Julius LeBlanc Stewart, often affectionately nicknamed "the Parisian from Philadelphia," stands as a fascinating figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art. An American by birth but a Parisian by choice and artistic spirit, Stewart masterfully captured the opulence, leisure, and social intricacies of the Belle Époque. His canvases are vibrant testimonials to an era of unprecedented wealth, cultural effervescence, and transatlantic artistic exchange, positioning him as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, chronicler of his time.

Born on September 6, 1855, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Julius Stewart was destined for a life immersed in art and high society. His father, William Hood Stewart, was a prominent sugar millionaire whose immense wealth not only provided a comfortable upbringing but also facilitated deep connections within the art world. The elder Stewart was a notable art collector and patron, particularly of contemporary Spanish and French artists, which undoubtedly exposed young Julius to art from an early age.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

In 1865, when Julius was just ten years old, the Stewart family relocated to Paris. This move was pivotal, placing the young, impressionable boy at the very heart of the Western art world during a period of dynamic change and artistic innovation. Paris was the undisputed capital of art, attracting aspiring talents from across the globe, and the Stewart family’s wealth and social standing provided Julius with unparalleled access to this vibrant milieu.

His formal artistic education began under the tutelage of artists patronized by his father. Initially, he studied with the Spanish painter Eduardo Zamacois y Zabala, known for his detailed genre scenes and historical subjects. Zamacois, a friend of Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, was part of a circle of Spanish artists in Paris who enjoyed considerable success. This early exposure to the Spanish school, with its rich colors and often meticulous detail, would leave a subtle imprint on Stewart's developing style.

Stewart's most significant academic training, however, came at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French academic art. There, he became a pupil of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most influential academic painters of the 19th century. Gérôme was renowned for his historical paintings, Orientalist scenes, and mythological subjects, all executed with polished precision and a commitment to anatomical accuracy. Studying under Gérôme instilled in Stewart a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the traditional techniques of oil painting. Gérôme's studio was a melting pot of international students, including notable figures like Thomas Eakins and Frederick Arthur Bridgman, further broadening Stewart's artistic horizons.

He also received guidance from Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta, another celebrated Spanish painter based in Paris, son of the famed portraitist Federico de Madrazo and brother-in-law to Mariano Fortuny. Madrazo was particularly known for his society portraits and genre scenes, characterized by an elegant, fluid brushwork and a keen eye for capturing the fashionable attire and sophisticated ambiance of his sitters. Madrazo's influence is perhaps most evident in Stewart's own society portraits and depictions of leisurely upper-class life.

The Parisian Art World and Stewart's Emergence

The Paris in which Stewart matured as an artist was a city undergoing profound transformation. The Second Empire had given way to the Third Republic, and Baron Haussmann's renovations had reshaped the city into the grand metropolis of wide boulevards and elegant parks we know today. This was the era of the Impressionists – Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, and Camille Pissarro – who were challenging the academic establishment with their revolutionary approaches to light, color, and subject matter.

While Stewart's training was firmly rooted in the academic tradition, he was not immune to the artistic currents swirling around him. He began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in 1878, the official, juried art exhibition that was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success. The Salon, despite the growing influence of independent exhibitions, remained a powerful institution. Stewart's ability to consistently have his works accepted and favorably reviewed at the Salon speaks to his technical skill and his alignment with prevailing, albeit evolving, tastes.

His early works often depicted historical or literary themes, reflecting his academic training. However, he soon found his true calling in portraying the contemporary life of the wealthy, cosmopolitan elite among whom he moved. His family's social connections provided him with an entrée into this exclusive world, and his charming personality and artistic talent made him a welcome presence.

Stewart's Signature Style: Elegance and Observation

Julius LeBlanc Stewart developed a style that, while grounded in academic realism, possessed a vivacity and contemporary sensibility that appealed to his audience. His paintings are characterized by their luminous color palettes, sophisticated compositions, and meticulous attention to the details of fashion, interiors, and social etiquette. He had a particular talent for capturing the textures of luxurious fabrics – silks, satins, velvets – and the play of light on surfaces.

