Introduction: A Multifaceted Symbolist

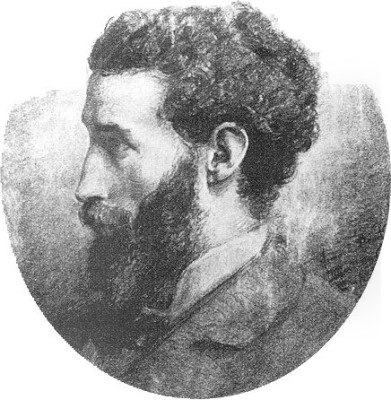

Armand Point (1861-1932) stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure within the rich tapestry of French Symbolism. Born in the vibrant atmosphere of Algiers and concluding his life's journey in Naples, Point was a versatile artist – a painter, an engraver, and a designer – whose career navigated the currents of late 19th and early 20th-century art. He moved from the sun-drenched realism of Orientalist scenes to the ethereal, mystical realms of Symbolism, leaving behind a body of work characterized by its technical refinement, intellectual depth, and a unique synthesis of historical influences. His association with key Symbolist initiatives, particularly the Salon de la Rose + Croix, cemented his place within the movement's idealistic core.

Algerian Roots and Orientalist Beginnings

Armand Point entered the world in 1861 in Algiers, Algeria, then a French territory. Born to a French father and a Spanish mother, his early environment was steeped in the cultural crossroads of North Africa. This upbringing profoundly influenced the initial phase of his artistic output. Like many European artists of his time, Point was drawn to the perceived exoticism and picturesque qualities of the region. His early works predominantly featured Orientalist themes, capturing the bustling energy of Algerian street scenes, the vibrant chaos of local markets, and the evocative presence of musicians.

These initial paintings showcased a keen observational skill and a sensitivity to the effects of light and atmosphere, typical of the Orientalist genre popularized earlier by artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Point's depictions were not merely documentary; they often imbued the scenes with a romantic sensibility, focusing on the textures, colours, and human interactions that defined daily life in Algiers. This period laid the foundation for his technical proficiency, particularly in rendering detail and capturing mood, skills that would later be transformed in the service of different artistic ideals. Some accounts suggest he was orphaned at a young age, around nine, which may have precipitated his eventual move to mainland France to pursue formal artistic training.

Parisian Education and Evolving Influences

Seeking to further his artistic development, Point relocated to Paris, the undisputed centre of the European art world. He initially enrolled at the Rollin College, continuing to develop his craft. While specific mentors from this early Parisian period are not clearly documented, it was a time of absorption and refinement. His formal training intensified when he entered the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under the guidance of recognized academic painters Auguste Herst and Fernand Cormon. Cormon, known for his historical and prehistoric scenes, ran a popular atelier that attracted numerous students, including future luminaries like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh, although Point's path would diverge significantly from theirs.

During his time in Paris, Point's artistic horizons expanded beyond the academic and Orientalist traditions. He became increasingly receptive to new currents, particularly the influence emanating from Britain. The aesthetic theories of John Ruskin, with their emphasis on nature, craftsmanship, and moral beauty, resonated with him. Concurrently, he discovered the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly artists like Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Their idealized figures, meticulous detail, rich colours, and penchant for medieval and literary themes offered a compelling alternative to French Realism and Impressionism, steering Point towards a more poetic and idealistic form of expression.

The Italian Epiphany: Renaissance Revival

A pivotal moment in Armand Point's artistic evolution occurred in 1894. Accompanied by his wife, Hélène Linder, he embarked on a transformative journey to Italy. This trip was not merely a tour but a profound immersion in the art of the Italian Renaissance. Point was deeply moved by the masterpieces he encountered, particularly the works of the Florentine Quattrocento. The ethereal grace of Sandro Botticelli and the intellectual depth and technical mastery of Leonardo da Vinci left an indelible mark on his artistic consciousness.

This encounter with the Italian masters catalyzed a significant shift in his style and aspirations. Point became convinced that the path forward lay in looking back, in reviving the techniques and spirit of the 15th century. He began experimenting with older methods, including tempera painting, seeking to emulate the clarity, precision, and luminous quality he admired in the early Renaissance works. This wasn't simply stylistic imitation; it was a philosophical commitment to an ideal of beauty and craftsmanship that he felt had been lost in contemporary art. The Italian journey solidified his move away from observed reality towards a more stylized, symbolic, and historically informed aesthetic.

