Giovanni Antonio Sogliani stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of Renaissance Florence. Active during the period often referred to as the High Renaissance and the early stirrings of Mannerism, Sogliani carved out a niche for himself as a painter of deeply felt religious subjects, characterized by their clarity, serene piety, and refined execution. His career, spanning the first half of the 16th century, saw him absorb the influences of his master and prominent contemporaries, yet develop a personal style that resonated with the devotional sensibilities of his patrons.

Early Life and Formative Apprenticeship

Born in Florence in 1492, Giovanni Antonio Sogliani entered a world where art was not merely decorative but a vital means of communication, civic pride, and spiritual expression. The city was still basking in the afterglow of artistic giants like Masaccio and Donatello, and witnessing the mature works of masters who would define the High Renaissance. Sogliani's artistic journey began in earnest when he entered the workshop of Lorenzo di Credi (c. 1459–1537). This was a pivotal association that would shape his technical skills and artistic outlook for many years.

Lorenzo di Credi himself was a product of the esteemed workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, a powerhouse of artistic training that also nurtured Leonardo da Vinci and Perugino. Credi was known for his meticulous technique, polished finish, and a somewhat conservative adherence to the Quattrocento ideals of clarity and grace, though he also absorbed some of the sfumato and atmospheric qualities popularized by Leonardo. Sogliani remained under Credi's tutelage for an extensive period, reportedly twenty-four years. This long apprenticeship indicates a deep bond and a thorough immersion in Credi's methods, which emphasized careful drawing, smooth application of paint, and a gentle, devotional quality in religious scenes.

This extended period in Credi's studio meant that Sogliani's early artistic identity was closely tied to that of his master. He would have learned the intricacies of panel painting, fresco technique, and the management of a workshop. The influence of Credi's style, with its emphasis on serene figures, balanced compositions, and often a bright, clear palette, is evident in Sogliani's earlier works.

Emergence as an Independent Master and Key Influences

By 1522, Sogliani had gained sufficient standing to be admitted into the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, the Florentine guild that painters belonged to. This marked his official recognition as an independent master. While his foundation was firmly rooted in Lorenzo di Credi's teachings, Sogliani's artistic vision began to expand as he engaged with the work of other leading Florentine painters. His style evolved, becoming richer and more complex, though always retaining a core of clarity and devotional sincerity.

Two of the most significant influences on Sogliani's mature style were Fra Bartolomeo (1472–1517) and Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530). Fra Bartolomeo, a Dominican friar based at the convent of San Marco, was a leading proponent of the High Renaissance style in Florence. His paintings are characterized by their compositional grandeur, monumental figures, harmonious color, and profound spiritual intensity. Sogliani appears to have absorbed Fra Bartolomeo's ability to imbue religious scenes with a sense of solemn dignity and emotional depth. The friar's mastery of light and shadow to create volume and atmosphere also left its mark.

Andrea del Sarto, known as "the faultless painter" for his technical perfection and graceful figures, was another towering figure in Florentine art. His work, celebrated for its rich color, soft sfumato, and elegant compositions, offered Sogliani a model of sophisticated High Renaissance classicism. Sogliani's paintings often reflect del Sarto's harmonious blending of figures and their environment, and a similar pursuit of refined beauty.

The pervasive influence of Leonardo da Vinci, though perhaps more indirectly felt through Lorenzo di Credi and the general artistic climate, also played a role. Leonardo's innovations in sfumato, psychological expression, and dynamic composition had transformed Florentine painting, and echoes of his approach can be discerned in Sogliani's subtle modeling and attempts to convey inner states.

It is also important to consider the broader artistic heritage of Florence. The clarity of form and perspective pioneered by artists like Masaccio, the lyrical grace of Fra Angelico (who also worked extensively at San Marco), and the sweet devotional style of painters like Perugino (Raphael's master), all formed part of the visual vocabulary Sogliani inherited and synthesized.

In 1531, Sogliani's loyalty to his former master was demonstrated when he became the executor of Lorenzo di Credi's will. This responsibility suggests a relationship built on trust and respect, extending beyond the typical master-pupil dynamic.

