Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy stands as one of the most influential figures in 19th-century Russian art. A painter of remarkable skill, a penetrating art critic, and a dedicated organizer, Kramskoy was instrumental in shaping the course of Russian realism and fostering a democratic spirit within the artistic community. His life and work reflect the profound social and intellectual currents of his time, leaving an indelible mark on Russia's cultural heritage.

Early Life and Formative Years

Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy was born on May 27 (June 8, New Style), 1837, in the small town of Ostrogozhsk, Voronezh Governorate, into a modest petty-bourgeois family. His early life was marked by financial hardship, compelling him to seek work from a young age to support his family. This early exposure to the struggles of ordinary people would later inform his artistic sensibilities and his commitment to an art form rooted in social reality.

Kramskoy's artistic inclinations manifested early. By the age of fifteen, he was working as an apprentice to an icon painter, a traditional starting point for many Russian artists. A year later, at sixteen, he found employment as a retoucher in a photography studio. This experience with photography, a medium increasingly popular for its verisimilitude, likely honed his eye for detail and his appreciation for accurate representation, qualities that would become hallmarks of his mature painting style.

Despite his humble beginnings and lack of formal early training, Kramskoy harbored ambitions for a more profound artistic education. In 1857, through a fortunate turn of events and sheer determination, he managed to gain admission to the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. This institution, the bastion of artistic training in Russia, was steeped in Neoclassical traditions, emphasizing mythological, biblical, and historical subjects rendered in an idealized manner.

The Academy and the "Revolt of the Fourteen"

At the Imperial Academy of Arts, Kramskoy proved to be a talented student. However, he grew increasingly disillusioned with the institution's rigid academicism and its detachment from contemporary Russian life. The Academy's curriculum, heavily influenced by Western European models, often seemed irrelevant to the pressing social and moral questions that preoccupied the Russian intelligentsia of the mid-19th century. This was a period of significant social ferment, culminating in the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, and a growing desire among progressive circles for art that reflected national identity and addressed societal concerns.

Kramskoy became a leading voice among a group of students who advocated for greater artistic freedom and a more relevant curriculum. The simmering discontent came to a head in 1863. The Academy announced the theme for the annual Gold Medal competition – "The Feast of the Gods in Valhalla" – a subject from Norse mythology that felt utterly alien to Kramskoy and his like-minded peers. They petitioned the Academy to allow them to choose their own subjects, reflecting their desire to engage with themes closer to Russian reality.

When their request was denied, Kramskoy and thirteen other graduating students, in a bold act of defiance known as the "Revolt of the Fourteen," refused to participate in the competition and collectively withdrew from the Academy. This event was a watershed moment in Russian art history, signaling a decisive break with the old academic order and paving the way for a new, independent artistic movement. Among those who left with Kramskoy were figures who would also contribute to the changing landscape of Russian art, though Kramskoy emerged as the intellectual leader of this rebellion.

The Artel of Artists: A Precursor to a Movement

Following their departure from the Academy, Kramskoy and his fellow dissenters faced an uncertain future. To support themselves and continue their artistic pursuits independently, they formed the St. Petersburg Artel of Artists (Artel Khudozhnikov) in 1863. This was a cooperative association, a commune of sorts, where artists lived and worked together, sharing resources and commissions. The Artel was an innovative model for its time, embodying principles of mutual support and artistic independence.

Kramskoy was the driving force behind the Artel, its chief organizer and ideologue. The Artel undertook various commissions, including portraits and decorative work, to sustain its members. It also provided a space for intellectual exchange and the development of shared artistic principles. While the Artel itself was relatively short-lived, dissolving in 1871, it served as a crucial stepping stone towards a more organized and widespread movement. It demonstrated the viability of an artistic practice outside the confines of the Academy and laid the groundwork for the Peredvizhniki.

During this period, Kramskoy also began to teach at the Drawing School of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists from 1863 to 1868. This role allowed him to influence a younger generation of artists, instilling in them the values of realism and social consciousness that he championed.

The Peredvizhniki: Forging a National Art

The most significant of Kramskoy's organizational achievements was his role in the founding of the "Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions" (Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok), commonly known as the Peredvizhniki or "The Wanderers" (or "Itinerants"). Established in 1870, with its first exhibition in 1871, the Peredvizhniki became the dominant force in Russian art for several decades. Kramskoy was not only a co-founder but also its undisputed intellectual and spiritual leader.

