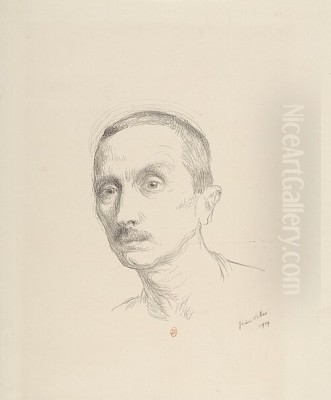

Jean Veber, a prominent figure in French art at the turn of the 20th century, carved a unique niche for himself as a painter, printmaker, and, most notably, a caricaturist of formidable power. Born in Paris in 1864, not 1868 as sometimes mistakenly cited, and passing away in 1928, Veber's life and career spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic upheaval in France. His work, characterized by its biting satire and unflinching gaze upon the hypocrisies of his time, continues to resonate for its artistic merit and its sharp socio-political commentary. He was an artist who wielded his brush and etching needle with the precision of a surgeon and the wit of a provocateur, leaving behind a legacy that is both controversial and compelling.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jean Veber's artistic journey began in the heart of Paris, the epicenter of European art. He received his formal training at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, an institution that, while steeped in academic tradition, produced artists who would go on to challenge and redefine art. During his formative years, the Parisian art scene was a vibrant tapestry woven with threads of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement. While Veber would develop a style distinctly his own, the environment undoubtedly exposed him to a rich array of artistic philosophies and techniques.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who might have focused on landscape, portraiture in the traditional sense, or mythological scenes, Veber was drawn to the human condition, particularly its absurdities and injustices. His training at the Beaux-Arts would have equipped him with strong foundational skills in drawing and composition, skills he would later deploy with devastating effect in his satirical works. The academic rigor of the Beaux-Arts, often associated with artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Alexandre Cabanel, provided a technical base from which Veber could launch his more subversive artistic explorations.

The Emergence of a Satirical Voice

Veber quickly found an outlet for his critical eye in the burgeoning illustrated press of Paris. He became a notable illustrator for journals such as Gil Blas, a popular literary and political daily. His contributions to satirical magazines like L'Assiette au Beurre and Le Rire cemented his reputation as a fearless commentator. These publications were known for their audacious content, often pushing the boundaries of censorship and societal decorum. In this milieu, Veber thrived, alongside other talented illustrators and caricaturists who defined the era's graphic satire.

His work for these journals was not mere entertainment; it was a form of social and political activism. Veber targeted a wide range of subjects: the arrogance of political figures, the moral failings of the bourgeoisie, the perceived hypocrisy of religious institutions, and the often-brutal realities of colonialism and militarism. His style was incisive, often grotesque, and always thought-provoking. He did not shy away from depicting the uncomfortable, using exaggeration and symbolism to lay bare the underlying truths he perceived in society. This commitment to social critique places him in a lineage of great French satirists, harking back to Honoré Daumier, whose own work had powerfully critiqued 19th-century French society.

Mastery Across Mediums: Painting, Printmaking, and Illustration

While best known for his caricatures and illustrations, Jean Veber was a versatile artist proficient in several mediums. His paintings, though perhaps less widely recognized today than his graphic work, demonstrate his skill in composition and color. However, it was in printmaking, particularly lithography, that Veber truly excelled. Lithography, with its capacity for rich tonal variations and directness of mark-making, proved an ideal medium for his expressive and often dark visions. He explored its potential with considerable skill, producing prints that were both technically accomplished and thematically potent.

His illustrations extended beyond periodical contributions. A significant project was his series of illustrations for Jules Massenet's opera Thaïs. For this, Veber employed a five-color copperplate printing technique, showcasing his technical ingenuity and his ability to interpret literary and musical themes visually. These illustrations, likely imbued with his characteristic flair for drama and psychological depth, would have offered a unique visual counterpart to Massenet's famous opera. His ability to adapt his style to different narrative forms, from opera to children's books like Les Enfants s'amusent, highlights his versatility.

