Introduction: An Artist Bridging Worlds

Daniel Maclise stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British and Irish art. Born in Cork, Ireland, in 1806, he rose to prominence within the London art establishment, becoming a celebrated painter of historical narratives, literary scenes, and striking portraits. His career unfolded during the heart of the Victorian era, a time of immense industrial change, social upheaval, and burgeoning national identity, all of which found reflection in the art of the period. Maclise navigated the complex currents of artistic taste, achieving considerable fame and official recognition, yet his legacy remains multifaceted, positioned between the artistic traditions of his native Ireland and the dominant trends of the British capital. He was a masterful draughtsman and a storyteller in paint, capturing the drama of the past and the personalities of his illustrious contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Cork

Daniel Maclise's journey began in Cork City on January 25, 1806. His background was modest; his father, Alexander Maclise, was a Scotsman, formerly a soldier in the Elgin Fencibles, who later worked as a tanner or shoemaker in Cork. His mother, Rebecca Buchanan, was Irish. This mixed heritage perhaps foreshadowed the artist's later career, which would be deeply connected to both Ireland and Britain. From an early age, Daniel displayed a clear aptitude for drawing, an inclination that was encouraged despite the family's limited means. His formal artistic education commenced at the Cork School of Art, also known as the Cork Institute, around 1822.

The Cork School of Art, established shortly before Maclise enrolled, provided foundational training. One of his instructors there was Mr. Chalmers, noted as an assistant scene painter at the local theatre. This early exposure to theatricality might have influenced Maclise's later penchant for dramatic compositions and historical staging. Even in these formative years, his talent was evident. A pivotal moment came in 1825 when the renowned novelist Sir Walter Scott visited Cork. The young Maclise seized the opportunity to sketch Scott in a bookshop, creating a likeness so successful that it was lithographed and sold widely, bringing the budding artist his first taste of public recognition. This early success, combined with his ambition, fueled his desire to pursue art in the larger centre of London.

London Calling: The Royal Academy Schools

Around 1827, supported by local patrons impressed by his talent, Daniel Maclise moved to London to further his artistic education. He enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1828. This institution was the epicentre of the British art world, presided over by figures like Sir Thomas Lawrence at the time of Maclise's arrival, and later Sir Martin Archer Shee. Admission and success here were crucial steps for any aspiring artist seeking establishment recognition. Maclise quickly distinguished himself among his peers, demonstrating exceptional skill, particularly in drawing.

His progress through the Academy Schools was marked by numerous accolades. He won the silver medal for drawing from the antique and later for drawing from the life model. His crowning achievement as a student came in 1831 when he was awarded the gold medal for historical composition for his painting The Choice of Hercules. This success signalled his ambition to excel in history painting, considered the highest genre of art at the time, following in the footsteps of earlier British masters, though the genre faced challenges in securing patronage compared to portraiture or landscape. Maclise's technical proficiency and dedication set him apart, laying the groundwork for a successful professional career.

Rise to Prominence: The Royal Academy and Early Success

Following his triumphs at the Academy Schools, Maclise began exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. His works quickly attracted attention for their technical brilliance, intricate detail, and often dramatic or literary subjects. Paintings like Mokanna Unveiling his Features to Zelica (1833), inspired by Thomas Moore's Lalla Rookh, and The Installation of Captain Rock (1834), depicting Irish agrarian unrest, showcased his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and engage with both romantic literature and contemporary social themes.

His growing reputation led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1835, a significant mark of recognition from his peers. Just five years later, in 1840, he achieved the status of full Royal Academician (RA), solidifying his position within the art establishment. This rapid ascent was a testament to his talent and the appeal of his work to Victorian audiences. He became known for his meticulous finish and crowded canvases, filled with carefully rendered details of costume, architecture, and human expression, characteristics that resonated with the era's taste for narrative clarity and visual richness. His contemporaries at the Academy included established figures like J.M.W. Turner and rising stars such as Edwin Landseer.

Master of Illustration: Fraser's and Dickens

Alongside his burgeoning career as a painter, Maclise established himself as one of the foremost illustrators of his day. His skill as a draughtsman was particularly suited to the burgeoning market for illustrated books and periodicals. Between 1830 and 1838, he contributed a remarkable series of portrait sketches to Fraser's Magazine, under the pseudonym 'Alfred Croquis'. This "Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters" featured witty and incisive caricatures of the leading writers, artists, and public figures of the time, including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Charles Lamb. These drawings, often dashed off with remarkable speed and accuracy, cemented his reputation for capturing likeness and character.

