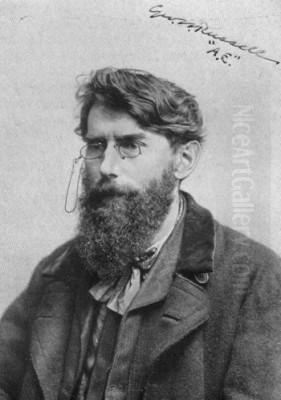

George William Russell, more famously known by his pseudonym "AE" (sometimes written as A.E.), stands as one of the most versatile and influential figures of the Irish Renaissance. Born on April 10, 1867, in Lurgan, County Armagh, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), and passing away on July 17, 1935, in Bournemouth, England, Russell's life was a tapestry woven with threads of poetry, painting, mysticism, journalism, and fervent Irish nationalism. He was not merely a participant but a pivotal force in the cultural and political reawakening of Ireland at the turn of the 20th century, leaving an indelible mark on its artistic and intellectual landscape.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Russell's origins were modest. He was born into a family of limited means; his father, Thomas Russell, was an accountant, and his mother, Mary Anne Armstrong Russell, a homemaker. The economic struggles of his early years in Lurgan perhaps sowed the seeds of his later commitment to social reform and cooperative movements. When Russell was eleven, his family relocated to Dublin, a move that would prove crucial for his development. The city, then a burgeoning hub of intellectual and artistic ferment, provided the backdrop for his burgeoning talents.

In Dublin, Russell's artistic inclinations led him to the Metropolitan School of Art. It was here, and later at the Royal Hibernian Academy schools, that he began to formally hone his skills as a painter. More significantly, it was during this period, around 1884, that he met William Butler Yeats. This encounter blossomed into a lifelong friendship and a profoundly significant intellectual partnership. Together, they would become central figures in the Irish Literary Revival, a movement dedicated to fostering a distinctly Irish literature and art, drawing inspiration from Gaelic mythology, folklore, and the Irish landscape.

The Emergence of "AE": A Mystical Moniker

The adoption of the pseudonym "AE" is a story steeped in Russell's characteristic mysticism. It is said to have originated from a visionary experience. One version recounts that while working as a clerk, he had a vision of the word "Æon" on a packing case, which he initially used. Another, perhaps more cited, version suggests that while proofreading an article, a printer queried a misspelling of "aeon." Russell, liking the brevity and esoteric resonance of the first two letters, adopted "AE." He himself explained that "AE" was derived from "Æon," a Gnostic term signifying the first created being or a divine emanation. This choice of name was deeply reflective of his lifelong preoccupation with the spiritual, the esoteric, and the ancient wisdom traditions.

Russell's mystical inclinations were not a late development. From a young age, he reported experiencing visions and moments of profound spiritual insight. He claimed to have clairvoyant abilities, seeing pre-cognitive visions and nature spirits. These experiences, which began around 1883 and continued throughout his adult life, profoundly shaped his worldview and became a central wellspring for both his literary and artistic creations. He was deeply drawn to Theosophy, a spiritual movement founded by Helena Blavatsky, which sought to explore universal truths underlying all religions and philosophies.

AE the Writer: Poet, Essayist, and Editor

AE's literary output was prolific and diverse, encompassing poetry, essays, plays, and art criticism. He began publishing in the 1880s, and his work quickly gained recognition for its lyrical beauty and profound spiritual depth. His first collection of poems, Homeward: Songs by the Way (1894), established his reputation as a significant new voice in Irish literature. This was followed by other notable collections such as The Earth Breath and Other Poems (1897) and The Divine Vision and Other Poems (1904).

His poetry is characterized by its mystical themes, its celebration of nature as a conduit to the divine, and its exploration of Celtic mythology. Works like The Candle of Vision (1918), a prose work detailing his mystical experiences and philosophy, and Song and Its Fountains (1932), which explored the sources of poetic inspiration, further illuminate his spiritual journey. Imaginations and Reveries (1915), a collection of essays and stories spanning twenty-five years, showcased his nationalist sentiments and his deep spiritual concerns. His novel The Avatars: A Futurist Fantasy (1933) continued his exploration of spiritual themes within a fictional narrative.

