Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of British art, renowned primarily for his extensive and influential depictions of the landscapes, architecture, and antiquities of India. Working often in close collaboration with his nephew, William Daniell, Thomas embarked on a remarkable journey through the East at a time when such travels were arduous and uncommon for European artists. His work not only introduced the visual splendours of the Indian subcontinent to a Western audience with unprecedented detail and scope but also significantly shaped the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the Picturesque movement and contributed to the complex visual culture of Orientalism. His legacy is preserved in a vast body of work, most notably the monumental aquatint series Oriental Scenery, which remains a cornerstone for understanding both late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century British art and European perceptions of India.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in Kingston upon Thames in 1749, Thomas Daniell came from relatively modest beginnings, the son of an innkeeper at Chertsey, Surrey. His artistic inclinations led him away from the family trade. Details of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, but it is known that he was apprenticed to a heraldic painter, a craft which would have instilled a discipline for precision and detail. He further honed his skills by studying at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London, enrolling in 1773. This period provided him with formal training in drawing and painting, exposing him to the prevailing artistic currents of the time.

During the 1770s and early 1780s, Daniell began to establish himself within the London art scene. He exhibited landscape paintings at the Royal Academy, starting in 1772 and continuing intermittently until 1784. These early works primarily depicted British scenery, reflecting the influence of established landscape painters such as Richard Wilson, known for his classical compositions, and Paul Sandby, a pioneer in watercolour and topography. However, Daniell struggled to achieve significant recognition or financial success in the competitive London market, which was dominated by portraitists like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, and increasingly, by established landscape artists.

This lack of significant breakthrough in Britain likely played a role in his decision to seek opportunities further afield. India, under the expanding influence of the British East India Company, presented the prospect of new patronage among the British expatriate community and the allure of novel, exotic subject matter that could distinguish his work upon return. The desire for fresh inspiration and a unique artistic niche was a powerful motivator.

The Voyage East and Initial Years in India

In 1785, Thomas Daniell made the momentous decision to travel to India. Crucially, he obtained permission from the East India Company to sail aboard the Indiaman Atlas. Accompanying him was his young nephew, William Daniell (1769-1837), then only about sixteen years old, who would serve as his assistant, apprentice, and eventual collaborator. This partnership would prove to be one of the most fruitful in the history of British topographical art. Their journey took them first to China, specifically via the trading post at Whampoa near Canton (modern Guangzhou), where they spent several months in late 1785. This brief interlude allowed them to make sketches of Chinese landscapes and port life, experiences that would later inform some of their published works.

The Daniells arrived in Calcutta (modern Kolkata), the administrative heart of British India, by ship in early 1786. Calcutta was a bustling, rapidly growing city, a hub of colonial power and commerce. Thomas quickly set about establishing himself, initially undertaking portrait commissions to secure an income. However, his primary interest lay in landscape and topography. Recognizing a market for views of the colonial capital among its European residents, he embarked on a significant early project: a series of twelve aquatint views titled Views of Calcutta.

Published between 1786 and 1788, the Views of Calcutta were meticulously executed and proved highly successful. They depicted the city's prominent colonial architecture, bustling ghats (steps leading down to the river), and street scenes, rendered with a clarity and precision that appealed to the desire for accurate representations of the burgeoning British presence. This project not only provided financial stability but also established Thomas Daniell's reputation in India as a skilled topographical artist and master of the aquatint medium, which adeptly replicated the tonal subtleties of watercolour washes. It laid the groundwork for their more ambitious travels into the interior.

Grand Tours Through the Subcontinent

The success of the Calcutta views emboldened Thomas Daniell to venture beyond the colonial capital and explore the vast, diverse landscapes and ancient monuments of India. Between 1788 and 1791, Thomas and William undertook a series of extensive and often arduous journeys, documenting regions rarely seen by European eyes. These tours were remarkable feats of endurance and artistic dedication, involving travel by boat, palanquin, and on foot through challenging terrain and climates.

Their first major tour took them northwards up the Ganges River valley, starting in August 1788. They travelled through Bengal and into Hindustan, visiting key cities and sites such as Murshidabad, Bhagalpur, Patna, Benares (Varanasi), Allahabad, Cawnpore (Kanpur), and Lucknow. Along the way, they sketched prolifically, capturing river landscapes, bustling ghats teeming with life, ancient temples, mosques, and forts. They relied heavily on watercolour sketches made on the spot, often utilizing a camera obscura – an optical device that projected an image onto paper – to aid in achieving topographical accuracy in their outlines.

