George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923) stands as one of the most significant figures in Dutch art history, a powerful painter and pioneering photographer whose work vividly captured the energy, grit, and atmosphere of Amsterdam during a period of rapid transformation. Bridging the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Breitner became the foremost exponent of Amsterdam Impressionism, developing a distinctively Dutch take on modern art that focused on the realities of urban life. Known affectionately and accurately as "the painter of the people," his canvases pulse with the life of the city's streets, canals, and working-class inhabitants, rendered in a bold, dynamic style that continues to resonate today. His legacy is twofold, encompassing both his influential paintings and his remarkably candid photographic archive, which together provide an unparalleled portrait of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

George Hendrik Breitner was born in Rotterdam on September 12, 1857. His initial artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Royal Academy of Art in The Hague (Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten) in 1876. However, Breitner's temperament and artistic vision soon clashed with the institution's academic constraints. He found the emphasis on traditional techniques and historical subjects stifling, yearning for a more direct engagement with contemporary life.

His rebellious spirit and dissatisfaction with the curriculum led to his expulsion from the Academy in 1880 for "misconduct." This event, while seemingly a setback, proved pivotal. It freed Breitner to pursue his own path, one less concerned with academic approval and more focused on observing and depicting the world around him with unflinching honesty. Even during his academy years, he showed a preference for realism, a tendency that would define his mature work.

Following his departure from the Academy, Breitner remained in The Hague for a period, immersing himself in the city's vibrant artistic scene. This was a crucial formative time, where he began to forge connections and refine his skills outside the formal academic structure. His experiences in The Hague laid the groundwork for his later move to Amsterdam, the city that would become his ultimate muse.

The Hague Years: Hague School Connections and Van Gogh

During his time in The Hague, Breitner inevitably came into contact with the Hague School (Haagse School), the dominant movement in Dutch painting at the time. This group of artists, including figures like Jozef Israëls, Jacob Maris, Willem Maris, and Anton Mauve, favored realistic depictions of Dutch landscapes, peasant life, and coastal scenes, often rendered in muted, atmospheric tones.

Breitner initially associated with members of the Hague School. He worked for a time in the studio of Willem Maris, known for his luminous landscapes with cattle, and collaborated on panoramas, a popular form of large-scale painting at the time. He participated in the creation of the Panorama Mesdag, working alongside Hendrik Willem Mesdag himself. These experiences honed his technical skills, particularly in capturing light and atmosphere, hallmarks of the Hague School style.

However, Breitner's focus began to shift away from the rural and coastal subjects favored by the Hague School towards more urban and figural themes. A significant, albeit complex, relationship during this period was with Vincent van Gogh. Between 1882 and 1883, Breitner and Van Gogh frequently sketched together in the working-class districts of The Hague, sharing an interest in depicting the lives of the poor and marginalized. Both artists were drawn to the raw authenticity of these subjects. Despite this shared early interest, their paths diverged significantly, both artistically and personally. Breitner later became quite critical of Van Gogh's post-Impressionist work, famously remarking that he found it "art for Eskimos," unable to appreciate its radical departure from realism.

Amsterdam: The Urban Muse

In 1886, George Hendrik Breitner made the decisive move to Amsterdam. This relocation marked the beginning of the most productive and defining phase of his career. Amsterdam, then undergoing significant growth and industrialization, provided Breitner with an inexhaustible source of inspiration. He was captivated by the city's dynamic energy, its bustling streets, its ever-changing skyline, and the lives of its inhabitants.

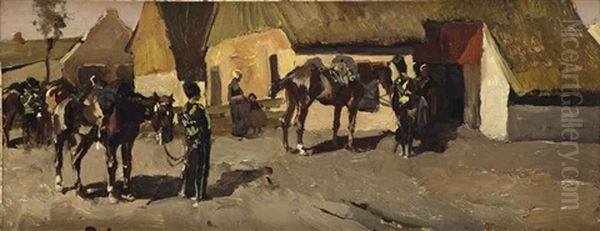

Unlike the Hague School artists who often sought tranquility in nature, Breitner embraced the chaos and vitality of the modern metropolis. He prowled the city with his sketchbook and, later, his camera, drawn to scenes that reflected Amsterdam's transformation: construction sites where old neighborhoods were demolished to make way for new developments, the busy canals filled with barges, the newly laid tram lines, the elegant cavalry parades, and the powerful draft horses pulling carts through the streets.