Beyond his creative writing, AE was an influential editor. He helmed The Irish Homestead (1905–1923), the journal of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS), and later The Irish Statesman (1923–1930). Through these publications, he championed the cause of agricultural cooperation, economic self-sufficiency for Ireland, and the broader cultural revival. His editorials were widely read and respected, offering insightful commentary on a range of social, political, and cultural issues. He provided a platform for many emerging Irish writers, including Patrick Kavanagh, who later acknowledged AE's early encouragement.

AE the Artist: Visionary Painter

Parallel to his literary endeavors, AE cultivated a significant career as a painter. His artistic training at the Metropolitan School of Art and the Royal Hibernian Academy provided him with a solid technical foundation, but his vision was uniquely his own, deeply infused with his mystical perceptions. He is considered one of Ireland's most distinguished Symbolist painters.

His paintings often depict ethereal figures—fairies, spirits, and divine beings—set against the backdrop of the Irish landscape, particularly the rugged beauty of Donegal and the West of Ireland. He saw these landscapes not merely as picturesque scenes but as places imbued with "psychic energy" and spiritual significance. His canvases are characterized by their soft, luminous light, often employing a palette of warm, earthy tones or twilight hues that evoke a dreamlike, otherworldly atmosphere. Children also feature prominently in his work, often portrayed with an innocence that connects them to the spiritual realm.

Among his representative paintings, Three Girls Playing in the Sand Dunes, Donegal captures his gentle observation of youth in a natural, almost mystical setting. Apparel'd in Celestial Light is another key work, its title and imagery directly reflecting his preoccupation with the divine and the transcendent. Other works, such as The Winged Horse or paintings depicting figures from Celtic mythology, further underscore his visionary style.

AE's artistic style shows the influence of several artists, though he forged a path distinctly his own. He admired the work of the French Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet for their sensitive portrayal of nature and rural life. The rich, impasto surfaces and dreamlike qualities found in the work of Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli also resonated with him. Perhaps most significantly, the visionary art of William Blake, with its fusion of poetry, mysticism, and visual expression, provided a powerful precedent for AE's own artistic aims. He also expressed admiration for the Symbolist Gustave Moreau.

He was not an isolated figure in the Dublin art scene. He was a contemporary of artists like Sarah Purser, a leading portraitist and stained-glass artist who was instrumental in establishing An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass), a cooperative for stained-glass artists. Other notable Irish painters of his era included Nathaniel Hone the Younger, known for his atmospheric landscapes, and Walter Osborne, whose work captured scenes of Irish life with an Impressionistic sensibility. John Butler Yeats, the father of W.B. and Jack B. Yeats, was also a prominent portrait painter during this period.

AE's connection with W.B. Yeats extended into the art world. In 1902, the influential Irish-American lawyer and art collector John Quinn commissioned AE to paint a portrait of W.B. Yeats, a testament to their close bond and AE's recognized skill as a painter. AE's own visionary landscapes are also thought to have inspired the younger Jack B. Yeats, W.B.'s brother, particularly in his depictions of rural Irish life and folklore, though Jack developed a much more expressionistic style. AE also collaborated on painting excursions, for instance, with the artist Letitia Hamilton, with whom he visited Garinish Island and painted landscapes. Hamilton's work, like Hungry Hill, often captured the Irish scenery with a vibrant, post-impressionistic touch.

The broader European Symbolist movement, with artists like Odilon Redon in France, known for his dreamlike and often melancholic imagery, or Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, celebrated for his serene and allegorical murals, shared thematic concerns with AE, even if direct influence is harder to trace. The Pre-Raphaelites, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, with their emphasis on literary themes, medievalism, and spiritual intensity, also formed part of the artistic currents that fed into the Celtic Revival and, by extension, the milieu in which AE worked.

