Hermann Scherer stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art, particularly within the vibrant currents of Swiss Expressionism. A painter and sculptor, Scherer's work is characterized by its raw emotional intensity, bold use of color, and a profound engagement with the human condition. His artistic journey, though spanning little more than a decade, left an indelible mark, particularly through his association with the influential "Rot-Blau" group and his deep connection with the leading German Expressionist, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Hermann Scherer was born on February 8, 1893, in Rümmingen, a village in Baden, Germany, close to the Swiss border. This proximity to Switzerland would prove formative, as he later became a naturalized Swiss citizen and a key player in its art scene. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him in 1907, at the tender age of fourteen, to begin a stonemason apprenticeship at the Schwab workshop in Lörrach. This practical training in carving stone provided a foundational understanding of three-dimensional form and material that would later inform his powerful sculptures.

Following his apprenticeship, Scherer moved to Basel, a city with a burgeoning artistic environment. Between 1910 and 1919, he worked as an assistant to several established sculptors. This period was crucial for honing his skills and exposing him to various artistic approaches. He collaborated with Carl Gutknecht, a sculptor known for his more traditional and monumental works. He also worked with Otto Roos, another Basel-based sculptor, and later, around 1919-1920, he assisted Carl Burckhardt, a prominent Swiss sculptor whose work was transitioning from Neoclassicism towards a more modern sensibility. These experiences provided Scherer with a solid technical grounding, but his artistic spirit yearned for a more personal and expressive language.

The Pivotal Encounter with Kirchner and the Embrace of Expressionism

The early 1920s marked a critical turning point in Scherer's artistic development. A growing dissatisfaction with the more academic or traditional sculptural styles he had been practicing led him to seek new forms of expression. He was increasingly drawn to the radical innovations of German Expressionism, a movement that prioritized subjective feeling and intense emotional experience over objective reality. Artists associated with groups like "Die Brücke" (The Bridge), such as Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Emil Nolde, were forging a new visual language with their aggressive brushwork, distorted forms, and vibrant, often non-naturalistic colors.

The most decisive influence on Scherer came from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, one of the founding members of "Die Brücke." Kirchner had moved to Davos, Switzerland, in 1917, initially for health reasons, and his presence there became a magnet for younger Swiss artists. Scherer first encountered Kirchner's work through exhibitions and was profoundly affected by its power. In 1922, Scherer visited Kirchner in Davos, an encounter that would fundamentally reshape his artistic trajectory. Kirchner, himself a master of woodcut and sculpture alongside painting, encouraged Scherer to explore these media with a new expressive freedom.

Under Kirchner's mentorship, Scherer fully embraced Expressionism. He began to create woodcuts and wooden sculptures that bore the hallmarks of the movement: simplified, angular forms, a deliberate crudeness that rejected academic polish, and a focus on conveying raw emotion. Kirchner's influence is palpable in Scherer's dynamic compositions and his direct, forceful carving technique, which often left the marks of the tools visible, emphasizing the materiality of the wood. This period saw Scherer move away from stone and dedicate himself almost entirely to wood, a medium that allowed for more immediate and gestural expression.

The "Rot-Blau" Group: A Swiss Expressionist Collective

Inspired by the collaborative spirit of German Expressionist groups and fueled by his own burgeoning artistic vision, Hermann Scherer became a key figure in the formation of "Rot-Blau" (Red-Blue) in Basel at the end of 1924 and early 1925. He co-founded the group with fellow Swiss artists Albert Müller and Paul Camenisch, both of whom had also been significantly influenced by Kirchner and the broader Expressionist movement. Werner Neuhaus later joined the group.

"Rot-Blau" aimed to champion Expressionist art in Switzerland, providing a platform for artists who felt alienated by the more conservative art establishment. The group sought to organize exhibitions, create opportunities for its members, and foster a sense of shared artistic purpose. Their name, "Red-Blue," likely alluded to the expressive and symbolic use of strong primary colors, a characteristic feature of Expressionist painting. The group's formation was a significant moment for Swiss modernism, signaling a conscious effort to connect with international avant-garde currents while developing a distinctly Swiss inflection of Expressionism.

The artists of "Rot-Blau" shared a commitment to intense emotional expression, often depicting scenes of human interaction, landscapes imbued with psychological weight, and portraits that sought to capture inner turmoil. While Kirchner's influence was a common thread, each artist developed their own distinct voice. Scherer, with his powerful sculptures and woodcuts, brought a particular intensity and rawness to the group's output. The collaboration within "Rot-Blau" was dynamic, though not without its internal tensions. For instance, Paul Camenisch eventually distanced himself, partly to avoid direct competition with Scherer's increasingly prominent sculptural work. Despite its relatively short existence – Albert Müller died in 1926, and Scherer himself in 1927 – "Rot-Blau" played a crucial role in vitalizing the Swiss art scene.

