Giacomo Guardi stands as a significant figure in the twilight years of the Venetian school of painting. Born into an artistic dynasty, he carried forward the legacy of his celebrated father, Francesco Guardi, becoming one of the last notable practitioners of the veduta, or view painting, genre that had brought Venice's luminous beauty to the world. While often viewed through the lens of his father's fame, Giacomo developed his own distinct interpretation of the Venetian landscape, characterized by atmospheric sensitivity and a fluid, evocative brushstroke. His life and work offer insight into the continuation and transformation of artistic traditions in a changing Venice.

Family Background and Early Life

Giacomo Guardi was born in Venice in 1764, destined to be immersed in the world of art from his earliest moments. He was the son of the renowned Venetian painter Francesco Guardi (1712-1793), a master of the veduta whose works captured the ephemeral play of light and atmosphere across the city's canals and piazzas. The Guardi family's artistic roots ran deeper still. Giacomo's grandfather, Domenico Guardi (1678-1716), was also a painter, originally hailing from the Val di Sole in Trentino.

The Guardi family, originally from the mountainous Trentino region, had even been granted a title of nobility in 1643, adding a layer of historical distinction to their name. Domenico Guardi had established the family's artistic presence in Venice after studying painting, possibly absorbing influences from various Italian and perhaps even Austrian traditions given his origins and potential training path before settling in the lagoon city. Domenico's artistic endeavours laid the foundation for his sons' careers.

Francesco Guardi, Giacomo's father, along with his brother Giovanni Antonio Guardi (1699-1760), known as Gianantonio, took over Domenico's workshop. While Gianantonio focused more on figure painting and altarpieces, often collaborating with Francesco in the workshop's early days, it was Francesco who would become internationally famous for his evocative cityscapes. Growing up in this environment, Giacomo received his primary artistic education directly from his father, learning the techniques and absorbing the stylistic preferences that defined the Guardi workshop. He was trained within the family studio, a common practice that ensured the transmission of skills and styles across generations, much like the workshops of earlier Venetian masters such as Titian or Tintoretto.

Artistic Inheritance and Development

Upon Francesco Guardi's death in 1793, Giacomo inherited the family studio. This was a significant moment, placing him at the helm of a workshop with an established reputation, albeit one whose primary master had achieved widespread fame mostly posthumously. Giacomo continued the family business, focusing almost exclusively on the genre his father had mastered: the Venetian veduta. He produced numerous views of Venice, catering to a market still fascinated by the city's unique charm, even as the Venetian Republic itself was nearing its end (falling to Napoleon in 1797).

Giacomo's early work inevitably shows the strong influence of his father. He adopted Francesco's characteristic subjects – the Grand Canal, St. Mark's Square, the Rialto Bridge, lesser-known campi and canals, and views of the lagoon islands. He also employed the stylistic vocabulary he had learned in the workshop. However, as his career progressed, Giacomo began to develop subtle variations on his father's style, adapting it to his own temperament and perhaps to the changing tastes of the market.

He continued the tradition of producing views that were less about topographical accuracy, the hallmark of painters like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768) and his nephew Bernardo Bellotto (1721-1780), and more about capturing the mood and atmosphere of Venice. The Guardi approach, both Francesco's and Giacomo's, offered a more romantic, subjective interpretation of the city, emphasizing its picturesque qualities, the shimmering effects of light on water, and the bustling or sometimes melancholic life within its spaces.

Artistic Style and Technique

Giacomo Guardi's style is firmly rooted in the Venetian tradition, particularly the late Baroque and Rococo sensibilities that characterized his father's work. A key element inherited from Francesco was the pittura di tocco (painting of touch). This technique involved using small, rapid, and often distinct brushstrokes, flicks, and dabs of paint to suggest form, light, and texture rather than meticulously delineating every detail. This approach created a sense of vibrancy, movement, and atmospheric haze.

Compared to his father, Giacomo's application of the pittura di tocco could sometimes appear looser, more summary, or even slightly repetitive, especially in his smaller, more commercial works. While Francesco's touch, though free, often retained a remarkable descriptive power, Giacomo's could sometimes prioritize overall effect over specific detail. His figures, like his father's, are often rendered with quick, calligraphic strokes, becoming lively accents within the scene rather than individualized portraits.

