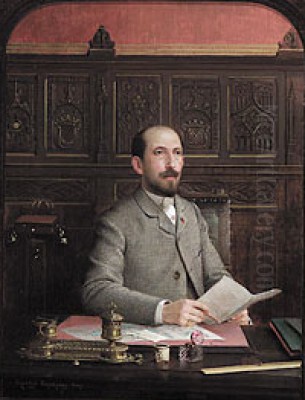

Georges Croegaert stands as a fascinating figure in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century European art. A Belgian painter who found fame and fortune in Paris, he carved a distinct niche for himself with his meticulously rendered canvases. He is celebrated for two primary genres: elegant portraits and interior scenes featuring fashionable women, and a unique series of humorous, often gently satirical, depictions of Roman Catholic cardinals enjoying worldly pleasures. His work, rooted in the academic tradition yet touched by contemporary influences, offers a window into the tastes, aspirations, and subtle social critiques of the Belle Époque.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Born in Antwerp, Belgium, on October 7, 1848, Georges Croegaert emerged from a city with a rich artistic heritage. Antwerp, once the home of giants like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, maintained a strong tradition of craftsmanship and painterly skill. Croegaert received his formal artistic training at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. This institution upheld the rigorous standards of academic art, emphasizing drawing, composition, and a high degree of finish, principles that would remain central to Croegaert's practice throughout his career.

During his formative years, Belgium was experiencing its own artistic currents. While the Academy promoted traditional values, the influence of Realism was also palpable. The French painter Gustave Courbet, a leading proponent of Realism, had lectured in Belgium, advocating for art that depicted the realities of modern life. While Croegaert would ultimately pursue a more polished and less overtly political style than Courbet, the emphasis on observable detail and contemporary subjects likely resonated with the young artist. His early works already demonstrated a keen eye for detail and a solid grounding in academic technique.

The Parisian Scene: A New Arena for Ambition

In 1876, seeking broader opportunities and exposure, Croegaert made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. At this time, Paris was unequivocally the capital of the Western art world, a vibrant hub of creativity, criticism, and commerce. It was the stage for the official Salon, the annual state-sponsored exhibition that could make or break an artist's reputation. Success at the Salon meant critical recognition, patronage, and access to a burgeoning market of collectors, both French and international.

Croegaert quickly adapted to the Parisian environment. He began exhibiting regularly at the Salon, showcasing works that appealed to the prevailing tastes of the time. His technical proficiency, honed in Antwerp, was immediately apparent. He also exhibited his work in other major European cities, including Brussels and Vienna, gradually building an international reputation. Paris provided not only a platform but also a rich source of inspiration, from the fashionable society that populated its salons and boulevards to the diverse artistic styles competing for attention.

The Painter of Elegance: Fashion and Finery

One significant facet of Croegaert's oeuvre involved the depiction of elegant women, often shown in luxurious domestic interiors. These paintings captured the aspirations and aesthetics of the prosperous bourgeoisie during the Belle Époque. His subjects are typically young, attractive women dressed in the height of fashion, adorned with silks, satins, lace, and jewels. They inhabit opulent rooms filled with plush furniture, intricate tapestries, gleaming objets d'art, and often, elements reflecting the contemporary fascination with exoticism.

Croegaert possessed an extraordinary talent for rendering textures. His depiction of fabrics, particularly silk and satin, was masterful. He captured the sheen, the folds, and the delicate interplay of light on these materials with remarkable verisimilitude. This technical virtuosity was highly prized by collectors. These works were not merely portraits but carefully constructed genre scenes, offering glimpses into a world of refined leisure and material comfort. In this focus on contemporary elegance and detailed interiors, his work bears comparison with fellow Belgian Alfred Stevens, also successful in Paris, and the French painter James Tissot, both known for chronicling the lives of the fashionable elite.

These paintings often feature solitary figures engaged in quiet activities – reading a letter, arranging flowers, contemplating a piece of art, or simply lost in thought. The settings are meticulously detailed, providing context and enhancing the narrative quality. Gilt-framed mirrors, ornate clocks, porcelain vases, and patterned wallpapers all contribute to the atmosphere of sophisticated domesticity. Croegaert's skill lay in balancing the detailed rendering of the environment with the psychological presence of the figure, creating scenes that were both visually sumptuous and subtly evocative.

