Gerard David stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Northern Renaissance art. Active during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, he is often celebrated as the last great master of the Bruges school of painting, a tradition luminous with talents like Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling. David's work forms a bridge between the established Netherlandish traditions of the fifteenth century and the emerging styles of the sixteenth, characterized by its brilliant colour, serene compositions, and profound emotional depth, particularly in religious subjects. Born around 1460 and passing away in 1523, his life and career unfolded during a period of significant artistic and cultural transition in Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gerard David was born in Oudewater, a town now located in the province of Utrecht in the Netherlands, around the year 1460. Details about his early life and initial artistic training remain somewhat scarce. However, art historians speculate that he may have received his formative training in Haarlem, another significant Dutch artistic centre. It is possible that he studied under Albert van Ouwater, a notable painter active in Haarlem known for his refined technique and contribution to early Dutch painting. This early exposure in the Northern Netherlands likely shaped David's initial approach to art, grounding him in the region's distinct traditions before his move south.

The artistic environment of Haarlem, while perhaps less internationally renowned than Bruges or Ghent at the time, possessed its own character. Training there would have exposed David to a particular strand of Netherlandish realism, potentially influencing his later meticulous attention to detail and texture. Whatever the specifics of his early training, it provided a foundation upon which he would build a remarkably successful career upon relocating.

Arrival and Prominence in Bruges

In 1483, Gerard David made a decisive move, relocating to Bruges, the wealthy and cosmopolitan heart of Flanders and a major centre for the arts and commerce in Northern Europe. This move marked the beginning of the most significant phase of his career. Almost immediately upon arrival, in 1484, he was accepted as a master into the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke, the official organization for painters and other artists in the city. Membership in the guild was essential for establishing an independent workshop and accepting commissions.

David quickly established a reputation in Bruges. His skill and artistic vision resonated with the city's patrons, and he rose through the ranks of the local art scene. His success was such that he became one of the city's leading painters, inheriting the mantle previously held by the highly respected Hans Memling, who died in 1494. David's prominence was formally recognized in 1501 when he was elected Dean of the Guild of Saint Luke, a position of considerable honour and responsibility, reflecting his high standing among his peers. Bruges would remain his primary base of operations for the rest of his life.

He also established a workshop in Antwerp around 1515, indicating his reach and reputation extended beyond Bruges, tapping into the burgeoning economic and artistic power of Antwerp in the early 16th century. Operating workshops in both cities allowed him to cater to a wider clientele and potentially engage with the newer artistic trends developing in Antwerp.

Artistic Style and Influences

Gerard David's art is renowned for its synthesis of tradition and subtle innovation. His style is deeply rooted in the Early Netherlandish tradition, characterized by meticulous detail, rich textures, and a profound sense of realism. However, he imbued this tradition with a unique sensibility, marked by serene compositions, a masterful use of colour, and a quiet, introspective emotional depth. His works often convey a sense of calm monumentality and spiritual gravity.

Mastery of Color: David was particularly celebrated for his handling of colour. Often described as a "master of colour," he employed a palette that was both brilliant and harmonious. His use of rich, saturated hues, combined with subtle modulations of light and shadow, created atmospheres that were simultaneously vibrant and tranquil. Warm tones often dominate, contributing to the gentle, dreamlike quality found in many of his devotional paintings. This exceptional skill with colour set him apart even within the colour-rich tradition of Netherlandish painting.

Netherlandish Heritage: David's work clearly shows the influence of the great masters who preceded him in Bruges and the wider Netherlandish region. The legacy of Jan van Eyck, with his groundbreaking oil painting techniques and unparalleled realism, is evident in David's attention to detail and surface texture. The influence of Rogier van der Weyden can perhaps be detected in the emotional resonance of his figures, while the work of Hugo van der Goes may have informed his compositional strategies and figure types.

Most significantly, David absorbed and adapted the style of Hans Memling, his immediate predecessor as Bruges' leading painter. He built upon Memling's elegant compositions and gentle piety, refining this approach with his own distinct colour sense and perhaps a slightly more robust, sculptural quality in his figures. David effectively consolidated the Bruges artistic tradition, drawing upon the achievements of Van Eyck and Memling to forge his own mature style.

Innovation and Italian Influence: While firmly grounded in the Netherlandish school, David's work also shows an awareness of broader artistic currents, including subtle influences from the Italian Renaissance. This is not overt in the manner of some contemporaries who travelled south, but can be seen in the balanced compositions, the solid, almost classical feel of some figures, and an increasing interest in landscape as more than just a backdrop. His innovation often lay in his fresh interpretation of traditional themes and his pioneering approach to landscape painting, where nature begins to play a more integrated and atmospheric role.

Major Works and Themes

Gerard David's surviving oeuvre consists primarily of religious paintings, including large altarpieces, smaller devotional panels, and portraits often incorporated into religious scenes. His work consistently reflects the deep piety of the era, yet often presents sacred figures with a relatable humanity.

