The annals of art history are filled with figures whose contributions, while significant, may not always achieve the widespread recognition of their most famous contemporaries. George Forster, an American painter active in the 19th century, is one such artist. Born in 1817 and passing away in 1896, Forster carved out a niche for himself, particularly in the realm of still life painting, a genre with a rich and enduring tradition in American art. His work, characterized by careful observation and a dedication to realistic representation, offers a window into the artistic currents and tastes of his time.

It is crucial, before delving into the life and work of the painter George Forster, to address a common point of confusion. He is often mistaken for his near-contemporary (in the broader historical sense, though their lifespans did not overlap significantly) Georg Forster (1754-1794), a prominent German naturalist, ethnologist, travel writer, journalist, and revolutionary. This Georg Forster accompanied Captain James Cook on his second voyage around the world and made substantial contributions to scientific literature and Enlightenment thought. The painter George Forster (1817-1896), the subject of this article, pursued a distinctly different path, dedicating his talents to the visual arts in America.

Biographical Sketch and Artistic Milieu

Details about George Forster's early life and artistic training are somewhat scarce, a common challenge when researching artists who were not at the absolute forefront of their era's fame. However, we know he was active as a painter during a vibrant period of American art. The 19th century in the United States saw the flourishing of the Hudson River School, with landscape painters like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, and later Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, capturing the grandeur of the American wilderness. Simultaneously, portraiture remained a staple, and genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, gained popularity.

Within this diverse artistic landscape, still life painting maintained a steady, if sometimes less heralded, presence. The tradition had been established earlier by figures like James Peale and Raphaelle Peale, sons of the polymath Charles Willson Peale. These artists brought a distinctly American sensibility to a genre that had European roots, particularly in 17th-century Dutch art. George Forster emerged into this continuing tradition, contributing his own meticulous approach to the depiction of inanimate objects.

Forster is known to have exhibited his work at prominent institutions, which indicates a degree of professional recognition. Records show his participation in exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia and the Boston Athenaeum. These venues were crucial for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and engage with the broader art community. PAFA, in particular, holds a distinguished place as the oldest art museum and school in the United States, and exhibiting there was a significant achievement.

The Art of Still Life: Forster's Focus

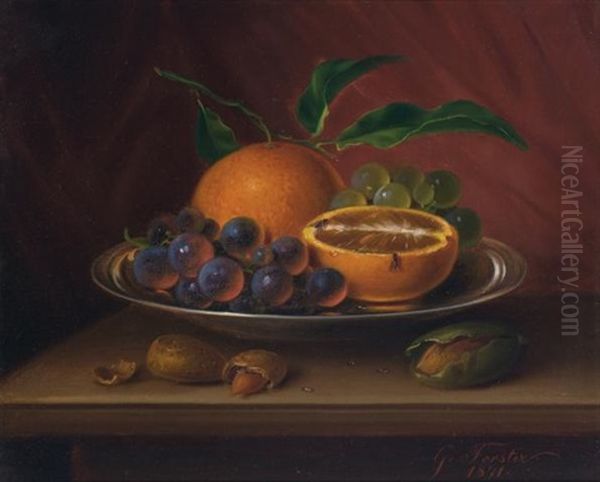

George Forster's reputation rests primarily on his still life compositions, especially those featuring fruit. This was a popular subgenre, allowing artists to showcase their technical skill in rendering textures, colors, and the play of light on various surfaces. Forster's approach was one of careful, detailed realism. His paintings often depict arrangements of fruit – luscious peaches, glistening grapes, ripe berries – sometimes accompanied by nuts or flowers.

A notable characteristic mentioned in relation to his work is the inclusion of minute details, such as dewdrops on fruit or, famously, a fly. The inclusion of insects, particularly flies, in still life paintings has a long history, dating back to early Netherlandish painting and carrying through the Dutch Golden Age with artists like Willem van Aelst or Jan Davidsz. de Heem. Such elements could serve multiple purposes: as a display of trompe-l'œil skill (literally "deceive the eye"), as a memento mori reminding viewers of the transience of life and earthly pleasures, or simply as an added touch of naturalism.

Forster’s dedication to this genre placed him in the company of other 19th-century American still life specialists. Artists like Severin Roesen, known for his abundant and elaborate fruit and flower compositions, and John F. Francis, who also specialized in fruit still lifes and luncheon pieces, were his contemporaries. Later in the century, the trompe-l'œil tradition would be taken to extraordinary heights by painters such as William Michael Harnett, John Frederick Peto, and John Haberle, whose hyper-realistic depictions of everyday objects, currency, and hunting gear captivated audiences. While Forster's work may not have reached the same level of illusionistic bravura as these later masters, his commitment to verisimilitude was evident.

