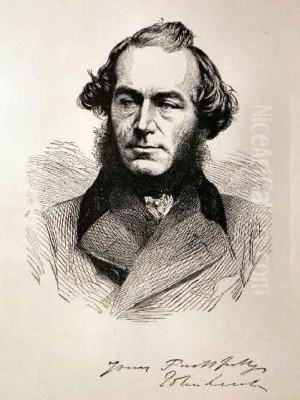

John Leech stands as a pivotal figure in the history of British illustration and caricature. Active during the heart of the Victorian era, his prolific output, particularly for the satirical magazine Punch, captured the nuances, humour, and social fabric of his time with an unmatched blend of keen observation and gentle wit. Though often overshadowed by the literary giants he illustrated, such as Charles Dickens, Leech's artistic contributions shaped the visual culture of the mid-nineteenth century and left an indelible mark on the development of graphic satire and book illustration. His work provides an invaluable window into the manners, fashions, anxieties, and aspirations of Victorian Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

John Leech was born on August 29, 1817, in Southwark, London. His father, also named John Leech, was the proprietor of the London Coffee House on Ludgate Hill—a man described as cultivated but ultimately unsuccessful in business. This background provided the young Leech with exposure to the bustling life of the city but also foreshadowed the financial insecurities that would occasionally plague the artist's own career. His innate talent for drawing manifested early; anecdotes tell of the renowned sculptor John Flaxman praising the boy's sketches when Leech was barely old enough to hold a pencil properly.

His formal education took place at Charterhouse School, a venerable institution where he formed a lasting friendship with a fellow student who would also achieve great fame: William Makepeace Thackeray. Thackeray later recalled Leech's early artistic promise, noting his constant sketching in textbooks and during lessons. Despite this evident artistic leaning, Leech's path initially led towards a more conventional profession.

Following Charterhouse, Leech enrolled at St Bartholomew's Hospital to study medicine. He demonstrated aptitude, particularly in anatomical drawing, which undoubtedly honed his observational skills and understanding of the human form. However, the financial difficulties of his father ultimately made continuing his medical education untenable. Faced with this necessity, Leech abandoned medicine around 1836 and turned his natural talent for drawing into a means of earning a living, embarking on the career that would define his life and legacy.

The Emerging Illustrator and Caricaturist

Leech's entry into the professional art world was marked by characteristic energy and a developing sense of humour. One of his earliest published works was Etchings and Sketchings by A. Pen, Esq. (1835), a collection of humorous character studies of London street life. This modest publication already hinted at his knack for capturing social types and everyday absurdities. He continued to produce various humorous sketches, political cartoons, and illustrations for periodicals and books.

During these formative years, Leech inevitably worked within the shadow of established giants of graphic satire. The ferocious political commentary of James Gillray and the boisterous social scenes of Thomas Rowlandson had defined the preceding era. A more immediate influence and contemporary was the immensely popular George Cruikshank, whose detailed and often grotesque style dominated book illustration and caricature in the 1830s. Leech learned from these predecessors, particularly Cruikshank, but gradually began to forge his own distinct style.

He contributed illustrations to various publications, including Bell's Life in London and several magazines. He also illustrated books such as Richard Harris Barham's The Ingoldsby Legends and produced his own comic works like the Comic English Grammar (1840) and Comic Latin Grammar (1840). These projects helped him refine his technique, particularly in etching and, increasingly, wood engraving, which was becoming the dominant medium for periodical illustration due to its compatibility with letterpress printing.

The Cornerstone of Punch

The founding of Punch, or The London Charivari in 1841 proved to be the defining moment of John Leech's career. He joined the staff shortly after its inception, reportedly introduced by his old schoolfellow Thackeray, and quickly became one of its most important and prolific contributors. For over two decades, until his death in 1864, Leech was the backbone of Punch's visual identity. His work appeared in nearly every issue, cementing the magazine's reputation for witty social commentary and gentle political satire.