Unlike some of his academic contemporaries, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Alexandre Cabanel, whose work often focused on mythological or allegorical subjects rendered with an almost photographic smoothness, Stewart's brushwork could be more varied. While maintaining a high degree of finish, especially in portraits, there are passages in his larger genre scenes that show a slightly looser, more painterly touch, perhaps a subtle nod to the Impressionistic atmosphere of the time.

His compositions are often complex, featuring multiple figures engaged in social activities – conversations at soirées, leisurely moments on yachts, or gatherings for afternoon tea. He skillfully arranged these groups to create a sense of naturalism and narrative interest, drawing the viewer into the scene. There's an almost theatrical quality to some of his works, as if capturing a moment in an unfolding drawing-room drama.

Key Themes and Subjects in Stewart's Oeuvre

Stewart's body of work largely revolves around the depiction of the affluent Franco-American and international society in Paris and its fashionable resorts. He became a visual historian of their pastimes, their rituals, and their environment.

Portraits of the Elite

Portraiture was a significant aspect of Stewart's career. He painted numerous members of prominent American and European families, including the Vanderbilts, the Rothschilds, and various titled aristocrats. These portraits were not merely likenesses but also statements of social status, often depicting sitters in opulent settings, adorned in the latest fashions. His ability to flatter his subjects while retaining a sense of their personality contributed to his success. In this, he shared a common ground with other successful society portraitists of the era, such as John Singer Sargent, Giovanni Boldini, and Paul César Helleu, though each had their distinct stylistic approach. Sargent, for instance, often brought a dazzling bravura and psychological insight, while Boldini was known for his dynamic, almost flamboyant, portrayals.

The Social Whirl: Balls, Teas, and Leisure

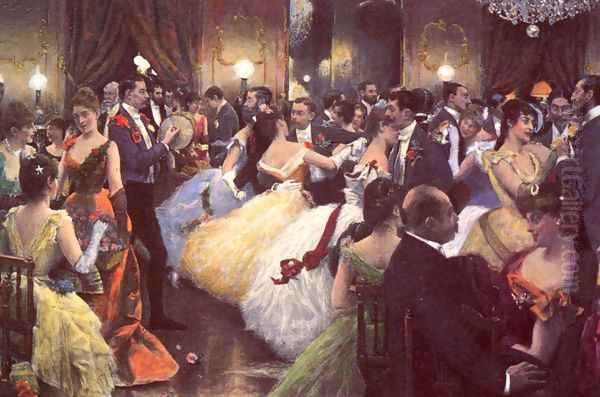

Stewart is perhaps best known for his large-scale genre paintings depicting the social life of the Belle Époque. Works like The Hunt Ball (1885) and After the Wedding (1880) are masterful orchestrations of numerous figures, capturing the energy and elegance of these grand occasions. These paintings are rich in anecdotal detail, offering glimpses into the interactions and unspoken narratives within these gatherings.

Five O'Clock Tea (1884), also known as The Five O'Clock Tea or Afternoon Tea, is another iconic work. It portrays a group of elegantly dressed women in a sumptuously decorated interior, engaged in the fashionable ritual of afternoon tea. The painting is a study in social dynamics, refined manners, and the display of wealth and taste. The careful rendering of the tea service, the floral arrangements, and the fashionable gowns showcases Stewart's keen eye for detail and his ability to evoke an atmosphere of sophisticated leisure. Such scenes of domestic or social ritual were also popular with artists like James Tissot, who similarly chronicled the lives of the fashionable, and Mary Cassatt, who offered a more intimate, often female-centered perspective on similar social strata.

