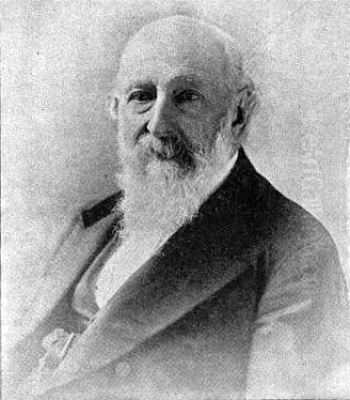

George Loring Brown (1814–1889) stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American landscape painting. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, he carved out a unique career path that saw him spend considerable time in Europe, particularly Italy, where he absorbed the traditions of European masters while developing his own distinct style. Renowned for his idealized and atmospheric landscapes, Brown earned the affectionate nickname "Claude" Brown due to his deep admiration for the seventeenth-century French master Claude Lorrain, whose compositional structures and handling of light profoundly influenced his work. His life and art represent a fascinating bridge between American artistic sensibilities and European academic traditions.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Boston

George Loring Brown was born in Boston on February 2, 1814. From a young age, he harbored ambitions of becoming an artist. His initial training was not in painting but in the craft of wood engraving. He apprenticed under Alonzo Hartwell, a Boston wood engraver, learning the meticulous techniques of the trade. Some accounts also mention study with another engraver named Abel Brown. This early experience likely honed his skills in draftsmanship and composition.

During his youth, Brown also worked as an illustrator, notably creating images for children's books. This practical application of his artistic skills provided him with income and further experience. Interestingly, his talents were not confined to the visual arts. Brown was involved with the Forrest Dramatic Club in Boston, where he reportedly displayed considerable theatrical flair and energy, suggesting a multifaceted creative personality even in his formative years.

His determination to pursue painting as his primary vocation remained strong. A pivotal moment occurred when one of his early paintings attracted the attention of a Boston collector. The sale of this work provided Brown with the necessary funds to embark on his first journey to Europe in 1832, seeking the advanced artistic training unavailable to him in America at the time.

First European Sojourn and Parisian Training

Arriving in Europe in 1832, the young Brown made his way to Paris, then a major center of the art world. There, he sought formal instruction and enrolled in the studio of Eugène Isabey. Isabey was a prominent French painter known for his romantic seascapes and historical scenes, and importantly, he had also been an instructor to the esteemed American painter Washington Allston. Studying with Isabey for a period, reportedly around four years, exposed Brown to contemporary French Romanticism and academic techniques.

However, the most profound influence Brown encountered during this period was the work of the Old Masters, particularly Claude Lorrain. Brown spent countless hours studying and copying Claude's idealized landscapes in the Louvre. He was captivated by Claude's harmonious compositions, his masterful depiction of atmospheric perspective, and his signature use of warm, golden light to evoke poetic moods. Brown's emulation of Claude became so pronounced that it earned him the lasting nickname "Claude" Brown among his peers and patrons.

This period was crucial for shaping Brown's artistic vision. He absorbed the principles of classical landscape painting, learning how to construct idealized scenes that balanced natural observation with artistic convention. His time in Paris laid the foundation for the style that would characterize much of his career.

Return to Boston and Local Recognition

After his initial period of study in Europe, Brown returned to Boston. He brought back with him enhanced skills and a deeper understanding of European art. During this time, he benefited from the encouragement of Washington Allston, the leading figure in Boston's art scene and a connection from Brown's studies with Isabey. Allston's support would have been significant for a young artist seeking to establish himself.

Brown became an active participant in the local art community. He frequently exhibited his works at the Boston Athenæum, one of the primary venues for artists in the city at that time. These exhibitions helped to build his reputation and connect him with potential patrons. His European training and the Claudian influence evident in his work likely distinguished him from many of his local contemporaries. This interim period in Boston solidified his standing before he embarked on his longer and more definitive stay abroad.

The Italian Years: A Landscape Painter Abroad

Around 1839 or 1840, George Loring Brown returned to Europe, this time setting his sights on Italy. This marked the beginning of an extended expatriate period that would last for nearly two decades, until 1859. Italy, with its rich artistic heritage, stunning natural beauty, and historical associations, held immense appeal for landscape painters of the era. Brown established himself primarily in Florence and Rome, centers frequented by international artists and tourists.

