Giacomo Francia (c. 1486–1557) stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure in the rich tapestry of the Italian Renaissance, particularly within the artistic crucible of Bologna. Born into an artistic dynasty, he was the son of the highly esteemed painter and goldsmith Francesco Francia, a dominant force in Bolognese art at the turn of the sixteenth century. Giacomo's life and career were inextricably linked with his father's formidable reputation and the bustling workshop he inherited. While he diligently upheld the family's artistic traditions, Giacomo also carved out his own identity, contributing a body of work characterized by serene piety and refined craftsmanship that resonated with the devotional needs of his time.

His artistic journey began under the direct tutelage of his father, alongside his brother Giulio Francia. This familial apprenticeship was typical of Renaissance workshops, where skills were passed down through generations, ensuring continuity of style and technique. The Francia workshop was a hub of activity, producing altarpieces, devotional panels, and portraits for a discerning clientele that included religious orders, noble families, and civic institutions. Giacomo absorbed not only the painterly techniques but also the meticulous attention to detail that stemmed from his father's origins as a goldsmith – a precision that often translated into a smooth, enamel-like finish in their paintings.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in the Francia Workshop

Giacomo Raibolini, known as Giacomo Francia, was born in Bologna around 1486. His father, Francesco Raibolini (c. 1450–1517), better known as Francesco Francia, was already a preeminent artist in the city, celebrated for his gentle Madonnas, his technical finesse, and his leadership in the Bolognese school. Francesco's early training as a goldsmith and medallist deeply informed his painting style, lending his works a characteristic clarity, polished surfaces, and a certain metallic sheen in the rendering of drapery and flesh tones. It was within this environment of high craftsmanship and artistic innovation that Giacomo and his younger brother Giulio (c. 1487–1540) received their formative training.

The Francia workshop was not merely a place of instruction but a collaborative enterprise. The brothers would have started with rudimentary tasks, grinding pigments, preparing panels, and copying their father's drawings and paintings. As their skills developed, they would have progressed to painting less critical sections of commissioned works, eventually becoming trusted assistants capable of executing entire pieces under Francesco's supervision or in his style. This collaborative nature often makes it challenging for art historians to definitively distinguish the individual hands of Francesco, Giacomo, and Giulio in works produced during Francesco's lifetime, particularly in larger, complex altarpieces.

Francesco Francia's style itself was an amalgamation of influences. He was receptive to the lyrical grace of Perugino (Pietro Vannucci), whose works were known in Bologna, and the harmonious classicism of the early Raphael Sanzio da Urbino, who would later become a towering figure of the High Renaissance. Lorenzo Costa, a Ferrarese painter who collaborated with Francesco for many years in Bologna, also played a role in shaping the artistic milieu from which Giacomo emerged. These influences, characterized by balanced compositions, sweet facial expressions, and a gentle devotional sentiment, became hallmarks of the Francia workshop style, which Giacomo would largely perpetuate.

Upon Francesco Francia's death in 1517, Giacomo and Giulio jointly inherited the workshop and its considerable reputation. They continued to operate under the Francia name, fulfilling existing commissions and securing new ones. It is generally believed that Giacomo, being the elder and perhaps more prolific, took the leading role in the partnership. Their collaborative works from this period often bear the signature "I FRANCIA" or similar, indicating their joint authorship. They maintained the workshop's high standards of craftsmanship and continued to produce works in the established Francia manner, which remained popular with Bolognese patrons.

Artistic Style: Continuity and Subtle Shifts

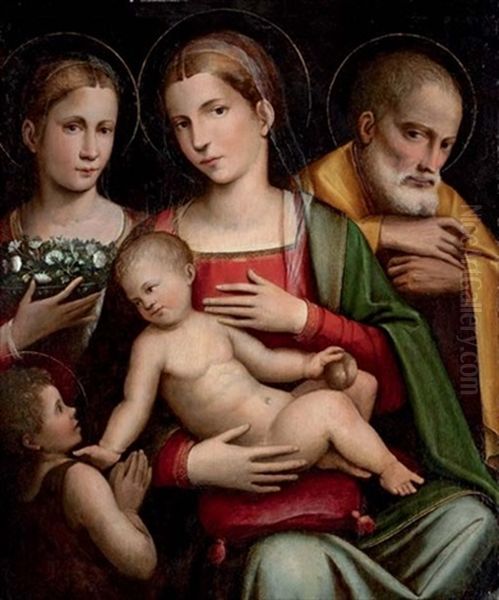

Giacomo Francia's artistic style is fundamentally rooted in the traditions established by his father. He embraced the elder Francia's penchant for serene, devout figures, harmonious compositions, and a soft, somewhat melancholic beauty. His Madonnas, like his father's, are typically depicted with gentle, downcast eyes, conveying humility and maternal tenderness. The figures are often characterized by a smooth, polished finish, and a careful, almost miniaturist attention to detail, especially in the rendering of hair, fabrics, and accessories. This meticulousness harks back to the goldsmith's precision that was a hallmark of Francesco Francia.