Scherer's Artistic Language: Woodcuts and Sculptures

Hermann Scherer's primary contributions lie in his woodcuts and wooden sculptures. He produced over one hundred woodcuts and around twenty-five sculptures, a significant body of work for such a brief career. His approach to both media was characterized by a direct, almost primal engagement with the material.

In his woodcuts, Scherer employed bold, angular cuts, often leaving large areas of black and white in stark contrast, or using vibrant, flat planes of color in his color woodcuts. His technique was less about refined detail and more about capturing the essential energy and emotional core of his subjects. Works like Kastanienbäume (Chestnut Trees) demonstrate his ability to imbue landscape with a sense of raw, untamed vitality, the forms of the trees rendered with a vigorous, almost agitated energy. The influence of Kirchner is evident, but Scherer's hand is distinct in its robust, somewhat blockier forms. He shared with other Expressionists like Emil Nolde or Max Pechstein an interest in the expressive potential of the woodcut medium itself, allowing the grain of the wood and the gouges of the carving tool to contribute to the overall impact.

Scherer's sculptures, predominantly carved from wood, are perhaps his most powerful and original works. He favored a subtractive method, carving directly into the wood block, often leaving the figures deeply embedded within the original mass of the material. This technique, sometimes referred to as "Blockhaftigkeit" (block-like quality), emphasized the solidity and presence of the sculpture. His figures are often characterized by their elongated proportions, angular features, and intensely expressive postures and facial expressions. Works like Adam and Eve convey a profound sense of human vulnerability and interconnectedness, the figures intertwined yet seemingly locked in their own internal struggles. The surfaces are often rough-hewn, retaining the texture of the wood and the visible marks of the chisel, which adds to their raw power. This approach to sculpture aligns with the work of other Expressionist sculptors like Ernst Barlach, who also sought a direct, emotionally charged engagement with the medium of wood.

Dominant Themes in Scherer's Oeuvre

The thematic concerns in Hermann Scherer's art are deeply rooted in the human experience, often exploring states of intense emotion and existential angst. His work reflects the anxieties and passions of a generation grappling with the aftermath of World War I and the societal shifts of the early 20th century.

A recurring theme is that of human relationships, particularly the complexities of love, desire, and companionship. Nackte Paare (Nude Couples) often depict figures in close, sometimes tense, proximity, exploring intimacy, vulnerability, and the inherent solitude within relationships. The mother and child motif, as seen in works like Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child) and Madonna, is another significant theme. These are not sentimental depictions but rather explorations of the primal bond, often tinged with a sense of burden or sorrow, reflecting a more profound, existential understanding of motherhood.

Suffering, loneliness, and fear are palpable in many of his works. Figures are often shown with contorted features, anguished expressions, or in postures of despair. Totenklage (Lamentation for the Dead) is a powerful example, conveying a universal sense of grief and loss through stark, expressive forms. This focus on the darker aspects of human existence aligns Scherer with the broader Expressionist preoccupation with inner turmoil and the psychological landscape. His figures often seem to be wrestling with internal conflicts, their bodies and faces reflecting these struggles.

Even his landscapes, like the aforementioned Kastanienbäume, are not mere depictions of nature but are imbued with an emotional charge, reflecting an inner state rather than an objective reality. This subjective approach to landscape was also characteristic of artists like Edvard Munch, a key precursor to Expressionism, whose landscapes often mirrored his own psychological states.

Notable Works and Artistic Style

Several works stand out in Hermann Scherer's oeuvre, encapsulating his artistic vision and technical prowess.

Kastanienbäume (Chestnut Trees), a woodcut, showcases his dynamic approach to landscape. The trees are not rendered with botanical accuracy but are transformed into writhing, energetic forms that seem to pulse with life. The stark contrasts and bold lines create a sense of drama and raw natural power.

The sculpture Adam and Eve is a quintessential example of his figural work in wood. The two figures are carved from a single block, emphasizing their inseparable connection. Their forms are simplified and angular, their expressions conveying a mixture of innocence, apprehension, and the weight of their shared destiny. The direct carving technique and the retention of the wood's texture contribute to the work's primal intensity.

Totenklage (Lamentation for the Dead), likely a woodcut or sculpture series, would have explored themes of grief and mourning with Scherer's characteristic emotional directness. Such works often featured figures in postures of extreme sorrow, their bodies contorted by the weight of their loss.

