Luca Carlevarijs stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Italian art, particularly renowned for his foundational role in the development of Venetian view painting, known as veduta. Active during the late Baroque and early Rococo periods, Carlevarijs was not only a painter but also a skilled etcher and architect. His meticulous and panoramic depictions of Venice set the stage for the genre's flourishing in the 18th century, profoundly influencing the subsequent generation of artists who would bring Venetian vedute to international fame. His life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic landscape of Venice at a time when the city was a major center of European culture and a primary destination for Grand Tour travelers.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Luca Carlevarijs was born in Udine, a city in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy, then part of the Republic of Venice, in 1663. His father, Giovanni Leonardo, was reportedly a painter and architect, suggesting an early exposure to the arts. Following his father's death, the young Luca moved to Venice in 1679, where he would spend the majority of his prolific career. Venice, with its unique topography, stunning architecture, and vibrant ceremonial life, provided the ideal subject matter for his developing artistic interests.

Details about his early training remain somewhat scarce, but it is widely accepted that a crucial influence came from his time spent in Rome. While the exact dates are debated, Carlevarijs likely visited the papal city in the late 17th century. There, he would have encountered the work of artists specializing in cityscapes and landscapes. Among the most significant influences was the Dutch painter Caspar van Wittel, known in Italy as Gaspare Vanvitelli. Van Wittel was a key figure in establishing the veduta genre in Rome, known for his topographically accurate and light-filled views of the city. Carlevarijs absorbed Vanvitelli's approach to perspective, clarity, and detailed rendering of urban environments, adapting these principles to the distinct context of Venice.

Upon his return or establishment in Venice, Carlevarijs found support among the city's aristocracy. He gained the patronage of the prominent Zenobio family, who provided him with accommodation and support. This connection was so strong that he was sometimes referred to by the nicknames "Luca Casanobrio" or "Luca di Ca Zenobio," directly linking him to his benefactors. This patronage was crucial in enabling him to establish his workshop and pursue his artistic vision, focusing on the burgeoning market for views of Venice.

The Emergence of the Venetian Veduta

Before Carlevarijs, depictions of Venice often existed within narrative paintings or as somewhat stylized map-like views. Carlevarijs is credited with being one of the first artists in Venice to specialize in the veduta as an independent genre, treating the city itself as the primary subject. His approach was characterized by a commitment to topographical accuracy, employing careful observation and potentially optical aids like the camera obscura to achieve precise perspectives and detailed architectural renderings.