Breitner had a particular fascination with the city's atmosphere, especially under inclement weather conditions. He became renowned for his depictions of Amsterdam in the rain, snow, or twilight. He masterfully captured the reflections on wet pavements, the hazy silhouettes of buildings in the fog, and the stark beauty of the city under a blanket of snow. The canals, bridges, and narrow streets of Amsterdam became the stage upon which Breitner documented the relentless pulse of urban existence.

Amsterdam Impressionism: A Dutch Vision

Breitner quickly became the leading figure of Amsterdam Impressionism, a movement that emerged in the late 19th century as a distinct counterpoint to the more established Hague School. While sharing the Impressionist interest in capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light, Amsterdam Impressionism differed significantly from its French counterpart.

Where French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir often favored brighter palettes and scenes of leisure, Breitner and his Amsterdam contemporaries, such as Isaac Israëls, embraced a darker, more somber range of colors – rich browns, deep greys, and blacks, punctuated by flashes of light. Their subject matter was resolutely urban and often focused on the less glamorous aspects of city life: labor, movement, and the raw energy of the streets.

Breitner's style was characterized by vigorous, often broad brushstrokes, creating textured surfaces that conveyed the immediacy and dynamism of the scene. He wasn't interested in precise detail but rather in capturing the overall impression, the mood, and the movement. His compositions often feel spontaneous, sometimes employing cropping techniques reminiscent of photography, cutting figures off at the edge of the canvas to enhance the sense of a captured moment in time. Isaac Israëls, often seen as Breitner's friendly rival, shared this interest in Amsterdam's street life, though his touch was generally lighter and his palette sometimes brighter than Breitner's more robust approach. Willem Witsen, another key figure, contributed with his more melancholic and atmospheric etchings and paintings of the city.

"Le Peintre du Peuple": Chronicler of the Working Class

Breitner earned the moniker "Le peintre du peuple" – the painter of the people – for his consistent focus on the ordinary inhabitants of Amsterdam. He turned his gaze away from the bourgeoisie and towards the working class: maids scrubbing steps, laborers on construction sites, coachmen waiting in the rain, women navigating crowded streets, dockworkers hauling cargo. He depicted them not with sentimentality, but with a direct, unsentimental realism that acknowledged their presence and vitality within the urban fabric.

This commitment to depicting everyday life aligns Breitner with the broader Realist tradition exemplified by French artists like Gustave Courbet, who famously declared he would paint only what he could see. Like Courbet, Breitner rejected idealized or historical subjects in favor of the tangible reality of his own time. His work also resonates with the social observation found in the art of Honoré Daumier or Jean-François Millet, though Breitner's focus remained firmly on the urban environment rather than rural peasant life.

His paintings of servant girls, often depicted in moments of quiet labor or contemplation, are particularly notable. These works avoid condescension, instead portraying these women with dignity and a sense of individual presence. Breitner saw the streets and homes of Amsterdam as populated by real people, each contributing to the city's complex character, and he sought to capture that reality on canvas.

The Controversial Nudes and Japonisme

Beyond his celebrated cityscapes, Breitner also produced a significant body of work depicting female nudes, which proved controversial in his time. Unlike the idealized, mythological, or allegorical nudes common in academic art (as produced by artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau), Breitner's nudes were strikingly realistic and often set in contemporary domestic interiors. They were unidealized, depicting real women with a directness that some critics found shocking or lacking in conventional beauty.

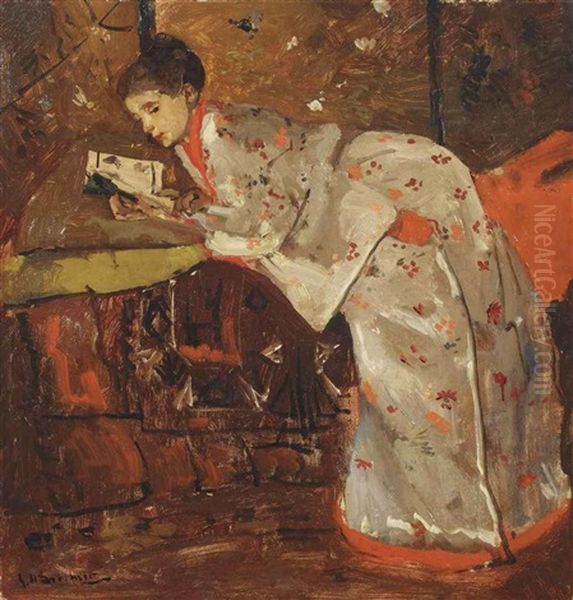

His most famous series in this genre features young women, notably his model Geesje Kwak, dressed in kimonos. These paintings, such as the renowned Girl in a White Kimono (c. 1894), reflect the widespread influence of Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics – that swept through artistic circles in the late 19th century. Artists like James McNeill Whistler had also explored similar themes.

