Thomas Jones (1742–1803) stands as a significant, if for a long time overlooked, figure in the history of British art, particularly celebrated for his innovative approach to landscape painting. A Welshman by birth, his work, especially his oil sketches produced in Italy, displays a remarkable modernity and directness of observation that was ahead of its time. While he was a pupil of the great Richard Wilson, Jones forged his own path, creating images that resonate with a freshness and intimacy that continue to captivate audiences today. His career bridges the classical landscape tradition and the burgeoning Romantic sensibility, making him a fascinating artist whose contributions are now increasingly recognized.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in Trefonnen in Radnorshire, Wales, Thomas Jones hailed from a family of minor gentry. His early education was geared towards a career in the church, and he attended Jesus College, Oxford, from 1759. However, his true passion lay in art. After leaving Oxford without a degree, he moved to London in 1761 and began his artistic training. Initially, he studied under the drawing master William Shipley, whose school was a notable institution for aspiring artists.

The most formative period of his early training, however, commenced in 1763 when he became a pupil of the pre-eminent Welsh landscape painter Richard Wilson. Wilson, often dubbed "the father of British landscape painting," had himself spent considerable time in Italy and brought a classical, Arcadian sensibility to his depictions of both British and Italian scenery. Under Wilson's tutelage, Jones absorbed the principles of classical landscape composition, the handling of light, and the rich, tonal qualities that characterized his master's work. Jones's early paintings clearly reflect Wilson's influence, often depicting idealized Welsh landscapes imbued with a serene, classical air. He also began exhibiting, showing his works at the Society of Artists, of which he became a fellow in 1771 and later a director.

The Italian Sojourn: A Period of Profound Innovation

Like many artists of his generation, Thomas Jones embarked on the Grand Tour, a journey to Italy considered essential for artistic and cultural education. He set off in 1776, a pivotal moment in his career. His travels took him through France to Rome, where he initially based himself. Rome, with its ancient ruins and vibrant artistic community, provided ample inspiration. He associated with other British artists in the city, such as Jacob More, a Scottish landscape painter, the sculptor Thomas Banks, and the watercolourist John Robert Cozens, whose atmospheric Italian views were highly influential.

However, it was his time in Naples, where he resided from 1780 to 1783, that proved to be the most artistically revolutionary period for Jones. In Naples and its environs, he produced a remarkable series of small-scale oil sketches on paper. These works were not intended for public exhibition but were personal studies, executed directly from nature, or en plein air. This practice, while not entirely new, was pursued by Jones with an unprecedented directness and an eye for the unconventional. He befriended the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri, known as Don Titta, who was also interested in precise topographical views.