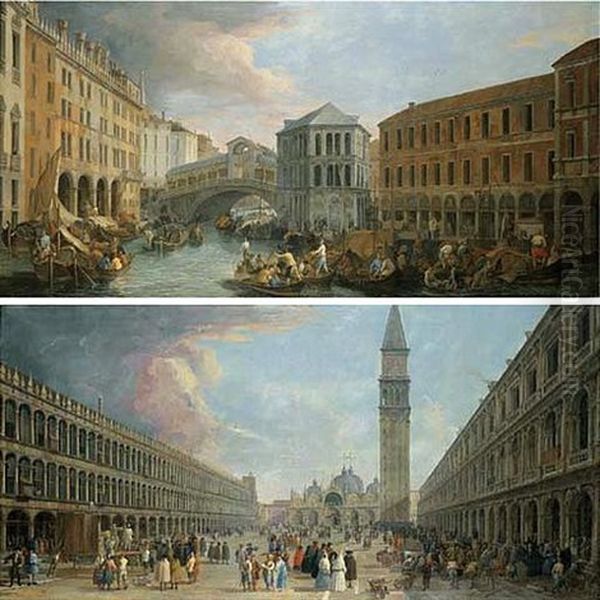

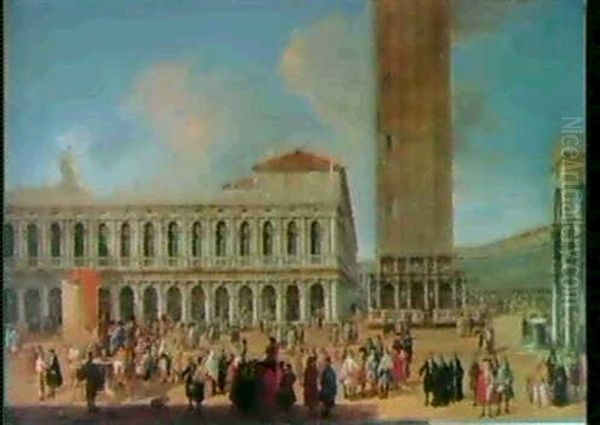

His style can be described as objective and almost scientific in its meticulousness. He focused on capturing the specific structures, piazzas, and canals of Venice with remarkable clarity. Unlike the more atmospheric or romanticized views that would later be popularized by artists like Francesco Guardi, Carlevarijs's work emphasized structure, perspective, and the accurate documentation of the urban fabric. His paintings often feature wide-angle perspectives, encompassing broad vistas of iconic locations like St. Mark's Square, the Piazzetta, the Grand Canal, and the Rialto Bridge.

The figures populating his scenes, known as macchiette (little spots), are typically small in scale relative to the grand architectural settings. They serve to animate the views and provide a sense of daily life or depict specific events, such as diplomatic receptions or festivals, but the architecture and cityscape remain the dominant focus. His handling of light is generally clear and even, illuminating the details of the buildings without the dramatic chiaroscuro found in some Baroque painting or the shimmering, dissolved light of later Rococo masters.

Masterworks: Paintings of Ceremonial Venice

Carlevarijs excelled in capturing the public face of Venice, particularly the elaborate ceremonies and diplomatic events that were integral to the Republic's identity and international relations. These paintings were highly sought after by both local patrons and foreign visitors, especially those undertaking the Grand Tour who wished to acquire sophisticated souvenirs of their time in the Serenissima.

One notable example is The Entry of the French Ambassador into Venice, depicting the arrival of Henri Charles Arnauld de Pomponne in 1706. Housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, this work showcases Carlevarijs's ability to combine architectural precision with the pageantry of a state occasion. The composition carefully delineates the Doge's Palace and surrounding structures while capturing the bustling activity of gondolas and figures involved in the procession.

Similarly, The Reception of the British Ambassador Charles Montagu, Earl of Manchester, at the Doge's Palace, dated 1707 and now in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, documents another significant diplomatic event. Carlevarijs meticulously records the architecture of the Piazzetta and the Doge's Palace, framing the ceremonial arrival of the ambassador. These works served not only as artistic achievements but also as historical documents, recording specific moments in Venetian diplomatic history.

Another celebrated painting is The Regatta on the Grand Canal in Honor of Frederick IV, King of Denmark, painted around 1711 and held by the J. Paul Getty Museum. This vibrant work captures the excitement and spectacle of a Venetian regatta, a traditional boat race held on special occasions. Carlevarijs masterfully depicts the crowded Grand Canal, lined with decorated boats (bissone) and spectator-filled palaces, demonstrating his skill in handling complex compositions with numerous figures and intricate architectural backdrops. Works like The Piazzetta, Venice (c. 1700, Timken Museum of Art) show his ability to capture iconic views even without a specific event, focusing on the architectural grandeur and daily life of the city.

Le Fabriche e Vedute di Venetia: A Monumental Etching Project

Beyond his paintings, Carlevarijs made a lasting contribution through his work as an etcher. His most significant achievement in this medium is the collection titled Le fabriche e vedute di Venetia, disegnate, poste in prospettiva et intagliate da Luca Carlevarijs (The Buildings and Views of Venice, Drawn, Put into Perspective, and Engraved by Luca Carlevarijs). Published in 1703, this series comprises 104 etchings depicting the principal buildings, squares, and views of Venice.