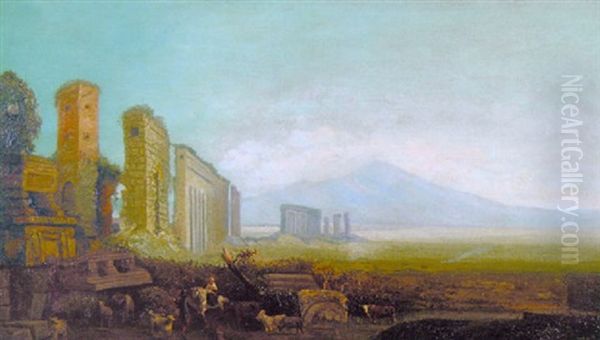

During these years, Brown supported himself largely by painting and selling Italian landscapes to the steady stream of affluent American and European travelers undertaking the Grand Tour. His works captured the iconic scenery of Italy – the Bay of Naples bathed in sunlight or moonlight, the romantic ruins of the Roman Campagna, picturesque views of Venice, and the sun-drenched hills of Tuscany. He became particularly known for these evocative Italian scenes.

His paintings from this period, such as the Moonlight View of Venice (1846), commissioned by Geo Tiffany of Baltimore and exhibited in New York, exemplify his focus. These works were praised for their precise brushwork, careful attention to detail, and, crucially, their delicate rendering of atmosphere and light, often imbued with a romantic sensibility. Living and working in Italy allowed Brown to immerse himself fully in the landscapes that inspired him and Claude Lorrain before him.

Artistic Style: The Influence of Claude and Italian Light

George Loring Brown's artistic style is most readily characterized by its debt to Claude Lorrain, filtered through a nineteenth-century American sensibility. He adopted Claude's compositional formulas, often featuring framing elements like trees or architecture, a receding series of planes leading the eye into the distance, and a focus on luminous skies and water. His landscapes are typically idealized rather than strictly topographical, aiming for beauty, harmony, and a sense of the picturesque or sublime.

His technique involved careful drawing and precise brushwork, building up forms with clarity. He paid close attention to the effects of light and atmosphere, often favoring the warm glow of sunrise or sunset, or the dramatic contrasts of moonlight, to create specific moods. This Claudian approach emphasized tranquility and a timeless quality in nature. His palette often featured the golden and rosy tones associated with his French predecessor.

Later in his career, particularly after his return from his long Italian sojourn, Brown's work showed an awareness of contemporary trends. Some sources suggest he introduced techniques reminiscent of the Italian Macchiaioli painters, a group active during his time in Italy known for their use of small patches (macchie) of color to capture effects of light and shadow more directly, prefiguring Impressionism. While perhaps not a full convert, this suggests Brown's style evolved, incorporating a slightly looser handling and greater emphasis on capturing fleeting light effects alongside his foundational Claudian structure. His training under the Romantic painter Eugène Isabey also contributed a certain dramatic flair visible in some works.

Return to America and Later Works

In 1859, after nearly twenty years abroad, George Loring Brown returned to the United States. He settled primarily in South Malden, Massachusetts (now part of Melrose), near his native Boston. While he continued to paint Italian scenes based on his sketches and memories – subjects for which he remained popular – he also turned his attention increasingly to American landscapes.

He made several sketching trips to the White Mountains of New Hampshire during the 1860s and 1870s. This region was a major center for American landscape painters associated with the Hudson River School and the related White Mountain School. Brown brought his European-honed sensibilities to these rugged American scenes, creating panoramic and often dramatic depictions of locations like Mount Washington.

His American landscapes, while depicting different scenery, often retained the compositional structure and atmospheric concerns of his Italian works. He sought to elevate the American landscape by treating it with the same artistic dignity traditionally accorded to European scenes. His later career thus involved a synthesis of his international experience and his engagement with the landscapes of his homeland. He passed away in Malden on June 25, 1889.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several key paintings represent George Loring Brown's style and achievements throughout his career:

The Crown of New England (1861): This large panoramic painting depicts the Presidential Range of the White Mountains. It showcases Brown's ability to handle grand scale and complex topography while imbuing the scene with atmospheric light. Its significance was underscored when it was purchased by Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), during his visit to the United States in 1860-61, bringing Brown considerable prestige.