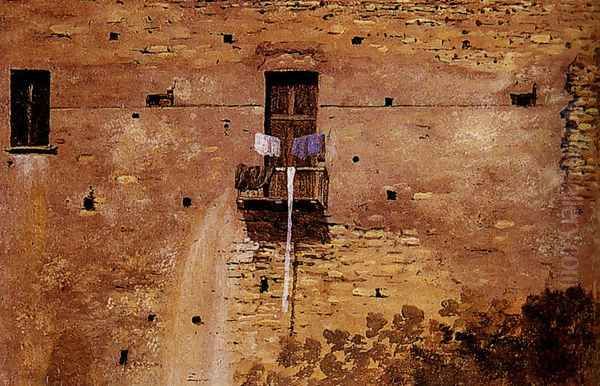

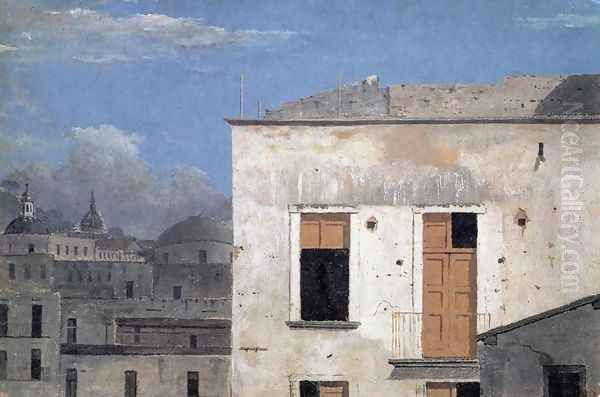

These Neapolitan sketches are characterized by their informality, their bold, often geometric compositions, and their keen observation of light and everyday reality. Instead of grand, idealized vistas, Jones often focused on seemingly mundane subjects: the weathered walls of buildings, rooftops cluttered with laundry, or glimpses of the Bay of Naples framed by urban structures. Works like "A Wall in Naples" (1782) and "Buildings in Naples" (often referred to as "Rooftops, Naples," 1782) are prime examples. "A Wall in Naples" is strikingly abstract for its time, a study of texture, light, and form on a sun-drenched wall, with minimal anecdotal detail. These sketches possess an immediacy and an almost photographic quality that prefigure later developments in landscape painting by artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and the Barbizon School.

Artistic Style: Observation, Light, and Composition

Thomas Jones's artistic style evolved throughout his career, but his most distinctive contributions lie in his innovative approach to landscape. While his earlier, larger exhibition pieces adhered more closely to the classical landscape tradition inherited from Richard Wilson, often featuring mythological or historical figures in carefully constructed settings, his Italian oil sketches reveal a different sensibility.

The hallmark of these sketches is their directness of observation. Jones painted what he saw, without idealization or overt narrative. This commitment to capturing the visual truth of a scene, however humble, was radical for its time. He had an exceptional ability to render the effects of Mediterranean light, capturing the strong contrasts of sun and shadow, the clarity of the atmosphere, and the subtle variations in colour. His palette in these sketches is often bright and luminous, applied with a fluid, confident touch.

Compositionally, Jones often chose unconventional viewpoints. He might look down onto a jumble of rooftops, focus on a fragment of a building, or frame a distant view with close-up architectural elements. This resulted in compositions that were often strikingly geometric and modern in feel. There's a sense of cropping and an interest in abstract pattern that seems to anticipate later artistic movements. Even in his more formal works, such as "The Bard" (1774), inspired by Thomas Gray's poem, which depicts a dramatic Welsh landscape with the lone figure of the bard, there is a powerful sense of place and atmosphere that transcends mere topographical accuracy, hinting at the emerging Romantic spirit. This work can be seen in dialogue with the dramatic landscapes of contemporaries like Philip James de Loutherbourg or Joseph Wright of Derby, though Jones's approach often retained a more personal, less theatrical quality.

Key Representative Works

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Thomas Jones's artistic achievement and innovation.

"A Wall in Naples" (1782, National Gallery, London) is perhaps his most famous and revolutionary work. This small oil sketch on paper depicts a section of a sunlit wall, with a window and washing hanging out to dry. Its power lies in its simplicity and its focus on the play of light, texture, and abstract form. It is a testament to Jones's ability to find beauty and artistic interest in the most unassuming subjects, a quality that makes it feel remarkably modern.

"Buildings in Naples" (or "Rooftops, Naples," 1782, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) is another iconic oil sketch. Looking down from a high vantage point, Jones captures a dense cluster of Neapolitan rooftops, with glimpses of daily life. The composition is a complex interplay of geometric shapes and varied textures, bathed in the clear Italian light. It demonstrates his skill in organizing a seemingly chaotic scene into a coherent and visually engaging image.

"The Bard" (1774, National Museum Wales, Cardiff) represents his earlier, more formal style, heavily influenced by Richard Wilson and the sublime aesthetics of the period. Based on Thomas Gray's poem of the same name, it depicts the last Welsh bard cursing the invading English army of King Edward I. The landscape is wild and dramatic, reflecting the passionate intensity of the subject. While different in style from his Neapolitan sketches, it showcases his ability to create powerful, evocative landscapes within a more traditional framework.

Other notable works include various views around Lake Albano and Lake Nemi near Rome, which, while sometimes more conventional, still display his sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His watercolour studies, though less groundbreaking than his oils on paper, also demonstrate his skill as a draughtsman and his keen observational abilities, aligning him with other watercolourists of the period like William Pars and Francis Towne, with whom he sometimes travelled or associated.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Thomas Jones's artistic development was shaped by his interactions with several contemporary artists. His primary mentor, Richard Wilson, provided the foundational training in classical landscape. While Jones eventually moved beyond Wilson's more idealized style, the lessons learned in terms of composition, light, and tonal harmony remained influential.