His contribution was immense. It is estimated that he produced over 3,000 drawings for Punch, including countless smaller "social cuts" observing everyday life and manners, as well as around 600 larger, more formal political cartoons, often referred to as the "big cut." He became a fixture at the famous Punch Table, the weekly dinner meeting where the magazine's writers and artists discussed current events and planned the content for the next issue. Here, he collaborated and debated with figures like the editor Mark Lemon, writers Douglas Jerrold and Thackeray himself, and fellow artists like Richard Doyle, and later, John Tenniel.

Leech's work for Punch covered the entire spectrum of Victorian life. He depicted the foibles of fashion, the rise of the middle classes, the pleasures and perils of new technologies like the railway, sporting pursuits (especially fox hunting, a personal passion), seaside holidays, domestic dramas, and the interactions between different social strata. His political cartoons addressed major events, from the Corn Laws and the Irish Famine to the Crimean War and the rise of Napoleon III, often embodying national sentiment through figures like John Bull, whom he frequently drew (sometimes in collaboration or alternation with Tenniel).

Artistic Style: Humour, Realism, and Gentility

John Leech's style marked a significant departure from the often savage and grotesque caricature of the Gillray and Rowlandson era. While influenced by Cruikshank, Leech developed a manner that was generally gentler, more observational, and arguably more aligned with the sensibilities of the rising Victorian middle class. His humour stemmed less from exaggerated distortion and more from the accurate, slightly amplified depiction of recognisable social types and situations.

His draughtsmanship was characterised by a fluid, confident line. He had an exceptional ability to capture expression and gesture with apparent ease, conveying character and narrative succinctly. While trained in etching, the demands of Punch meant most of his work was designed for wood engraving. He would draw directly onto the woodblock or transfer his drawing, which would then be engraved by skilled artisans like Joseph Swain. This process required clarity and precision in the original drawing.

Leech worked comfortably across different modes. His social sketches often employed a light, almost conversational realism, capturing the details of dress, furniture, and setting that grounded his scenes in contemporary life. Yet, particularly in his illustrations for ghost stories or more dramatic moments, he could incorporate elements of Romanticism, using shadow and atmosphere effectively. He was also a capable watercolourist, sometimes exhibiting finished watercolours based on his Punch drawings or creating independent works. His use of colour, especially in his hand-coloured etchings for books, was often lively and appealing.

His satire, while pointed, rarely reached the level of bitterness found in earlier caricaturists. He poked fun at social climbers, pretentious aesthetes, henpecked husbands, and mischievous children, but often with an underlying sympathy or amusement rather than outright condemnation. His political cartoons could be critical, but they often reflected a mainstream, patriotic viewpoint, sometimes embodying contemporary prejudices, such as stereotypical depictions of Irish or Jewish people, or a jingoistic stance during wartime.

Illustrating Dickens and the Literary World

One of John Leech's most enduring legacies lies in his collaboration with Charles Dickens, particularly his illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843). Dickens specifically requested Leech, alongside other artists initially considered, but Leech ultimately became the sole illustrator for this iconic novella, providing four hand-coloured etchings and four black-and-white wood engravings. These images—Scrooge visited by Marley's Ghost, the Fezziwigs' ball, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the final poignant image of Ignorance and Want—became instantly inseparable from the text.

Leech's illustrations perfectly captured the blend of ghostly atmosphere, festive cheer, and sharp social commentary in Dickens's story. His depiction of Scrooge, the ghosts, and the Cratchit family profoundly influenced subsequent visual interpretations and contributed significantly to the book's immediate and lasting success. The speed at which the book was produced meant Leech worked under intense pressure, but the result was a triumph of collaborative synergy between author and artist.

Following this success, Leech illustrated several other Christmas Books by Dickens, including The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), and The Battle of Life (1846), although often alongside other artists like Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. His relationship with Dickens was generally cordial, built on mutual respect, though Leech sometimes felt overshadowed or inadequately compensated compared to the author's immense fame and earnings.