In Breitner's kimono paintings, the decorative patterns of the fabric and the intimate, often dimly lit interiors create a different mood from his bustling street scenes. Yet, the underlying realism remains. The figures are portrayed with psychological depth, sometimes appearing vulnerable, sometimes lost in thought. The controversy surrounding these works stemmed from their perceived departure from accepted norms of depicting the female form, challenging the prevailing aesthetic ideals with their frankness and modernity.

Breitner the Photographer: A Second Lens on Amsterdam

Parallel to his painting career, Breitner was an avid and pioneering photographer. He embraced the camera not just as a hobby but as an integral part of his artistic process, particularly from the late 1880s onwards. He used photography extensively to capture fleeting moments, study compositions, record atmospheric effects, and document the urban scenes that fascinated him.

Breitner's photographs often served as direct source material or aides-mémoires for his paintings. He captured moving horses, pedestrians caught mid-stride, and the specific light conditions of rainy or snowy days – elements difficult to sketch quickly on the spot. His photographic eye mirrored his painterly one, focusing on dynamic street life, unusual angles, and the raw texture of the city. He experimented with the 'snapshot' aesthetic long before it became widely accepted, capturing candid moments with an immediacy that was revolutionary for the time.

For many years, Breitner's photographic work remained largely unknown. It wasn't until decades after his death that the full extent of his photographic archive – thousands of negatives and prints – came to light. This discovery revealed him to be one of the most important Dutch photographers of his era. His photographs are now valued not only for their connection to his paintings but also as significant historical documents in their own right, offering a unique and unfiltered glimpse into Amsterdam at the turn of the century. His use of photography as a tool connects him to other modern artists like Edgar Degas, who also explored the camera's potential.

Style and Technique: Capturing Urban Energy

Breitner's artistic style is immediately recognizable for its energy and tactile quality. His brushwork is typically bold, vigorous, and expressive, often applied in thick layers (impasto) that give the canvas surface a distinct texture. He wasn't afraid to leave brushstrokes visible, contributing to the sense of dynamism and immediacy in his work. This technique allowed him to convey the rough surfaces of brick walls, the wetness of streets, or the texture of heavy fabrics.

His palette, particularly in his cityscapes, tended towards darker, more somber tones compared to the French Impressionists. He masterfully employed browns, greys, ochres, and blacks to capture the often overcast skies and gritty atmosphere of Amsterdam. However, he skillfully used contrasts of light and shadow to create drama and focus attention. Streetlights reflecting on wet cobblestones, the illuminated windows of buildings at dusk, or the stark white of snow against dark architecture are recurring motifs.

Compositionally, Breitner often favored dynamic arrangements. Diagonal lines created by streets or bridges frequently lead the viewer's eye into the scene. He embraced asymmetrical compositions and sometimes used cropping inspired by photography, cutting figures or architectural elements at the edges of the frame. This technique enhances the feeling of a captured moment, a slice of ongoing life rather than a formally staged scene. His ability to render atmosphere – the damp chill of rain, the muffled silence of snow, the hazy glow of twilight – remains one of the most compelling aspects of his work.

Analysis of Representative Works

Breitner's oeuvre is rich with iconic depictions of Amsterdam. Examining a few key works reveals the core elements of his style and vision:

_The Singel Bridge at the Paleisstraat in Amsterdam_ (1896, reworked 1898): This painting is perhaps Breitner's most famous snow scene. It depicts a lone woman with an umbrella walking across the bridge towards the viewer, while the city behind her is muffled by falling snow. The brushwork is energetic, capturing the movement of the figure and the swirling snow. The palette is dominated by whites, greys, and browns, perfectly evoking the cold, damp atmosphere of a winter day in Amsterdam. The composition, with the strong diagonal of the bridge and the centrally placed figure, creates a sense of both dynamism and urban solitude.

_Girl in a White Kimono_ (c. 1894): Part of the celebrated series featuring Geesje Kwak, this painting showcases a different facet of Breitner's art. The setting is intimate, likely Breitner's studio. The young woman reclines on a divan, draped in a white kimono adorned with red floral patterns. The influence of Japonisme is evident in the subject matter and the decorative elements. While the setting is different from his street scenes, Breitner's realistic approach persists in the unidealized portrayal of the model and the tangible rendering of textures – the soft fabric, the wooden floor, the patterned rug. The mood is contemplative and slightly melancholic.

