Georges de La Tour stands as one of the most distinctive and compelling figures of French Baroque painting. Celebrated for his profound understanding of light and shadow, particularly his mesmerizing candlelit scenes, La Tour crafted a body of work that is both deeply spiritual and strikingly human. After centuries of relative obscurity, his rediscovery in the early 20th century revealed an artist of singular vision, whose paintings continue to captivate audiences with their quiet intensity and masterful execution. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of a painter who, from the Duchy of Lorraine, cast a unique light on the 17th-century European art scene.

Early Life and Lorraine's Cultural Crucible

Georges de La Tour was born on March 14, 1593, in the small town of Vic-sur-Seille, then a significant administrative and religious center in the Bishopric of Metz, within the Duchy of Lorraine. Lorraine, at this time, was an independent duchy, a cultural crossroads between France, the Germanic lands, and the Netherlands, fostering a rich artistic environment. His father, Jean de La Tour, was a baker, and his mother, Sibylle Mélian (sometimes recorded as Sybille de Crospaux or Molian), is believed to have come from a family of minor nobility. This mixed heritage might have provided young Georges with certain social advantages or aspirations.

The details of La Tour's early training remain one of the great mysteries of art history. No definitive records document his apprenticeship. However, Vic-sur-Seille was not an artistic backwater; it was home to artists and craftsmen, and the influence of nearby artistic centers like Nancy, the ducal capital, would have been felt. It is plausible he received initial training locally. The broader artistic currents of the time, particularly the dramatic realism and tenebrism of Caravaggio, were sweeping across Europe, and Lorraine was not immune to these influences. Artists like Jacques Bellange, a prominent Mannerist active in Nancy, represented an older tradition, but new ideas were certainly percolating.

Marriage, Lunéville, and a Burgeoning Career

In 1617, Georges de La Tour married Diane Le Nerf, who hailed from a noble family in Lunéville, another important town in Lorraine. This marriage was a significant step, likely elevating his social standing. The couple settled in Lunéville by 1620, and it was here that La Tour established himself as a successful painter. Records indicate he became a respected citizen, though perhaps a somewhat contentious one, known for his assertive, even aggressive, personality in business dealings and disputes with fellow townsfolk.

Lunéville provided a stable base for La Tour's artistic production. He ran a workshop, and his reputation grew, attracting commissions from local nobility, the bourgeoisie, and religious institutions. He fathered several children, including a son, Étienne, born in 1621, who would also become a painter and likely assisted in his father's studio, eventually inheriting it. Despite his provincial base, La Tour's fame seems to have reached beyond Lorraine. There is evidence suggesting he received patronage from King Louis XIII of France, who is said to have acquired his Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene and even granted him the title of "Peintre ordinaire du Roi" (Painter to the King) around 1638 or 1639. This royal recognition, however, did not necessarily translate into a move to Paris or a central role in the French court's artistic life, which was then dominated by figures like Simon Vouet.

The Unresolved Question of Artistic Formation: Italy or the Netherlands?

The precise sources of La Tour's distinctive style, particularly his mastery of chiaroscuro, remain a subject of scholarly debate. Did he travel to Italy to experience Caravaggio's work firsthand? Or did he encounter Caravaggism through the Utrecht Caravaggisti in the Netherlands, such as Gerrit van Honthorst, Hendrick ter Brugghen, or Dirck van Baburen, who had absorbed the Italian master's style and brought it north?

There is no documentary proof of La Tour undertaking such journeys. However, the stylistic affinities are undeniable. His dramatic use of a single light source, often a candle, to illuminate figures emerging from deep shadow, echoes Caravaggio's tenebrism. The earthy realism of his figures, whether saints or peasants, also aligns with the Caravaggesque approach. If he did not travel, he could have seen works by Caravaggio or his followers that had made their way to Lorraine or nearby regions, or he might have been influenced by prints.