AE and the Irish Literary Revival

AE was a cornerstone of the Irish Literary Revival, a movement that sought to create a modern Irish literature in English that was nevertheless rooted in Irish identity, mythology, and language. His friendship and collaboration with W.B. Yeats were central to this endeavor. They shared a deep interest in Irish folklore, mysticism, and the creation of a national theatre. While Yeats was more focused on crafting a high literary art, AE's vision was perhaps more encompassing, seeking a spiritual regeneration for the entire nation.

He was a familiar figure in the literary circles of Dublin, which included luminaries such as Lady Augusta Gregory, a playwright, folklorist, and co-founder of the Abbey Theatre, and J.M. Synge, whose plays controversially but powerfully depicted Irish rural life. AE's home became a salon for writers, artists, and thinkers, a place where ideas were exchanged and new talents nurtured. He was known for his generosity in supporting younger writers, offering them advice, encouragement, and publication opportunities in the journals he edited. James Joyce, another towering figure of Irish modernism, knew AE, and AE even makes a fleeting appearance in Ulysses.

His contribution to the Revival was multifaceted: as a poet whose work embodied its ideals, as an editor who provided a platform for its voices, and as a thinker whose mystical nationalism gave it a unique spiritual dimension. He believed that Ireland's cultural rebirth was intrinsically linked to a spiritual awakening, a rediscovery of its ancient soul.

AE the Theosophist and Mystic

AE's mysticism was not a mere artistic affectation; it was the bedrock of his being. He was deeply involved in the Theosophical Society, joining its Dublin Lodge, which he helped establish with W.B. Yeats and Charles Johnston. Theosophy, with its eclectic blend of Eastern religions, Western esoteric traditions, and Gnosticism, provided a framework for his spiritual explorations. He was particularly drawn to the teachings of Madame Blavatsky and later Annie Besant.

He also participated in the Hermetic Society, another group dedicated to esoteric studies. His writings, both prose and poetry, are replete with Theosophical concepts: the idea of a universal divine consciousness, reincarnation, karma, and the interconnectedness of all life. The Candle of Vision is perhaps his most explicit exposition of his mystical philosophy, detailing his methods for attaining visionary states and his understanding of the spiritual realms. He believed in the existence of a "Great Breath" or Anima Mundi, a world soul that animated all of creation, and sought to attune himself to its rhythms through meditation and contemplation of nature.

His mystical beliefs were not separate from his Irish nationalism. He envisioned a future Ireland that would be a spiritual beacon for the world, a "communion of saints and heroes," drawing on its ancient Celtic heritage of spiritual wisdom. This fusion of mysticism and nationalism distinguished him even within the diverse landscape of the Irish Revival.

AE the Social Reformer and Nationalist

Beyond his artistic and spiritual pursuits, AE was a practical idealist, deeply committed to improving the material conditions of the Irish people. His most significant contribution in this sphere was his work with the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS), founded by Sir Horace Plunkett. From 1897, AE worked as an organizer for the IAOS, traveling extensively throughout rural Ireland, helping to establish cooperative banks and creameries.

He believed that economic cooperation was essential for the empowerment of Irish farmers and the overall prosperity of the nation. His experiences in rural Ireland provided him with a firsthand understanding of the challenges facing the country and informed his writings in The Irish Homestead. He advocated for a holistic vision of national development, one that integrated economic self-reliance, cultural revival, and spiritual growth.

His nationalism was passionate but also inclusive and pacifist. While he supported Irish independence, he was wary of narrow, chauvinistic forms of nationalism. He envisioned an Ireland that was culturally distinct and politically sovereign but also open to the world and committed to universal human values. His pacifism became particularly evident during the turbulent years of the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

Several anecdotes offer glimpses into AE's personality. His pen name itself, and the stories surrounding its origin, highlight his mystical leanings. His lifelong friendship with W.B. Yeats, though occasionally strained by their differing temperaments and approaches, remained a constant in both their lives.