The Cardinal Paintings: A Genre of Gentle Satire

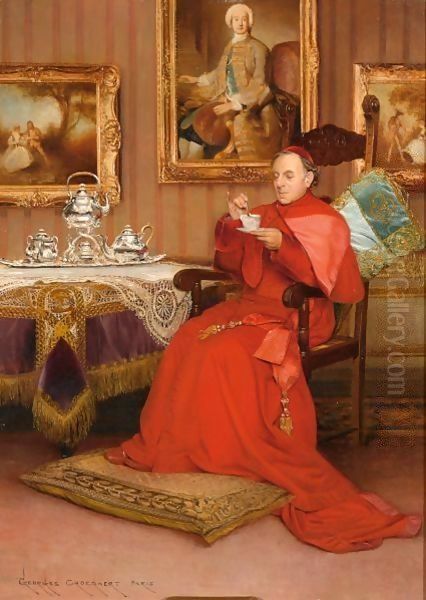

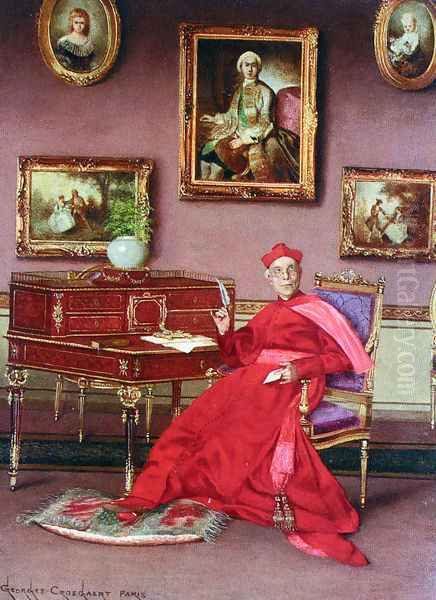

Perhaps Georges Croegaert's most distinctive contribution to art history is his series of paintings depicting Roman Catholic cardinals. These works, often referred to as "Cardinal Paintings" or "Anti-clerical Art," present high-ranking church officials in moments of private indulgence, far removed from their spiritual duties. Cardinals are shown enjoying fine meals, sampling wine, playing musical instruments, examining art objects, or engaging in leisurely hobbies within lavishly appointed chambers.

This genre found particular favor during the French Third Republic (1870-1940), a period marked by significant tension between the secular state and the Catholic Church. Anti-clerical sentiment was widespread, and art that gently mocked the perceived hypocrisy and worldliness of the clergy resonated with a segment of the public and the art market. Croegaert's approach was typically humorous rather than overtly condemnatory. The satire lies in the juxtaposition of the cardinals' religious vestments – the vibrant scarlet robes symbolizing their high office – with their very human, often mundane or self-indulgent, activities.

His cardinals are often portrayed as connoisseurs of good living, surrounded by the trappings of wealth: fine furniture, expensive food and drink, luxurious fabrics, and objets d'art. Works like Tea Time exemplify this theme, showing a cardinal comfortably settled for refreshments, the scene rendered with Croegaert's characteristic attention to detail and rich color. The humor often derives from the slightly comical poses, the expressions of contentment or concentration on worldly matters, and the sheer opulence of their surroundings.

Croegaert was not alone in exploring this theme. The French painter Jehan Georges Vibert (1840-1902) is perhaps the most famous exponent of the Cardinal Painting genre, known for his witty and sharply observed scenes of clerical life. Croegaert certainly operated within this established niche, alongside artists like Andrea Landini and François Brunerie, who also found success depicting cardinals in similarly humorous situations. Croegaert's contribution is marked by his exceptional technical skill and his slightly gentler, less biting tone compared to Vibert.

Artistic Style and Technical Mastery

Georges Croegaert's style remained fundamentally rooted in the academic tradition throughout his career. His work is characterized by meticulous draughtsmanship, smooth surfaces, and a high level of finish, often referred to as 'fini'. He paid extraordinary attention to detail, rendering textures, patterns, and objects with painstaking accuracy. This precision extended from the intricate lace on a lady's dress to the wood grain of a piece of furniture or the reflective surface of polished silver.

His palette was rich and vibrant. He demonstrated a particular fondness for strong, saturated colors, especially the deep reds of cardinal robes and the jewel tones of fashionable attire and luxurious upholstery. He skillfully used color and light to model form, create depth, and draw the viewer's eye to key elements within the composition. While fundamentally a realist in his detailed observation, some critics have noted subtle influences from Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and perhaps a slightly looser touch in less critical areas of the canvas, though he never embraced the broken brushwork or plein-air principles of the Impressionist movement led by figures like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Compositionally, Croegaert's paintings are carefully constructed. He arranged figures and objects to create balanced and harmonious scenes, often using interior architectural elements or furniture to frame the subject or lead the eye through the space. The narrative quality of his genre scenes is enhanced by his ability to place figures within believable, richly detailed environments that contribute to the story or mood. His skill was not just in rendering individual objects but in orchestrating them into a cohesive and visually engaging whole.