The connection to the Utrecht Caravaggisti is particularly compelling. Gerrit van Honthorst, known as "Gherardo delle Notti" (Gerard of the Night Scenes) for his candlelit compositions, achieved international fame. La Tour's nocturnal scenes share a similar sensibility, though La Tour often achieves a greater sense of stillness, introspection, and geometric simplification than his Dutch counterparts. Hendrick ter Brugghen, another leading Utrecht Caravaggist, also explored religious and genre scenes with a powerful, often melancholic, realism that resonates with La Tour's art. Indeed, for a long time, some of La Tour's works were misattributed to artists like Ter Brugghen.

The Signature Style: Master of Light and Shadow

Georges de La Tour's most defining characteristic is his extraordinary use of light. He is often dubbed the "painter of light," specifically the intimate, focused light of a candle, a torch, or a hidden source that sculpts forms out of darkness. This is not merely a technical device but a means of creating profound psychological and spiritual atmospheres. His figures, often simplified into almost geometric volumes, possess a monumental quality, regardless of their social standing.

His palette is typically restrained, favoring rich reds, browns, and ochres, which glow warmly in the candlelight. The surfaces of his paintings are smooth, with little visible brushwork, contributing to the sense of stillness and timelessness. This meticulous finish and the simplification of forms lend his work an almost abstract quality, setting him apart from many of his more flamboyant Baroque contemporaries like Peter Paul Rubens or even the more classical French painters like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, who explored light in grander, often landscape-oriented, compositions.

La Tour's oeuvre can be broadly divided into two categories: his "night scenes" (nocturnes) and his "daylight scenes." The nocturnes, illuminated by a single, often visible, candle, are perhaps his most famous and innovative works. The daylight scenes, though fewer in number, are equally powerful, characterized by a cool, clear light and a sharp focus on character and narrative.

Sacred Narratives: The Candlelit Path to Devotion

Religion was a dominant force in 17th-century Europe, and Lorraine, staunchly Catholic, was deeply affected by the Counter-Reformation. La Tour produced numerous religious paintings, many of which are imbued with a quiet, intense piety that reflects this spiritual climate. His religious nocturnes are particularly remarkable for their ability to transform biblical stories into intimate, human dramas.

The Penitent Magdalene exists in several versions (e.g., Wrightsman version, Frick Collection; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Louvre Museum, Paris), each depicting Mary Magdalene in contemplation, typically with a skull, a mirror, and a candle. The flame of the candle is often the central focus, its light catching the Magdalene's face, her reflective mood, and the symbolic objects around her. These paintings are not just depictions of a saint but profound meditations on sin, repentance, and spiritual illumination. The stillness and simplified forms create an atmosphere of profound introspection.

Saint Joseph the Carpenter (Louvre Museum, Paris) is another iconic work. It shows a young Jesus holding a candle, its light illuminating the face of his elderly father, Joseph, who is at work drilling a piece of wood. The wood, shaped like a cross, and the auger, prefigure Christ's Passion. The light from the candle held by the divine child is almost translucent, casting a spiritual glow on the scene. The tenderness between father and son, combined with the somber foreshadowing, makes this a deeply moving image.

Other significant religious nocturnes include The Adoration of the Shepherds (Louvre Museum, Paris), where the Christ child himself seems to be the source of a gentle, divine light, and The Newborn Christ (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes), a work of breathtaking tenderness and simplicity, where Saint Anne shields the candle flame as she and Mary gaze upon the infant Jesus. The scene is hushed, reverent, and intensely personal. Christ with Saint Joseph in the Carpenter's Shop (another version, location varies) also explores this theme with profound sensitivity.

Genre Scenes and Moral Allegories: Daylight Realism

While best known for his candlelit religious scenes, La Tour also painted striking daylight genre scenes, often depicting peasants, musicians, and card players. These works showcase his keen observation of human character and his ability to imbue everyday subjects with a sense of gravity.

The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds (Louvre Museum, Paris) and its variant, The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs (Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth), are among his most celebrated daylight paintings. They depict a young, naive nobleman being fleeced at cards by a courtesan and two accomplices. The psychological tension, the subtle glances, and the rich costumes are rendered with brilliant clarity. These paintings serve as moral allegories, warning against the vices of gambling and deceit, a common theme in 17th-century art, also explored by Caravaggio in works like The Cardsharps.