The Peredvizhniki aimed to liberate Russian art from the control of the Academy and the aristocracy, making it accessible to a broader public across the vast Russian Empire. They organized travelling exhibitions that brought art to provincial towns, fostering a national appreciation for contemporary Russian art. Ideologically, the movement was committed to realism, depicting the lives of ordinary Russians, the beauty of the Russian landscape, and critical portrayals of social injustices. They believed art should serve a social purpose, educate, and inspire moral reflection.

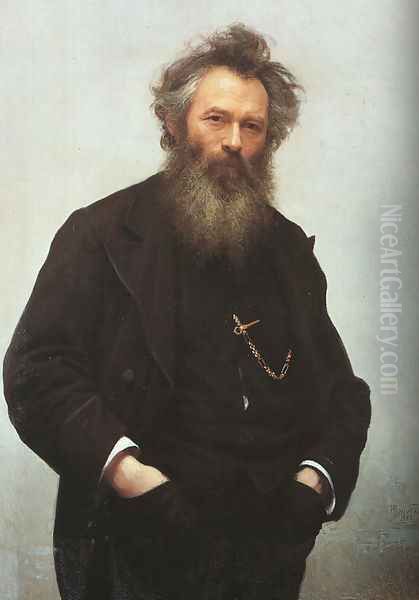

Kramskoy's leadership was pivotal. He articulated the movement's aesthetic and ethical principles, fostered a sense of camaraderie among its members, and tirelessly promoted their work. The Peredvizhniki included many of the most celebrated names in Russian art. Among its prominent members were Ilya Repin, renowned for his powerful historical canvases and portraits; Vasily Surikov, master of large-scale historical epics; Vasily Perov, a poignant chronicler of urban poverty and social critique; Ivan Shishkin, the "poet of the Russian forest"; Alexei Savrasov, whose lyrical landscapes captured the soul of Russia; and Nikolai Ge, whose historical and religious paintings were imbued with profound moral drama.

Other notable artists associated with the Peredvizhniki, either as founding members or later participants, included Grigory Myasoyedov (another key co-founder), Vladimir Makovsky, Konstantin Savitsky, Arkhip Kuindzhi, Viktor Vasnetsov (who later turned to mythological themes), Isaac Levitan (a master of the "mood landscape"), and Vasily Polenov. Kramskoy's ability to unite such diverse talents under a common banner speaks to his vision and influence. He maintained extensive correspondence with many of these artists, offering guidance, criticism, and encouragement.

Kramskoy's Artistic Philosophy and Critical Voice

Beyond his organizational efforts, Kramskoy was a profound art theorist and critic. He believed passionately in the social responsibility of the artist and the power of art to effect change. He advocated for an art that was truthful, deeply national, and imbued with high moral ideals. He was a staunch opponent of "art for art's sake," viewing it as a decadent and socially irresponsible pursuit. For Kramskoy, art was inextricably linked to life, and its highest calling was to reflect and interpret the human condition and the realities of Russian society.

His critical writings, often in the form of letters and articles, reveal a keen intellect and a deep understanding of artistic principles. He championed democratic ideals in art, arguing that it should be accessible and meaningful to the common people, not just a privileged elite. His ideas were closely aligned with the progressive intellectual currents of his time, influenced by writers and thinkers like Vissarion Belinsky, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, and Nikolai Dobrolyubov, who called for literature and art to serve the cause of social progress.

Kramskoy's aesthetic was rooted in realism, but it was a realism infused with psychological depth and moral earnestness. He believed that a true artist must not only depict external reality accurately but also penetrate the inner world of their subjects, revealing their thoughts, emotions, and spiritual struggles. This emphasis on psychological insight is particularly evident in his portraiture.

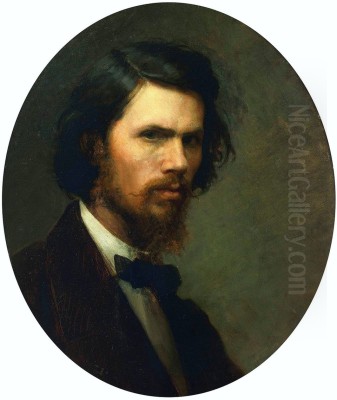

Master of Portraiture

Ivan Kramskoy is widely regarded as one of Russia's greatest portrait painters. His portraits are celebrated for their unflinching realism, their profound psychological penetration, and their ability to capture the sitter's essential character. He painted many of the leading cultural figures of his era, creating a veritable gallery of the Russian intelligentsia.

