George Lambert stands as a significant figure in the annals of British art history, primarily recognized for his contributions to landscape painting during the first half of the eighteenth century. Born in Kent around 1700, though some sources cite 1710, and passing away in London in 1765, Lambert navigated the burgeoning London art world, leaving a distinct mark both as a painter of idealized landscapes and as a highly respected theatre scene painter. His work bridged the gap between the dominant influence of Continental masters and the emergence of a native British school of landscape art, earning him considerable acclaim during his lifetime.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Details surrounding George Lambert's earliest years and initial training remain somewhat sparse, a common occurrence for artists of this period before the establishment of formal academies and more rigorous record-keeping. It is known, however, that he received foundational instruction from Warner Hassells, an artist about whom less is documented. More significantly, Lambert studied under John Wootton, a prominent painter known for his sporting scenes, battle pieces, and increasingly, his landscape paintings, which often emulated the classical style popularised by European artists.

Wootton's influence is discernible in Lambert's early works. Wootton himself was adept at capturing the grandeur of the English countryside, often incorporating topographical accuracy with elements borrowed from the idealized compositions of artists like Gaspar Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Lambert absorbed these lessons, developing a proficiency in composing balanced and harmonious scenes. This apprenticeship provided him not only with technical skills but also with an understanding of the artistic tastes and patronage systems of the time, which heavily favoured classical and Italianate styles.

A Dual Career: Theatre and Easel

Lambert's professional life was characterized by a successful dual practice. He gained considerable renown as a principal scene painter at London's theatres, most notably Lincoln's Inn Fields and later the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, under the management of John Rich. Scene painting in the eighteenth century was a demanding and collaborative craft, requiring artists to produce large-scale, often ephemeral, works that created convincing illusions for the stage. Lambert excelled in this field, becoming one of the most sought-after scene painters of his generation.

His work for the theatre provided a steady income and kept him connected to a vibrant cultural milieu that included actors, writers, and fellow artists. This environment undoubtedly fostered collaboration and exchange of ideas. The skills required for scene painting – rapid execution, bold effects, and an understanding of perspective and light on a grand scale – likely informed his approach to easel painting, although the latter allowed for greater refinement and permanence.

While excelling in the theatre, Lambert concurrently developed his reputation as a landscape painter working on canvas. This aspect of his career is perhaps more enduring in terms of surviving works and historical significance. He moved away from the sporting subjects of his master, Wootton, to focus primarily on landscape compositions, often inspired by the classical tradition but increasingly incorporating views of the British countryside.

The Influence of the Masters and the English Landscape

The landscape painting tradition in Britain during the early eighteenth century was heavily dominated by foreign artists or British painters closely emulating Continental styles. The idealized, Arcadian landscapes of Claude Lorrain and the more structured, classical compositions of Gaspar Poussin (Nicolas Poussin's brother-in-law and follower) set the standard for high art in landscape. Additionally, the wilder, more dramatic scenes of Salvator Rosa offered an alternative, picturesque model.

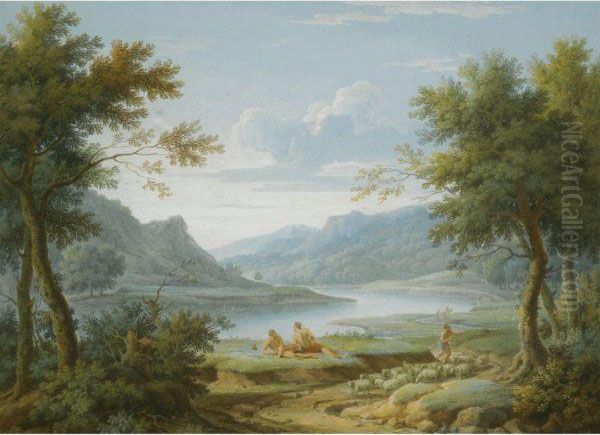

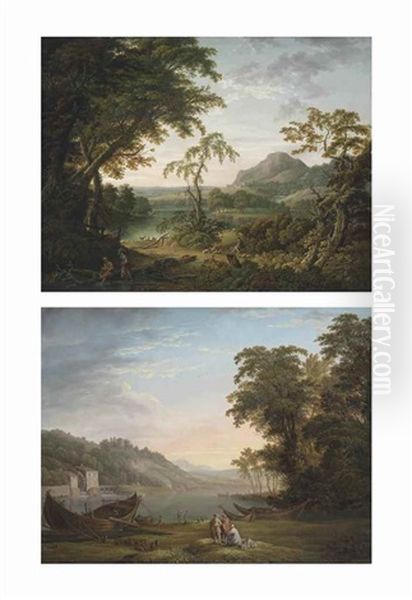

George Lambert skillfully navigated these influences. His landscapes often feature the hallmarks of the classical style: carefully balanced compositions, serene lighting, mythological or pastoral figures, and architectural elements like classical ruins or villas. These works catered to the prevailing aristocratic taste for art that evoked the grandeur of antiquity and the Italian Campagna. He became so adept in this manner that he earned the moniker "the English Poussin," signifying his mastery of the classical landscape idiom within a British context.

However, Lambert was not merely an imitator. He began to apply these compositional structures and stylistic conventions to depictions of actual English scenery. Works like A View of Box Hill, Surrey demonstrate this blend. While the composition might retain a classical balance, the subject is recognizably English. This move towards depicting native scenery, albeit often idealized, was a crucial step in the development of a distinctly British landscape tradition. He, along with contemporaries like Samuel Scott who focused on Thames views, helped elevate the status of local topography as a worthy subject for serious art.