The Fortune Teller (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is another captivating genre scene. A young man is having his fortune told by an old Romani woman, while her companions slyly pick his pockets. The painting is a masterclass in narrative detail and psychological interplay, rendered in La Tour's characteristic clear light and smooth finish. The authenticity of this work was once debated but is now widely accepted, showcasing his skill in complex multi-figure compositions.

Paintings of musicians, such as The Hurdy-Gurdy Player (Musée d'Arts de Nantes), often depict solitary, sometimes blind, figures, rendered with a stark realism that evokes both pathos and dignity. These works, like his religious paintings, often strip away extraneous detail to focus on the essential humanity of the subject. The Le Nain brothers (Antoine, Louis, and Mathieu), also active in France during this period, similarly depicted peasant scenes with a sense of dignity, though their style and approach to light differed significantly from La Tour's.

Notable Masterpieces: A Closer Look

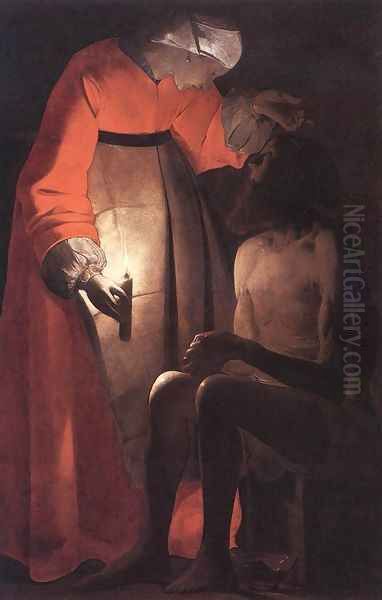

Beyond those already mentioned, several other works underscore La Tour's genius. Job Mocked by his Wife (Musée Départemental d'Art Ancien et Contemporain, Épinal) is a powerful nocturne depicting the suffering Old Testament figure. The single candle illuminates Job's emaciated form and the scornful face of his wife, creating a scene of intense drama and pathos.

Saint Jerome Reading (versions in the Louvre and elsewhere) shows the scholar saint absorbed in his texts, often by candlelight, emphasizing the theme of spiritual learning and contemplation. These images resonate with the intellectual currents of the Counter-Reformation, which valued scholarship and theological study.

The various depictions of Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene (versions in the Louvre, Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Kimbell Art Museum) are among La Tour's most poignant. The near-lifesize figures, the dramatic use of light (often a torch), and the tender care shown by Irene for the wounded saint create a powerful emotional impact. It was a version of this subject that reportedly captivated Louis XIII.

Contemporaries and the Wider Artistic Milieu

La Tour worked somewhat in isolation in Lorraine, yet he was part of a broader European artistic context. In Paris, Simon Vouet, who had spent years in Italy, returned in 1627 to become a dominant figure, popularizing a lighter, more decorative Baroque style. Philippe de Champaigne, another prominent Parisian painter of Flemish origin, was known for his austere portraits and religious works, influenced by Jansenism, offering a different kind of spiritual intensity. Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, though French, spent most of their careers in Rome, developing a classical style that would become highly influential in French academic art. Charles Le Brun would later rise to prominence under Louis XIV, defining the grand style of the French Academy.

La Tour's Caravaggism, therefore, was somewhat distinct from the prevailing trends in Paris. His closest artistic relatives, stylistically, were the Utrecht Caravaggisti. However, La Tour's art possesses a unique stillness and psychological depth that sets it apart. While Caravaggio's figures often display raw, overt emotion, and Honthorst's can be boisterous, La Tour's subjects are typically absorbed in quiet contemplation or subtle interaction. Even in a dramatic scene like The Cheat, the action unfolds with a kind of hushed intensity.

It's also worth noting that while La Tour's work was admired, his direct influence on subsequent generations of French painters seems to have been limited, partly due to his provincial location and his eventual slide into obscurity. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, working in the 18th century, would later explore themes of everyday life and the quiet dignity of simple objects with a sensitivity that, in retrospect, shares some spiritual affinity with La Tour, though their styles are distinct. The Rococo exuberance of Antoine Watteau or Jean-Honoré Fragonard represents a very different sensibility from La Tour's solemnity.

