William Kay Blacklock (1872-1924) stands as a notable figure in British art during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Primarily known for his evocative watercolours and oils, Blacklock dedicated his artistic career to capturing the quiet charm and gentle rhythms of English rural life, often focusing on domestic scenes featuring women and children. Though his life was relatively short, his work offers a valuable window into the aesthetics and social values of his time, showcasing technical proficiency and a sensitive eye for light and detail.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in the bustling industrial town of Sunderland in the North East of England in 1872, William Kay Blacklock's origins were modest. His father, John Blacklock, worked as a mechanic, and his mother was Isabella Blacklock. The practicalities of life in a working-class family in industrial Britain likely shaped his early experiences, perhaps fostering an appreciation for the perceived tranquility of the countryside that would later dominate his art.

Precise details about his earliest education are scarce, but a significant turn occurred following his father's death. Facing the need to support himself, the young Blacklock did not immediately pursue fine art full-time. Instead, according to the 1891 census, he became an apprentice lithographer. This training, while commercial, would have provided him with a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, precision, and the handling of tone – skills that undoubtedly benefited his later painting career.

Despite the demands of his apprenticeship, Blacklock's passion for painting persisted. He continued to develop his artistic talents, likely studying in his spare time. His ambition eventually led him away from Sunderland. Around 1901, seeking greater opportunities and more formal training, he made the pivotal move to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world.

Formal Training and Emergence as an Artist

In London, Blacklock enrolled at the prestigious Royal College of Art (RCA). Studying at the RCA provided him with rigorous academic training, honing his skills in drawing, composition, and the use of different media, particularly oil and watercolour. This period was crucial for refining his technique and establishing his artistic direction. The curriculum would have exposed him to traditional methods while also allowing him to engage with the prevailing artistic currents of the day.

His talent began to gain recognition relatively quickly. Blacklock started exhibiting his work professionally while still associated with the RCA. Records show that he exhibited a total of seventeen works at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) between 1897 and 1918. The RA was the preeminent venue for artists seeking establishment recognition in Britain, and consistent inclusion in its summer exhibitions was a significant mark of success. He also exhibited frequently with other major institutions, including the Royal Institute of Oil Painters (ROI), where he showed fifteen works, demonstrating his proficiency and commitment to oil painting alongside his watercolour practice.

These exhibitions placed his work before a wide audience and situated him within the broader landscape of contemporary British art. His participation indicates that his style, focusing on carefully rendered scenes of rural life, found favour with the selection committees and resonated with the tastes of the time, which often leaned towards narrative, sentiment, and technical accomplishment.

Style and Subject Matter: The Rural Idyll

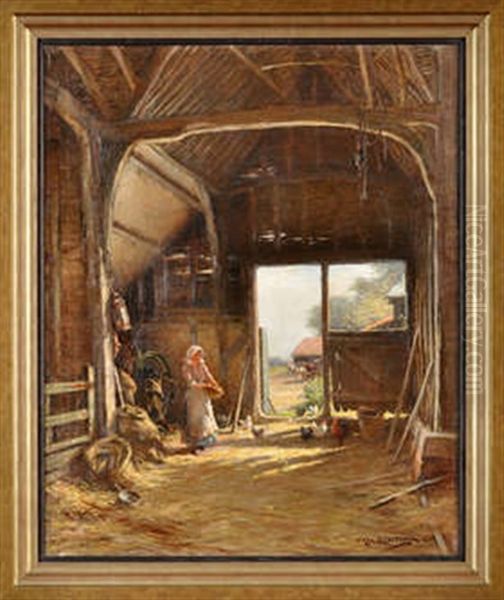

Blacklock's artistic output is characterized by a consistent focus on rural and domestic subjects. He gravitated towards scenes of pastoral life, village settings, farmsteads, and coastal communities. His paintings often depict figures, typically women and children, engaged in everyday tasks or quiet moments of contemplation within these settings. Works like The Shepherdess and A Lesson (also sometimes titled Needlework by the Window) exemplify this thematic concentration.

His style can be broadly categorized as Academic Realism with a strong leaning towards the sentimental and picturesque. He was a keen observer of detail, meticulously rendering textures, fabrics, and the play of light on surfaces. His handling of light, particularly sunlight filtering through windows or illuminating outdoor scenes, is often a key feature, creating atmosphere and highlighting focal points. This careful attention to verisimilitude aligns him with the academic traditions fostered by institutions like the RA and RCA.

