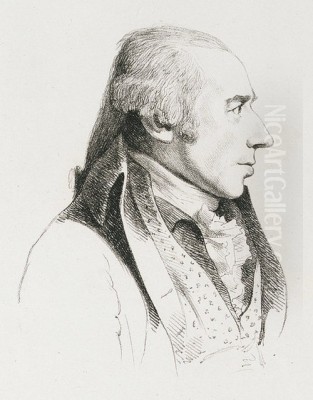

William Hodges stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of eighteenth-century British art. Born in London on October 28, 1744, into an era brimming with exploration and burgeoning scientific inquiry, Hodges carved a unique path that merged the roles of artist and explorer. His life (1744-1797) spanned a period of immense global change, and his canvases became vital documents, offering European audiences unprecedented glimpses into the Pacific islands and the Indian subcontinent. Trained by one of Britain's foremost landscape pioneers, Hodges developed a distinctive style characterized by dramatic light and atmospheric sensitivity, applying European artistic conventions to radically unfamiliar terrains. His journeys, particularly with Captain James Cook and later through India, not only produced a remarkable body of work but also contributed significantly to the visual culture of the British Empire and the evolution of landscape painting itself.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

William Hodges emerged from humble beginnings in London, the son of a blacksmith. This background perhaps instilled in him a practical sensibility that would later serve him well in the demanding conditions of global voyages. His formal artistic education began under the tutelage of William Shipley, whose drawing school in the Strand was a notable institution fostering young talent. Shipley's academy emphasized practical skills and observation, providing a solid foundation for Hodges's future endeavours.

The most formative influence on Hodges's early career, however, was his time spent in the studio of Richard Wilson (c. 1713-1782). Wilson, often hailed as one of the founding fathers of British landscape painting, brought the classical landscape tradition, inspired by artists like Claude Lorrain, to Britain. He adapted its principles to depict Welsh and Italian scenery with a unique sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Working as Wilson's assistant and pupil, Hodges absorbed not only technical skills in oil painting but also Wilson's approach to composition, his handling of light, and his elevation of landscape as a serious genre. This training under Wilson provided Hodges with the artistic language he would later adapt and transform when confronted with the vastly different landscapes of the tropics and the East.

The Pacific Voyage with Captain Cook

A pivotal chapter in Hodges's life began in 1772 when he was appointed by the Admiralty as the official landscape painter for Captain James Cook's second great voyage of exploration to the Pacific Ocean (1772-1775). Sailing aboard the HMS Resolution, alongside its companion ship HMS Adventure, Hodges was tasked with a specific mission: "to make drawings and paintings of such places... as may be of use to navigation; and also to paint portraits of the inhabitants, and views of the country." This appointment marked a significant moment, integrating a professional artist focused on landscape into the core team of a major scientific and exploratory expedition.

During the three-year circumnavigation, Hodges worked tirelessly under often challenging conditions. He documented the expedition's encounters with diverse lands and peoples, creating sketches and paintings that captured the dramatic coastlines, lush vegetation, and unique atmospheric conditions of locations previously unknown or only vaguely imagined by Europeans. His subjects included the idyllic shores of Tahiti, the monumental statues (Moai) of Easter Island, the dramatic fjords of Dusky Bay in New Zealand, the tropical islands of Tonga and New Caledonia, and even the icy, ethereal landscapes encountered during the expedition's pushes towards the Antarctic Circle. He became the first European artist to provide visual records of many of these places.

Hodges's role extended beyond mere topographical accuracy. He was expected to create finished works that would convey the spirit and significance of the discoveries to the British public and Admiralty upon return. His sketches made in situ, often rapid notations of light and form, formed the basis for more elaborate oil paintings and watercolours completed either on board or back in his London studio. This practice also positions Hodges as an early proponent of plein air (outdoor) sketching, adapting his techniques to capture fleeting effects of light and weather. Through this voyage, Hodges earned the distinction of being arguably the first professional landscape artist to circumnavigate the globe.

