John Duncan (1866-1945) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of Scottish art. Born in Dundee, Scotland, on July 19, 1866, Duncan's artistic journey traversed the dynamic currents of late 19th and early 20th-century European art, yet he remained deeply rooted in the cultural and mythological heritage of his homeland. His primary contributions lie within the realms of Symbolism and the Celtic Revival, movements through which he sought to express profound spiritual and nationalistic themes. Duncan's distinctive graphic style, meticulous technique, and evocative subject matter carved a unique niche for him among his contemporaries, leaving a legacy of works that continue to intrigue and inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Duncan's formative years in Dundee, a bustling industrial city, provided the initial backdrop for his artistic inclinations. He began his formal art training at the Dundee School of Art. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he sought broader horizons, leading him to further studies. He attended the South Kensington School of Art in London, and later, the Antwerp Academy under Charles Verlat, a respected Belgian painter. This exposure to continental European art, particularly the burgeoning Symbolist movement, would prove crucial in shaping his artistic vision.

His early career saw him working as an illustrator in London for publications such as The Pall Mall Budget and The Strand Magazine. This experience in illustration likely honed his strong sense of line and composition, characteristics that would become hallmarks of his mature painting style. However, it was his return to Scotland and his immersion in its cultural renaissance that truly defined his artistic path.

The Celtic Revival and Duncan's Vision

The late 19th century witnessed a burgeoning interest in Celtic culture, mythology, and identity across Britain and Ireland, a movement known as the Celtic Revival. In Scotland, this took on a particular fervour, with artists and intellectuals seeking to rediscover and celebrate a distinct national heritage. John Duncan became a pivotal figure in the visual arts arm of this movement. He was closely associated with the polymath Sir Patrick Geddes, a biologist, sociologist, and town planner who was a key proponent of cultural renewal in Edinburgh.

Duncan contributed significantly to Geddes's periodical, The Evergreen, a literary and artistic magazine that served as a mouthpiece for the Celtic Revival in Scotland. His illustrations for The Evergreen showcased his developing style, blending mythological themes with a decorative, linear approach. He also undertook significant mural commissions for Geddes, most notably for Ramsay Garden in Edinburgh, where he depicted scenes from Scottish history and Celtic legend, populating them with heroic figures and mystical landscapes. These murals were instrumental in visually articulating the ideals of the Celtic Revival, aiming to inspire a sense of national pride and connection to a rich, ancient past. Other figures associated with the broader Celtic Revival, though perhaps in different artistic or literary spheres, include the Irish poet W.B. Yeats and the writer George William Russell (Æ), whose work similarly drew on Celtic mythology and spirituality.

Symbolism: The Language of the Soul

Parallel to his engagement with the Celtic Revival, John Duncan was deeply influenced by European Symbolism. This late 19th-century art movement reacted against Naturalism and Realism, favouring instead the expression of ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery and symbolic meaning. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in France, or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, sought to evoke rather than describe, creating dreamlike and often enigmatic compositions.

Duncan absorbed these influences, particularly from French Symbolists such as Alexandre Séon, whose work he would have encountered. He adapted Symbolist principles to his own artistic concerns, using them to explore themes of mysticism, spirituality, the supernatural, and the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth. His paintings are often imbued with a sense of otherworldliness, populated by ethereal figures, mythical creatures, and landscapes that seem to exist beyond the realm of ordinary experience. The meticulous detail and often jewel-like colours in his work further enhance this sense of preciousness and spiritual significance.

Key Themes and Motifs in Duncan's Art

Duncan's oeuvre is rich with recurring themes and motifs, drawn primarily from Celtic mythology, Arthurian legend, biblical stories, and classical antiquity, all filtered through a Symbolist lens. He was particularly drawn to figures and narratives that embodied spiritual quests, heroic ideals, or moments of mystical revelation.

