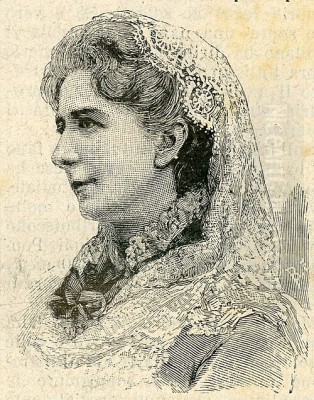

Introduction: Rediscovering a Master of Detail

Antonietta Brandeis stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century European art, particularly celebrated for her luminous and meticulously detailed views of Venice, Rome, and Florence. Born in the Austrian Empire but finding her artistic voice and lifelong inspiration in Italy, Brandeis navigated the male-dominated art world of her time with remarkable success. She carved a niche for herself, reviving and adapting the tradition of the veduta, or view painting, capturing the architectural splendour and unique atmosphere of Italian cities for an appreciative international audience. Her work, characterized by its clarity, vibrant colour, and painstaking attention to detail, continues to enchant viewers and command attention in the art market today. As an artist who bridged cultural backgrounds and overcame institutional barriers for women, her story is as compelling as the cityscapes she so masterfully depicted.

Bohemian Roots and Early Artistic Stirrings

Antonietta Brandeis entered the world on January 13, 1849, in the village of Miskowitz (Miskovice), located in Bohemia, then part of the Austrian Empire (now within the Czech Republic, though some sources mistakenly place it in modern Ukraine due to historical border shifts). Her early life was marked by change; following the death of her father, she moved with her mother to Prague. This relocation proved pivotal for her artistic development. Prague, during the 1860s, was a vibrant centre of the Czech National Revival, a movement fostering Czech language, culture, and identity, which also invigorated the local arts scene.

It was in this culturally charged environment that the young Antonietta began her formal art education. She became a pupil of the Czech artist Karel Javůrek (1815-1909). Javůrek was a respected figure known for his historical paintings and genre scenes, himself influenced by leading figures of the Czech Romantic and Realist movements, potentially including Josef Mánes (though sources sometimes list variations of this name). Studying under Javůrek provided Brandeis with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the academic traditions prevalent at the time, likely focusing on narrative clarity and historical accuracy, elements that perhaps subtly informed her later precision in architectural rendering.

Venetian Dreams: Breaking Barriers at the Academy

The allure of Italy, particularly Venice, the city that would become synonymous with her art, drew Brandeis southward. In 1867, she and her mother relocated to Venice. This move marked a crucial turning point in her life and career. Venice, with its unparalleled cityscape, rich artistic heritage, and vibrant light, offered endless inspiration. More significantly, Brandeis sought to further her education at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia (Venice Academy of Fine Arts).

Her admission to the Academy was a noteworthy achievement. In the mid-19th century, formal art academies across Europe were largely male preserves, and opportunities for women to receive rigorous, institutional training were scarce. Antonietta Brandeis became one of the very first women to be admitted as a student to the Venice Academy, breaking significant ground. This accomplishment speaks volumes about her talent, determination, and perhaps the slowly shifting attitudes towards women in the arts, however incremental.

At the Academy, Brandeis honed her skills under the tutelage of prominent professors. Her instructors included Michelangelo Grigoletti (1801-1870), known for his historical and religious paintings and portraits; Domenico Bresolin (1813-1899, often cited as Brusone in sources related to Brandeis), a significant landscape painter and photographer; Napoleone Nani (1841-1899), a respected portrait and genre painter; and Pompeo Marino Molmenti (1819-1894), another influential figure in historical and genre painting. Studying with these diverse masters exposed her to various facets of 19th-century Italian art, from academic precision to the growing interest in landscape and light.

Her time at the Academy was fruitful. She excelled in her studies, particularly in landscape painting, a genre that would define her career. In 1872, she graduated with honours, receiving awards and recognition for her talent in capturing scenic views. This academic success validated her abilities and provided a strong launchpad for her professional career as an artist in her adopted city. Her status as a pioneering female graduate of the institution remained a distinguishing feature of her biography.