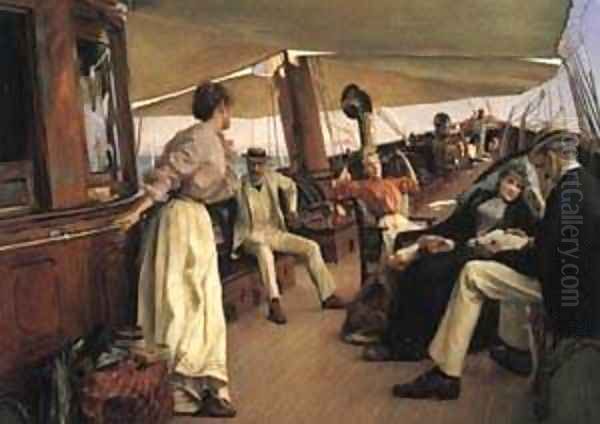

Yachting and Outdoor Scenes

Reflecting the leisure pursuits of his wealthy patrons and friends, Stewart also painted numerous scenes of yachting and seaside life. His father was an avid yachtsman, and Julius often joined him on cruises. These experiences provided rich material for his art. Yachting on the Mediterranean (1896) is a prime example, depicting a lively group enjoying a sunny day at sea. The painting captures the brilliance of the Mediterranean light, the movement of the waves, and the relaxed elegance of the figures. These works demonstrate Stewart's ability to handle complex outdoor scenes, with a particular skill in rendering the effects of sunlight on water and fabric. His interest in modern leisure aligns him with Impressionists like Monet and Renoir, who also depicted Parisians enjoying their newfound free time in suburban and coastal settings, though Stewart's approach remained more polished and narrative.

Nudes and Later Religious Works

While best known for his society scenes, Stewart also explored other genres. He painted a number of nudes, often set in outdoor, idyllic landscapes, such as Nude in the Forest. These works, while adhering to academic conventions of form and anatomy, sometimes possess a sensuality and naturalism that distinguishes them. The tradition of the female nude was, of course, central to academic art, with artists like Gérôme and Cabanel producing famous examples, but Stewart's nudes often feel less mythological and more directly observed.

In his later years, Stewart turned increasingly to religious subjects. The Baptism (1892) is a significant work from this period. It was exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where it received acclaim, and later at the Berlin International Exposition in 1895. This shift in subject matter might reflect a personal spiritual evolution or a desire to engage with more profound themes as the ebullience of the Belle Époque began to wane with the approaching shadows of World War I. This thematic turn was not uncommon; even artists known for secular subjects sometimes explored religious iconography later in their careers.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Stewart's paintings stand out for their artistic merit and their encapsulation of his era.

After the Wedding (1880): This early success depicts the moments after a wedding ceremony, with guests mingling and the bride and groom at the center. It showcases Stewart's ability to manage a large, multi-figure composition and to capture the varied emotions and interactions of such an event. The attention to the details of the wedding attire and the opulent setting are characteristic.

Five O'Clock Tea (1884): As mentioned, this work is a quintessential depiction of Belle Époque social ritual. The soft lighting, the rich textures of the dresses and furnishings, and the subtle interplay between the figures create a captivating scene of refined domesticity and social grace. It invites comparison with similar scenes by contemporaries like Jean Béraud, who specialized in capturing Parisian daily life, though Béraud often focused on more public, outdoor scenes.

The Hunt Ball (1885): Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1885, this ambitious canvas captures the glamour and energy of a high-society ball. The swirling gowns, the animated conversations, and the overall sense of movement and excitement are rendered with great skill. It’s a testament to Stewart's mastery of large-scale genre painting.

The Baptism (1892): This large painting depicts a christening ceremony, likely within a wealthy family. The composition is formal yet imbued with a sense of solemnity and intimacy. The figures are rendered with sensitivity, and the play of light, perhaps from a nearby window, illuminates the scene. Its positive reception at international exhibitions underscores its quality.

Yachting on the Mediterranean (1896): This vibrant work is one of Stewart's most celebrated outdoor scenes. The brilliant sunlight, the deep blue of the sea, and the relaxed, elegant figures aboard the yacht convey a sense of idyllic leisure. The painting achieved a record auction price for the artist in 2005, selling for ,312,000, highlighting its enduring appeal and market recognition. The depiction of modern leisure on the water also finds parallels in the work of Impressionists like Gustave Caillebotte, who painted boating scenes on the Seine.

Contemporaries, Connections, and Influence

Julius LeBlanc Stewart operated within a rich network of artists. His teachers – Zamacois, Gérôme, and Madrazo – provided him with a strong technical grounding. His father's patronage connected him to artists like Mariano Fortuny, whose brilliant technique and Orientalist subjects were highly influential in the 1860s and 70s.