Celtic mythology provided a fertile ground for his imagination. Figures such as Cuchulainn, Ossian, Deirdre, and various Celtic deities and heroes populate his canvases. He was fascinated by the tales of the Fianna, the legendary band of warriors led by Fionn mac Cumhaill, and the mystical realm of Tír na nÓg, the land of eternal youth. These stories allowed him to explore themes of heroism, sacrifice, love, and the enduring power of the Celtic spirit.

Arthurian legends also captured his interest, offering another rich vein of chivalric and mystical narratives. The quest for the Holy Grail, the figures of King Arthur, Merlin, and the knights of the Round Table, resonated with Symbolist preoccupations with spiritual journeys and hidden truths.

Biblical subjects were approached not merely as illustrations of scripture but as opportunities to explore deeper spiritual meanings. His depictions often emphasize the mystical or visionary aspects of these stories. Similarly, his engagement with classical mythology, such as the myths of ancient Greece and Egypt, was selective, focusing on narratives that lent themselves to symbolic interpretation.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of John Duncan's paintings stand out as iconic representations of his artistic vision and technical skill.

Anima Celtica (1895), now in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland, is one of his most celebrated works. The title itself, meaning "Celtic Soul," encapsulates the painting's ambition. It depicts a serene, androgynous female figure, a personification of the Celtic spirit, standing amidst a symbolic landscape. She holds a sprig of mistletoe, a plant sacred to the Druids, and is surrounded by symbols of regeneration and the cyclical nature of life. The painting's flat, decorative style, precise linearity, and subtle colour harmonies are characteristic of Duncan's mature work and reflect the influence of both Symbolism and Art Nouveau aesthetics. It is a powerful visual statement of cultural identity and spiritual resilience.

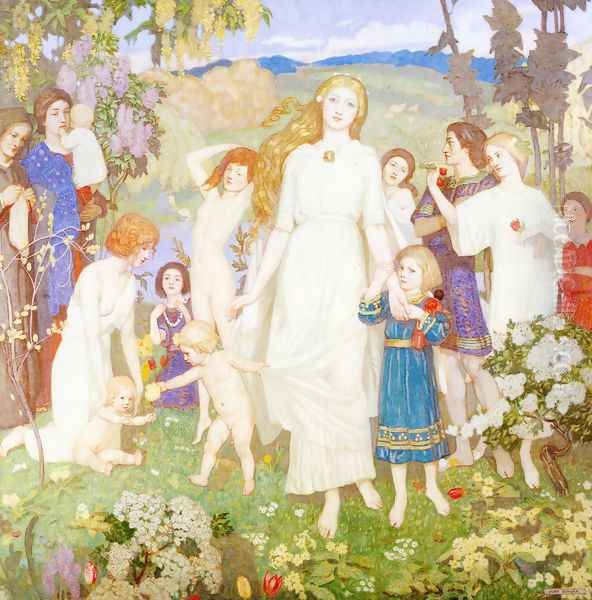

St Bride (1913), also in the National Galleries of Scotland, is another key work. St. Brigid of Kildare (or St. Bride) is a revered figure in Celtic Christianity, often associated with the ancient Celtic goddess Brigid. Duncan portrays her as a gentle, luminous figure, accompanied by angels and symbolic animals, arriving by boat to the shores of Scotland. The scene is imbued with a sense of peace and divine grace. The painting reflects Duncan's interest in the syncretism of pagan and Christian traditions within Celtic culture and highlights the diverse strands of Scottish identity. The meticulous rendering of details, from the saint's flowing robes to the delicate flora, showcases his refined technique.

The Ramsay House Murals (circa 1890s), though perhaps less widely known than his easel paintings, were significant public works. Commissioned by Patrick Geddes for his Outlook Tower and Ramsay Garden complex in Edinburgh, these murals depicted heroic figures and pivotal moments from Scottish history and Celtic mythology. They were intended to be didactic, fostering a sense_of national consciousness and cultural pride among the students and residents who viewed them. These works demonstrate Duncan's ability to work on a large scale and to integrate his artistic vision with architectural spaces.

