Edgar Degas (1834–1917) stands as a titan of 19th-century French art, a figure who, while often associated with the Impressionists, carved out a unique and enduring legacy as a "realist" observer of modern life. Born into a wealthy Parisian family, Degas's journey from a privileged upbringing to a master artist is a fascinating study in dedication, innovation, and the complexities of human nature. His keen eye for capturing movement, his unconventional compositions, and his exploration of diverse subjects like ballet dancers, racehorses, and the mundane routines of working women set him apart and continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Family Influence

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas was born on July 19, 1834, in Paris. His father, Auguste De Gas, was a banker of Italian descent, and his mother, Célestine Musson, hailed from New Orleans. This transatlantic family background, with roots stretching to a Creole grandfather in Haiti and cotton merchant relatives in New Orleans, imbued Degas with a unique perspective. While his family harbored a touch of aristocratic pretension, even briefly altering their surname to "De Gas" for an air of grandeur, they provided Edgar with a solid foundation.

He received a rigorous education, attending the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand from 1845 to 1852, where he graduated with a baccalauréat in literature in 1853. Although his father initially envisioned a legal career for him, Degas's passion for art was undeniable and ultimately prevailed. Fortunately, his parents supported his artistic aspirations, allowing him to establish a studio in their home, a space that became crucial to his early development.

A significant turning point in Degas's personal life was the death of his mother when he was just 13. This loss had a profound emotional impact and is believed to have influenced his artistic output. His mother, Célestine Musson, came from a musical family and was an amateur opera singer. His father also fostered a love for music, frequently hosting concerts at their home. This vibrant cultural environment undoubtedly nurtured Degas's burgeoning artistic sensibilities. His connections to the Musson family in New Orleans also proved influential; his visits to his uncle, Michel Musson, a cotton merchant, exposed him to different facets of life and provided fresh inspiration for his work.

Artistic Training and Evolution

Degas's artistic journey began with a deep immersion in classical art. He spent countless hours at the Louvre, meticulously copying the works of old masters, a practice that laid the groundwork for his exceptional technical skill. He also traveled to Italy, where he furthered his studies in painting and sculpture, absorbing the lessons of the Renaissance masters.

His early works reflected this traditional training, primarily focusing on historical paintings and portraits. However, as he matured as an artist, Degas shifted his focus to depicting modern life, a move that aligned him with the burgeoning Impressionist movement. He became fascinated with capturing the fleeting moments and dynamic energy of the contemporary world, finding endless inspiration in subjects like ballet dancers, horse racing, and female nudes.

Degas's style was a compelling blend of traditional techniques and innovative approaches. He was a master of drawing, utilizing pencil, charcoal, and pastels for his sketches, which often served as the foundation for his finished works. In his later years, he explored more abstract forms in both painting and sculpture, demonstrating a continuous evolution in his artistic vision. While he was closely associated with Impressionist painters like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, he maintained a distinct artistic identity. He notably refused to participate in the official Impressionist exhibitions, instead co-founding the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers) with artists such as Sisley and Édouard Manet, providing a platform to showcase modern, often urban, subjects, including representations of modern women.

Key Themes and Subjects

Degas is perhaps best known for his captivating depictions of ballet dancers. He spent countless hours observing them in rehearsal and performance, capturing their grace, discipline, and the often-overlooked moments of exhaustion and preparation. Works like The Dance Class (1874) are iconic examples of this obsession, showcasing the dancers' postures and the harmonious interaction between the figures and the studio environment. These paintings are not idealized portrayals but rather insightful glimpses into the reality of a dancer's life, capturing both the beauty and the physical demands of their profession.

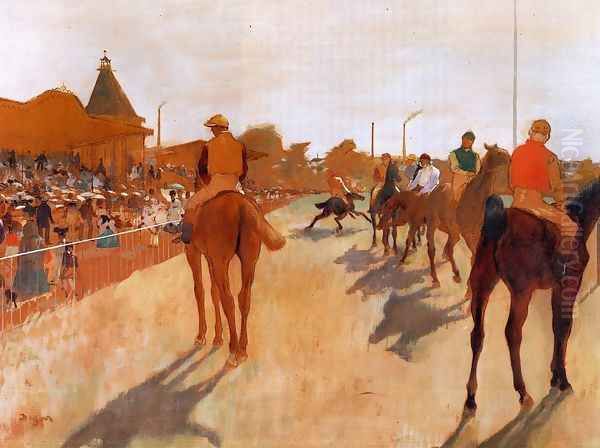

Horse racing was another subject that captivated Degas. He was drawn to the speed, power, and dynamism of the horses and jockeys, translating these qualities onto canvas and paper with remarkable skill. His racehorse paintings, such as Racehorses (1865-1866), are characterized by their unconventional compositions and their ability to convey a sense of motion and excitement.