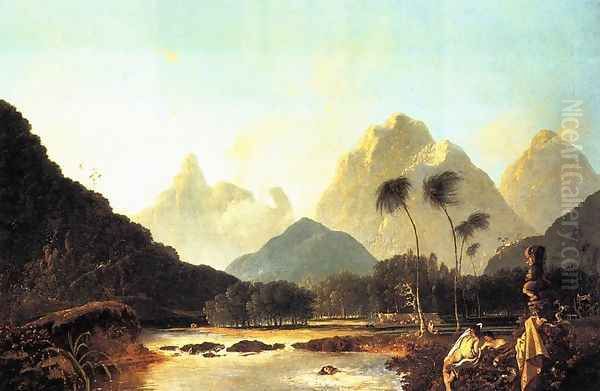

Artistic Vision of the Pacific

The body of work resulting from Cook's second voyage cemented Hodges's reputation and offered a startling new vision of the world. His Pacific landscapes are notable for their innovative approach to light and atmosphere. He moved beyond the conventions of the European picturesque, striving to capture the unique qualities of tropical light – its intensity, its warmth, and its dramatic interplay with clouds and water. Works like A View taken in the Bay of Oate Peha, Valipetiha, Otaheite, Tahiti Revisited (1776) exemplify this, showcasing a luminous sky and calm waters reflecting the warm glow, while carefully rendering the volcanic terrain and local flora.

Hodges often employed strong contrasts between light and shadow to heighten the drama and convey the sublime power of nature, particularly evident in his depictions of stormy seas or the imposing landscapes of New Zealand's Dusky Bay. His paintings of the Antarctic ice fields were revolutionary, capturing the otherworldly blues and whites and the immense scale of the frozen wilderness, subjects entirely new to European art.

While grounded in observation, Hodges's Pacific works also reflect the artistic sensibilities of his time. He sometimes employed classical compositional structures learned from Richard Wilson and invoked the spirit of artists like Claude Lorrain or Salvator Rosa to lend grandeur and familiarity to these exotic scenes. His depictions of indigenous peoples, such as his portrait of the Tahitian chief Honu, often blended ethnographic detail with a classicizing tendency, presenting them with a certain nobility. His famous painting The Monuments of Easter Island combines topographical record with a sense of mystery and the sublime, emphasizing the scale and antiquity of the Moai against a dramatic sky. These works were instrumental in shaping European perceptions of the Pacific, offering visually compelling, if sometimes idealized, narratives of exploration and encounter.

The Indian Sojourn

Following his return from the Pacific and a period consolidating his reputation in London, Hodges embarked on the second major journey of his career. Around 1778 or 1779 (sources vary slightly, often cited as 1780-1784 for his main working period there), he travelled to India, becoming the first professional British landscape painter to work extensively on the subcontinent. This venture was undertaken with the support and patronage of the East India Company, particularly Warren Hastings, the Governor-General of Bengal. Hastings was known for his interest in Indian culture and commissioned several works from Hodges.

Based primarily in Calcutta (Kolkata) and travelling extensively, including journeys up the Ganges river to cities like Benares (Varanasi) and Lucknow, Hodges immersed himself in documenting the Indian landscape, architecture, and, to some extent, local life. India presented a different set of visual challenges and opportunities compared to the Pacific. Here, Hodges encountered ancient and complex architectural traditions, bustling cities, vast river systems, and the distinct light and atmosphere shaped by the monsoon climate.

His time in India was highly productive. He created numerous oil paintings, watercolours, and sketches depicting famous Mughal and Hindu monuments, river scenes, forts, and cityscapes. These works provided British audiences with some of the earliest professional artistic renderings of the Indian scene, moving beyond the amateur sketches of Company officials or the purely topographical work of military draftsmen. His painting Mrs. Hastings Near the Rocks of Colong (c. 1790), likely completed after his return but based on Indian studies, shows his ability to integrate figures into evocative landscapes, capturing a specific sense of place.