During his time in Italy, Jones was part of a vibrant community of British artists. He knew Jacob More, a Scottish painter who also specialized in classical landscapes and was highly successful in Rome. He was acquainted with John Robert Cozens, whose evocative watercolour landscapes of Italy, with their subtle gradations of tone and melancholic beauty, were highly esteemed. Jones also encountered the sculptor Thomas Banks, a leading figure of British Neoclassicism.

His friendship with the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri (Don Titta) in Naples was significant. Lusieri was known for his meticulously detailed topographical watercolours, and their shared interest in accurate depiction may have been mutually reinforcing, even if Jones's oil sketches were more painterly and immediate.

Jones also travelled with or encountered fellow artists like William Pars, an accomplished watercolourist known for his precise renderings of classical antiquities and landscapes, and Francis Towne, whose distinctive watercolour style, characterized by strong outlines and flat washes of colour, was also highly individual. The painter John Hamilton Mortimer, known for his romantic and often dramatic figure subjects, including banditti scenes popular at the time, was another contemporary whose work Jones would have known, and they even collaborated on occasion before Jones left for Italy.

While not a direct associate in the same way, Jones's work can be seen in the broader context of other landscape painters of the era, such as Thomas Gainsborough, whose landscapes, though often secondary to his portraiture, showed a more naturalistic and less idealized approach than Wilson's. The topographical tradition, exemplified by artists like Paul Sandby, also formed part of the artistic landscape against which Jones's innovations can be measured. Even the more experimental approaches to landscape composition, such as those explored by Alexander Cozens with his "blot" technique, indicate a period of exploration and change in British landscape art.

Later Life, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

In 1783, Thomas Jones left Italy and returned to Britain. His return was partly prompted by news of his father's death and the need to manage family affairs. He continued to paint, producing larger exhibition pieces based on his Italian studies, but these often lacked the spontaneity and freshness of his on-the-spot sketches. He exhibited at the Royal Academy, but his work did not achieve widespread acclaim during this later period.

A significant change in his life occurred in 1787 when he inherited the family estate of Pencerrig in Radnorshire upon the death of his elder brother. He largely abandoned professional painting around 1789, settling into the life of a country squire. He married Maria Moncke, with whom he had been living in Naples and had two daughters. Though he continued to sketch for his own pleasure, his public artistic career effectively ended.

For many years after his death in 1803, Thomas Jones remained a relatively obscure figure, overshadowed by his master Richard Wilson and other more prominent landscape painters of the 18th century. His true significance, particularly the innovative nature of his Italian oil sketches, was not widely recognized until the 20th century. A crucial moment in his posthumous rediscovery was the publication of his "Memoirs" in 1951 by the Walpole Society. These candid and engaging memoirs provided valuable insights into his life, his travels, and the art world of his time.

The subsequent exhibition and scholarly attention given to his oil sketches, particularly from the 1950s onwards, led to a re-evaluation of his place in art history. Critics and art historians began to appreciate the remarkable modernity of these works, their directness of vision, and their anticipation of later plein-air painting. Artists like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who revolutionized British landscape painting in the early 19th century, would have found a kindred spirit in Jones's approach to capturing the fleeting effects of nature, had his sketches been widely known. His influence is more clearly seen as a precursor to the naturalism of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and the painters of the Barbizon School in France, who also championed direct observation from nature.

Legacy and Conclusion

Thomas Jones's legacy is primarily defined by his extraordinary Italian oil sketches. These small, intimate works, created for his own study and pleasure, reveal an artist of remarkable originality and foresight. His ability to find profound beauty in the everyday, his unconventional compositions, and his sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere mark him as a pioneer. He demonstrated that landscape painting could be more than just the depiction of grand scenery or classical idylls; it could also be a personal and immediate response to the visual world.

While his more formal exhibition pieces connect him to the established traditions of his time, it is in the freedom of his sketches that his true genius lies. They offer a glimpse into a more private, experimental side of 18th-century art practice and highlight the importance of direct engagement with nature. Today, Thomas Jones is recognized as a key figure in the development of European landscape painting, an artist whose quiet innovations had a resonance far beyond his own lifetime. His work continues to inspire with its honesty, its freshness, and its timeless appeal, securing his position as a significant Welsh contributor to the broader narrative of British and European art.