Sano di Pietro, born Ansano di Pietro di Mencio in 1406, stands as one of the most prolific and characteristic painters of the Sienese School during the Early Renaissance, or Quattrocento. Active primarily in his native Siena until his death in 1481, Sano's artistic journey encapsulates the enduring traditions of Sienese art while subtly reflecting the evolving artistic currents of 15th-century Italy. His vast oeuvre, dominated by devotional images of the Madonna and Child, saints, and narrative religious scenes, is celebrated for its gentle piety, vibrant coloration, and exquisite decorative qualities. While sometimes overshadowed by the more radical innovations of his Florentine contemporaries, Sano di Pietro's contribution was crucial to maintaining Siena's distinct artistic identity and satisfying the profound spiritual needs of his community.

The Cradle of Sienese Art: Early Life and Influences

Sano di Pietro emerged into an artistic environment rich with a distinctive local heritage. Siena, a powerful and prosperous city-republic, had cultivated a unique artistic tradition that, while aware of developments elsewhere, often prioritized lyrical beauty, elegant linearity, and a deep-seated conservatism rooted in Byzantine and Gothic aesthetics. Masters like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the brothers Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Pietro Lorenzetti had, in the 13th and early 14th centuries, established a Sienese "dialect" of painting renowned for its emotional resonance, refined craftsmanship, and opulent use of gold and color.

It was into this legacy that Sano di Pietro was initiated. The precise details of his earliest training are not definitively documented, but by 1428, he was enrolled in the Sienese painters' guild (the Società dei Pittori), a clear indication of his professional standing. Art historical consensus strongly points to Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni) as Sano's principal master. Sassetta, himself a leading figure of the Sienese Quattrocento, was known for his delicate figures, narrative clarity, and a style that gracefully blended International Gothic elegance with emerging Renaissance sensibilities. Sano's early works clearly bear the imprint of Sassetta's tutelage, evident in the elongated figures, gentle expressions, and the meticulous rendering of detail. He is believed to have worked as an assistant in Sassetta's workshop, a common practice that would have provided him with invaluable hands-on experience in all aspects of panel painting, from preparing wooden supports to the final application of tempera and gold leaf.

Forging an Artistic Identity

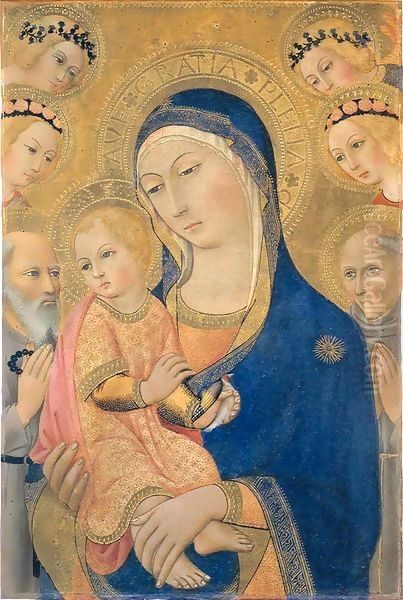

While Sassetta's influence was formative, Sano di Pietro gradually developed his own distinct artistic voice. His style, though always retaining a certain Sienese sweetness and decorative charm, evolved over his long and productive career. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of the Virgin Mary, often portrayed with a serene, almost dreamlike tenderness. These Madonnas, whether enthroned in majesty or in more intimate portrayals with the Christ Child, became a hallmark of his production.

Sano's paintings are characterized by their luminous, often jewel-like colors. He favored bright blues, rich reds, and delicate pinks, frequently set against shimmering gold backgrounds that enhanced the otherworldly and sacred nature of his subjects. His compositions, while generally adhering to established iconographic conventions, demonstrate a sure sense of design and a concern for harmonious arrangement. The figures, though not possessing the anatomical rigor or volumetric solidity pursued by Florentine innovators like Masaccio or Donatello, convey a quiet dignity and spiritual grace. There is a pervasive atmosphere of calm, piety, and serene devotion in his works, appealing directly to the contemplative needs of his patrons.