Religious Paintings: Central to his output are numerous depictions of the Virgin and Child, a theme he returned to throughout his career. Works like The Virgin and Child with Saints and Angels (now in Rouen), dated 1509, exemplify his mature style. This large panel showcases his ability to organize complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and grace, bathing the scene in harmonious colour and serene light. The figures possess a quiet dignity and inner calm that became a hallmark of his art.

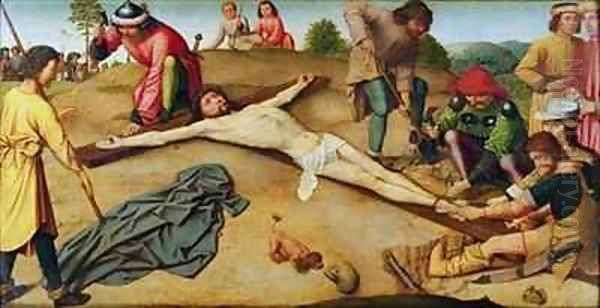

Other significant religious works include The Marriage of St. Catherine, a mystical theme popular in the period, which David rendered with characteristic sensitivity and rich detail. His Christ Nailed to the Cross presents the Passion narrative with solemnity and restrained emotion, focusing on the spiritual gravity of the event rather than overt, dramatic anguish. The Baptism of Christ triptych is another major work, notable for its detailed landscape background which integrates seamlessly with the central religious event. Scenes like The Virgin Embracing the Dead Christ (a Pietà or Lamentation) demonstrate his skill in conveying profound sorrow with dignity and tenderness. The Virgin among the Virgins (1509, Rouen) is another key example of his large-scale devotional work.

The Judgement of Cambyses: Perhaps David's most famous single commission is the pair of large panels known as The Judgement of Cambyses, completed in 1498 for the Alderman's Chamber in the Bruges Town Hall. These paintings depict a gruesome story from the ancient Greek historian Herodotus: the Persian king Cambyses II ordering the corrupt judge Sisamnes to be flayed alive for accepting a bribe. The first panel shows the arrest of Sisamnes, while the second, unflinchingly graphic panel depicts the flaying itself.

These works were intended as a justice panel or exemplum iustitiae, serving as a stark warning to the magistrates who conducted their business in the chamber to remain impartial and incorruptible. The panels are remarkable not only for their grim subject matter but also for David's skillful handling of narrative, complex composition, and detailed realism, even amidst the horror of the scene. They remain powerful examples of didactic art in the late medieval and early Renaissance period.

Landscape Painting: Gerard David made significant contributions to the development of landscape painting in the North. While earlier Netherlandish artists like Van Eyck had included detailed landscape backgrounds, David often gave the landscape a more prominent and atmospheric role. In works like the wings of the Transfiguration altarpiece or the background of the Baptism of Christ, the landscape unfolds with a sense of depth and continuity. He showed a keen observation of nature, depicting trees, rocks, and water with care. These panoramic vistas, often imbued with a peaceful, idyllic quality, anticipate the independent landscape paintings that would flourish in the sixteenth century with artists like Joachim Patinir.

Manuscript Illumination: Beyond panel painting, Gerard David was also active as a manuscript illuminator, contributing miniatures to luxurious illuminated books. His work in this medium reflects the same high quality of craftsmanship, refined detail, and rich colour seen in his larger paintings. This activity further highlights his versatility and his engagement with different facets of artistic production in Bruges.

Workshop, Pupils, and Followers

Like most successful masters of his time, Gerard David operated a busy workshop to meet the demand for his paintings. He employed assistants and trained pupils who helped produce works in his style. The existence of multiple versions of some of his compositions suggests the use of standardized patterns or cartoons within the workshop, allowing for efficient replication of popular designs. His workshops in both Bruges and Antwerp would have been centres of production and training.

While Hans Memling was a predecessor whose style influenced David, David himself trained or influenced the next generation of Bruges painters. Among his most notable followers were Adriaen Isenbrant and Ambrosius Benson. Both artists successfully continued working in Bruges after David's death, largely perpetuating his stylistic formulas, albeit often with less of the master's profound subtlety. Their work ensured the continuation of the Bruges tradition, heavily indebted to David, well into the sixteenth century.

Another artist associated with David is Albrecht Cornelis. Archival records suggest interactions between David's workshop and these artists. An anecdote recorded in guild documents describes a dispute involving Ambrosius Benson upon leaving David's workshop. Benson apparently took patterns and possibly unfinished works belonging to David, some of which had been borrowed from Adriaen Isenbrant's studio. These materials were later reportedly borrowed by Albrecht Cornelis. This incident offers a rare glimpse into the practical workings and sometimes contentious relationships within the Bruges artistic community, involving the circulation and ownership of artistic designs.