One amusing story recounts how D.P. Moran, the sharp-tongued editor of The Leader, a nationalist newspaper often critical of the literary revivalists, nicknamed AE "the hairy fairy" due to his long beard and otherworldly preoccupations. While perhaps intended derisively, the moniker captured something of AE's unique persona.

His spiritual journey also involved a departure from conventional religion. In his youth, AE lost his Christian faith, finding certain tenets of orthodox Christianity to be unreasonable. This intellectual honesty and willingness to question established doctrines were characteristic of his independent spirit. His search for spiritual truth led him instead to Theosophy and other esoteric traditions.

Later Life, Legacy, and International Recognition

AE continued to write, paint, and lecture into his later years. He undertook several lecture tours in the United States, where his ideas on mysticism, art, and Irish culture were well received. His international reputation was also bolstered by his inclusion in significant art exhibitions. Notably, he was one of the few Irish artists whose work was featured in the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show in New York (though the initial prompt referred to an "American art" exhibition, the Armory Show was the key event that introduced European modernism to America and included some American and Irish artists). This exposure helped to bring his art to a wider international audience.

After the death of his wife, Violet Russell (née North), in 1932, and with the demise of The Irish Statesman due to financial difficulties, AE felt increasingly isolated in Ireland. He moved to England in 1933 and died in Bournemouth two years later, in 1935, from cancer. He was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin, a final return to the city that had been the heart of his life's work.

George William Russell's legacy is immense and multifaceted. As a poet, he contributed a unique mystical voice to Irish literature. As a painter, he created a body of visionary work that captured the spiritual essence of the Irish landscape. As an editor and essayist, he was a thoughtful commentator on the issues of his day and a mentor to a generation of writers. As a mystic and Theosophist, he explored the depths of spiritual experience. And as a social reformer and nationalist, he worked tirelessly for the betterment of Ireland. He remains a vital figure for understanding the cultural, spiritual, and political currents that shaped modern Ireland.

Exhibitions and Archival Presence

AE's work and life continue to be subjects of interest and study, preserved through exhibitions and archival collections.

Exhibitions such as The AE Russell Story at the Aonach Mhacha Centre in Armagh have showcased his life, paintings, and poetry, offering contemporary audiences a comprehensive view of his contributions. Another exhibition, titled AE: An Irish Renaissance Man, drew from museum collections to display works reflecting his deep engagement with Irish mythology and the spiritual world.

His literary and personal papers are held in several important archives. The National Library of Ireland holds a significant collection of his letters and memorabilia (MS Coll 00062), including documents related to his American lecture tours in the late 1920s. The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin also houses a substantial collection of AE's materials, including poetry drafts, correspondence, and articles.

Scholarly works and bibliographies further document his output. Printed Writings by George W. RUSSELL: A Bibliography, compiled by Alan Denson, provides a detailed record of his published works, including information on his paintings and portraits. Biographies such as Henry Summerfield's That Myriad-minded Man: A Biography of George William Russell "AE" offer comprehensive accounts of his life and multifaceted career. His own collection, Imaginations and Reveries (1916), remains a key source for understanding his thought, gathering articles and stories that articulate his nationalist ideals and spiritual preoccupations.

Conclusion: An Enduring Visionary

George William Russell, "AE," was more than just a poet or a painter; he was a visionary in the truest sense of the word. He saw beyond the surface of things, perceiving a world imbued with spiritual significance, and dedicated his life to expressing this vision through a remarkable array of talents. His deep love for Ireland, his commitment to its cultural and economic flourishing, and his profound spiritual insights combined to make him a unique and enduring figure. In the pantheon of Irish cultural heroes, AE stands tall as a "myriad-minded man" whose work continues to inspire and resonate, a testament to a life lived in passionate pursuit of beauty, truth, and the spiritual regeneration of his homeland. His influence on contemporaries like W.B. Yeats and younger generations of artists and writers, coupled with his direct contributions to social and economic reform, cement his place as a pivotal architect of modern Irish identity.