Collaboration and Artistic Circles

The London art world of the mid-eighteenth century was a relatively small and interconnected community. Lambert was an active participant, known for his sociable nature. His collaboration with the celebrated painter and satirist William Hogarth is particularly noteworthy. Lambert painted the landscape backgrounds for Hogarth's large religious canvases, The Pool of Bethesda and The Good Samaritan, which were donated to St Bartholomew's Hospital in the late 1730s. This collaboration highlights Lambert's reputation as a specialist landscape painter whose skills were sought even by leading figure painters.

Lambert also collaborated with other artists, such as the engraver James Mason, who translated several of Lambert's landscape paintings into prints, thereby disseminating his compositions to a wider audience. It was also common practice for landscape painters of the era to have figures added to their canvases by specialist figure painters, although specific instances involving Lambert require careful documentation.

His social connections extended beyond direct artistic collaboration. In 1735, Lambert became a founding member of the Sublime Society of Beef Steaks, a convivial dining club that met weekly at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (where Lambert worked). The club's membership included prominent figures from the arts and theatre, such as Hogarth, the actor David Garrick, and the theatre manager John Rich. This association placed Lambert at the heart of London's cultural life.

Furthermore, Lambert was involved in early efforts by artists to organize and protect their professional interests. He associated with figures like George Vertue, the engraver and antiquary whose notebooks are a vital source for the period's art history, and William Hogarth in advocating for artists' rights. This milieu eventually led to Hogarth's successful campaign for the Engravers' Copyright Act of 1735.

The Foundling Hospital and the Society of Artists

George Lambert played a significant role in two key institutions that advanced the cause of British art before the founding of the Royal Academy. He was among the first artists to donate works to Captain Thomas Coram's Foundling Hospital. Established in the 1740s, the hospital became an unlikely but important public exhibition space after artists, encouraged by Hogarth, began decorating its Court Room with paintings. Lambert contributed several landscape roundels. These donations not only aided a charitable cause but also provided one of the few venues where contemporary British artists could display their work to the public, raising the profile of native talent.

Building on this spirit of collective action, Lambert was a key figure in the establishment of the Society of Artists of Great Britain. This group emerged from disagreements among artists exhibiting at the Foundling Hospital and aimed to create a more formal, independent body run by artists themselves. Lambert served as its first president in 1760 and again from 1761 until his death in 1765. The Society organised annual exhibitions, providing a crucial platform for artists like Thomas Gainsborough and the young Richard Wilson to showcase their work and fostering a sense of professional identity among British artists. Lambert's leadership position underscores his high standing among his peers.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

Lambert's style is characterized by its solid composition, often employing established formulas derived from Claude and Poussin, such as framing trees, receding planes, and a balance of light and shadow. His colour palette is typically restrained, favouring greens, browns, and blues, creating a harmonious, if sometimes conventional, effect. While influenced by the idealized tradition, his observation of nature is evident, particularly in the treatment of foliage and light effects in his English views.

Identifying his specific works can sometimes be challenging due to the collaborative nature of scene painting and potential confusion with contemporaries. However, several key easel paintings are attributed to him. Hilly Landscape with a Cornfield (c. 1733, Tate Britain) is an early example showing his assimilation of the classical style. Classical Landscape and A View of Box Hill, Surrey (both mentioned in source material, specific locations may vary) represent his engagement with both idealized Italianate scenes and specific English topography. His contributions to the Foundling Hospital and the backgrounds for Hogarth's paintings are also significant parts of his oeuvre.

Compared to the dramatic intensity of Salvator Rosa or the luminous poetry of Claude Lorrain, Lambert's work might appear more prosaic. Yet, its importance lies in its historical context. He provided a competent and respected British alternative to imported landscapes, adapting the esteemed classical style to native subjects and paving the way for the next generation. His paintings offered patrons sophisticated landscape art produced domestically.

Legacy and Influence

George Lambert died in 1765, reportedly on the same day the committee of the Society of Artists, of which he was president, passed a resolution to petition the King for the establishment of a Royal Academy. Although he did not live to see the Royal Academy founded in 1768, his efforts with the Society of Artists were instrumental in creating the conditions for its emergence.

His primary legacy lies in his role as a foundational figure in the British school of landscape painting. While Richard Wilson is often more emphatically called the "father of British landscape painting" for his more profound synthesis of Italian classicism and Welsh scenery, Lambert was a crucial precursor. He helped establish landscape as a respectable genre for British artists and patrons at a time when portraiture and historical painting held higher status. He demonstrated that British artists could competently engage with the prestigious classical landscape tradition.

His influence can be seen less in direct stylistic imitation by later major figures and more in his contribution to the professionalization of artists and the popularization of landscape subjects, including British views. He helped create the institutional structures (like the Society of Artists) and the market conditions that allowed landscape painters like Gainsborough (in his landscape mode), Wilson, and later John Constable and J.M.W. Turner to flourish.

Though many of his large-scale theatre scenes are lost due to their ephemeral nature, his surviving easel paintings, his documented collaborations with artists like Hogarth, and his leadership role in the Society of Artists secure his place as a pivotal figure in the development of British art during the eighteenth century. He stands alongside contemporaries like Jonathan Richardson, Francis Hayman, Samuel Scott, and Canaletto (during his London period) as part of the generation that laid the groundwork for the flourishing of British art in the later Georgian era. George Lambert's career exemplifies the transition occurring in British art, moving towards greater self-confidence and the establishment of its own distinct traditions.