Giacomo excelled in capturing the unique light of Venice. His works often feature soft, diffused light, particularly in views of the lagoon or scenes depicted at dawn or dusk. He paid close attention to reflections on the water, rendering them with fluid, broken brushwork that conveyed the constant motion and shimmer. While perhaps not possessing the same depth of poetic melancholy found in Francesco's best works, Giacomo's paintings successfully evoke the picturesque and romantic atmosphere of Venice. His palette often relied on silvery greys, blues, and muted earth tones, punctuated by touches of brighter color. The influence of the Rococo, with its emphasis on lightness, elegance, and decorative effects, can be felt, echoing the broader European movement perhaps seen in the works of French masters like Jean-Antoine Watteau or François Boucher, though applied to the specific context of Venetian view painting.

Representative Works

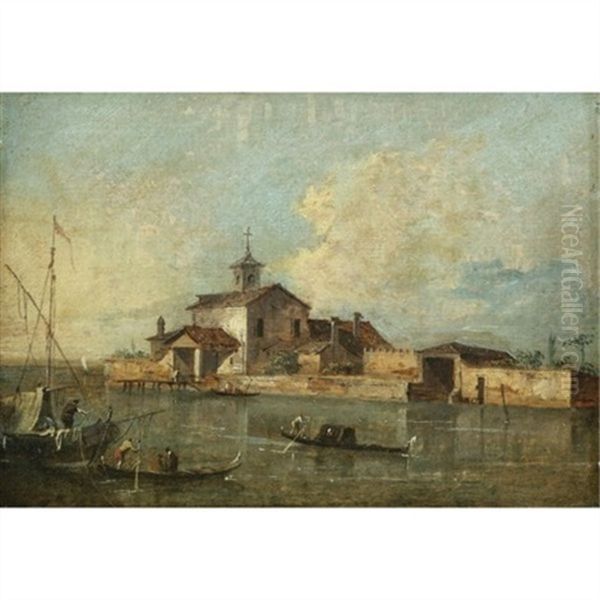

While Giacomo Guardi produced a large volume of work, often repeating popular views, certain paintings stand out as representative of his style and contribution. The provided text specifically mentions `View of the Venetian Lagoon with the Island San Giacomo di Paludo`. This title suggests a typical lagoonscape, likely emphasizing the expanse of water and sky, with the island serving as a focal point. Such works allowed Giacomo to explore atmospheric effects and the interplay of light on water, characteristic strengths of the Guardi workshop. San Giacomo in Paludo was a small island monastery, offering a picturesque subject away from the main urban center.

Another key work mentioned is `A View of Piazza San Marco`. St. Mark's Square was a perennial favorite subject for all vedutisti. Giacomo would have depicted it numerous times, likely focusing on the famous landmarks – St. Mark's Basilica, the Doge's Palace, the Campanile (bell tower), and the Procuratie buildings lining the square. His versions, following his father's example, would likely emphasize the vastness of the space, the play of light and shadow across the pavement and facades, and the lively presence of figures animating the scene, rendered with his characteristic quick brushwork.

Beyond these specific examples, Giacomo's oeuvre includes countless views of the Grand Canal with its palaces, the Rialto Bridge from various angles, smaller canals and campi (squares), churches like Santa Maria della Salute, and ceremonial events if they occurred during his active period, though perhaps less frequently than his father depicted state occasions. Many of his works were executed in gouache on paper, a medium well-suited to smaller, more portable souvenirs for tourists, alongside his oil paintings on canvas or panel.

Collaboration and Attribution

One of the complexities surrounding Giacomo Guardi's work is its relationship to that of his father, Francesco. Having trained and worked closely with his father, Giacomo absorbed Francesco's style and techniques thoroughly. This intimacy, combined with the workshop practice of producing multiple versions of popular views, has led to significant challenges in attribution for art historians. Distinguishing Giacomo's hand from his father's, especially in works produced during the period of overlap or immediately after Francesco's death, can be difficult.

The provided text notes that some works were likely collaborations, or perhaps started by Francesco and finished by Giacomo after his father's passing. Specific examples like views of the `St Mark's Campanile` and `Piazza San Cassiano` are mentioned as potentially involving both artists, leading to ongoing scholarly debate. Furthermore, Giacomo is known to have produced copies or variations of his father's most successful compositions, fulfilling market demand but further blurring the lines of authorship.