A second tour pushed further north-west towards the heartland of the former Mughal Empire. They visited Agra, where they meticulously documented the Taj Mahal and other Mughal architectural marvels, and travelled to Delhi, the historical Mughal capital, sketching its monuments and ruins. They also explored sites like Mathura and Brindaban, important centres of Hindu pilgrimage. These journeys provided them with an unparalleled visual archive of India's rich architectural heritage.

Perhaps their most adventurous expedition was the third tour, undertaken in 1789, into the Garhwal region of the Himalayas. They travelled up to Srinagar (in Garhwal, not Kashmir) and Joshimath, becoming among the very first European artists to penetrate and depict this dramatic mountain landscape. Sketches from this trip captured towering peaks, deep gorges, precarious rope bridges, and remote temples, conveying a sense of sublime nature that contrasted with the architectural focus of their other work. This pioneering journey into the Himalayas added a unique dimension to their portfolio.

Journey South and Return to Britain

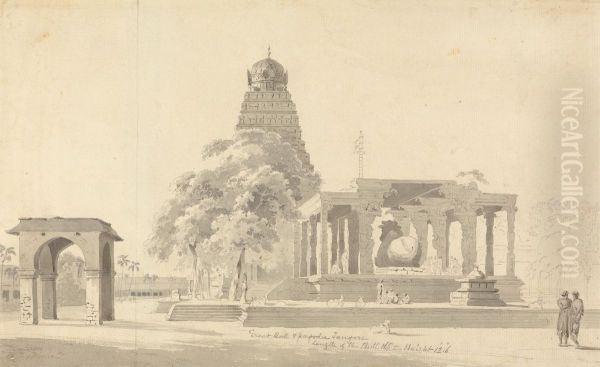

Following their extensive explorations of Northern India, the Daniells turned their attention southwards. They travelled overland and possibly by sea to Madras (modern Chennai) on the Coromandel Coast. From there, they made excursions into the surrounding regions, including Mysore, which had recently been the theatre of conflict between the British and Tipu Sultan. Their focus in the south shifted towards the region's distinctive Dravidian temple architecture and ancient rock-cut monuments, such as the Shore Temple and the monolithic raths at Mahabalipuram (Seven Pagodas). These sites offered a different, but equally compelling, vision of India's ancient past.

Their time in India spanned nearly seven years, a period of intense activity and observation. In 1793, their path took them back towards China. They managed to associate themselves, albeit perhaps somewhat opportunistically rather than as official artists, with the Macartney Embassy, Britain's first diplomatic mission to the Imperial Court in Beijing. While the embassy ultimately failed in its main diplomatic objectives, the Daniells used the opportunity during the journey and brief stays in places like Canton to gather further sketches of Chinese scenery and life. This added another layer to their extensive visual record of the East.

Finally, in 1794, Thomas and William Daniell embarked on their return voyage to England. They carried with them an extraordinary collection of sketches, drawings, notes, and perhaps some finished paintings – the raw material for what would become their most significant contribution to art and the European understanding of India. Their decade-long immersion in the East had equipped them with unique subject matter and a profound, firsthand understanding of the lands they depicted.

Oriental Scenery: The Magnum Opus

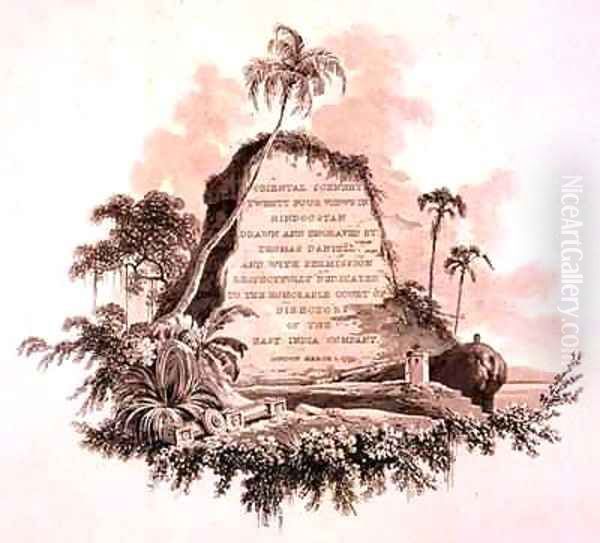

Upon their return to London in 1794, Thomas Daniell, with the crucial assistance of William, began the monumental task of translating their vast collection of field sketches into a form suitable for publication and wide dissemination. The result was Oriental Scenery, arguably the most ambitious and influential series of aquatint views of India ever produced. Published in six parts between 1795 and 1808, the complete work comprised 144 hand-coloured aquatints, accompanied by descriptive text.