His approach to portraiture was meticulous. He sought not merely a likeness but an revelation of the individual's inner life, their intellectual and moral stature. His portraits often feature a restrained color palette and a focus on the face and hands, which he considered key to expressing character. The backgrounds are typically simple, ensuring that nothing distracts from the sitter's presence.

Among his most famous portraits is that of Leo Tolstoy (1873). Kramskoy depicted the great writer with an intense, searching gaze, capturing his intellectual power and moral authority. He also painted a striking portrait of the landscape painter Ivan Shishkin (1873, and another in 1880), conveying his robust personality and deep connection to nature. His portrait of the poet Nikolai Nekrasov (Nekrasov during the "Last Songs" period, 1877-1878) is a poignant depiction of the writer in his final illness, imbued with a sense of tragic dignity. Other notable sitters included the writer Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, the collector Pavel Tretyakov (founder of the Tretyakov Gallery), and the democratic critic Dmitry Pisarev. Each portrait is a testament to Kramskoy's ability to engage with his sitters on a deep intellectual and emotional level.

Key Thematic Works

While renowned for his portraits, Kramskoy also created a number of significant thematic paintings that explored religious, historical, and social issues. These works reflect his profound engagement with the moral and spiritual questions of his time.

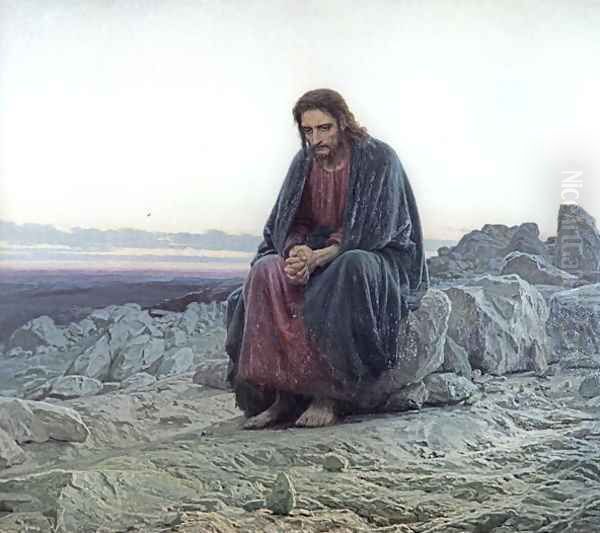

Christ in the Wilderness (1872)

Perhaps Kramskoy's most famous thematic work is Christ in the Wilderness (also known as Christ in the Desert). Completed in 1872 after years of contemplation and numerous studies, the painting depicts Christ seated alone in a barren, rocky landscape, his hands clasped, his gaze introspective and filled with sorrow. It portrays the moment of Christ's temptation in the desert, focusing on his internal struggle and profound human suffering.

The painting was a sensation when it was first exhibited. It broke with traditional, idealized representations of Christ, presenting him as a deeply human figure grappling with doubt and a momentous choice. Kramskoy himself described the work as an exploration of the moral dilemma faced by every individual at a crossroads in life. The starkness of the landscape mirrors Christ's isolation and the gravity of his spiritual ordeal. The work resonated deeply with the Russian intelligentsia, who saw in it a reflection of their own moral and philosophical quests. Artists like Nikolai Ge had also explored Christ's humanity, but Kramskoy's version had a particular psychological intensity that captivated his contemporaries. Pavel Tretyakov immediately acquired it for his collection.

Portrait of an Unknown Woman (1883)

Another iconic work is Portrait of an Unknown Woman (often referred to in English as An Unknown Woman or The Unknown Lady), painted in 1883. This captivating portrait depicts a stylishly dressed young woman in an open carriage, her gaze direct and somewhat haughty. The identity of the sitter has never been definitively established, adding to the painting's mystique.