However, Blacklock's realism is generally softened by an idealized, almost romantic sensibility. His depictions of rural life tend to emphasize harmony, simplicity, and quiet dignity, often avoiding the harsher realities that might have been present. His figures, particularly the women, are often portrayed with a gentle grace, embodying domestic virtues or a peaceful connection with nature. This approach reflects a common Edwardian nostalgia for a perceived simpler, pre-industrial past, offering viewers an escape from the complexities of modern urban life.

In watercolour, his technique was particularly adept. He demonstrated a fine control over washes, layering colours to achieve subtle tonal gradations and a luminous quality. In oils, his brushwork was typically controlled and precise, building up forms and textures carefully. While not radically innovative in the manner of emerging modernist movements, his work displays a high level of craftsmanship and a clear artistic vision rooted in established traditions.

Life in Walberswick: An Artist's Haven

A significant chapter in Blacklock's life and career unfolded in the coastal village of Walberswick, Suffolk. After marrying Ellen Richardson in 1891 and initially settling in Chelsea, London, the couple later relocated to Walberswick. This picturesque village, with its harbour, beaches, heathland, and distinctive cottages, had become a popular destination for artists by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, forming a loose artists' colony.

The move to Walberswick provided Blacklock with an abundance of inspiration directly suited to his artistic inclinations. The surrounding landscapes, the quality of the East Anglian light, and the daily lives of the local inhabitants offered rich subject matter. Many of his most characteristic works likely date from this period, capturing the specific atmosphere and scenery of the Suffolk coast and countryside.

Life in Walberswick also placed him within a community of fellow artists. While specific collaborations aren't heavily documented, the presence of other painters would have provided opportunities for artistic exchange and mutual support. It is noted that his wife, Ellen, and their daughter frequently served as models for his paintings. This personal connection likely imbued his domestic scenes and figure studies with an added layer of intimacy and authenticity, even within their idealized framework. His paintings often feature interiors that feel observed and lived-in, suggesting studies made within his own home or the cottages of neighbours.

Artistic Context: Between Tradition and Naturalism

To fully appreciate William Kay Blacklock's contribution, it's essential to place him within the artistic context of his time. He worked during a period of transition in British art. The dominance of High Victorian academicism, represented by figures like Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema with their classical and historical subjects, was still felt, particularly at the Royal Academy. However, new influences were also gaining ground.

Blacklock's work aligns more closely with the current of Rural Naturalism that gained prominence in Britain from the 1880s onwards. This movement, influenced partly by French painters like Jean-François Millet and Jules Bastien-Lepage, focused on realistic depictions of rural labour and peasant life. British artists associated with this trend, such as George Clausen and Henry Herbert La Thangue, sought authenticity in their portrayal of the countryside, often emphasizing the effects of light and atmosphere studied outdoors (plein air).

While Blacklock shared the subject matter of rural life with these artists, his approach was generally less rugged and more polished than that of Millet or even some of his British contemporaries. His work often retains a more sentimental or picturesque quality compared to the sometimes starker realism of Clausen or La Thangue. He seems less concerned with social commentary on the hardships of rural labour and more focused on capturing the quiet beauty and domestic harmony of country living.

Another relevant context is the Newlyn School in Cornwall, whose members, including Stanhope Forbes, Frank Bramley, and Walter Langley, also focused on coastal and rural life, emphasizing realistic depiction and the effects of natural light. Although geographically separate, Blacklock's interest in similar themes and his careful rendering of light effects show a parallel sensibility. His later move to Polperro in Cornwall further connects him geographically, if not stylistically, to this artistic milieu.

Compared to the more experimental art emerging elsewhere in Europe, such as Post-Impressionism or Fauvism, Blacklock's work remained firmly rooted in representational traditions. He catered to a taste for well-crafted, accessible, and often reassuring images of national life. His contemporaries at the RA and other exhibiting societies included a wide range of artists, from traditional landscape painters like Benjamin Williams Leader to narrative genre painters like Marcus Stone or society portraitists like John Singer Sargent (an American working in London). Blacklock carved out his niche within this diverse scene, focusing consistently on his chosen themes. Other genre painters exploring domestic or rural themes included figures like Ralph Hedley in the North East or Elizabeth Adela Forbes (Stanhope Forbes' wife) in Newlyn.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Collections

Blacklock's consistent presence at major London exhibitions signifies a degree of professional success and acceptance within the mainstream art world of his day. Exhibiting seventeen works at the Royal Academy over two decades was a solid achievement, indicating that his work met the standards and appealed to the tastes favoured by the institution. His fifteen works shown at the Royal Institute of Oil Painters further underscore his standing as a professional artist proficient in multiple media.