The Distinctive Style of Sogliani

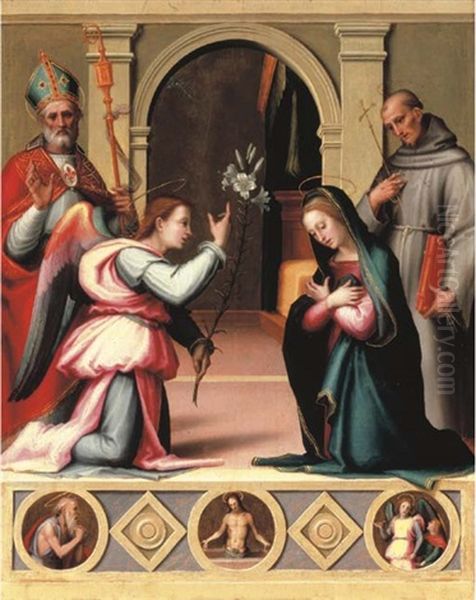

Giovanni Antonio Sogliani's mature artistic style can be described as a synthesis of these influences, filtered through his own temperament and devotional inclinations. He is often associated with the "maniera moderna," or modern manner, a term Vasari used to describe the art of the High Renaissance, but Sogliani’s interpretation was more conservative and less inclined towards the dramatic innovations that would lead to Mannerism.

His paintings are generally characterized by their clarity and legibility. Figures are well-defined, often with a gentle, almost sweet expression. Compositions are typically balanced and harmonious, avoiding excessive complexity or agitation. There is a pervasive sense of calm and piety in his work, making it particularly suitable for altarpieces and private devotional panels.

Technically, Sogliani was a skilled craftsman. He often employed soft modeling to render figures, avoiding the hard outlines of some earlier Quattrocento masters. His use of color could be both delicate and rich, often achieving a pleasing harmony. The provided information notes specific stylistic traits such as the "almost complete omission of contour lines," "dynamic lines defining curls and beards," "cross-hatched grid structures," and the "prominent use of white pigment." These details point to a painter attentive to the subtleties of surface and texture, using light and line to create form and visual interest. The aim was often to create a serene and elegant atmosphere, conducive to contemplation.

While he embraced the High Renaissance ideals of grace and naturalism, Sogliani generally shied away from the heroic dynamism of Michelangelo or the intellectual complexities that began to emerge with early Mannerist painters like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. His strength lay in a more direct and heartfelt expression of religious faith.

Major Works and Commissions

Sogliani's oeuvre consists primarily of religious subjects, executed as altarpieces, frescoes, and smaller panels for private devotion. His works were commissioned for important churches and convents, mainly in Florence but also in other Tuscan cities like Pisa.

One of his most celebrated works is the fresco of The Miraculous Supper of St. Dominic (also known as St. Dominic and his Friars Fed by Angels), painted in 1536 for the refectory of the Convent of San Marco in Florence. This large-scale work, depicting a key moment in the life of the founder of the Dominican order, is a testament to Sogliani's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and devotional impact. The choice of subject and its location in the friars' dining hall made it a particularly resonant piece, reinforcing the spiritual foundations of their communal life. The serene figures and the orderly composition reflect the influence of Fra Bartolomeo, who had also been closely associated with San Marco.

Another significant work mentioned is The Last Supper, located in the church of Anghiari. This theme, a cornerstone of Christian iconography, allowed Sogliani to explore the portrayal of individual apostles' reactions to Christ's words, a challenge met by many Renaissance masters, most famously Leonardo da Vinci. Sogliani's interpretation would likely have emphasized the solemnity and spiritual significance of the event.

His Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist is a representative example of a theme immensely popular during the Renaissance. Such paintings allowed artists to explore the tender relationship between mother and child, and the prophetic connection between Jesus and John. Sogliani's versions are noted for their gentle piety, graceful figures, and harmonious compositions, often showcasing his skill in rendering soft flesh tones and delicate expressions.

Sogliani also undertook commissions outside Florence. For the Pisa Cathedral, he painted an altarpiece of St. Rocco. St. Rocco was a popular plague saint, and commissions featuring him were common, especially in times of pestilence. This work demonstrates Sogliani's reputation extending beyond his native city.

Other works attributed to him or mentioned include a Nativity of Christ, a Miracle of St. Mark (which he may have completed as part of his duties as executor of Lorenzo di Credi's estate), and a St. Matthew's Miracle. These titles further underscore his focus on narrative religious scenes and depictions of saints. His works found homes in prominent Florentine churches such as San Lorenzo and the Duomo (Cathedral) of Pisa, indicating the esteem in which he was held.