The work generated considerable discussion and controversy. Some critics saw in her a symbol of the modern, independent woman, while others interpreted her as a "fallen woman" or a kept mistress, judging her by the societal norms of the time. Regardless of interpretation, the painting is a masterpiece of technique, showcasing Kramskoy's skill in rendering textures – the velvet of her coat, the feathers in her hat, the crisp winter air. The woman's enigmatic expression and confident demeanor challenge the viewer, making it one of the most memorable and debated images in Russian art. It has been compared to works like Édouard Manet's Olympia in its modernity and its capacity to provoke.

Inconsolable Grief (1884)

A deeply personal and moving work is Inconsolable Grief, painted in 1884. It depicts a woman dressed in mourning, her face etched with profound sorrow, standing beside a floral tribute, presumably at a graveside. The painting was created following the death of Kramskoy's own young son, and it channels his personal anguish into a universal expression of loss and bereavement. The restrained palette and the figure's dignified yet utterly devastated posture convey the depth of her suffering with immense emotional power. This work stands as a testament to Kramskoy's ability to translate profound human emotion onto canvas.

Other Notable Works

Kramskoy's oeuvre includes other significant paintings. Mermaids (or Rusalki, 1871) draws on Slavic folklore, depicting ethereal figures by a moonlit lake, showcasing a more romantic and poetic side of his art, perhaps influenced by the literary works of Nikolai Gogol. Forester (1874) is a strong character study of a rugged, self-reliant man of the woods, embodying a certain Russian archetype. Peasant with a Bridle (1883, also known as Mina Moiseyev) is another powerful depiction of a peasant, capturing his weathered dignity and resilience, a theme central to the Peredvizhniki ethos. His earlier work, Old Man with a Crutch (likely referring to Mina Moiseyev or a similar study), also highlights his focus on the character and dignity of ordinary rural folk.

Later Years and Untimely Death

Kramskoy remained a central figure in the Russian art world throughout his life. He continued to paint, write, and actively participate in the affairs of the Peredvizhniki. His influence extended to younger artists, including Valentin Serov, who would become a leading portraitist of the next generation, and Mikhail Vrubel, though Vrubel's Symbolist path diverged significantly from Kramskoy's realism.

Despite his artistic success and influence, Kramskoy's life was not without its struggles. He worked tirelessly, often at the expense of his health, driven by his artistic commitments and the need to support his family. The demands of portrait commissions, while providing income, could also be draining.

Ivan Kramskoy's life was cut short. On March 24 (April 5, New Style), 1887, while working on a portrait of Dr. Rauchfuss, a well-known St. Petersburg pediatrician, Kramskoy suddenly collapsed at his easel and died. He was only 49 years old. His death was a significant loss to Russian art and to the Peredvizhniki movement, which he had done so much to shape and sustain.

Legacy and Influence

Ivan Kramskoy's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. As a painter, he created some of the most iconic portraits and thematic works in Russian art, characterized by their psychological depth, technical mastery, and moral seriousness. His Christ in the Wilderness and Portrait of an Unknown Woman remain touchstones of Russian visual culture.

As an organizer and ideologue, he was the driving force behind the Peredvizhniki, a movement that fundamentally transformed Russian art. He helped to democratize art, making it accessible to a wider public and fostering a national school of painting rooted in Russian life and concerns. The Peredvizhniki, under his intellectual guidance, championed realism and social consciousness, influencing generations of Russian artists, including those who would later explore different artistic paths, such as Isaac Levitan, whose landscapes, while deeply personal, grew from the Peredvizhniki tradition. Even artists who eventually broke away to form groups like the "World of Art" (Mir Iskusstva), such as Alexandre Benois and Konstantin Somov, did so in dialogue with, or reaction to, the legacy of the Peredvizhniki.

As an art critic and theorist, Kramskoy articulated a compelling vision of art's social and moral purpose. His writings provide invaluable insights into the artistic debates of his time and continue to be studied for their clarity and conviction. He championed an art that was not merely aesthetically pleasing but also intellectually stimulating and ethically engaged.

Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy was more than just a talented artist; he was a cultural leader who profoundly shaped the artistic landscape of 19th-century Russia. His commitment to realism, his deep humanism, and his unwavering belief in the power of art to reflect and transform society ensure his lasting importance in the annals of art history. His work continues to be admired for its artistic excellence and its profound engagement with the human spirit.