Representative Works and Artistic Style

One of George Forster's most frequently cited works is a still life titled "Fruit, Nuts, and a Fly." While specific images and detailed analyses of a large corpus of his work can be elusive, this title itself is indicative of his thematic concerns and stylistic approach. The composition likely featured a carefully arranged assortment of fruit and nuts, rendered with Forster's characteristic attention to detail. The inclusion of the fly would have been a deliberate touch, inviting closer inspection and perhaps a subtle commentary on the nature of representation and reality.

His style can be described as precise and polished. He would have paid close attention to the local color of each object, the subtle gradations of tone that create a sense of volume, and the way light interacted with different surfaces – the soft bloom on a peach, the translucency of a grape, the hard sheen of a nutshell. This meticulousness aligns with the broader trends in American realism of the period, which valued accurate depiction and fine craftsmanship.

The term "American Impressionist painter" has been associated with Forster in some of the provided information. This attribution warrants careful consideration. American Impressionism, influenced by the French movement, gained traction in the United States primarily in the last two decades of the 19th century, with key figures like Mary Cassatt, Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and Theodore Robinson. Impressionism is characterized by its emphasis on capturing the fleeting effects of light and color, often with broken brushwork and an outdoor (en plein air) sensibility.

Given Forster's primary focus on detailed, realistic still lifes, which typically require controlled studio lighting and a high degree of finish, the "Impressionist" label seems less fitting for his core body of work. It is possible that in his later career, he may have experimented with looser brushwork or a brighter palette influenced by the burgeoning Impressionist movement, or perhaps he painted landscapes that adopted some Impressionistic qualities. However, his established reputation is built on the precision of his still lifes, which are more aligned with the traditions of realism than with Impressionism. Without specific late-career works demonstrating a clear shift, it's more accurate to situate him within the lineage of American realist still life painters.

Technique and Materials

Like most oil painters of his era, George Forster would have employed traditional techniques. This typically involved painting on canvas or sometimes on wood panel. The process would likely begin with an underdrawing to establish the composition, followed by layers of oil paint to build up form, color, and texture. Glazes – thin, transparent layers of paint – might have been used to achieve depth and luminosity, particularly in rendering the rich colors of fruit.

The meticulous detail in his work suggests the use of fine brushes and a patient, methodical application of paint. The desire to create a smooth, polished surface, where brushstrokes are often blended and minimized, was common in academic and realist painting of the 19th century, contrasting sharply with the visible, energetic brushwork that would later characterize Impressionism.

The pigments available to Forster would have been a mix of traditional earth tones and newer synthetic pigments that were becoming available throughout the 19th century. His ability to capture the vibrant hues of various fruits indicates a skillful handling of his palette and an understanding of color theory as it applied to realistic representation.

The Context of Still Life in 19th-Century America

To fully appreciate George Forster's contribution, it's helpful to understand the place of still life painting in 19th-century American culture. While landscape painting often took center stage, embodying national pride and the exploration of the continent, still life held a significant, if quieter, appeal.

Fruit and flower still lifes were popular among the burgeoning middle and upper classes. They could adorn dining rooms and parlors, serving as decorative objects that also spoke of abundance, domesticity, and the beauty of nature brought indoors. In a rapidly industrializing nation, these depictions of natural bounty could offer a sense of stability and connection to the natural world.

Furthermore, still life painting provided a vehicle for artists to demonstrate their technical prowess. The genre demanded a high level of skill in drawing, modeling, and the rendering of diverse textures. Patrons appreciated this display of artistry. While perhaps not always imbued with the overt moral or historical narratives of other genres, still lifes could carry subtle symbolic meanings related to the seasons, the cycle of life, or the vanitas theme – the fleeting nature of earthly existence.

Forster’s work, with its focus on the beauty and specificity of natural forms, participated in this broader cultural appreciation for the still life genre. His paintings would have appealed to a clientele that valued craftsmanship, realism, and the quiet charm of these intimate compositions.

Interactions and Influences

The provided information asks about George Forster's interactions with contemporary painters. For artists outside the very top tier of fame, detailed records of their social and professional networks can be difficult to reconstruct. However, artists of the period often interacted at exhibitions, through art clubs and societies, or by studying with the same masters or at the same academies.