Japonisme's Subtle Influence

Like many artists working in Paris during the late nineteenth century, Georges Croegaert appears to have been touched by the prevailing trend of Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics. Following the opening of Japan to the West in the mid-19th century, Japanese prints (ukiyo-e), ceramics, textiles, fans, and decorative objects flooded European markets, profoundly influencing artists across various movements.

In Croegaert's paintings, particularly his interior scenes, elements of Japonisme often appear as decorative props. Japanese screens, porcelain vases, fans, or small figurines might be included in the background, reflecting the fashionable taste for exotic collectibles among the European elite. These objects add a layer of visual interest and contemporary relevance to his depictions of stylish interiors. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet integrated Japanese principles more deeply into their compositional strategies, but Croegaert's engagement seems primarily focused on incorporating Japanese artifacts as part of the luxurious milieu he depicted.

The inclusion of these objects speaks to Croegaert's awareness of contemporary trends and his desire to create scenes that felt both opulent and current. While not a central driving force in his art as it was for some avant-garde painters, the presence of Japanese elements underscores the interconnectedness of global cultures and their impact on European art and design during this period.

Artistic Circle and Contemporaries

While Georges Croegaert pursued his own distinct path, he operated within the bustling Parisian art world and can be situated relative to various contemporaries. His primary connections seem to be with other artists working in similar veins, particularly those specializing in genre scenes and the popular Cardinal Paintings. His relationship with the work of Jehan Georges Vibert is undeniable, as both catered to the same market with similar themes, though each maintained his own stylistic nuances. Andrea Landini was another key figure in this specific subgenre.

As a Belgian artist successful in Paris, he can be compared to Alfred Stevens, who also achieved fame depicting elegant women and fashionable interiors, albeit often with a slightly more modern, painterly touch. Croegaert's meticulous academic style places him closer to the established masters of the French Salon, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, or Alexandre Cabanel, who upheld the values of traditional craftsmanship and idealized or narrative subjects, though Croegaert's subject matter often had a more contemporary or humorous edge.

His work stands in contrast to the revolutionary movements unfolding simultaneously. The Impressionists (Monet, Renoir, Degas) were challenging academic conventions with their focus on light, color, and modern life rendered with spontaneous brushwork. Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh were exploring expressive color and form. Symbolists, including fellow Belgian Fernand Khnopff, were delving into dreamlike and mystical themes. Croegaert remained largely apart from these avant-garde developments, instead perfecting his craft within a more conservative, but highly popular and commercially viable, tradition. His inclusion of cats in some paintings adds a charming, anecdotal touch, perhaps reflecting the growing place of pets in bourgeois households or simply adding another element of domesticity and gentle humor.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Georges Croegaert enjoyed a long and successful career, sustained by a consistent demand for his work, particularly from British and American collectors who appreciated his technical skill and engaging subject matter. He continued to paint and exhibit, maintaining his studio in Paris and living comfortably from the proceeds of his art. He resided for many years in an elegant part of the city, reflecting the success he had achieved. He passed away in 1923.

In assessing Georges Croegaert's historical position, he is recognized as a highly accomplished academic painter, a master technician with an exceptional ability to render textures and details. He excelled in capturing the elegance and material culture of the Belle Époque upper classes. His Cardinal Paintings represent a significant contribution to a specific and popular genre of the time, offering humorous social commentary wrapped in exquisite craftsmanship. His works serve as valuable documents of the tastes and preoccupations of his era.

While not considered an innovator who radically altered the course of art history in the manner of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, Croegaert holds a secure place as a leading exponent of his chosen genres. His paintings remain popular with collectors today, admired for their beauty, skill, and witty observation. He represents the enduring appeal of well-crafted, narrative painting that catered to the sophisticated tastes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century art market.

Conclusion: A Master of Detail and Wit

Georges Croegaert's artistic journey took him from the traditional academies of Antwerp to the heart of the Parisian art world, where he forged a successful career through technical brilliance and astute choices of subject matter. As a chronicler of feminine elegance and a gentle satirist of clerical life, he created a body of work that delighted contemporary audiences and continues to engage viewers today. His mastery of detail, particularly in rendering luxurious fabrics and interiors, remains impressive. His Cardinal Paintings offer a unique blend of humor and social observation, capturing a specific cultural moment with charm and skill. Though operating outside the main currents of modernist innovation, Georges Croegaert stands as a significant and highly skilled painter whose work provides a rich and rewarding glimpse into the visual culture of the Belle Époque.