Beyond London, his work likely appeared in regional exhibitions as well. The mention that his works are held in collections such as the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool confirms that his reputation extended beyond the capital and that public institutions acquired his paintings, recognizing their quality and representative nature. Works held in the collections of the Royal Academy and the Royal College of Art also attest to his connections with these key institutions.

While perhaps not reaching the level of fame or critical discussion accorded to the most prominent RAs or the more avant-garde figures of the era, Blacklock appears to have sustained a successful career as a painter of popular subjects. His work found a market among patrons who appreciated his skillful technique and his charming, often idyllic, portrayals of English life. The recurring themes of domesticity, motherhood, and peaceful rural landscapes held broad appeal in the Edwardian era.

Later Years and Death in Polperro

In his later years, Blacklock moved from Suffolk to another artists' haven: Polperro, a picturesque fishing village on the Cornish coast. Cornwall had long attracted artists drawn to its dramatic coastline, unique light, and traditional ways of life, famously hosting the Newlyn School. Polperro itself was a popular spot for painters.

Unfortunately, Blacklock's later life seems to have been marked by declining health. Details are scant, but sources indicate he suffered from poor health towards the end of his life. He died in Polperro in 1924 at the relatively young age of 52. His death cut short a career dedicated to the gentle depiction of rural England.

His wife, Ellen, survived him, and records indicate she was granted probate following his death. This confirms their marriage, correcting any contradictory accounts suggesting he remained unmarried. He left behind a body of work consistent in its themes and style, a testament to his focused artistic vision.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

William Kay Blacklock occupies a specific place in the narrative of British art. He was not a revolutionary figure who dramatically altered the course of painting, nor was he part of a defined avant-garde movement. Instead, he represents a significant strand of late Victorian and Edwardian art that valued technical skill, careful observation, and the depiction of reassuring, often sentimentalized, scenes of national life.

His primary contribution lies in his sensitive and skilled portrayal of English rural and domestic settings. He excelled at capturing the nuances of light, particularly the warm glow of sunlight in interiors or the dappled light of a country lane. His watercolours, in particular, are often praised for their delicacy and atmospheric quality. He possessed a genuine ability to render textures and details in a way that lent his scenes credibility, even within their idealized framework.

His focus on women and children within domestic or pastoral settings reflects common themes of the era, often emphasizing ideals of femininity, motherhood, and the perceived innocence of childhood and rural life. While modern viewers might critique the sentimentality or the potentially idealized view of labour and gender roles, these aspects are crucial for understanding the cultural values and artistic tastes of his time.

Historically, Blacklock might be seen as a competent and appealing minor master within the British genre painting tradition. He worked alongside, but perhaps slightly overshadowed by, contemporaries who pursued similar themes with greater vigour or social commentary, such as George Clausen or members of the Newlyn School like Stanhope Forbes or Walter Langley. He did not engage with the burgeoning modernist experiments that were beginning to challenge traditional representation, as seen in the work of artists associated with the Camden Town Group, like Walter Sickert or Spencer Gore, who were active in London during the latter part of Blacklock's career.

Nevertheless, Blacklock's work retains its charm and historical interest. His paintings offer a peaceful, beautifully rendered vision of a bygone England, captured with sincerity and considerable technical skill. They serve as valuable documents of a particular aesthetic sensibility and provide insight into the popular tastes of the Edwardian art market. His dedication to his craft and his consistent focus on the quiet beauty of everyday rural life ensure his place as a noteworthy artist of his generation. His works continue to be appreciated by collectors and enthusiasts of traditional British painting.

Conclusion

William Kay Blacklock's art provides a gentle immersion into the landscapes and interiors of late 19th and early 20th century England. From his beginnings as a lithographer's apprentice in Sunderland to his established career exhibiting at the Royal Academy and living amongst fellow artists in Walberswick and Polperro, he remained dedicated to a vision of rural and domestic tranquility. His skillful use of watercolour and oil, his particular sensitivity to light, and his focus on the quiet moments of everyday life define his contribution. While operating within the bounds of Academic Realism and the picturesque tradition, avoiding the social grit of some contemporaries and the innovations of modernism, Blacklock created a body of work that is both technically accomplished and evocative of its time. He remains a respected figure for those who appreciate the charm and craftsmanship of traditional British genre painting.