He was a contemporary of other American expatriate artists in Paris, most notably John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler. While Whistler pursued a more aesthetic and tonal approach, Sargent, like Stewart, excelled in society portraiture and capturing the elegance of their shared milieu. However, Sargent's brushwork was generally bolder and his psychological penetration often deeper. Stewart's style was perhaps closer to that of other society painters like the Italian Giovanni Boldini, known for his flamboyant and dynamic portraits, or the Frenchman Paul César Helleu, celebrated for his graceful drypoint etchings and paintings of fashionable women.

Stewart was also friendly with prominent figures outside the art world, such as James Gordon Bennett Jr., the publisher of the New York Herald, whose yacht, the "Namouna," was the subject of one of Stewart's paintings. These connections were vital for commissions and for maintaining his presence within the elite circles he depicted.

His influence on subsequent artists is perhaps less direct than that of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists. However, his work provides an invaluable visual record of the Belle Époque, and his success demonstrated that an American artist could thrive in the competitive Parisian art world by catering to the tastes of the international elite. He, along with artists like Sargent and Alexander Harrison (known for his marine paintings), helped to raise the profile of American art on the international stage.

The "Parisian from Philadelphia": A Unique Position

Stewart's nickname, "le Parisien de Philadelphie," aptly summarizes his dual identity. He was an American who fully assimilated into Parisian life and culture, yet his American roots and connections remained important. He often depicted fellow Americans in Paris, and his work was exhibited in both France and the United States.

His financial independence, thanks to his family's wealth, allowed him a degree of freedom in his artistic pursuits. He was not solely reliant on commissions for survival, which perhaps enabled him to undertake large, ambitious genre scenes that might have been commercially riskier for other artists. This privileged position also gave him insider access to the world he painted, lending an authenticity to his depictions.

His art reflects the cosmopolitanism of the era, a time when wealthy Americans flocked to Europe, particularly Paris, for culture, education, and social advancement. Stewart's paintings are a window into this transatlantic world, where American heiresses married into European aristocracy and Paris was the ultimate arbiter of taste and fashion.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Appeal

Julius LeBlanc Stewart continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century. He remained in Paris for most of his life, witnessing the dramatic societal shifts brought about by industrialization, new technologies, and eventually, the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The war effectively brought an end to the Belle Époque, the glittering world he had so assiduously chronicled.

He passed away in Paris on January 4, 1919, shortly after the war's end. By this time, the art world had been irrevocably changed by modernism. Cubism, Fauvism, and other avant-garde movements had long since supplanted academic art and even Impressionism as the cutting edge of artistic innovation. Artists like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Georges Braque were now leading the charge.

For a period, Stewart, like many academic and society painters of his generation, fell into relative obscurity as tastes shifted. However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for the art of the Belle Époque and for artists who captured its unique character. Stewart's paintings are now sought after by collectors and are found in the collections of museums such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

His enduring appeal lies in his technical skill, the charm and elegance of his subjects, and the fascinating glimpse he offers into a bygone era. His works are more than just pretty pictures; they are historical documents, rich with information about the customs, fashions, and social dynamics of late 19th-century high society. They transport viewers to a world of opulence and refinement, a world that, for all its superficiality, held a powerful allure.

Conclusion: Chronicler of a Gilded Age

Julius LeBlanc Stewart was a product of his time and his privileged circumstances. He used his talent and his unique access to create a body of work that celebrates the beauty, leisure, and social intricacies of the Belle Époque. While he may not have been an artistic revolutionary in the mold of the Impressionists or later modernists, his contribution as a skilled observer and masterful renderer of his world is undeniable.

As an American artist who achieved significant success in Paris, he played a role in the internationalization of art. His paintings, with their blend of academic polish and contemporary sensibility, found favor with a wealthy, cosmopolitan clientele. Today, his works continue to captivate audiences, offering a luminous window onto the "beautiful era" and securing his place as a distinguished "Parisian from Philadelphia" in the annals of art history. His art serves as a vibrant reminder of a time when Paris was the undisputed center of the world, and American artists like Stewart flocked there to learn, to create, and to capture its dazzling spectacle.