Embracing Symbolism: A Turn Inward

Following his experiences in Italy and his engagement with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, Point fully embraced the Symbolist movement. This represented a conscious rejection of the dominant trends of Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet, and Naturalism, as well as the Impressionists' focus on fleeting sensory perception. Symbolism offered Point a framework for exploring the inner world of dreams, ideas, myths, and emotions. It prioritized suggestion over description, the spiritual over the material, and the eternal over the ephemeral.

Point's Symbolist works delved into allegory, mythology, and legend, often featuring enigmatic figures in dreamlike settings. He sought to create images that resonated on a deeper, more intuitive level, using visual language to evoke moods and concepts that lay beyond the reach of straightforward representation. His commitment to Symbolism was not just aesthetic but also philosophical, aligning with the movement's often anti-modernist stance and its quest for a more profound, spiritually resonant art form in an age perceived as increasingly materialistic and superficial. He became a key proponent of this introspective and often mystical approach to art.

The Salon de la Rose + Croix: An Idealistic Bastion

Armand Point's dedication to Symbolist ideals found a powerful outlet through his involvement with the Salon de la Rose + Croix. He was a key figure in this venture, collaborating closely with its charismatic and eccentric founder, Joséphin Péladan. Péladan, a writer and occultist, established the Salons in 1892 as a showcase for art that adhered to specific mystical, religious, and idealistic principles. The Salons explicitly rejected realism, landscape, and scenes of modern life, favouring instead legend, myth, allegory, and dream.

Point was not just a participant but a central figure within this circle, exhibiting regularly and embodying the Salon's aesthetic and spiritual aspirations. The Rose + Croix Salons became important, if short-lived, platforms for international Symbolism, attracting artists who shared a similar inclination towards the esoteric and the idealized, such as the Belgian artists Fernand Khnopff and Jean Delville, the Swiss Carlos Schwabe, and others who sought an art form detached from mundane reality. Point's association with Péladan and the Salon firmly positioned him within the most overtly spiritual and anti-materialist wing of the Symbolist movement.

The Atelier Haute-Claire: Art and Craft United

Driven by his belief in the unity of the arts and inspired by the ideals of Ruskin and perhaps the English Arts and Crafts movement led by figures like William Morris, Point sought to extend his artistic vision beyond painting and engraving. Around 1896, he established a workshop community known as the Atelier Haute-Claire in Marlotte, a village near the Forest of Fontainebleau that had long attracted artists. This initiative aimed to revive traditional craftsmanship and integrate art into everyday life, countering the perceived soullessness of industrial production.

At Haute-Claire, Point and his collaborators produced a range of applied arts objects, including furniture, ceramics, enamels, embroidery, and jewellery. These pieces often displayed a distinct medieval or Renaissance revival style, characterized by intricate ornamentation, fine materials, and symbolic motifs. The workshop embodied Point's holistic vision of art, where the creation of beautiful, handcrafted objects was seen as a vital part of a meaningful artistic practice. It represented a practical application of his rejection of materialism and his desire to infuse the lived environment with aesthetic and spiritual value, echoing the broader Arts and Crafts philosophy of elevating craftsmanship to the level of fine art.

Artistic Style: Synthesis and Symbol

Armand Point's mature artistic style is a fascinating synthesis of his diverse influences, unified by a Symbolist sensibility. His work is characterized by a meticulous technique, often employing tempera or detailed oil painting methods reminiscent of the early Renaissance masters he admired, particularly Botticelli, whose influence is often noted in the linear grace of Point's figures and the treatment of hair and drapery. The precision learned during his early Orientalist phase was now applied to idealized forms and symbolic narratives.

His compositions frequently draw on mythological or allegorical themes, populated by elegant, often androgynous figures rendered with a smooth, polished finish. There is a strong emphasis on line and contour, combined with a carefully controlled palette that often favours rich, jewel-like colours or subtle, harmonious tones. Light is used symbolically rather than naturalistically, creating an atmosphere of mystery and otherworldliness. Elements borrowed from the Pre-Raphaelites, such as elaborate costumes, detailed settings, and a certain melancholic or contemplative mood, are seamlessly integrated. His work as an engraver and etcher, such as the illustrations for the Golden Legend, further demonstrates his mastery of line and intricate detail. Overall, his style projects an aura of timelessness, deliberately archaic yet distinctly personal, aiming for a beauty that transcends the everyday.

Representative Works: Visions in Paint and Print

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Armand Point's Symbolist vision. L'Éternelle Chimère (The Eternal Chimera), painted around 1895-96, is a quintessential example. It depicts a mythical creature, part woman, part beast, embodying unattainable ideals or perhaps dangerous illusions. The rendering is precise, the atmosphere dreamlike, showcasing his blend of Renaissance technique and Symbolist content.