Given that Forster exhibited at PAFA, he would have been aware of and likely encountered other Philadelphia-based artists. The art scenes in major cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and New York were relatively interconnected. While direct collaborations or documented deep friendships with specific, named painters are not readily apparent from the general historical record of Forster, he was undoubtedly part of the broader artistic conversation of his time.

His artistic influences would have stemmed from several sources. The enduring legacy of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still life painters, such as Willem Kalf or Rachel Ruysch, provided a foundational model for detailed realism and complex compositions. The work of earlier American still life painters, notably the Peale family, would also have been an important precedent. Raphaelle Peale, for instance, was known for his deceptively simple yet exquisitely rendered still lifes.

Forster would also have been aware of the prevailing academic standards of painting, which emphasized careful drawing, smooth finish, and fidelity to nature. The Düsseldorf School, with its emphasis on meticulous detail and narrative clarity, had a significant impact on many American painters in the mid-19th century, including landscape artists like Bierstadt and genre painters like Eastman Johnson. While Forster was not a landscape or primary genre painter, the general aesthetic emphasis on precision and finish from such influential schools would have permeated the artistic environment.

Later Recognition and Legacy

George Forster, like many skilled artists of his era who specialized in a particular genre, may not have achieved the posthumous fame of some of his contemporaries who broke new ground or worked on a grander scale. However, his work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of still life painting and the high level of technical skill present in American art of the 19th century.

His paintings are appreciated by collectors and connoisseurs of American still life for their meticulous execution and quiet charm. They contribute to our understanding of the artistic tastes and cultural values of the period. In the broader narrative of American art, Forster represents a dedicated practitioner of a traditional genre, upholding standards of craftsmanship and realistic representation.

The art market for 19th-century American paintings has seen periods of fluctuating interest. Artists like Forster, while perhaps not household names, are recognized within specialized circles. His works, when they appear at auction or in galleries, are valued for their historical context and artistic merit. Museums with collections of American art often seek to represent the full spectrum of artistic production, including the contributions of skilled still life painters like George Forster.

His legacy is that of a competent and dedicated artist who contributed to the richness and diversity of American art in the 19th century. While he may not have been an innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or the later trompe-l'œil masters, his commitment to his chosen genre and his ability to render the beauty of the everyday world with precision and care secure his place in the story of American still life painting. His work invites viewers to pause and appreciate the intricate details and subtle beauties of the objects he so carefully depicted.

Distinguishing Forster from Other Artists Named Forster

It is worth briefly noting, for clarity, that the art world contains other individuals named Forster, which can occasionally lead to confusion if one is not careful with dates and specializations. For example, J.W.L. Forster (John Wycliffe Lowes Forster, 1850-1938) was a well-known Canadian portrait painter, active slightly later than the American George Forster. There was also a British engraver named François Forster (1790-1872), of Swiss parentage, who was active in Paris. These are distinct individuals from the American still life painter George Forster (1817-1896). This underscores the importance of precise biographical details in art historical research.

Conclusion: Appreciating a Dedicated Craftsman

George Forster (1817-1896) stands as a fine representative of the American still life tradition in the 19th century. In an era marked by the epic landscapes of the Hudson River School and the later arrival of Impressionism, Forster dedicated himself to the intimate and meticulous art of depicting fruits, flowers, and other objects with a keen eye for detail and a skilled hand. His works, exhibited in prominent venues like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, would have appealed to contemporary tastes for realism and craftsmanship.

While not a revolutionary figure, Forster’s contribution lies in his proficient and often charming renditions of natural abundance, continuing a lineage that stretches back to European masters and was firmly established in America by artists like the Peale family. His paintings, such as the indicative "Fruit, Nuts, and a Fly," showcase a commitment to verisimilitude, inviting close observation and delighting in the textures, colors, and forms of the everyday. He worked alongside other notable still life painters such as Severin Roesen and John F. Francis, and his oeuvre provides a valuable comparison point to the later, more illusionistic trompe-l'œil works of Harnett and Peto.

Though perhaps overshadowed by artists with more dramatic narratives or groundbreaking styles like Winslow Homer or Thomas Eakins, George Forster’s art offers a quiet yet compelling glimpse into the enduring human fascination with the beauty of the tangible world. His dedication to his craft ensures his place as a noteworthy, if specialized, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century American art. His paintings remain as artifacts of a particular aesthetic sensibility and as objects of beauty in their own right.