The Veduta Revived: Brandeis's Artistic Style

Antonietta Brandeis is best known as a vedutista, a painter of city views, following in a tradition famously established in the 18th century by Venetian masters like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712-1793). While the Grand Tour demand that fuelled the original veduta craze had evolved, the late 19th century saw renewed tourist interest in Italy, creating a market for finely executed souvenirs of its famous landmarks. Brandeis tapped into this market with exceptional skill.

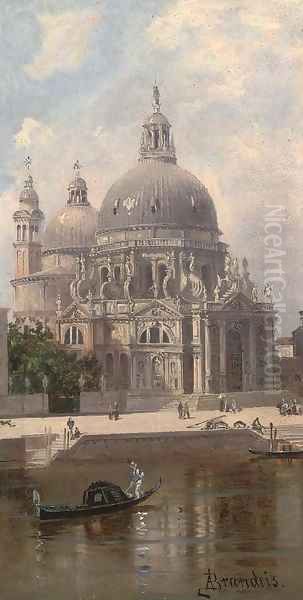

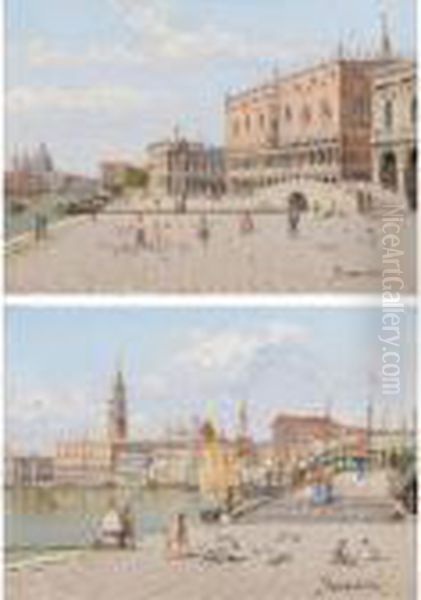

Her style, however, was distinctly of her time. While echoing the topographical accuracy of Canaletto and the atmospheric charm of Guardi, Brandeis worked within a broadly Realist framework, influenced by her academic training and contemporary trends. Her paintings are characterized by bright, clear light, crisp details, and a vibrant palette. She rendered architecture with meticulous precision, capturing the textures of stone, the play of light on water, and the intricate details of facades, bridges, and gondolas. Unlike the Impressionists, who were her contemporaries in France (like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro), Brandeis did not dissolve form into fleeting light effects but maintained a high degree of finish and clarity.

Her technique involved careful drawing and composition, often employing small, precise brushstrokes to build up surfaces and details. She had a remarkable ability to capture the specific quality of Venetian light – the sharp midday sun, the soft glow of dawn or dusk – and its reflection on the canals that are central to so many of her compositions. While Venice was her primary muse, she also applied this detailed, luminous style to views of other Italian cities, including Rome, Florence, and Bologna, demonstrating her versatility within the veduta genre. Her work offered viewers an idealized yet recognizable vision of Italy's famed beauty.

Capturing Italy: Key Themes and Representative Works

The heart of Antonietta Brandeis's oeuvre lies in her depictions of Venice. She painted the city's iconic landmarks repeatedly, often varying the viewpoint, time of day, or incidental figures to create unique compositions based on popular demand. St. Mark's Square (Piazza San Marco), the Doge's Palace, the Rialto Bridge, the Grand Canal, Santa Maria della Salute, and smaller, picturesque canals and bridges were all frequent subjects. Works like Venice, Santa Maria della Salute (c. 1900) or Venice Piazzetta (c. 1890) exemplify her ability to combine architectural accuracy with a sense of bustling life or serene beauty.

Her painting Ponte del Casin sul Rio di San Vio, Venice, which fetched a significant price at auction, showcases her skill in depicting quieter, more intimate corners of the city, capturing the interplay of water, architecture, and light away from the grandest vistas. She often included small figures – gondoliers, elegantly dressed ladies, locals going about their day – which add scale and animation to her scenes, enhancing their narrative quality and appeal to tourists seeking glimpses of Venetian life.