La Sirène (The Siren), created in 1897, explores another classic Symbolist trope – the femme fatale, alluring and perilous. The siren figure, rendered with Point's characteristic elegance and linearity, emerges from a stylized sea, embodying themes of temptation, mystery, and the dangerous beauty of nature and the subconscious.

Saint George Terrassant le Dragon (Saint George Slaying the Dragon), also from 1897, tackles a traditional subject imbued with Symbolist meaning. It likely represents the triumph of spirit over matter, or good over evil, presented with a decorative, almost heraldic quality that reflects his interest in medieval aesthetics and the applied arts.

His work L'Annonciation (The Annunciation), if correctly identified (as the source text mentions "L'Éclamation" which might be a misinterpretation), would fit perfectly within the Rose + Croix Salons' preference for religious and mystical themes, treated with idealized grace rather than gritty realism. These works, along with his intricate etchings like those for the Golden Legend, exemplify his commitment to symbolic meaning, refined craftsmanship, and an aesthetic rooted in historical ideals yet filtered through a distinctly Symbolist lens.

Artistic Circles: Collaboration and Context

Armand Point's career unfolded within a vibrant network of artistic relationships, encompassing influences, collaborations, and dialogue with contemporaries. His formal teachers, Auguste Herst and Fernand Cormon, provided foundational training. Key influences shaping his mature style included the theorist John Ruskin and Pre-Raphaelite painters like Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, alongside the towering figures of the Italian Renaissance, Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci.

His most significant collaboration was arguably with Joséphin Péladan in the context of the Salon de la Rose + Croix, placing him alongside other idealist Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff, Carlos Schwabe, and Jean Delville. While sometimes mentioned in connection with the Nabis group (perhaps due to shared interests in decorative arts or simplified forms, potentially linking him loosely to figures like Paul Sérusier or Maurice Denis), Point's primary allegiance and aesthetic were more closely aligned with the Rose + Croix's specific brand of esoteric Symbolism and Renaissance revivalism.

He maintained friendships and working relationships, such as the one noted with Numa François Guillaumet, who reportedly drew inspiration from Point's Symbolist approach. He also existed in a field with contemporaries exploring different facets of Symbolism or reacting against it. Figures like Roger Zola, mentioned as exhibiting alongside Point but leaning towards Realism, highlight the diversity within the broader artistic landscape. Point carved a distinct niche, differentiating himself through his specific blend of influences and his commitment to reviving historical techniques within a Symbolist framework.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Armand Point continued to pursue his artistic vision, remaining largely dedicated to the Symbolist and revivalist ideals he had embraced in the 1890s. He maintained his base in Marlotte, where the Atelier Haute-Claire continued its activities, though perhaps with less prominence than in its initial years. His work continued to be exhibited, and some pieces were acquired by the French state, indicating a degree of official recognition despite his position outside the burgeoning modernist mainstream represented by Fauvism, Cubism (led by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque), and subsequent movements.

Point remained committed to a vision of art rooted in beauty, craftsmanship, and spiritual depth, standing apart from the more radical formal experiments that came to dominate the early 20th century. He passed away in Naples, Italy, in 1932. His wish was to be buried near Marlotte, the site of his artistic community at Haute-Claire, underscoring his deep connection to the place where he had attempted to realize his integrated vision of art and life.

Armand Point's legacy resides in his unique contribution to the Symbolist movement. He stands out for his dedicated effort to synthesize the aesthetics of the Italian Renaissance and the Pre-Raphaelites within a Symbolist framework. His emphasis on meticulous craftsmanship, his exploration of mystical and mythological themes, and his attempt to bridge the gap between fine and applied arts through initiatives like the Atelier Haute-Claire mark him as a distinctive figure. While perhaps less famous than some of his contemporaries, his work offers a compelling example of the idealistic and often retrospective currents within late 19th and early 20th-century European art.

Conclusion: A Singular Symbolist Path

Armand Point navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time with a distinct vision. From his early Orientalist depictions to his mature Symbolist works steeped in Renaissance and Pre-Raphaelite influences, he pursued an art of idealized beauty, technical refinement, and profound meaning. As a co-founder of the Salon de la Rose + Croix and the driving force behind the Atelier Haute-Claire, he actively sought to shape an artistic environment aligned with his anti-materialist and craft-focused principles. His paintings, engravings, and designs remain as testaments to a singular artistic journey, one that looked to the past to forge a deeply personal and spiritually resonant form of modern expression within the Symbolist movement. His work continues to attract interest for its unique blend of historical reverence and fin-de-siècle sensibility.