Iconic Works and Their Resonant Themes

Several of Jean Veber's works stand out for their artistic power and the controversies they ignited. His art often delved into themes of power, corruption, sexuality, and the darker aspects of human nature, making him a precursor to some of the more unsettling explorations of 20th-century art.

One of his notable creations is Les Sorcières (The Witches), a color copperplate print from 1900. This piece, likely tapping into the fin-de-siècle fascination with the occult, the erotic, and the grotesque, would have showcased Veber's imaginative power and his skill in creating complex, allegorical scenes. Such imagery resonated with the Symbolist undercurrents of the era, seen in the works of artists like Odilon Redon, though Veber’s approach was often more direct and satirical than purely ethereal or dreamlike.

A particularly impactful and controversial work was Les Camps de Reconnaissance au Transvaal. This piece directly addressed the atrocities of the Second Boer War, specifically the British use of concentration camps. Veber's unflinching depiction of suffering was a powerful indictment of imperial brutality and brought international attention to the horrors of the conflict. It demonstrated his willingness to use art as a weapon against injustice, a characteristic shared by artists like Francisco Goya in his Disasters of War series, though from a different historical context.

His illustration Ulysses et Nausicaä, depicting a scene from Homer's Odyssey, shows another facet of his work – an engagement with classical literature. However, even in such traditional subjects, Veber likely brought his unique perspective, perhaps infusing the scene with psychological tension or subtle social commentary, influenced by contemporaries like Théophile Steinlen or Charles Léandre, who were also known for their illustrative work.

Controversy and Public Outcry

Jean Veber's art was not designed to soothe or placate; it was intended to provoke, and provoke it did. Several of his works caused significant public and official outcry, cementing his reputation as an enfant terrible of the Parisian art scene.

In 1897, he created a caricature depicting Otto von Bismarck, the former German Chancellor, as a monstrous butcher, his hands and apron stained with blood, surrounded by dismembered bodies. This visceral image, a potent commentary on Bismarck's "blood and iron" policy and its consequences, caused a diplomatic incident, with official protests lodged by Germany. The audacity of the portrayal and its political implications highlighted the power of caricature as a political tool.

Four years later, Veber courted controversy again with a caricature targeting British royalty and national pride. He depicted the face of King Edward VII on the posterior of a figure representing "L'Anglais" (The Englishman) or on a ship, a direct and vulgar insult that mocked British imperialism and the King himself. This piece, like the Bismarck caricature, generated considerable offense and underscored Veber's fearless approach to satirizing powerful figures and nations. His critiques of the British, particularly concerning the Boer War, were a recurring theme, often published in journals like L'Assiette au Beurre.

Beyond specific political figures, Veber's frank and often unsettling depictions of sexuality and social mores also challenged contemporary sensibilities. His willingness to explore themes of lust, decadence, and the grotesque aspects of human desire placed him at the vanguard of artists who were dismantling Victorian-era prudishness, albeit in a manner that could be shocking to many.

Wartime Experience and Continued Artistic Production

The outbreak of World War I profoundly impacted European society, and Jean Veber, like many of his generation, was directly affected. He served in the French military during the conflict. His wartime experience was harrowing; he was a victim of a poison gas attack, an insidious new weapon that caused widespread suffering and death. This injury led to his discharge from military service in 1918.

It is plausible that his wartime experiences further fueled his critical perspective on militarism and the human cost of conflict, themes already present in his earlier work. The war's unprecedented brutality and the disillusionment it engendered found expression in the art of many artists, leading to movements like Dadaism, which shared a certain anti-establishment and absurdist spirit with Veber's earlier satirical impulses.

Despite the interruption and trauma of the war, Veber continued his artistic career. He remained active in the Parisian art world, producing paintings, prints, and illustrations. His commitment to his craft and his critical vision persisted, even as the artistic landscape began to shift dramatically in the post-war era with the rise of Surrealism and other avant-garde movements.