Perhaps Maclise's most famous literary connection was his close friendship with the novelist Charles Dickens. The two met in the mid-1830s and formed a strong bond, socialising frequently and travelling together. Maclise became part of Dickens's circle, which included figures like John Forster (Dickens's biographer, whom Maclise also painted) and fellow artists like Clarkson Stanfield. Maclise provided illustrations for several of Dickens's Christmas Books, including The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), and The Battle of Life (1846). He also drew the famous frontispiece portrait of Dickens for Nicholas Nickleby. His illustrative style, precise and expressive, complemented Dickens's vivid prose, though he worked alongside other prominent illustrators of Dickens's work, such as George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). Their friendship, though close for many years (Maclise was godfather to Dickens's son Walter), eventually cooled, possibly due to personal strains or the pressures of their demanding careers.

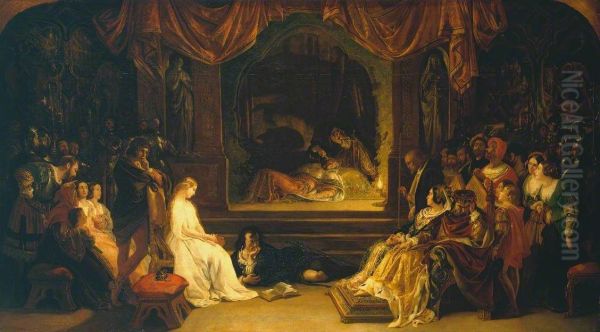

History Painting on a Grand Scale: Strongbow and Aoife

Maclise harboured ambitions to succeed in history painting, a field notoriously difficult for British artists, as exemplified by the struggles of Benjamin Robert Haydon. Maclise, however, achieved considerable success in this genre. One of his most significant historical works, particularly resonant with his Irish heritage, is The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife (1854). This enormous canvas, now housed in the National Gallery of Ireland, depicts the arranged marriage between the Norman warlord Richard de Clare (Strongbow) and Aoife, daughter of the King of Leinster, following the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1170.

The painting is a tour de force of historical reconstruction and dramatic composition. Maclise fills the scene, set amidst the ruins and aftermath of battle, with a vast array of figures – victorious Normans, defeated Irish warriors, grieving women, and watchful clergy. The level of detail in armour, costume, and physiognomy is astonishing, reflecting meticulous research. The work aimed to capture a pivotal, and controversial, moment in Irish history. Its reception was mixed, praised for its technical skill and ambition but also debated for its interpretation of the historical event. It remains one of Maclise's most debated works and a landmark painting in 19th-century Irish art, inviting comparisons with the earlier Irish history painter James Barry, whom Maclise admired.

The Westminster Frescoes: A Monumental Undertaking

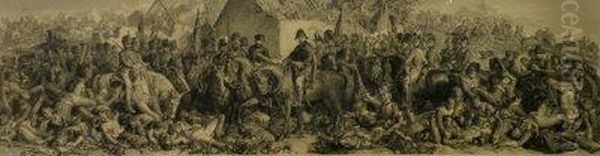

Maclise's ambition found its grandest stage in the 1840s and 1850s when he was commissioned to paint two enormous frescoes for the newly rebuilt Houses of Parliament at Westminster. This project, overseen by a Royal Commission headed by Prince Albert, aimed to decorate the Palace with scenes from British history, promoting national pride and artistic excellence. Maclise was tasked with depicting The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after the Battle of Waterloo and The Death of Nelson for the Royal Gallery. These were subjects central to British national identity and military glory.

The undertaking was immense and fraught with difficulty. Maclise devoted years to meticulous research, drawing countless preparatory studies. He chose to work in the waterglass (stereochromy) technique, a method developed in Germany intended to be more durable than true fresco in the damp British climate. However, the technique proved laborious and challenging. Maclise spent years, often working in isolation under difficult conditions, to complete these vast murals (each measuring about 45 feet long). The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher was completed in 1861, and The Death of Nelson in 1864.

The frescoes were hailed for their epic scale, narrative power, and incredible detail, solidifying Maclise's reputation as a leading history painter. They stand as monuments to Victorian ambition and artistic endeavour. However, the immense physical and mental strain took a heavy toll on Maclise. Furthermore, the waterglass technique ultimately proved unsuccessful in the long term, and the murals suffered from deterioration. Other artists involved in the Westminster decoration scheme included William Dyce and Edward Matthew Ward, who also faced technical challenges. Despite the difficulties, these works remain Maclise's most famous public commissions.