The aquatint process was key to the project's success. This intaglio printmaking technique allowed for the creation of broad tonal areas, effectively mimicking the appearance of watercolour washes. Thomas was a master of the medium, and William became highly proficient under his tutelage, often undertaking much of the laborious engraving work himself. The prints were then carefully hand-coloured, often by teams of colourists, resulting in images of exceptional beauty and detail that captured the light, atmosphere, and texture of the Indian scenes.

Oriental Scenery presented a comprehensive panorama of India. It included views of landscapes ranging from the Himalayan foothills to the plains of the Ganges and the coasts of the south. It showcased magnificent Mughal tombs and mosques, elaborate Hindu temples, ancient rock-cut caves like those at Ellora (which they documented in a separate related publication, Hindoo Excavations in the Mountain of Ellora), colonial buildings in Calcutta, and scenes of daily life. The scale and scope of the project were unprecedented, offering a visual encyclopaedia of India that captivated the British public.

The publication was a resounding success, both critically and commercially. It cemented the Daniells' reputation and brought them considerable financial reward. More importantly, Oriental Scenery profoundly influenced British perceptions of India, presenting it as a land of ancient grandeur, picturesque beauty, and exotic allure. It became a standard visual reference for India, influencing architects, designers, writers, and other artists for decades. It overshadowed the work of earlier artists who had depicted India, such as William Hodges, whose style was often considered more dramatically atmospheric but less topographically precise than that of the Daniells.

Artistic Style, Technique, and the Picturesque

Thomas Daniell's artistic style was fundamentally rooted in the British topographical tradition, emphasizing accuracy and detailed observation. His training and early work provided a solid foundation in draughtsmanship, particularly in architectural rendering. His use of the camera obscura during his travels further reinforced this commitment to capturing the precise forms of buildings and landscapes. Yet, his work was not merely documentary; it was filtered through the prevailing aesthetic of the Picturesque.

Popularized by theorists like William Gilpin and Uvedale Price, the Picturesque aesthetic valued landscapes that exhibited qualities such as roughness, irregularity, variety, and visual interest – scenes that would look appealing in a picture. Daniell often subtly composed his views to enhance these qualities, framing scenes with foliage, positioning figures strategically to add scale or narrative interest, and sometimes adjusting topographical features for better compositional balance. He drew inspiration from classical landscape painters like Claude Lorrain, known for his idealized, light-filled compositions, and Salvator Rosa, admired for his wilder, more rugged scenes.

Daniell demonstrated a remarkable sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His Indian views often capture the specific quality of light at different times of day, from the cool clarity of morning to the warm glow of sunset. His watercolours, which formed the basis for the aquatints, possess a freshness and immediacy, while his oil paintings allowed for richer colour and more complex atmospheric effects. His skill extended to rendering the textures of stone, foliage, and water, bringing his scenes to life.

While William Daniell developed his own distinct style over time, often favouring broader effects and maritime subjects later in his independent career, the works produced during their Indian collaboration show a remarkable consistency, largely guided by Thomas's established approach. Their joint output represents a masterful blend of careful observation and artistic sensibility, creating images that were both informative and aesthetically pleasing to their contemporary audience.

Later Career, Recognition, and Other Works

The success of Oriental Scenery secured Thomas Daniell's position within the British art establishment. He continued to paint and exhibit, drawing on his vast stock of Indian sketches for new compositions in oil and watercolour. He also produced views of British scenery, returning to the subjects of his youth, but it was his Oriental subjects that remained his primary focus and source of renown.

Recognition from his peers followed. Thomas Daniell was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1796 and achieved the distinction of becoming a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1799. William was elected RA later, in 1822. Thomas exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy exhibitions until 1828, showcasing large oil paintings based on his Indian travels, which were often praised for their accuracy and grandeur.