Artistic Milieu: Collaborations and Contemporaries

Jean Veber operated within a dynamic artistic community in Paris. He was associated with the Incohérents (Incoherents), an eclectic and somewhat anarchic group of artists and writers active in the late 19th century. Founded around 1882, the Incohérents were known for their irreverent exhibitions and publications, predating and, in some ways, anticipating the anti-art gestures of Dada. Their emphasis on humor, satire, and the absurd would have aligned well with Veber's own artistic inclinations.

His name is often mentioned alongside other prominent illustrators and caricaturists of the Belle Époque and early 20th century. Artists such as Théophile Steinlen, known for his compassionate depictions of working-class life and iconic posters like "Le Chat Noir"; Jean-Louis Forain, a sharp social satirist and painter; Adolphe Willette, with his distinctive Pierrot figures and often whimsical, sometimes biting, illustrations; and Charles Léandre, another skilled caricaturist and portraitist, were his contemporaries. These artists, along with others like Caran d'Ache (Emmanuel Poiré), known for his narrative comic strips and political cartoons, and Félix Vallotton, whose stark woodcuts offered incisive social commentary, formed a vibrant ecosystem of graphic satire.

Veber's work for Les Humoristes, a weekly publication, in 1911, saw him featured alongside Steinlen, Forain, Willette, Léandre, and an artist named Neumont, indicating his established position within this circle. While direct collaborations might have varied, the shared platforms of journals and exhibitions fostered a sense of community and, undoubtedly, a degree of friendly competition and mutual influence. The visual language of poster art, championed by figures like Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, also contributed to the graphic dynamism of the period, an environment in which Veber's bold style found a receptive audience.

Legacy, Collections, and Market Presence

Jean Veber's contributions to art were recognized during his lifetime. He was awarded a silver medal at the prestigious Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900, a testament to his standing in the art world. In 1907, he received further official recognition when he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian awards.

Today, Jean Veber's works are held in various public and private collections. The Petit Palais in Paris, a museum with significant holdings of French art from this period, has honored him with a retrospective exhibition, showcasing the breadth of his oeuvre from his birth year (correctly noted as 1864) to his death in 1928. This indicates a sustained institutional interest in his work. His art is also part of the Mobilier National collections in France, which preserves historic French state furniture and decorative arts, suggesting that some of his designs or works may have had a decorative application or were acquired for their national cultural significance.

The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours is another institution with a notable collection of Veber's art, reportedly holding 19 of his paintings, 12 designs, and 3 lithographs. This provides a valuable resource for studying his diverse output. His works also occasionally appear in the art market, with pieces like Les étourdies de monsieur Toto et de mademoiselle Nini and sketchbooks containing numerous designs coming up for auction. While not commanding the astronomical prices of some of his Impressionist or Post-Impressionist contemporaries, his works are sought after by collectors of French graphic art, satire, and Belle Époque illustration.

An Enduring Critical Voice

Jean Veber passed away in 1928, leaving behind a body of work that is as challenging as it is captivating. His art serves as a vivid, often unsettling, chronicle of his era, reflecting its anxieties, its hypocrisies, and its moments of dark humor. He was more than just an illustrator; he was a social critic who used his artistic talents to dissect and comment upon the world around him with unflinching honesty.

His legacy lies in his fearless approach to satire, his technical mastery, particularly in printmaking, and his ability to create images that continue to provoke thought and discussion. In an age where political and social caricature remains a vital form of commentary, Veber's work reminds us of the enduring power of art to question authority, challenge conventions, and expose uncomfortable truths. He stands as a significant figure in the rich tradition of French satirical art, a tradition that values wit, irreverence, and a profound engagement with the human condition. His incisive eye captured the complexities of a society on the cusp of modernity, and his art remains a potent testament to his unique vision.