Bay of New York (dated variously as 1861 or 1869): Another major work acquired by the Prince of Wales during the same visit. This painting demonstrates Brown's application of his landscape techniques to a bustling American scene, likely combining topographical elements with his characteristic atmospheric effects. Its royal acquisition further cemented Brown's international reputation.

View of Vesuvius from the Sea by Moonlight (1867): Representative of his popular Italian themes, this work likely captures the dramatic silhouette of Mount Vesuvius near Naples under moonlight. Such scenes allowed Brown to explore contrasts of light and shadow and evoke a sense of romantic mystery, appealing strongly to contemporary tastes.

Moonlight View of Venice (1846): An earlier example of his Italian work, painted during his long stay abroad. Venetian scenes, with their interplay of water, architecture, and light, were a favorite subject. This painting, commissioned and exhibited, highlights his early success in capturing the unique atmosphere of Italian locations.

Castle of Avo (1844) and Last Ray of Sunlight in the Campagna (1861): These titles suggest typical Italian subjects – picturesque castles and the expansive Roman countryside, often depicted at evocative times of day like sunset. They reflect his sustained engagement with the Italian landscape throughout his career.

These works collectively illustrate Brown's mastery of the idealized landscape, his skill in rendering light and atmosphere, and his ability to adapt his style to both European and American subjects.

Contemporaries and Connections

George Loring Brown's long career intersected with many important figures in the transatlantic art world of the nineteenth century. His primary teachers were the wood engravers Alonzo Hartwell and Abel Brown in Boston, and the French Romantic painter Eugène Isabey in Paris. His artistic lodestar was undoubtedly the seventeenth-century master Claude Lorrain.

In America, he received crucial early encouragement from Washington Allston, the dean of Boston painters. Brown's time in the White Mountains placed him in the geographical milieu of numerous Hudson River School and White Mountain School artists, even if his style remained distinct. These included figures like Thomas Cole (whose work influenced many American landscapists), Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Sanford Robinson Gifford, John Frederick Kensett, and Worthington Whittredge.

Evidence, such as correspondence held in archives, indicates direct contact with fellow landscape painter Alfred Thompson Bricher (1837-1908), known for his luminous coastal scenes often associated with Luminism, a style related to the Hudson River School. While the provided source material mentions John Elmer Edward and Edward Leavitt in lists alongside Brown, further research confirms Edward Leavitt was primarily a publisher (co-founder of Leavitt & Trow), not an artist, and there is no readily available information establishing a significant artistic connection between Brown and John Elmer Edward. Brown's network was primarily rooted in his training, his influences, and the broader community of landscape painters active in New England and Italy during his lifetime.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

George Loring Brown enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime, both in the United States and Europe. His works were sought after by prominent collectors, including royalty, which significantly boosted his reputation. He exhibited widely at major American institutions such as the Boston Athenæum, the Boston Art Club, the Brooklyn Art Association, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Historically, Brown is regarded as one of the leading American landscape painters of the generation that matured in the mid-nineteenth century. His significance lies partly in his role as a conduit for European landscape traditions, particularly the Claudian ideal, into American art. While the Hudson River School painters were forging a distinctly American approach often focused on detailed naturalism and nationalistic pride, Brown maintained a more cosmopolitan, Eurocentric style characterized by idealization and romantic atmosphere.

His nickname, "Claude" Brown, while affectionate, sometimes led to criticism that his work was derivative. However, he adapted the Claudian model to his own purposes and eventually applied it to American scenery as well. His technical skill, particularly in rendering light and atmosphere, was widely acknowledged. He stands as an important representative of the idealized, romantic landscape tradition in American art, offering a counterpoint to the more nationalistic or naturalistic trends of his time. His long expatriate period also makes him a key figure in the history of American artists working abroad.

Conclusion

George Loring Brown carved a distinctive path through the nineteenth-century art world. An American artist deeply indebted to European traditions, particularly the idealized landscapes of Claude Lorrain, he spent much of his productive life capturing the romantic beauty of Italy. Yet, he also engaged with the landscapes of his native New England, bringing his refined technique and atmospheric sensibility to American shores. Known as "Claude" Brown, he achieved international recognition for his meticulously crafted and evocative scenes. His work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of the classical landscape tradition and represents an important chapter in the transatlantic artistic exchanges that shaped American art.