This situation is not unique in art history; the workshops of masters like Peter Paul Rubens, for instance, involved extensive collaboration and production under the master's brand. However, the stylistic similarity between Francesco and Giacomo makes the Guardi case particularly intricate. Some scholars attempt to differentiate based on perceived quality, handling of detail (Giacomo sometimes being seen as slightly harder or more schematic in architectural rendering), or overall atmospheric depth, but consensus is not always reached. This ambiguity impacts the market value and scholarly assessment of individual pieces attributed to either Guardi.

Market and Patronage

Giacomo Guardi's career unfolded during a period of significant change for Venice and for the art market. The Grand Tour, the traditional journey through Europe undertaken by wealthy young gentlemen, primarily from Britain, was still a major source of patronage for Venetian view painters in the late 18th century, although the Napoleonic Wars disrupted travel significantly. Giacomo, like his father before him, catered extensively to this market.

The demand was high for depictions of Venice as souvenirs and reminders of the traveler's experience. Giacomo specialized in producing numerous small-scale views, often in gouache but also small oils, which were more affordable and portable than the large canvases favored by earlier patrons. These works were explicitly mentioned as being sold as mementos to less affluent tourists, suggesting a tiered market strategy within the Guardi workshop.

His patrons were not limited to tourists, however. The text mentions collectors in France, Italy, and particularly Britain who acquired his works. The British fascination with Venice, fueled by literature, opera, and the Grand Tour experience itself, created a sustained demand for Venetian views. Giacomo's continuation of his father's atmospheric style appealed to this romantic sensibility. While Francesco himself struggled for recognition compared to the highly successful Canaletto during his lifetime, the Guardi name gained considerable prestige, particularly in the 19th century, benefiting Giacomo's posthumous reputation and the desirability of his works.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Giacomo Guardi is often described as the last significant painter working purely within the Venetian veduta tradition that had flourished for over a century. He represents the end of a lineage that included masters like Luca Carlevarijs (who pioneered the genre in Venice), Canaletto, Bellotto, Michele Marieschi, and his own father, Francesco. His long career extended well into the 19th century (he died in 1835), a period when Neoclassicism and Romanticism were the dominant styles elsewhere in Europe, and Venice itself had lost its political independence and economic power.

Historically, Giacomo's reputation was long overshadowed by his father's. Francesco's work underwent a major critical reappraisal in the mid-to-late 19th century, celebrated for its proto-Impressionistic qualities, its freedom of brushwork, and its poetic sensitivity. This led scholars and collectors to look more closely at the entire Guardi family output. While Giacomo was recognized as Francesco's successor, he was often judged as less original or less profound than his father.

However, modern scholarship offers a more nuanced view. Giacomo is acknowledged for successfully maintaining the family workshop and adapting its production to a changing market. His best works are appreciated for their own merits: their delicate handling of light, their charming atmospheric effects, and their continuation of a specific, highly influential vision of Venice. His style, with its emphasis on light and atmosphere conveyed through broken brushwork, is seen as a link between the 18th-century Venetian tradition and later landscape painting.

The enduring popularity of the Guardi name, coupled with the attribution difficulties, unfortunately led to the proliferation of copies and outright forgeries, further complicating the study of both Francesco and Giacomo. Nevertheless, Giacomo's authentic works are sought after by collectors and are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, confirming his status as an important, albeit secondary, master of the Venetian school. His work, like his father's, contributed significantly to the enduring visual image of Venice in the popular imagination, influencing how subsequent generations, including artists like J.M.W. Turner and later the Impressionists (Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir), would see and depict the city.

Conclusion

Giacomo Guardi navigated the complex task of succeeding a famous artistic father while working in a city undergoing profound political and cultural shifts. He faithfully carried forward the veduta tradition as practiced in the Guardi workshop, specializing in atmospheric, light-filled views of Venice that emphasized mood over meticulous detail. Using the characteristic pittura di tocco, he captured the shimmering canals, bustling squares, and evocative lagoon vistas that had captivated visitors for generations. While attribution issues and comparisons with his father Francesco complicate his legacy, Giacomo remains a recognized figure in his own right – a prolific painter who catered effectively to the tourist market and whose works continue to offer a charming, romantic glimpse into the Venice of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He stands as the final representative of a celebrated artistic dynasty and a key transmitter of the Venetian view painting tradition into a new era.