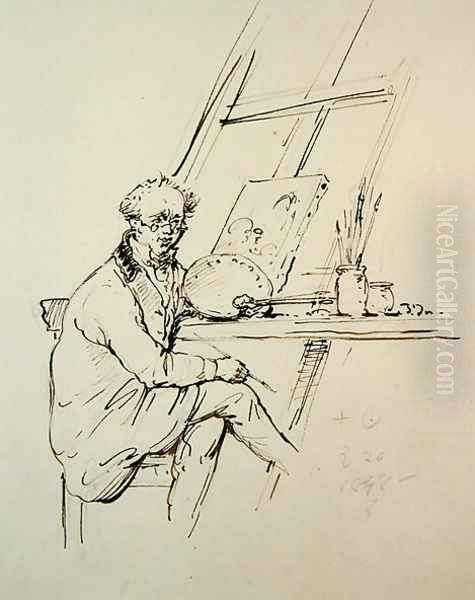

Self-Portraits: Chinnery painted numerous self-portraits throughout his career, offering insights into his appearance and perhaps his state of mind. A notable late example from around 1840 shows him as an aging but still observant artist.

Portraits of Merchants: His portraits of Western merchants and Chinese Hong merchants like Howqua are iconic representations of the Canton trade era. The Portrait of Howqua (several versions exist) captures the dignity and intelligence of one of the wealthiest men in the world at the time.

Scenes of Daily Life: Countless sketches, watercolors, and oils depict street scenes in Macau and Canton, such as A Blacksmith's Shop, Gamblers in a Street, and views of the Praya Grande in Macau. These are invaluable for their social and historical detail.

Indian Subjects: Works from his Indian period include portraits of colonial officials and landscapes like An Indian Tomb (RISD Museum) or Thatched Building in a Wood (Yale Center for British Art, 1814), showcasing his interest in local architecture and scenery.

Dr. Robert Morrison and his Chinese Assistants: This group portrait depicts the pioneering Protestant missionary and translator Robert Morrison, likely working on his Chinese dictionary or Bible translation. The work has been interpreted in various ways, some seeing it as a straightforward depiction, others suggesting subtle commentary on the colonial encounter. The initial confusion in the provided text mentioning Saint Milton Translating the Bible likely refers to this significant work featuring Morrison.

Mouqua (1828): Described as depicting a Chinese woman seated on a redwood bench, this work exemplifies his portrayal of local figures within their environment.

The Elephant (1822): A work from his Calcutta period, showing his ability to depict animals with accuracy and character.

Personal Life, Character, and Anecdotes

Chinnery's personal life was marked by complexity and instability. His marriage to Marianne Vigne was strained by his long absences and financial irresponsibility; she and their children eventually joined him in India for a period, but the relationship remained difficult, and she ultimately returned to Ireland. He was known to have had other relationships and possibly illegitimate children in India. His elder brother, William Chinnery, became embroiled in a major financial scandal involving embezzlement from the British Treasury, eventually fleeing to Sweden, which may have cast a shadow over the family name.

George Chinnery himself was perpetually in debt, a primary motivation for his successive moves from Dublin to Madras, Calcutta, and finally Macau. He was described by contemporaries as eccentric, witty, and sociable, but also somewhat irascible and disorganized in his personal affairs. His adoption of the Gurney shorthand system, primarily for annotating his sketches, links him intriguingly to another famous user of the system, Charles Dickens, though there is no evidence they ever met. The shorthand adds a layer of intimacy and immediacy to his drawings. Despite his financial woes, he maintained a productive artistic practice until the end of his life.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

George Chinnery occupies a significant, if sometimes overlooked, place in art history. He was arguably the most important British artist working in Asia in the first half of the nineteenth century. His work provides an unparalleled visual record of Anglo-Indian society in Madras and Calcutta, and even more uniquely, of life in the Pearl River Delta during the era of the Canton System. His depictions of Macau and Canton are crucial historical documents.

His role as a bridge between Eastern and Western artistic traditions is paramount. Unlike earlier court painters like the Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining) who adapted to Chinese tastes within the Imperial court centuries earlier, Chinnery brought the contemporary British academic style directly into the bustling port cities and taught it to local artists like Lam Qua, fostering a hybrid style that catered to the emerging global market. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of the leading artists in Europe, his skill, dedication to observation, and unique geographical focus make his work distinctive and important.

Although his reputation in Britain waned after his departure and he was largely forgotten there for a time, his work has gained increasing recognition. Major collections worldwide now hold his paintings and drawings, including the Yale Center for British Art, the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the Macau Museum, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, and the National Portrait Gallery in London. Numerous exhibitions, such as those held in Hong Kong (1985, 2005) and Macau (1997, 2024), have shed light on his career and contributions.

Conclusion: An Enduring Eye on the East

George Chinnery died in Macau on May 30, 1852, and was buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery there, alongside many of the merchants and missionaries he had painted. His life was one of constant movement, often driven by the need to escape debt, yet this peripatetic existence placed him in the unique position of witnessing and documenting societies undergoing profound change at the intersection of global empires and trade routes. Through thousands of portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes executed with skill and sensitivity across India and China, Chinnery left behind a rich visual legacy. He remains a key figure for understanding not only the art of the period but also the complex cultural encounters that shaped the modern world. His enduring eye captured the people and places of the East with an intimacy and insight that continues to resonate today.