Depicting India: Light, Architecture, and Influence

Hodges's Indian works display a continued fascination with the effects of light, adapted now to the specific conditions of the subcontinent. He captured the hazy heat of the plains, the dramatic skies of the monsoon season, and the way sunlight interacted with intricate architectural surfaces. His depictions of buildings like the Taj Mahal, mosques in Benares, or forts along the Ganges are noted for their attention to architectural detail combined with a powerful sense of atmosphere. He sought to convey not just the appearance but the feeling of these places – their grandeur, antiquity, and exoticism.

His approach often blended topographical accuracy with picturesque conventions, sometimes enhancing the drama or romantic appeal of a scene. He was particularly interested in the textures and forms of Indian architecture, seeing in them historical depth and aesthetic value. His work provided a visual vocabulary for representing India that would influence subsequent generations of artists travelling to the region, most notably Thomas Daniell and his nephew William Daniell, whose own aquatints of Indian scenery achieved widespread popularity.

Hodges's Indian paintings played a crucial role in shaping British understanding and imagination of India during a period of expanding colonial influence. They offered images of a land rich in history, culture, and monumental beauty, contributing to the complex and often contradictory ways Britain viewed its growing empire in the East. His work helped establish India as a subject worthy of serious artistic attention within the British school.

Publications and Theoretical Contributions

Beyond his painted canvases, William Hodges sought to share his experiences and artistic ideas through publication. After his return from India, he produced Select Views in India (1785-1788), a series of aquatint prints based on his drawings and paintings. Aquatint, a technique capable of rendering tonal variations similar to watercolour, was well-suited to reproducing the atmospheric effects Hodges prized. These prints circulated widely, further disseminating his vision of India to the British public and fellow artists.

Hodges also harboured theoretical ambitions, particularly concerning architecture. In 1793, he published A Dissertation on the Prototypes of Architecture: Hindu, Moorish, and Gothic. In this text, drawing upon his observations in India and his knowledge of European styles, Hodges argued for a common origin or underlying principle connecting these seemingly disparate architectural traditions. He speculated on the influence of natural forms, like timber construction or cave dwellings, on later stone architecture across different cultures. While his theories were speculative and rooted in the comparative methodologies of his time, the Dissertation reflects his intellectual curiosity and his desire to place his artistic observations within a broader historical and theoretical framework. It stands as a testament to his engagement with the cultures he encountered, moving beyond purely visual representation.

Relationship with the Royal Academy and Contemporaries

William Hodges's standing within the London art world was formally recognized through his association with the Royal Academy of Arts. He exhibited works there regularly from the 1770s onwards, showcasing his paintings from the Pacific and India. In 1787, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), and in 1789, he achieved the status of full Academician (RA). This placed him among the established figures of the British art scene, alongside contemporaries like the Academy's president Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Benjamin West, and Angelica Kauffman.

While an Academician, Hodges's primary influence stemmed more from the novelty and power of his travelled landscapes than from direct involvement in the Academy's administration or teaching. His work, however, resonated with certain artistic currents of the time. His emphasis on light and atmosphere, particularly in his later Indian works, prefigured some of the concerns that would preoccupy later Romantic landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. Turner, in particular, is known to have admired Hodges's handling of light.

Hodges also engaged, sometimes critically, with the prevailing tastes in landscape design. His 1794 solo exhibition included works implicitly critiquing the popular landscape gardening styles of Lancelot "Capability" Brown and Humphry Repton, suggesting his own, perhaps more rugged or naturalistic, ideals. His relationship with Sir Joshua Reynolds seems to have been one of mutual respect within the Academy structure, sharing perhaps a broad commitment to the 'grand style' and the importance of artistic judgment, even as Hodges applied these ideas to unconventional subject matter. He existed within a landscape tradition that included the topographical work of artists like Paul Sandby and the dramatic proto-Romanticism of Joseph Wright of Derby, carving out his own niche through his focus on exotic locales.