Tristan and Isolde (1912) tackles one of the great romantic and tragic legends of Celtic origin. Duncan's interpretation focuses on the mystical and fated nature of their love, often emphasizing the dreamlike or otherworldly quality of their encounters. His depiction avoids melodrama, instead imbuing the scene with a quiet intensity and symbolic resonance, characteristic of his Symbolist approach.

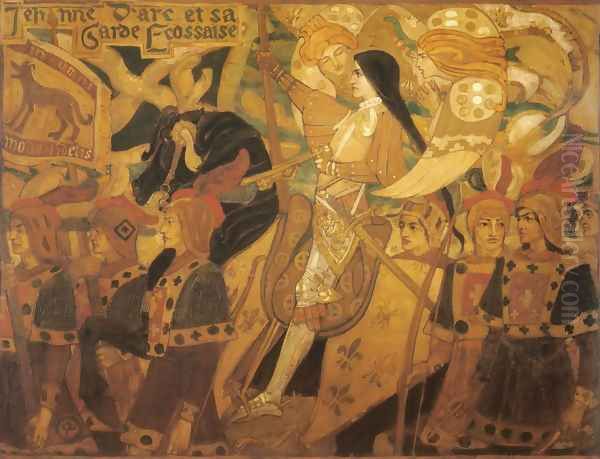

Jehanne d’Arc et sa Garde Écossaise (Joan of Arc and her Scottish Guard) is another notable painting that highlights the historical links between Scotland and France, a theme that resonated with the Auld Alliance. It combines historical subject matter with Duncan's characteristic spiritual and symbolic overtones, portraying Joan not just as a military leader but as a divinely inspired figure.

His watercolour Head of Ossian, in the collection of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture, demonstrates his skill in a different medium, capturing the melancholic and visionary character of the legendary Celtic bard.

Technique, Style, and Influences

John Duncan's artistic style is highly distinctive. He often worked in tempera, a medium favoured by early Renaissance painters and some Symbolists for its capacity to produce clear, luminous colours and a smooth, matte finish. This choice of medium contributed to the precise, linear quality of his work. His compositions are often carefully structured, with a strong emphasis on pattern and decorative elements, aligning him with aspects of the Art Nouveau movement, which was flourishing concurrently. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley in Britain, with his highly stylized black and white illustrations, or Gustav Klimt in Vienna, with his ornate, gilded surfaces, shared this interest in decorative linearity, though their subject matter and overall aesthetic differed.

Duncan's figures are typically elongated and graceful, possessing an ethereal, almost otherworldly quality. They often appear contemplative or entranced, their gestures and expressions conveying inner states rather than overt action. His use of colour is subtle and harmonious, often employing a palette of blues, greens, and muted earth tones, punctuated by brighter accents that draw attention to symbolic details.

The influence of early Italian Renaissance painters, such as Sandro Botticelli or Fra Angelico, can be discerned in the clarity of his forms, the lyrical quality of his lines, and the spiritual intensity of his figures. This connection to earlier art traditions was common among Symbolist painters, who often looked to pre-Realist art for inspiration. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Britain, including artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, had earlier championed a return to the sincerity and detailed naturalism of art before Raphael, and while Duncan's style was more stylized and less naturalistic than the core Pre-Raphaelites, he shared their interest in literary, mythological, and medieval subjects, as well as their meticulous approach to execution.

His graphical style, likely honed during his time as an illustrator, set his paintings apart from many of his Scottish contemporaries. While artists like the "Glasgow Boys" (e.g., James Guthrie, Sir John Lavery) were exploring Realism and Impressionism, and later the "Scottish Colourists" (S.J. Peploe, F.C. Cadell, Leslie Hunter, and J.D. Fergusson) were embracing the bold palettes of French Fauvism and Post-Impressionism, Duncan pursued a more introspective and symbolic path, focusing on line, intricate detail, and narrative depth. However, he was not entirely isolated; the Glasgow School also included figures like Charles Rennie Mackintosh and "The Four" (Mackintosh, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Frances Macdonald MacNair, and James Herbert MacNair), whose distinctive Art Nouveau style, with its emphasis on elongated forms and symbolic decoration, shared some affinities with Duncan's aesthetic.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

John Duncan was an active participant in the cultural life of Scotland, particularly in Edinburgh. His collaboration with Patrick Geddes was central to his involvement in the Celtic Revival. Geddes's vision of cultural renewal provided an intellectual framework and practical opportunities for Duncan's art. Through Geddes, Duncan connected with other writers, artists, and thinkers who shared similar ideals.