Connections with Contemporaries and Wider Influence

Gerard David's art was situated within a rich network of artistic exchange and influence. As discussed, he absorbed the legacy of Netherlandish pioneers like Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes, and Hans Memling. His own work, in turn, exerted influence on his contemporaries and successors.

His innovative approach to landscape was particularly impactful. Joachim Patinir, often credited as one of the first specialist landscape painters in the North, seems to have drawn inspiration from David's expansive landscape settings. Patinir further developed the panoramic "world landscape" style, where vast, high-viewpoint vistas dominate the composition, often dwarfing the small narrative figures. While Patinir took landscape in a new direction, David's work provided an important precedent.

Jan Mabuse (also known as Jan Gossaert), another significant contemporary active in the Low Countries, was also influenced by David, particularly in his landscape treatments. Mabuse, who travelled to Italy and absorbed Renaissance ideas more directly, combined Netherlandish detail with Italianate forms and classical motifs. His complex landscape backgrounds, while different in spirit from David's serene views, show a shared interest in spatial depth and naturalistic detail that connects back to the broader Netherlandish tradition David represented. The influence likely flowed both ways, with David potentially responding to the newer trends represented by artists like Mabuse active in Antwerp.

The connection with the great German master Albrecht Dürer is more circumstantial but relevant. Dürer travelled to the Low Countries in 1520-1521 and recorded his admiration for the works of past Netherlandish masters like Van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. While there's no record of him meeting David (who died shortly after Dürer's visit), Dürer would certainly have been aware of the leading Bruges master's work. Both artists, in their respective contexts, grappled with integrating Italian Renaissance principles (like perspective and proportion) with their native Northern traditions. Dürer's own sophisticated compositions and detailed realism share a common ground with the Netherlandish school exemplified by David.

Later Reputation and Rediscovery

Despite his prominence during his lifetime, Gerard David's fame gradually faded after the seventeenth century. As artistic tastes shifted, the quiet intensity and detailed realism of the Early Netherlandish masters fell out of fashion. For a considerable period, his work was overlooked or sometimes misattributed.

However, the nineteenth century witnessed a renewed interest in Northern European art history and a scholarly rediscovery of the "Flemish Primitives." Art historians began meticulously researching archives and re-examining paintings. Through the efforts of scholars like Gustav Waagen and James Weale, Gerard David's identity was re-established, his oeuvre reconstructed, and his significance recognized. His works were increasingly sought after by museums and collectors.

Today, Gerard David is firmly established in the canon of art history as a major figure of the Northern Renaissance. He is appreciated for his technical mastery, his exquisite use of colour, the serene beauty of his compositions, and his role as a crucial transitional artist who both summed up the achievements of the Bruges school and pointed towards future developments in Netherlandish art.

Unresolved Questions and Scholarly Debates

Despite the progress in understanding Gerard David's life and work, some questions and debates remain among art historians. The lack of signed and dated works for much of his career makes precise chronology and definitive attribution challenging in some cases. While a core body of work is securely attributed to him, the status of certain peripheral paintings continues to be discussed.

The exact role of workshop assistants in the production of paintings attributed to David is another area of ongoing research. Technical analysis, particularly using Infrared Reflectography (IRR) to reveal underdrawings, provides valuable insights into his working methods and the possible division of labour within the workshop. These studies help differentiate between the master's hand and that of his assistants but can also raise new questions about collaboration and production practices.

The nature and extent of Italian influence on his art remain subjects of interpretation. Similarly, the precise dynamics of his relationship with contemporaries like Isenbrant, Benson, and Cornelis are not fully understood, relying often on limited documentary evidence and stylistic comparisons. The market demand for his work and the resulting production of copies and variants further complicate questions of authenticity and attribution for certain pieces.

Legacy and Conclusion

Gerard David's legacy is substantial. As the last great painter of the Bruges school, he brought the city's remarkable artistic flourishing, initiated by Jan van Eyck nearly a century earlier, to a dignified close. His art represents a culmination of the Early Netherlandish style, characterized by its meticulous realism, luminous colour, and deep spiritual feeling. He successfully synthesized the innovations of his predecessors, particularly Van Eyck and Memling, into a distinctive style marked by calm monumentality and harmonious beauty.

His contributions extended beyond consolidating tradition. His innovative treatment of landscape played a significant role in its evolution towards an independent genre. His workshop trained artists who carried his influence into the sixteenth century, ensuring the continuity of the Bruges style even as the city's economic and artistic dominance began to wane in favour of Antwerp.

Today, Gerard David's paintings are admired in major museums around the world. They continue to captivate viewers with their technical brilliance, their serene and contemplative mood, and their quiet emotional power. He remains a key figure for understanding the rich artistic landscape of the Northern Renaissance, an artist whose work embodies both the culmination of a great tradition and the subtle beginnings of new artistic paths. His mastery of colour, his sensitive portrayal of religious themes, and the enduring beauty of his art secure his place as one of the most important painters of his era.