Beyond Venice, Brandeis demonstrated her skill with Roman and Florentine scenes. Her depiction of the Arch of Drusus, Rome (late 19th century) shows her careful attention to ancient monuments, rendered with the same clarity and sensitivity to light as her Venetian works. A painting like Florence, View of Palazzo Vecchio from the Boboli Gardens (1890s) captures the distinct character of the Tuscan capital, showcasing her ability to adapt her style to different urban environments and architectural forms.

Brandeis also undertook religious commissions. Notably, she painted at least three altarpieces for churches in Dalmatia (present-day Croatia), a region with strong historical ties to Venice. These works, less known than her vedute, demonstrate her versatility and connection to the traditions of Venetian religious painting, perhaps influenced by her teacher Grigoletti. An early work exhibited in 1870, Cascina della Madonna di Varese, suggests an early interest in landscape subjects beyond the purely urban, though cityscapes would ultimately dominate her output.

Career, Exhibitions, and the Market

Antonietta Brandeis actively pursued a professional career from early on. Her participation in the exhibition of the Società Veneta Promotrice di Belle Arti (Venetian Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts) began as early as 1870, even before her official graduation, indicating her ambition and early recognition. She continued to exhibit regularly in Venice, Florence, and Rome throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

Her meticulously crafted and brightly coloured vedute found particular favour with foreign visitors, especially British and Austrian tourists undertaking their own versions of the Grand Tour. These travellers sought high-quality mementos of their Italian sojourns, and Brandeis's works, often painted on a modest scale suitable for transport, perfectly met this demand. Her paintings offered a more permanent and artistic alternative to the burgeoning market for photographs, though photography, pioneered in Venice partly by one of her teachers, Domenico Bresolin, undoubtedly influenced the desire for accurate city views.

Recognizing the strength of the international market, Brandeis increasingly focused her efforts on selling abroad, particularly to London-based dealers and collectors. While she maintained her studio in Venice for most of her active career, she gradually participated less in Italian exhibitions. This focus on the international, particularly British, market explains why many of her works are found in UK collections and frequently appear in British auction houses. Her consistent sales and the prices her works continue to achieve at auction attest to her commercial success during her lifetime and her enduring appeal to collectors. She operated shrewdly within the art market of her time, understanding her audience and catering to its tastes while maintaining a high standard of execution.

Context: The Venetian Art Scene in the Late 19th Century

Antonietta Brandeis worked in Venice during a period of transition for the city's art scene. The glories of the Renaissance and the 18th-century vedutisti like Canaletto and Guardi cast long shadows. While Venice was no longer the independent republic it once was (having become part of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy in 1866), it remained a powerful magnet for artists and tourists. The Academy where Brandeis studied was a central institution, upholding traditional training methods but also adapting to new artistic currents.

Her contemporaries in Venice included artists exploring different facets of Venetian life and landscape. Giacomo Favretto (1849-1887), her exact contemporary, gained fame for his lively, colourful genre scenes depicting everyday Venetian life, often with a charming, anecdotal quality. Guglielmo Ciardi (1842-1917) and his sons, Beppe and Emma Ciardi, were renowned landscape painters, capturing the Venetian lagoon and mainland countryside with a fresh, atmospheric approach that sometimes bordered on Impressionism. Luigi Nono (1850-1918, the painter, not the composer) was known for his emotionally charged genre scenes and portraits.

Earlier in the century, Ippolito Caffi (1809-1866) had already revitalized the veduta genre with a more Romantic sensibility, dramatic light effects, and unusual viewpoints, bridging the gap between the 18th-century masters and Brandeis's generation. While Brandeis's detailed realism set her apart from the looser brushwork of Favretto or the atmospheric focus of Ciardi, she shared with them a deep engagement with Venice as a subject. Her specific niche was the highly finished, detailed view that appealed strongly to the tourist market, a continuation and adaptation of the Canaletto tradition. Federico Moja (1802-1885), another vedutista active in Venice, represented an older generation whose work might also have provided a reference point for Brandeis. Her success suggests she found a distinct voice amidst these varied artistic currents.