Paintings and woodcuts titled Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child) or Madonna explore this traditional theme through an Expressionist lens. Scherer's interpretations often highlight the intensity of the maternal bond, sometimes with an undercurrent of anxiety or suffering, moving beyond idealized representations to explore the rawer emotional realities.

His depictions of Nackte Paare (Nude Couples) delve into the complexities of human intimacy. The figures are often intertwined, their bodies rendered with a stark honesty that emphasizes both their connection and their individual isolation. The raw energy of these works speaks to the passionate and often tumultuous nature of human relationships.

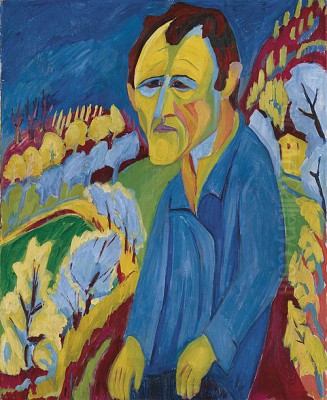

A portrait like Otto Steiger demonstrates his ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the psychological presence of the sitter, a hallmark of Expressionist portraiture also seen in the works of Oskar Kokoschka or Egon Schiele.

Scherer's style is characterized by its boldness and directness. He utilized bright, often clashing colors in his paintings and colored woodcuts, and his forms, whether in two or three dimensions, were typically angular, simplified, and emotionally charged. There is a deliberate rejection of academic refinement in favor of a more immediate and visceral form of expression.

Political Engagement and Personal Experiences

Beyond his studio practice, Hermann Scherer was not entirely detached from the social and political currents of his time. He is known to have designed a cover and posters for the magazine Der Kommunist, indicating a sympathy with leftist political ideas, a stance not uncommon among avant-garde artists of the period who sought radical societal change alongside artistic revolution.

His involvement in the Basel art scene also extended to practical matters. He participated in the planning of exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Basel, one of Switzerland's leading contemporary art institutions. It was here, in 1920, that he first exhibited his own works, marking his public debut as an independent artist.

An interesting, though perhaps less central, aspect of his biography is a reported mystical or religious experience. During a stay in Madeira, presumably for health reasons, Scherer is said to have experienced a form of miraculous healing at the São Salvador church. He apparently documented this experience, exploring themes of the supernatural. While his art is not overtly religious in a traditional sense, this experience might have contributed to the profound spiritual and existential questioning evident in his work.

Declining Health and Untimely Death

Tragically, Hermann Scherer's promising career was cut short by ill health. He suffered from chronic respiratory problems, including emphysema and asthma. These conditions likely exacerbated the physical demands of his sculptural work. Despite his illness, he continued to produce art with a remarkable intensity.

Hermann Scherer died on May 13, 1927, in Basel, from sepsis (blood poisoning). He was only 34 years old. His death, along with the death of Albert Müller the previous year, dealt a severe blow to the "Rot-Blau" group and to the burgeoning Swiss Expressionist movement.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Despite his short life, Hermann Scherer is recognized as one of the most important figures of Swiss Expressionism. His work brought a raw power and emotional depth to the Swiss art scene, strongly influenced by German Expressionism but possessing its own distinct character. He successfully translated the intensity of "Die Brücke" into a Swiss context, particularly through his powerful wood sculptures and woodcuts.

His association with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was undoubtedly formative, but Scherer was not merely an imitator. He absorbed Kirchner's influence and forged a personal style that was robust, direct, and deeply expressive. The "Rot-Blau" group, which he co-founded, was a vital catalyst for modern art in Switzerland, even if its existence was brief.

Today, Scherer's works are held in significant public collections, notably the Kunstmuseum Basel and the Bündner Kunstmuseum in Chur, which also has a strong collection of works by Kirchner and other artists associated with Davos. The Dordrechter Museum in Basel is also cited as holding a substantial number of his pieces. While perhaps less internationally renowned than his German counterparts like Kirchner, Heckel, or Nolde, or even Austrian Expressionists like Schiele or Kokoschka, Scherer's contribution to the broader Expressionist movement, and particularly to its Swiss manifestation, is undeniable.

His art continues to resonate with its unflinching exploration of the human condition – its joys, sorrows, anxieties, and passions. The raw energy and emotional honesty of his sculptures and prints ensure his place as a compelling and significant artist of the early 20th century. His legacy is that of an artist who, in a tragically brief period, burned brightly, leaving behind a body of work that speaks powerfully of the expressive urgencies of his time. He stands alongside other Swiss modernists like Cuno Amiet (who also experimented with Expressionist color) or even the slightly later Alberto Giacometti (whose early work also shows Expressionist tendencies, though he moved in a different direction) as a testament to the vitality of Swiss art in the modern era.