While continuity is a dominant feature, subtle distinctions can be observed in Giacomo's independent works. Some scholars note a slightly more robust quality in his figures compared to the ethereal grace of his father. His coloration can also differ, sometimes employing a cooler palette or a different harmony of hues. However, he largely eschewed the dramatic dynamism, intense chiaroscuro, and psychological complexity that were becoming characteristic of the High Renaissance in Rome and Florence, as exemplified by artists like Michelangelo Buonarroti or the mature Raphael. Instead, Giacomo remained committed to a more conservative, Quattrocento-inflected style that emphasized clarity, piety, and decorative appeal.

His compositions are generally well-balanced and clearly legible, often adhering to established iconographic conventions for religious subjects. He frequently painted Sacra Conversazione (sacred conversation) scenes, depicting the Madonna and Child flanked by saints, a popular format for altarpieces. In these works, the saints are individualized through their attributes and expressions, yet they coexist in a harmonious, contemplative atmosphere. The landscapes in his backgrounds, though often conventional, provide a serene setting for the sacred figures, typically featuring rolling hills, feathery trees, and distant blue mountains, reminiscent of Perugino's Umbrian vistas.

The influence of Florentine art, particularly the work of artists like Fra Bartolomeo, can be discerned in some of Giacomo's compositions, perhaps in a greater monumentality of figures or a more considered arrangement of groups. However, the core of his style remained deeply Bolognese, reflecting the city's somewhat conservative artistic tastes and its strong tradition of devotional painting. He was less an innovator than a skilled practitioner and consolidator of an established artistic language, one that found favor for its accessibility and its capacity to inspire piety.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Giacomo Francia's oeuvre consists predominantly of religious subjects, with a particular focus on depictions of the Madonna and Child, often accompanied by saints. These themes were in high demand for both public altarpieces and private devotional panels.

One of his most celebrated works is the Madonna and Child with Saint Joseph, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Augustine, and Saint Francis, also known as the Pala Felicini, originally painted for the Felicini Chapel in the church of San Francesco, Bologna, and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna. This altarpiece exemplifies his mature style, showcasing a balanced composition, serene figures, and a rich, harmonious color palette. The Virgin is centrally enthroned, her gentle gaze directed towards the Christ Child, while the attendant saints, each clearly identifiable, engage in a silent, devout communion.

Another significant work often attributed to him, or to the Francia workshop under his direction, is the Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Jerome. Works like these demonstrate his ability to create tender and accessible images of devotion. The interaction between the figures is typically gentle and understated, emphasizing the sacredness and humanity of the scene.

The Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist, now housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris, is another key example of his output. This painting showcases his characteristic soft modeling of forms, the delicate rendering of features, and the tranquil atmosphere that pervades his religious scenes. The young Saint John, a frequent figure in Renaissance art, is depicted in playful yet reverent interaction with the Christ Child, a theme that allowed for a touch of human warmth within the sacred context.

His Madonna del Rosario (Madonna of the Rosary) paintings, a theme that gained popularity in the 16th century, further illustrate his commitment to traditional devotional imagery. These works typically depict the Virgin bestowing the rosary upon Saint Dominic and Saint Catherine of Siena, surrounded by mysteries of the rosary. Giacomo's interpretations of this theme would have served as focal points for prayer and contemplation.

Beyond these larger altarpieces and significant devotional panels, Giacomo also produced numerous smaller works for private patrons. These often featured half-length figures of the Madonna and Child, sometimes with the infant Saint John or other saints. These more intimate paintings catered to the growing demand for personal devotional art among the laity. His portraits, though less numerous than his religious works, also followed the refined and somewhat idealized manner of his father.

The Francia Workshop: Collaboration and Legacy

The Francia workshop, under the joint direction of Giacomo and Giulio Francia after 1517, continued to be a dominant force in Bolognese art for several decades. The brothers often collaborated on commissions, and their individual styles, while distinguishable to a discerning eye, shared a strong family resemblance. This makes precise attribution a persistent challenge for art historians, particularly for works signed simply "FRANCIA" or with initials that could refer to either brother or their combined efforts.