Beyond Oriental Scenery, the Daniells collaborated on other publications, though William often took the lead in the later projects. A Picturesque Voyage to India by the Way of China (1810) featured aquatints based on their journey eastwards. They also published Antiquities of India (1799-1808) and the aforementioned Hindoo Excavations in the Mountain of Ellora (1803), focusing more specifically on architectural and archaeological subjects. Thomas also contributed designs to publications on landscape gardening, reflecting his engagement with the Picturesque aesthetic in Britain.

Compared to other European artists working in India during the same period, such as the portraitist Johann Zoffany or the earlier landscape painter Tilly Kettle, the Daniells' contribution was unique in its scope and focus on topography and landscape rendered through the accessible medium of aquatint. Later artists like George Chinnery would focus more on port scenes and local life in India and China, while James Baillie Fraser would follow in the Daniells' footsteps exploring Himalayan regions, clearly influenced by their pioneering work.

Thomas Daniell, Orientalism, and Empire

Thomas Daniell's work is inextricably linked to the historical context of British expansion in India and the broader cultural phenomenon of Orientalism – the way Western cultures represented and understood the East. His depictions, while striving for accuracy, inevitably presented a particular vision of India, one that resonated with European tastes and, often implicitly, with the colonial project.

His focus on ancient monuments, majestic landscapes, and seemingly timeless scenes of traditional life tended to emphasize India's past grandeur and picturesque qualities, sometimes at the expense of depicting the complexities and disruptions of contemporary life under burgeoning colonial rule. While not overtly propagandistic, the images often presented India as a passive, beautiful land, ripe for appreciation and, by implication, administration by the British. The careful rendering of Mughal and Hindu architecture could be seen as documenting a glorious past that, in the colonial narrative, had declined, justifying British intervention.

However, interpreting his work solely through the lens of colonial ideology is overly simplistic. Daniell displayed a genuine fascination with and respect for Indian architecture and culture. His meticulous documentation preserved records of sites that have since changed or decayed. His images, particularly those in Oriental Scenery, provided a visual richness and detail that went far beyond earlier, often cruder, European representations of the East. His work undeniably shaped how generations of Europeans visualized India, contributing significantly to the "imagined geography" of the Orient.

Legacy and Influence

Thomas Daniell died in Kensington, London, in 1840, having lived a long and remarkably productive life. His legacy is substantial and multifaceted. He, along with William, pioneered the detailed topographical depiction of India on an unprecedented scale, setting a standard for accuracy and artistic quality. Oriental Scenery remains a landmark achievement in printmaking and topographical art, valued by art historians, historians of India, and collectors alike.

His influence extended to subsequent generations of artists. British artists travelling to India and the East in the 19th century often worked in the shadow of the Daniells, using their views as reference points or seeking to emulate their success. His work also had an impact on architectural and decorative arts in Britain during the Regency period, contributing to the taste for "Hindoo" styles in architecture and design, most famously exemplified by the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, although its architect John Nash drew from a variety of sources.

While later landscape artists in Britain, such as J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, pursued different, more Romantic or naturalistic paths in depicting their native scenery, Daniell's work remains significant within the specific context of British landscape art related to travel and empire. His careful observation, combined with a Picturesque sensibility, created a body of work that functions simultaneously as historical documentation (albeit selective) and compelling artistic creation. His views continue to offer valuable insights into the landscapes and monuments of India as they appeared over two centuries ago, filtered through the eyes of a dedicated and highly skilled British artist.

Conclusion

Thomas Daniell was more than just a painter of foreign lands; he was a visual interpreter who bridged cultures, bringing the landscapes and architectural wonders of India and the East into the European consciousness with remarkable fidelity and artistry. His extensive travels with his nephew William, undertaken with great determination, resulted in an unparalleled visual record. Through the masterful use of the aquatint medium in Oriental Scenery and other works, he created images that were both informative and deeply imbued with the aesthetic ideals of the Picturesque. While his work can be situated within the complex history of Orientalism and British colonialism, its enduring power lies in its meticulous detail, atmospheric beauty, and the sheer ambition of its scope. Thomas Daniell remains a crucial figure for understanding the intersection of art, travel, and empire in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, leaving behind a rich visual legacy that continues to fascinate and inform.