Style and Technique: Light, Colour, and Controversy

Hodges's artistic style is most consistently defined by his masterful manipulation of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and his sensitivity to atmospheric effects. Whether depicting the clear, bright light of the Pacific or the hazy, intense heat of India, light is often the true subject of his paintings. He used colour boldly, sometimes employing strong contrasts and a warm palette to convey the vibrancy of tropical environments. His technique involved building up layers of paint, often using glazes to achieve luminosity and depth.

His training under Richard Wilson provided a foundation in classical composition, but Hodges adapted these principles freely to suit his subjects. He was less interested in the formulaic picturesque favoured by some contemporaries and more focused on capturing the specific character and mood of a place. This sometimes led to works that felt unconventional to eighteenth-century eyes.

Indeed, Hodges's style was not without its critics. Some contemporaries found his handling of paint occasionally "coarse" or his compositions lacking in conventional "finish." His bold colour contrasts and dramatic lighting could be seen as violating neoclassical ideals of harmony and restraint. His 1794 solo exhibition, featuring allegorical landscapes commenting on themes like peace and war alongside his architectural critiques, proved particularly controversial. Held during the politically charged atmosphere following the French Revolution, the exhibition was poorly received and quickly closed, partly due to accusations that its themes were "seditious" or "inflammatory." This event marked a downturn in his public career.

Later Years, Legacy, and Art Market Presence

The closure of his 1794 exhibition and the ensuing criticism seemed to dampen Hodges's artistic ambitions. In the last few years of his life, perhaps seeking financial stability, he shifted his focus away from painting. He moved to Dartmouth and, somewhat unexpectedly, opened a small bank in partnership. Unfortunately, this venture proved disastrous. The bank failed amidst the financial instability of the war years with France. Deeply affected by this failure and reportedly in poor health, William Hodges died suddenly on March 6, 1797, at the age of 52. Contemporary accounts suggest the circumstances pointed towards suicide induced by despair over his financial ruin.

Despite this tragic end and periods of relative neglect, Hodges's legacy has endured and grown over time. He holds a crucial place as a pioneer of expeditionary art, demonstrating the vital role an artist could play in documenting and interpreting global exploration. His works provided invaluable source material for understanding the Pacific and India in the late eighteenth century. He significantly expanded the subject matter of British landscape painting, proving that exotic locales could be treated with the same seriousness and artistic ambition as European scenes.

His innovative use of light and atmosphere had a demonstrable impact on later artists, most notably J.M.W. Turner. While sometimes overshadowed by the Daniells in the popular imagination of India, or by Cook himself in the narrative of Pacific exploration, modern scholarship increasingly recognizes Hodges's unique contribution and artistic merit. He is now seen as one of the most significant British landscape painters of his generation, a bridge between the classical tradition of Wilson and the burgeoning Romantic movement.

His works continue to be valued in the art market. Paintings and prints by Hodges appear at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Bonhams. For example, his View of Port Louis, Mauritius from the sea significantly exceeded its estimate at a 2021 Sotheby's sale, fetching over £300,000. A first edition print of the Taj Mahal from his Select Views in India sold for over £30,000 at Bonhams in 2011. While prices fluctuate, these results indicate a sustained interest among collectors and institutions in acquiring works by this important artist-explorer.

Conclusion: An Artist Between Worlds

William Hodges occupies a unique and fascinating position in art history. He was an artist poised between worlds: between the classical landscape tradition and emerging Romanticism, between the familiar scenery of Britain and the startling novelty of the Pacific and India, between the demands of scientific documentation and the impulses of artistic expression. His journeys with Cook and through India placed him at the forefront of Britain's engagement with the wider world, and his art became a primary means through which that world was visualized and understood back home.

Though his career faced challenges and ended prematurely, Hodges produced a body of work remarkable for its scope, ambition, and innovation. His sensitivity to light, his willingness to adapt his style to capture the essence of unfamiliar environments, and his role as a visual chronicler of exploration secure his importance. More than just a painter of places, William Hodges was an artist who expanded the horizons of British art, leaving behind a compelling visual record of a world undergoing profound transformation.