Beyond Dickens, Leech was a sought-after illustrator for various authors and genres. He provided memorable illustrations for the sporting novels of Robert Smith Surtees, such as Mr. Sponge's Sporting Tour and Handley Cross, where his love for equestrian scenes found full expression. He also illustrated Gilbert Abbott à Beckett's Comic History of England (1847-48) and Comic History of Rome (1851), bringing a lighthearted, anachronistic humour to historical events. These diverse commissions showcased his versatility and cemented his reputation as a leading illustrator of his day, working alongside other prominent figures in the field like Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), Dickens's primary illustrator for his longer novels.

Chronicling Society: Key Works and Themes

While his book illustrations reached a wide audience, Leech's most consistent and perhaps most significant contribution was his weekly work for Punch. Many of his drawings from the magazine were later collected and republished in popular volumes, most notably the series Pictures of Life and Character (1854–1869), which ran to five volumes and offered a panoramic view of mid-Victorian society as seen through Leech's eyes. These collections became staples in middle-class homes, preserving Leech's observations for posterity.

His themes were drawn directly from the world around him. He excelled at depicting the nuances of social class, from the hauteur of the aristocracy and the aspirations of the bourgeoisie to the perceived deference or occasional insolence of domestic servants. The "servant problem," the challenges of managing household staff, was a recurring topic. Fashion was another favourite subject, with Leech gently mocking the extremes of crinolines, elaborate bonnets, and the changing styles of menswear.

Leech captured the leisure activities of the Victorians: the hunting field, the seaside resort (with its bathing machines and promenades), the croquet lawn, the dinner party, the ballroom. He documented the impact of new technologies, particularly the railways, showing the bustle of stations, the discomforts of travel, and the way trains were changing the landscape and social habits. Children featured prominently, often depicted with an unsentimental eye for their mischief and wilfulness – his "urchins" were a popular recurring motif.

His political cartoons, the "big cuts" in Punch, addressed the major issues of the day. He depicted key political figures like Lord Palmerston, Lord John Russell, Benjamin Disraeli, and foreign leaders like Napoleon III and Tsar Nicholas I. His cartoons during the Crimean War (1853-1856) often reflected patriotic fervour but also sometimes hinted at the mismanagement and suffering involved, contributing to the complex public perception of the conflict. Works like "Substance and Shadow" (1843), criticizing the government's priorities, showed his capacity for sharp political commentary.

Contemporaries and Artistic Circle

John Leech moved within a vibrant circle of artists, writers, and intellectuals in mid-Victorian London. His closest professional ties were undoubtedly with his colleagues at Punch, including Thackeray, Mark Lemon, Douglas Jerrold, Shirley Brooks, and fellow artists Richard Doyle and John Tenniel. The camaraderie and creative exchange fostered by the Punch Table were crucial to his work. His relationship with Thackeray was particularly long-standing, dating back to their schooldays at Charterhouse.

His collaboration with Charles Dickens placed him at the heart of the literary world. He was also acquainted with other prominent illustrators of the day, such as George Cruikshank, whose work he initially emulated, and Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), though their styles differed significantly. Leech's focus on contemporary manners and gentle satire contrasted with Phiz's more intricate and often darker style used in Dickens's serial novels.

Leech also knew painters outside the immediate circle of illustration. He was friends with the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais, who reportedly admired Leech's draughtsmanship. Through Millais, he likely encountered other figures in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, although Leech's own artistic aims remained distinct from their more aesthetic and medievalizing concerns. He was also a contemporary of William Powell Frith, whose large-scale narrative paintings like Derby Day and The Railway Station offered a more detailed, panoramic, and perhaps less satirical vision of Victorian life, yet shared Leech's interest in observing social types and contemporary scenes.

Social Commentary and Cultural Impact

John Leech was more than just a humorous artist; he was a social commentator whose work both reflected and subtly shaped the attitudes of his time. Through the widely circulated pages of Punch, his drawings reached a vast middle-class audience, reinforcing certain social norms while gently critiquing others. His consistent depiction of everyday life helped to create a shared visual understanding of what it meant to be Victorian.

His work often highlighted class distinctions, sometimes sympathetically, sometimes playing on stereotypes. His portrayal of the aspirational middle classes, navigating the complexities of social etiquette and domestic management, resonated strongly with his readership. While generally avoiding the fierce political partisanship of earlier caricaturists, his cartoons nonetheless contributed to public discourse on issues ranging from public health and poverty (as seen in A Christmas Carol) to foreign policy and military campaigns.