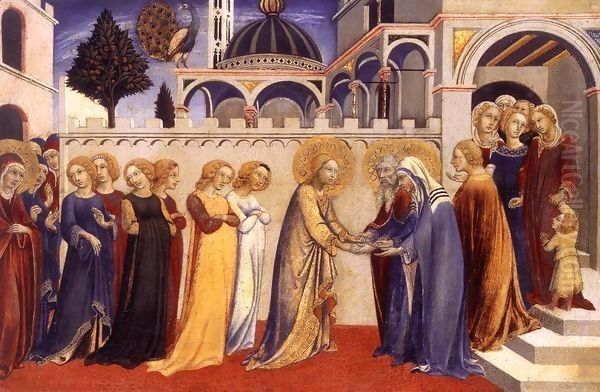

His output was diverse, encompassing large-scale altarpieces for churches and confraternities, smaller panels for private devotion, manuscript illuminations, and even designs for banners and cassone (marriage chest) panels. This versatility speaks to the high demand for his work and the breadth of his workshop's capabilities.

Major Themes and Iconic Representations

The Madonna and Child was undoubtedly Sano di Pietro's most recurrent theme. He explored numerous variations, from the Madonna of Humility (seated on the ground) to the majestic Maestà (Madonna enthroned as Queen of Heaven), often flanked by angels and saints. These works, such as the Madonna and Child now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, exemplify his ability to convey both maternal tenderness and divine grace. The Madonna and Saints, like the example in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, and the Madonna and Saints with Angels, housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris, further showcase his skill in composing multi-figure altarpieces, where each saint is identifiable by their traditional attributes.

Saint Bernardino of Siena, a charismatic Franciscan preacher and reformer who was canonized in 1450, became another significant subject for Sano. The artist produced numerous images of the saint, including the iconic Portrait of St. Bernardino, which helped to codify the saint's visual representation, often showing him holding a tablet with the IHS Christogram. One such notable depiction is the Predica di San Bernardo in Piazza del Campo (Sermon of St. Bernardino in the Piazza del Campo), which captures a key moment in Sienese religious life.

Narrative scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary also feature prominently in his oeuvre. The Annunciation, such as the panel in the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the Adoration of the Child (Mead Art Museum, Amherst College), and the Baptism of Christ (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) demonstrate his capacity for storytelling, albeit with a characteristic Sienese emphasis on lyrical grace rather than dramatic intensity. The Crucifixion of St. John the Baptist (Uffizi Gallery, Florence) and The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) are further examples of his narrative skill, often forming parts of predella panels or larger altarpiece complexes. Other works like The Purification of the Virgin and the Return of the Virgin (whose specific current primary location for a major Sano work is less consistently cited than others, though versions exist in various collections) also highlight his engagement with the full spectrum of Christian iconography.

The Prolific Workshop and Notable Commissions

Sano di Pietro ran a highly organized and exceptionally productive workshop. This was essential to meet the considerable demand for his art from churches, religious orders (particularly the Franciscans and Dominicans), confraternities, and private citizens throughout Siena and its surrounding territories. The sheer volume of works attributed to Sano and his workshop is a testament to his success and efficiency. While this sometimes led to a degree of standardization or repetition in certain compositions, the overall quality of execution remained remarkably high.

One of his most significant commissions was the polyptych for the church of the Gesuati (Poor Hermits of Saint Jerome) in Siena, completed around 1444. Often referred to as the Polittico dei Gesuati, its central panel typically depicts the Madonna and Child with Angels, surrounded by saints such as Jerome, John the Baptist, Bernardino, and Bartholomew. This altarpiece is a prime example of Sano's mature style, showcasing his mastery of color, refined detail, and serene devotional atmosphere. It is now housed in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.

Another important public commission was the fresco of the Coronation of the Virgin (sometimes referred to as the Assumption of the Virgin) in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena's town hall. This work, painted in 1445, placed Sano firmly within the tradition of Sienese civic patronage, following in the footsteps of artists like Simone Martini who had also decorated this prestigious seat of government. His involvement in manuscript illumination, such as for choir books for the Siena Cathedral, further demonstrates the range of his artistic activities.

Sano and His Contemporaries: A Sienese Constellation

Sano di Pietro's career unfolded alongside other notable Sienese artists. His relationship with Sassetta was foundational, and it is even believed that Sano completed some works left unfinished at Sassetta's death in 1450, such as parts of the Sansepolcro Altarpiece. This act of completing a master's work was a common practice and a mark of respect and continuity.

Giovanni di Paolo, another leading Sienese painter of the Quattrocento, was a contemporary whose artistic path sometimes paralleled and sometimes diverged from Sano's. While both were influenced by Sassetta and shared a commitment to Sienese artistic traditions, Giovanni di Paolo's style was often more idiosyncratic, characterized by a more intense emotionalism, elongated figures, and imaginative, sometimes fantastical, landscape settings. Comparing their respective outputs reveals the diversity within the Sienese school itself.