Religious Devotion, Workshop Practice, and Character

The consistent focus on religious themes in Sogliani's work was not merely a matter of market demand; it appears to have been deeply rooted in his personal convictions. He was described by contemporaries, including Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Artists," as a man of good character, pious, and dedicated to his art. This personal piety undoubtedly informed the sincere and heartfelt quality of his religious paintings, which appealed to the devout laity and clergy of Florence.

Like most successful artists of his time, Sogliani would have maintained a workshop to assist him with commissions. The provided information mentions pupils such as Sandro del Calzino (also referred to as Sandrino) and Michele. These assistants would have learned their craft by copying the master's drawings, preparing panels and pigments, and painting less critical parts of larger compositions. Sandro del Calzino is noted to have painted an altarpiece for the cloister of San Marco, suggesting he absorbed Sogliani's devotional style.

Sogliani's working method was reportedly meticulous and perhaps somewhat slow. Vasari notes that he was "averse to toil and quick execution," preferring a more deliberate pace. This careful approach, while ensuring a high level of finish, might have limited his overall output compared to some of his more prolific contemporaries. It's also mentioned he needed frequent rest, which could be linked to the "poor health" that ultimately led to his death at the relatively young age of 52.

His role as a representative of "High Church" painting in Florence suggests that his style aligned well with the official and more traditional tastes of ecclesiastical patrons. In an era that saw the rise of more individualized and sometimes eccentric artistic expressions with early Mannerism, Sogliani's art offered a continuation of the High Renaissance ideals of clarity, harmony, and devotional warmth.

Sogliani in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Sogliani's position, it's useful to consider him alongside other artists active in Florence during his lifetime. While he was influenced by Fra Bartolomeo and Andrea del Sarto, his work offers a contrast to the emerging Mannerist tendencies of Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1557) and Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540). These artists, his near-contemporaries, were pushing the boundaries of High Renaissance classicism with elongated figures, ambiguous spaces, jarring colors, and heightened emotionalism. Sogliani, by contrast, remained more firmly anchored in the balanced and serene aesthetic of the earlier High Renaissance.

The towering figure of Michelangelo (1475–1564) was also active during this period, though much of his career was spent in Rome. Michelangelo's dynamic energy, anatomical power, and terribilità represented a different pole of artistic expression. While the provided text suggests Sogliani's style "produced inspiration" for later artists like Michelangelo, this is a strong claim that needs careful interpretation. It is more probable that Sogliani represented a persistent and valued tradition of devotional classicism that coexisted with, and perhaps offered a counterpoint to, the more revolutionary art of figures like Michelangelo. Great masters were certainly aware of the diverse artistic currents around them.

Raphael (1483–1520), though primarily active in Rome during Sogliani's main working period, had spent formative years in Florence and his work continued to exert a powerful influence. Raphael's synthesis of grace, harmony, and clarity set a standard for High Renaissance art that resonated with Sogliani's own artistic inclinations.

The workshop tradition, exemplified by artists like Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494) in the previous generation, continued to be important. Sogliani's own workshop, though perhaps smaller in scale, was part of this system of artistic production and training.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Giovanni Antonio Sogliani continued to work throughout the 1530s and into the early 1540s. Despite his reported ill health, he produced a significant body of work. He passed away in Florence on July 17, 1544, at the age of 52.

His legacy is that of a skilled and sincere painter who contributed significantly to the religious art of his time. While he may not have been an innovator on the scale of Leonardo, Michelangelo, or Raphael, his work possessed a quiet dignity and refined beauty that was highly valued. He successfully navigated the stylistic currents of the High Renaissance, absorbing key influences while maintaining a distinct artistic personality.

Sogliani's paintings are preserved in numerous churches and museums, including the Uffizi Gallery and the Accademia Gallery in Florence, the Museo di San Marco, the aforementioned Pisa Cathedral, and internationally, for example, in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. The presence of his works in these collections attests to his historical importance and the enduring appeal of his art.

He represents a particular facet of the Florentine Renaissance – one that prioritized devotional clarity and serene beauty over dramatic innovation or intellectual complexity. His art served the spiritual needs of his community, offering images that were both aesthetically pleasing and conducive to pious contemplation. In the grand narrative of Italian Renaissance art, Giovanni Antonio Sogliani remains a notable figure, a testament to the depth and diversity of talent that flourished in 16th-century Florence. His dedication to his craft and the gentle, heartfelt piety of his works ensure his place in the annals of art history.