His influence extended to the very definition of "cartoon." While the term originally referred to a preparatory drawing for a larger work (like the Raphael Cartoons), Punch began satirically applying the term to its political drawings in the 1840s, partly inspired by overly grand designs submitted for frescoes in the new Houses of Parliament. Leech's prominent political drawings helped solidify this new meaning of "cartoon" as a humorous or satirical illustration commenting on current events.

Furthermore, Leech's accessible and often charming style played a role in making illustration and caricature more respectable and acceptable in polite society. His work demonstrated that graphic art could be witty and observant without necessarily being vulgar or aggressively partisan, paving the way for later generations of illustrators and cartoonists.

Later Years, Recognition, and Declining Health

By the late 1850s and early 1860s, John Leech was at the height of his fame and productivity. His Punch drawings were immensely popular, and the collected volumes of Pictures of Life and Character sold extremely well. Seeking to capitalize further on his success and perhaps alleviate persistent financial pressures, he devised a new exhibition format.

In 1862, he opened an exhibition at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly titled "John Leech's Sketches in Oil." For this show, he developed a novel technique: enlarging a selection of his Punch drawings using a magic lantern, tracing the outlines onto large canvases, and then colouring them in oils. While not sophisticated oil paintings in the traditional sense, these large, colourful versions of his familiar sketches proved enormously popular with the public. The exhibition was a critical and financial success, attracting thousands of visitors and providing Leech with a much-needed financial boost.

Despite this success, the relentless demands of his weekly contributions to Punch, combined with other commissions and the stress of organizing his exhibition, took a toll on his health. Leech suffered from nervousness and an increasing sensitivity to noise, particularly street sounds like organ grinders, which plagued him at his home in Kensington. Friends noted his growing exhaustion and anxiety. He was diagnosed with angina pectoris, a heart condition likely exacerbated by overwork and stress.

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

John Leech died suddenly from an angina attack on October 29, 1864, at his home, 6 The Terrace, Kensington. He was only 47 years old. His premature death shocked his friends, colleagues, and the reading public, who had come to regard him as a national institution. He was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London, mourned by many from the artistic and literary worlds.

His legacy was immediate and profound. He had defined the visual humour of Punch for over two decades, creating a style of social observation and gentle satire that would influence the magazine for decades to come. Artists like George du Maurier and Charles Keene, who were already contributing to Punch, carried on the tradition of social cartooning, though each developed their own distinct styles. John Tenniel continued as the primary political cartoonist, solidifying the more formal, classical style he had established.

Leech's influence extended far beyond Punch. His approach to book illustration, particularly his successful collaboration with Dickens on A Christmas Carol, highlighted the power of images to enhance and interpret literature, influencing later great illustrators like Arthur Rackham, who also excelled at capturing atmosphere and character. His keen observation of social types and manners provided a template for countless humorous artists and social commentators in graphic media.

More broadly, John Leech's work remains an invaluable historical resource. His thousands of drawings offer a detailed, witty, and often intimate glimpse into the daily life, social structures, and cultural preoccupations of mid-Victorian Britain. He captured a society in transition, grappling with industrialization, urbanization, and evolving social norms. While reflecting some of the biases of his era, his art primarily conveys a sense of shared humanity, finding humour and pathos in the everyday experiences of ordinary and extraordinary Victorians. He was, as Thackeray suggested, a kind and gentle satirist, a keen observer whose pencil chronicled an age.

Conclusion

John Leech's career, though tragically cut short, represents a high point in British graphic art. As a cornerstone of Punch magazine, a sensitive illustrator of literature, and a sharp observer of Victorian society, he created a body of work remarkable for its volume, consistency, and enduring charm. His ability to blend humour with realism, and satire with a degree of empathy, set him apart from many predecessors and contemporaries. He not only documented his times but helped define their visual identity, leaving a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of the Victorian era and the enduring power of caricature and illustration.