_The Damrak in Amsterdam_ (various versions, e.g., 1903): Breitner painted the Damrak, a major waterway and street in the heart of Amsterdam, multiple times. These works often depict the bustling activity of the area, with barges moored along the canal, horse-drawn carts on the street, and the imposing architecture of the city rising in the background. He captures the reflections in the water and the interplay of light and shadow on the buildings, conveying the commercial energy of this central artery. The robust brushwork and often somber tones emphasize the working character of the port city. Other notable works include The Rokin in Amsterdam (1897) and De Dam (1891), capturing different facets of the city's life.

Later Career, Recognition, and Challenges

By the turn of the 20th century, Breitner was a well-established and highly regarded figure in the Dutch art world. His solo retrospective exhibition at the Arti et Amicitia society in Amsterdam in 1901 was a major success, cementing his reputation as one of the country's leading painters. His work was admired by fellow artists and collectors alike for its power and authenticity.

Despite his artistic success, Breitner reportedly faced periods of financial difficulty throughout his life. Furthermore, while celebrated, his uncompromising realism and sometimes dark subject matter continued to draw criticism from more conservative quarters of the Dutch art establishment, particularly regarding his nudes.

As the early 20th century progressed, new avant-garde movements began to emerge across Europe, such as Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. While Breitner remained committed to his own distinctive style of realism and Impressionism, the art world's focus began to shift. Younger artists, including Dutch modernists like Piet Mondrian (who himself started with landscape painting influenced by the Hague School and Impressionism before moving towards abstraction), were exploring radically new forms of expression. While Breitner's influence was undeniable, his style eventually came to be seen by some as belonging to a previous era, even as his reputation as a master remained secure.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

George Hendrik Breitner's impact on Dutch art is profound and lasting. He decisively shifted the focus of Dutch painting from the rural preoccupations of the Hague School to the dynamism of modern urban life. He, along with Isaac Israëls, defined Amsterdam Impressionism and created an enduring visual record of the Dutch capital during a pivotal period of its history.

His bold technique and realistic vision influenced subsequent generations of Dutch artists. Even artists who moved in different directions, like Henri Matisse who admired his work, acknowledged the power of his painting. Breitner demonstrated that everyday urban scenes and working-class life were valid and compelling subjects for serious art, paving the way for later forms of social realism in the Netherlands. He holds a place in Dutch art history comparable to major figures like Jozef Israëls or even international contemporaries like Courbet and Manet in terms of his impact on national art.

Beyond his paintings, the rediscovery and appreciation of his extensive photographic work in the latter half of the 20th century added another dimension to his legacy. His photographs are now recognized as a crucial contribution to early Dutch photography and provide invaluable insights into his working methods and his perception of the city. Today, Breitner is celebrated as a master painter and a pioneering photographer, a dual talent who captured the soul of Amsterdam with unparalleled intensity.

Collections and Exhibitions

George Hendrik Breitner's works are prominently featured in major Dutch museums, testifying to his enduring importance. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam holds a significant collection, including key works like The Singel Bridge at the Paleisstraat in Amsterdam and The Damrak in Amsterdam. The museum has also hosted major thematic exhibitions, such as "Breitner: Girl in Kimono," exploring specific aspects of his oeuvre.

Other important public collections housing Breitner's paintings and photographs include the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the Van Gogh Museum (acknowledging his connection to Vincent), the Kunstmuseum Den Haag (formerly Gemeentemuseum, which held a major retrospective during his lifetime and holds works like De Dam), the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, the Drents Museum in Assen (Woman on an Acre), and the Museum Twente in Enschede. His works also appear in numerous private collections and are sought after on the art market, frequently appearing at auction houses like Sotheby's and AAG Auctioneers. Numerous exhibitions, both in the Netherlands and internationally, continue to explore his work, reaffirming his status as a major figure in European art.

Conclusion: The Eye of Amsterdam

George Hendrik Breitner remains a towering figure in Dutch art, the quintessential painter of Amsterdam at the turn of the 20th century. Through his powerful brushwork, his keen eye for detail, and his deep empathy for the city and its people, he created a body of work that transcends mere documentation. His paintings capture the energy, the atmosphere, the grit, and the fleeting beauty of modern urban life. As the leading force behind Amsterdam Impressionism, he forged a distinctly Dutch path within the broader currents of modern European art. His dual role as a master painter and a pioneering photographer provides a uniquely rich and comprehensive vision of his time. Breitner did more than just paint Amsterdam; he captured its very pulse, leaving behind a legacy that continues to fascinate and inspire.