Other Sienese artists active during Sano's lifetime included Domenico di Bartolo, known for his narrative frescoes in the Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala, and Vecchietta (Lorenzo di Pietro), a versatile artist who worked as a painter, sculptor, and architect. While Sienese art maintained its distinct character, it was not entirely isolated. The influence of International Gothic artists like Gentile da Fabriano, who had worked in various Italian centers, could be felt in the decorative richness and elegant lines of Sienese painting.

The artistic climate in Florence, with its emphasis on perspective, humanism, and classical antiquity, as championed by figures like Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and painters such as Masaccio, Fra Angelico, and Piero della Francesca, offered a different path. Fra Angelico, a Dominican friar, shared with Sano a profound religious sincerity and a love for radiant color, though his figures possessed a greater naturalism and spatial awareness rooted in Florentine innovations. Sano's art, by contrast, remained more closely tied to the spiritual and aesthetic priorities of Siena, prioritizing devotional efficacy and lyrical beauty over scientific naturalism. Artists like Domenico Veneziano, working in Florence, were exploring effects of light and color that, while different in intent, show the broader Quattrocento fascination with the expressive potential of the palette.

Later Career, Personal Life, and Enduring Reputation

Sano di Pietro continued to be highly productive throughout his later career. While some critics have suggested that his style became somewhat more formulaic in his later years, likely due to the extensive involvement of his workshop in fulfilling numerous commissions, the demand for his characteristic gentle Madonnas and serene saints never waned. His ability to consistently produce works that resonated with the devotional sensibilities of his patrons ensured his continued success.

Beyond his artistic endeavors, glimpses into Sano's personal life suggest a man well-integrated into Sienese society. He was married and a father, and records indicate he was a successful businessman, acquiring property and managing his workshop effectively. His deep religious faith, so evident in his art, was also a defining feature of his character. An epitaph reportedly recorded his identity as "famosus pictor et homo omnium Dei" (a famous painter and a man entirely of God), underscoring the fusion of his artistic vocation and his spiritual life.

Sano di Pietro passed away in 1481, leaving behind a remarkable artistic legacy. He was buried in the church of San Domenico in Siena, a testament to his standing within the community.

Critical Reception and Lasting Legacy

In the 19th century, Sano di Pietro was highly esteemed, often seen as the quintessential Sienese painter of his era, embodying the school's perceived purity and spiritual grace. However, 20th-century art criticism, particularly under the influence of scholars like Bernard Berenson who championed the intellectual rigor and innovation of Florentine art, sometimes viewed Sano's work as charming but somewhat retardataire or lacking in groundbreaking development. This perspective often highlighted his adherence to established formulas and a perceived lack of engagement with the more "progressive" aspects of Renaissance art.

More recent scholarship, however, has tended towards a more balanced appreciation of Sano's achievements. While acknowledging his conservatism relative to Florence, art historians now emphasize the intrinsic qualities of his work: the exquisite craftsmanship, the harmonious use of color, the genuine piety, and the profound understanding of his patrons' spiritual needs. His art perfectly fulfilled its intended function within Sienese society, providing objects of devotion that were both beautiful and spiritually efficacious.

Sano's influence extended to the next generation of Sienese painters, including artists like Matteo di Giovanni and Neroccio de' Landi, who continued to work in a style that, while incorporating newer elements, retained a characteristically Sienese elegance and devotional intensity. Today, Sano di Pietro's paintings are found in major museums and collections across the globe, from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena and the Uffizi in Florence to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the Louvre in Paris. These works continue to enchant viewers with their serene beauty and offer a precious window into the spiritual and artistic world of 15th-century Siena.

Conclusion: The Enduring Light of Sano di Pietro

Sano di Pietro was more than just a prolific painter; he was a cornerstone of Sienese artistic identity in the Quattrocento. His unwavering commitment to the devotional function of art, combined with his innate sense of color, line, and composition, resulted in a body of work that, while perhaps not revolutionary in the Florentine sense, possesses an enduring appeal. He masterfully balanced the rich artistic heritage of Siena with the demands of his time, creating images that were both traditional and deeply personal in their gentle spirituality. His art speaks to a world where faith and beauty were inextricably linked, and his luminous Madonnas and serene saints continue to radiate a quiet, contemplative grace that transcends the centuries. Sano di Pietro remains a testament to the enduring power of an artistic vision rooted in sincere faith and exquisite craftsmanship, a true luminary of the Sienese school.