Context: Women Artists Navigating a Male World

Antonietta Brandeis's career unfolds against the backdrop of significant, though slow, changes for women artists in the 19th century. Historically, women had faced substantial barriers to professional art careers. Access to formal training, particularly life drawing classes involving nude models (considered essential for history painting, the most prestigious genre), was often restricted. Societal expectations frequently confined women to the domestic sphere or limited their artistic pursuits to "appropriate" genres like portraiture, still life, or watercolour miniatures.

Despite these hurdles, the 19th century saw a growing number of women challenging these limitations and achieving professional recognition. Brandeis's admission to the Venice Academy was part of this broader trend. In France, artists like Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) achieved international fame for her animal paintings, even obtaining special permission to wear men's clothing to visit slaughterhouses for study. Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) and the American Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) were central figures in the Impressionist movement in Paris, exhibiting alongside their male colleagues like Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, though still facing unique challenges related to their gender.

Brandeis's path was different from the Parisian avant-garde, focusing on a more traditional genre and market. However, her success as a professional artist, running her own studio, managing international sales, and achieving financial independence through her work, was a significant accomplishment for a woman of her era. Her ability to thrive within the established structures of the Academy and the commercial art market, specializing in a demanding genre like the veduta, highlights her skill, business acumen, and determination. She stands as an important example of a female artist who built a successful and respected career within the specific context of late 19th-century Italy.

Later Life, Marriage, and Legacy

In 1897, at the age of 48, Antonietta Brandeis married Antonio Zamboni, a Venetian knight and officer of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. This marriage likely enhanced her social standing in Venice. However, her married life was relatively short; Zamboni passed away in 1909. Following her husband's death, Brandeis left Venice, the city that had been her home and primary inspiration for over four decades.

She relocated to Florence, where she spent her remaining years. She continued to paint, though perhaps less prolifically than before. Her connection to Florence deepened through her philanthropic activities. Upon her death on March 20, 1926, Antonietta Brandeis bequeathed a significant portion of her estate, including potentially some of her artworks, to the Pia Casa di Lavoro (now Istituto degli Innocenti), a large orphanage in Florence. This final act reflects a charitable spirit and a desire to support her adopted Tuscan community.

Antonietta Brandeis's legacy endures primarily through her paintings. Her vedute of Venice, Florence, and Rome remain highly sought after by collectors. They are appreciated for their technical brilliance, their vibrant depiction of iconic Italian cityscapes, and their nostalgic charm. Her works serve as beautiful documents of these cities as they appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, capturing a world on the cusp of modernity. Beyond the aesthetic appeal, her career serves as an important case study of a successful female artist operating within the academic and commercial structures of her time, overcoming barriers to education and professional practice. She demonstrated that women could excel in demanding genres and achieve international recognition and financial success through their art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Italy

Antonietta Brandeis occupies a unique and respected place in the history of 19th-century European art. As a Bohemian-born artist who found her true calling under the Italian sun, she masterfully adapted the veduta tradition to the tastes and demands of her era. Her meticulous attention to detail, brilliant handling of light and colour, and unwavering focus on the architectural beauty of Venice, Rome, and Florence resulted in a body of work that continues to captivate.

Her journey from Prague to the forefront of the Venetian art market, including her pioneering role as one of the first women to study at the Venice Academy of Fine Arts, underscores her talent and tenacity. While contemporaries like Favretto explored genre scenes or Ciardi pursued atmospheric landscapes, Brandeis carved her own path, creating highly finished, luminous cityscapes that appealed to an international clientele. Her paintings are more than just topographical records; they are vibrant, idealized visions of Italy's most celebrated cities, imbued with a sense of timeless beauty. Through her art and her life story, Antonietta Brandeis remains a compelling figure, a testament to female artistic achievement and the enduring allure of the Italian landscape.