Portraiture and Society

While renowned for his history paintings and illustrations, Daniel Maclise was also an accomplished portrait painter. His ability to capture a likeness, evident from his early sketch of Sir Walter Scott, remained a constant throughout his career. He painted portraits of many prominent figures of his time, benefiting from his connections within London's literary and artistic circles. His sitters included fellow artists, writers like his friend Charles Dickens and John Forster, the actor William Macready (with whom he also collaborated on theatrical projects), and members of the aristocracy.

One notable commission was a portrait of Queen Victoria herself, painted at Buckingham Palace. This royal patronage further cemented his status within the establishment. His portrait style was generally characterized by careful detail and a strong sense of the sitter's presence, though perhaps lacking the psychological depth found in the work of some contemporaries. His portraits provide a valuable visual record of the key personalities who shaped the cultural landscape of Victorian Britain. His social life placed him at the heart of this world, attending dinners and gatherings where the artistic and literary elite mingled.

Artistic Style and Technique

Daniel Maclise's artistic style is distinctive and reflects the prevailing tastes of the Victorian era while retaining a personal signature. His work is characterized above all by exceptional draughtsmanship. His drawing is precise, detailed, and confident, forming the strong foundation upon which his paintings are built. This linear clarity is evident in both his finished paintings and his numerous preparatory sketches and illustrations. He favoured complex, often crowded compositions, meticulously arranging large numbers of figures into coherent narrative scenes.

His attention to detail was legendary, extending to costume, architecture, and accessories, all rendered with painstaking accuracy based on thorough research. This aligns with the Victorian appreciation for realism and historical veracity. However, his work also possesses a strong element of romanticism and theatricality, evident in the dramatic gestures, expressive faces, and carefully staged lighting of his scenes. His colour palette could be rich and vibrant, though sometimes criticized by contemporaries for being harsh or lacking atmospheric subtlety compared to artists like Turner.

While Maclise worked during the rise of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (founded 1848), whose members like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt also emphasized detail and literary subjects, Maclise's style remained distinct. He did not share their embrace of intense, jewel-like colour or their specific medievalizing tendencies, adhering more closely to academic traditions of composition and finish, albeit infused with his own dramatic energy. His style was uniquely his own, a blend of academic discipline, romantic sensibility, and Victorian narrative drive.

Later Years and Legacy

The immense labour involved in the Westminster frescoes had a profound impact on Daniel Maclise's health and spirit. He emerged from the project exhausted and somewhat disillusioned. Although he continued to paint and exhibit, his output slowed in his later years. Friends observed that he became increasingly withdrawn and melancholic. The art world was also changing, with new movements and aesthetic ideas beginning to challenge the dominance of the academic style he represented.

In 1866, following the death of Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, Maclise was offered the Presidency of the Royal Academy, the highest honour in the British art establishment. However, he declined the position, citing his desire for privacy and retirement from public life. This refusal underscored his growing detachment from the official art world he had once conquered. His health continued to decline, and he died suddenly from acute pneumonia on April 25, 1870, at his home in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. His death was mourned by many in the art and literary worlds. His friend Charles Dickens, who himself would die only weeks later, gave a moving tribute at the Royal Academy banquet, praising Maclise's "great genius" and "modest, retiring disposition."

Daniel Maclise's legacy is that of a major figure in Victorian art, a bridge between Irish and British traditions. He excelled as a history painter on a grand scale, a sensitive portraitist, and a brilliant illustrator. His work captured the spirit of his age – its fascination with history, literature, national identity, and intricate detail. While his style fell out of fashion in the later 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise of Impressionism and Modernism, there has been a renewed appreciation for his technical skill, narrative power, and his significant contribution to the visual culture of Victorian Britain. His works, particularly the Westminster murals and The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife, remain important documents of 19th-century artistic ambition and cultural concerns.

Conclusion: A Victorian Master of Narrative Art

Daniel Maclise carved a unique path through the complex art world of the 19th century. From his beginnings in Cork to the heights of the London establishment and the monumental challenges of the Westminster Palace commissions, he pursued his vision with remarkable dedication and skill. As a painter of history, literature, and portraits, and as a master illustrator, he created a body of work that vividly reflects the tastes, ambitions, and anxieties of the Victorian era. His meticulous technique, dramatic compositions, and narrative clarity captivated audiences during his lifetime. While subject to the shifting tides of artistic fashion, his major works endure as powerful examples of Victorian academic art, and his illustrations, particularly the Fraser's portraits and his collaborations with Dickens, offer an intimate glimpse into the cultural life of his time. He remains a key figure for understanding the art and culture of both Ireland and Britain in the age of Victoria.