Degas also turned his gaze to the lives of ordinary people in Paris. He depicted laundresses, milliners, and cafe-goers, offering intimate glimpses into their daily routines and social interactions. The Ironing Woman (1873) is a notable example, highlighting the labor and quiet dignity of working-class women. These works demonstrated his commitment to realism and his interest in documenting the realities of modern urban life.

His depictions of female nudes, often shown in private moments of bathing or grooming, were both celebrated and controversial. While some admired his ability to capture the naturalness and physicality of the female form, others found these works to be voyeuristic or lacking in idealized beauty. The Tub (1886) exemplifies this aspect of his work, utilizing soft colors and delicate brushstrokes to convey a sense of intimacy and tranquility.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Degas's artistic style is characterized by its fusion of Impressionist principles with a strong grounding in academic drawing and composition. While he shared the Impressionists' interest in capturing light and movement, he often worked from memory or sketches rather than painting en plein air. His compositions were often daring and innovative, employing unusual angles, cropped figures, and asymmetrical arrangements, influenced by Japanese prints and the burgeoning art of photography. This approach lent his works a sense of immediacy and spontaneity, as if capturing a fleeting moment in time.

He was a master of various mediums, moving seamlessly between oil paint, pastel, watercolor, etching, and sculpture. His use of pastel, in particular, allowed him to achieve vibrant colors and nuanced textures, giving his works a luminous quality. In his later years, as his eyesight deteriorated, he increasingly turned to sculpture, creating a remarkable body of work, primarily in wax, which captured the dynamism and fluidity of his favored subjects, particularly dancers. The bronze casts of these wax sculptures, like Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, are now among his most celebrated works.

Relationship with Impressionism and Legacy

Despite his close association with the Impressionists and his participation in several of their exhibitions, Degas was a fiercely independent artist who resisted strict categorization. He preferred the term "realist" to describe his approach, emphasizing his commitment to depicting the world as he saw it, without idealization. His focus on indoor scenes, artificial light, and the human figure also differentiated him from core Impressionists who often focused on landscapes and the effects of natural light.

Nonetheless, his innovative compositions, his interest in modern life, and his exploration of light and movement undeniably contributed to the Impressionist movement and the broader shift towards modern art. He was a figure of immense influence, admired by younger generations of artists, including post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh, as well as later masters like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. His impact can be seen in their explorations of form, color, and the representation of modern subjects.

Degas's legacy extends beyond his paintings and sculptures. He was also a skilled printmaker and a pioneering photographer, exploring the potential of these mediums to capture movement and form. His extensive collection of artworks, including Japanese woodblock prints and works by Italian Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, as well as works by his contemporaries like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix, further reveals his artistic interests and influences.

Personal Life and Controversies

Degas was a complex and often contradictory figure. He remained unmarried throughout his life and was known for his solitary and somewhat withdrawn nature, particularly in his later years. He was a keen observer of human behavior, often described as having a sharp wit and a sometimes caustic tongue. While he could be a loyal friend, his personality could also be challenging, leading to strained relationships.

A significant and unfortunate controversy in Degas's life was his embrace of anti-Semitism in his later years, particularly during the Dreyfus Affair. This stance led to the alienation of several of his close Jewish friends, including the prominent art critic and collector Ludovic Halévy, a close friend and collaborator. This aspect of his life remains a troubling stain on his legacy and contributed to his increasing isolation.

Despite his personal foibles and the controversies that surrounded him, Degas's dedication to his art was unwavering. He continued to work tirelessly, even as his eyesight failed him, adapting his techniques and exploring new mediums to continue his creative pursuits.

Later Years and Death

In his later years, Degas’s eyesight began to seriously decline, making detailed work increasingly difficult. He turned more to pastel and sculpture, mediums that allowed for a more tactile and less visually demanding approach. Despite the challenges, he continued to produce powerful and expressive works. His sculptures, often spontaneous studies in wax, captured the essence of movement with remarkable vitality.

Edgar Degas died on September 27, 1917, at the age of 83. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His death marked the end of an era, but his artistic legacy continued to grow.

Enduring Significance

Edgar Degas remains one of the most important and influential artists of the 19th century. His ability to capture the essence of modern life, his innovative compositions, and his mastery of various mediums have secured his place in art history. His works are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Gallery in London, testament to their enduring appeal and significance.

Degas’s art offers a compelling window into the social and cultural landscape of late 19th-century Paris. He was a keen observer of human nature, depicting both the public spectacle of the ballet and the race track, and the private moments of individuals. His work transcends simple representation, delving into the psychology and physicality of his subjects.

While the controversies of his personal life cannot be ignored, they do not diminish the brilliance and impact of his artistic output. Edgar Degas was a revolutionary artist who pushed the boundaries of traditional art and helped pave the way for the art of the 20th century. His exploration of movement, form, and light continues to inspire artists and captivate audiences, ensuring his place as a master of modern art. He stands as a complex but undeniably crucial figure in the evolution of artistic expression, a testament to the power of observation, dedication, and unwavering artistic vision.