Giulio Francia, while perhaps less prolific or less consistently in the limelight than Giacomo, was a capable painter in his own right. His style is often described as being somewhat softer and more delicate than Giacomo's, perhaps adhering even more closely to their father's late manner. The brothers' collaboration appears to have been largely harmonious, allowing them to manage a significant output and maintain the workshop's reputation for quality and reliability. They produced numerous altarpieces for churches in Bologna and surrounding towns, as well as devotional paintings for private patrons.

The workshop system, central to Renaissance art production, meant that assistants and pupils would also have contributed to the execution of paintings. While specific names of Giacomo's pupils are not as prominently recorded as those of his father (who famously taught Marcantonio Raimondi, the renowned engraver), it is certain that the workshop continued to train younger artists in the Francia tradition. This ensured the dissemination of their style and techniques within Bologna.

The legacy of the Francia workshop, therefore, extends beyond the individual contributions of Giacomo and Giulio. It represents a distinct Bolognese artistic tradition characterized by its gentle piety, technical refinement, and a certain conservative adherence to established forms, even as more dramatic and dynamic styles were emerging elsewhere in Italy. Artists like Innocenzo da Imola, also active in Bologna, shared some stylistic affinities with the Francia school, though he developed his own distinct manner, influenced more directly by Raphael. Amico Aspertini, another Bolognese contemporary, offered a more eccentric and expressive alternative to the classicism of the Francia.

Navigating the Shadow of Francesco Francia

A recurring theme in the assessment of Giacomo Francia's career is the comparison with his father. Francesco Francia was, by all accounts, a towering figure in Bolognese art, whose skill as both a goldsmith and painter earned him widespread acclaim. Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, praised Francesco, though he also recounted the famous, and likely apocryphal, story that Francesco died of despair after seeing Raphael's Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia, feeling his own art surpassed. While this tale is likely a romantic embellishment, it underscores the immense prestige Raphael's work held and the shifting artistic currents of the High Renaissance.

Giacomo, by inheriting his father's workshop and style, inevitably faced the challenge of living up to this formidable legacy. While he was a highly competent and respected artist, critical consensus generally holds that he did not surpass his father's achievements, nor did he radically innovate upon the established Francia manner. His adherence to a style rooted in the late Quattrocento and early Cinquecento, while ensuring continued patronage, placed him somewhat outside the mainstream of High Renaissance developments championed by figures like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, or Titian in Venice.

This is not to diminish Giacomo's own merits. His works possess a quiet dignity, a sincere devotional quality, and a consistent level of craftsmanship that made him a sought-after artist in Bologna. He successfully maintained the family workshop's prominence for many years, fulfilling the artistic needs of his community. His style, with its emphasis on clarity, grace, and piety, resonated with the religious sensibilities of many Bolognese patrons who may have preferred the familiar and reassuring qualities of the Francia tradition over more startling innovations.

The artistic environment of Bologna itself was somewhat conservative compared to Florence or Rome. While open to external influences, the city maintained a strong local school with its own distinct characteristics. Giacomo Francia was a key exponent of this local tradition, contributing significantly to the city's artistic heritage. His works can be found in many Bolognese churches and in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, a testament to his enduring local importance.

Later Career, Death, and Enduring Presence

Giacomo Francia remained active as a painter in Bologna throughout the first half of the 16th century. He continued to receive commissions for altarpieces and devotional paintings, adapting his style subtly over time but largely remaining true to the artistic principles inherited from his father. The Francia workshop, under his guidance, provided a steady stream of religious art that adorned churches and private chapels, shaping the visual landscape of devotion in the region.

His involvement with local artistic confraternities or guilds, though not extensively documented, would have been part of his professional life, contributing to the regulation and promotion of the arts in Bologna. The city's university, one of the oldest in Europe, fostered an intellectual environment that, while perhaps not directly impacting his style, contributed to Bologna's cultural vibrancy.

Giacomo Francia died in Bologna on January 5, 1557. By this time, new artistic trends were taking hold. The late Renaissance was giving way to Mannerism, with artists like Pellegrino Tibaldi making their mark in Bologna, and the Carracci brothers (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico) would soon revolutionize Bolognese painting, leading it towards the Baroque. Yet, the legacy of the Francia workshop, and Giacomo's role within it, remained a foundational element of the city's artistic history.

Today, Giacomo Francia's works are held in numerous museums and collections worldwide, including the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. While he may not be as universally recognized as some of his more famous Italian Renaissance contemporaries like Andrea del Sarto or Correggio, his paintings are valued for their gentle beauty, their technical refinement, and their embodiment of a specific moment in Bolognese art. They offer a window into the devotional practices and artistic tastes of 16th-century Bologna, representing a significant contribution to the rich artistic heritage of the Italian Renaissance. His career underscores the importance of workshop traditions, familial artistic dynasties, and the enduring appeal of art that speaks to sincere piety and quiet contemplation.