The "Lost" Master: Oblivion and Rediscovery

Despite his contemporary success and even royal patronage, Georges de La Tour was largely forgotten after his death. His name faded from art historical accounts, and his works were often misattributed to other artists, including Spanish painters like Francisco de Zurbarán or Francisco Ribalta, or Dutch artists like Vermeer (due to the quiet intimacy) or the Utrecht Caravaggisti. The turmoil of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which devastated Lorraine, may have contributed to the dispersal or loss of records and artworks.

The remarkable rediscovery of Georges de La Tour began in the early 20th century. The German art historian Hermann Voss is credited with a pivotal role. In an article published in 1915, "Georges du Mesnil de La Tour," Voss identified a core group of paintings as the work of this forgotten Lorraine master, linking them to archival mentions. This sparked a wave of scholarly interest and a gradual reattribution of works. Exhibitions, such as the landmark "Peintres de la Réalité en France au XVIIe Siècle" (Painters of Reality in 17th Century France) held in Paris in 1934, were crucial in reintroducing La Tour to the public and cementing his reputation.

Since then, ongoing research has expanded his known oeuvre, though it remains relatively small (around 40-50 accepted works, with ongoing debates about some attributions). The discovery of new documents and the technical analysis of paintings continue to shed light on his career and techniques.

Unresolved Mysteries and Scholarly Debates

Several aspects of La Tour's life and work remain enigmatic. The lack of detailed knowledge about his training is a significant gap. The precise nature of his relationship with the French court and the extent of his fame outside Lorraine are still being explored.

The attribution of certain works continues to be debated. For instance, the group of paintings known as the "Dice Players" or "Payment of Dues" has a different, rougher handling than many of his polished nocturnes, leading to questions about their authorship or their place within his development. The exact chronology of his works is also challenging to establish definitively, as few are dated. Scholars often rely on stylistic evolution, moving from more detailed, daylight scenes to the increasingly simplified and spiritual nocturnes.

His studio practices are another area of interest. How large was his workshop? What was the role of his son Étienne? Did Étienne paint works in his father's style that are now attributed to Georges? These questions are common in the study of Old Masters but are particularly pertinent for an artist whose oeuvre was reconstructed relatively recently.

Later Life, Death, and Enduring Legacy

The later years of La Tour's life in Lunéville were marked by the ongoing conflicts and hardships of the Thirty Years' War. Lorraine suffered greatly during this period, with famine, plague, and military occupation. Despite these challenges, La Tour seems to have maintained his artistic production and his status in the community.

Georges de La Tour died in Lunéville on January 30, 1652, reportedly a victim of an epidemic (possibly plague) that also claimed the lives of his wife, Diane, and a servant just weeks earlier. His son, Étienne, inherited his father's studio and continued to work as a painter, though his own artistic identity is not well defined, and he seems to have largely worked in his father's manner.

For nearly three centuries, La Tour remained a footnote in art history. His rediscovery, however, has established him as one of the great masters of the 17th century. His work resonates with modern sensibilities due to its psychological depth, its formal simplification, and its masterful control of light. He is seen not just as a follower of Caravaggio but as an artist who absorbed those influences and forged a deeply personal and original style. His paintings invite quiet contemplation, drawing the viewer into a world of hushed reverence and profound human emotion. The "Master of Lunéville" may have been lost to time for a while, but his luminous art now shines brightly, a testament to his unique genius.

Conclusion: The Quiet Power of a Singular Vision

Georges de La Tour's journey from provincial success to centuries of obscurity and finally to celebrated rediscovery is a fascinating chapter in art history. His ability to infuse simple scenes, whether religious or secular, with a profound sense of stillness and spiritual intensity is unparalleled. The candle flame in his paintings is more than just a source of illumination; it is a metaphor for faith, introspection, and the fragile beauty of human existence. In a Baroque era often characterized by dynamism and opulence, La Tour offered a contrasting vision of quiet power, geometric order, and deep psychological insight. His legacy is a collection of hauntingly beautiful images that continue to speak to the enduring human search for meaning and transcendence, rendered by a true master of light and shadow.