He also collaborated with the writer William Sharp, who wrote under the pseudonym Fiona MacLeod. Sharp/MacLeod was a key literary figure in the Celtic Revival, producing mystical tales and poems steeped in Celtic folklore. Their collaborations, often involving Duncan's illustrations for MacLeod's texts, aimed to create a synthesis of visual art and literature that would powerfully evoke the spirit of the Celtic world. The singer Marjory Kennedy-Fraser, who collected and popularized Hebridean folk songs, was another contemporary with whom Duncan shared a cultural affinity, both working to preserve and celebrate Scotland's Gaelic heritage.

While his style differed from many of his Scottish peers, he was part of a broader European artistic environment where Symbolism and Art Nouveau were significant forces. His work can be seen in dialogue with international Symbolists, and his commitment to national themes paralleled similar movements in other European countries, where artists sought to define and express their unique cultural identities in the face of industrialization and cultural homogenization.

Later Career and Legacy

John Duncan continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, remaining committed to his distinctive style and thematic concerns. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA) in 1910 and a full Royal Scottish Academician (RSA) in 1923, indicating the recognition he received from the Scottish artistic establishment.

His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Scottish artists who have explored themes of myth, legend, and national identity. While the overtly Symbolist style he championed may have waned in popularity with the rise of Modernism in the mid-20th century, there has been a renewed appreciation for his work in recent decades, as art historians and the public have rediscovered the richness and complexity of late 19th and early 20th-century art beyond the dominant modernist narratives.

Duncan's dedication to the Celtic Revival contributed significantly to the visual culture of that movement, providing enduring images that helped to shape a modern understanding of Celtic identity. His work serves as a reminder of the power of art to explore spiritual and mythological themes, and to connect with deep-seated cultural traditions.

John Duncan's Works in Collections and the Art Market

Today, John Duncan's works are held in several important public collections, primarily in Scotland. The National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh holds key pieces like Anima Celtica and St Bride, making them accessible to a wide audience. The Wardlaw Museum at the University of St Andrews houses his painting Mary Queen of Scots at Fotheringay. The Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture in Edinburgh also holds works, including the watercolour Head of Ossian.

His works also appear on the art market, though perhaps less frequently than those of some of his more commercially-oriented contemporaries. Paintings such as Woodcock (Just Arrived) and Blonde in the South have appeared at auction houses like Lyon & Turnbull in Glasgow. The fate of some of his larger mural works, such as those created for school halls, has sometimes been precarious, with instances of them being removed and restored, their future placement or sale subject to various considerations, as was the case with murals temporarily stored at the Gillis Centre. The presence of his work in both public collections and the auction market attests to his enduring, if specialized, appeal and historical significance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Scottish Voice

John Duncan was an artist of singular vision and purpose. In an era of rapid artistic change, he forged a distinctive path, drawing inspiration from the rich tapestry of Celtic mythology, the spiritual explorations of Symbolism, and the decorative elegance of Art Nouveau. His commitment to the Celtic Revival provided Scotland with a powerful visual language for its cultural aspirations, creating images that continue to resonate with a sense of national identity and mystical allure.

His meticulous technique, often employing tempera to achieve luminous, jewel-like effects, and his strong, graphic style, set him apart. While he may not have achieved the widespread international fame of some avant-garde figures, his contribution to Scottish art and to the broader Symbolist movement is undeniable. Through works like Anima Celtica and St Bride, John Duncan left an indelible mark, offering a profound and beautifully rendered vision of Scotland's soul and its enduring connection to a mythic past. His art invites viewers to look beyond the surface of reality, into a realm of dreams, legends, and spiritual truths, making him a compelling and important figure in the history of art.