This collection was groundbreaking for its time. It represented the most comprehensive and systematically organized visual record of Venice produced to date. The etchings are characterized by the same commitment to perspective and architectural detail found in his paintings. Carlevarijs presented iconic landmarks alongside lesser-known corners of the city, offering a remarkably thorough topographical survey. The publication was immensely influential, serving as a model for subsequent print series and providing artists, architects, and travelers with an invaluable resource.

Le fabriche e vedute di Venetia solidified Carlevarijs's reputation and disseminated his vision of Venice far beyond the reach of his individual paintings. Copies were acquired by collectors across Europe, including notable figures like King George III, whose collection is now partly housed in The British Library. The Museo Correr in Venice also holds examples of these important prints. The series not only documented the city but also helped to codify the canonical views of Venice that would dominate the veduta genre for the next century.

Artistic Technique and Critical Reception

Carlevarijs's technique was rooted in careful observation and precise draughtsmanship. His preparatory drawings and the detailed nature of his finished works suggest a methodical process. While not definitively proven, it is highly likely he utilized a camera obscura, a device that projects an image onto a surface, aiding artists in achieving accurate perspective and capturing complex details. This tool was increasingly popular among vedutisti in the 18th century.

His compositions are often characterized by strong linear perspective, typically employing a single vanishing point or a slightly elevated viewpoint to encompass wide panoramas. The architectural elements are rendered with sharp lines and meticulous attention to detail, from window tracery to decorative stonework. His palette tends towards cooler tones compared to the warmer, more luminous palettes of later Venetian painters like Canaletto or Tiepolo. The overall effect is one of clarity, order, and objective representation.

While celebrated for his precision, Carlevarijs's work has occasionally faced criticism. Some art historians have pointed out minor inaccuracies in architectural proportions or spatial relationships in certain works. These critiques, however, often arise from comparisons with the almost photographic realism achieved by his successor, Canaletto. It's important to view Carlevarijs within his context as a pioneer establishing the conventions of the genre. His primary goal was often a recognizable and comprehensive depiction rather than absolute mathematical precision in every detail.

Furthermore, some debate has arisen regarding the relationship between Carlevarijs and Canaletto, particularly concerning originality. Scholars have noted instances where Canaletto appears to have drawn inspiration from, or directly adapted compositions found in, Carlevarijs's paintings and etchings, especially in his earlier works. This has led to discussions about influence versus imitation, a common theme in art history when a pioneering figure is followed by a highly successful successor.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping the Venetian School

Luca Carlevarijs's most significant legacy lies in his profound influence on the subsequent generation of Venetian view painters. He effectively laid the groundwork for the golden age of the veduta, establishing the compositional formulas, subject matter, and technical standards that would be adopted and adapted by his successors.

The most famous artist indebted to Carlevarijs is Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known as Canaletto. Canaletto, who began his career as a theatrical scene painter, turned to veduta painting around 1719. His early views of Venice clearly show the influence of Carlevarijs in their choice of subjects, compositional structures, and detailed rendering. Canaletto adopted and refined Carlevarijs's use of perspective and topographical accuracy, eventually developing his own signature style characterized by brighter light, more dynamic atmospheric effects, and an unparalleled level of detail that captivated the European market. While Canaletto acknowledged his predecessor's impact, his own innovations ultimately surpassed Carlevarijs in fame and market appeal during his lifetime.

Another major figure influenced by Carlevarijs was Francesco Guardi. Guardi, along with his brother Gian Antonio Guardi, initially worked in figure painting before turning increasingly to vedute, particularly after Canaletto's departure for England. Guardi's early view paintings often show a clear debt to Carlevarijs's compositions and style. However, Guardi's later work diverged significantly, moving towards a more painterly, atmospheric, and emotionally evocative style. His vedute feature flickering light, looser brushwork, and a sense of transience, contrasting sharply with Carlevarijs's precise objectivity.

Beyond Canaletto and Guardi, Carlevarijs's influence extended to other artists working in the genre. Michele Marieschi, another contemporary vedutista, worked in a style that sometimes echoed Carlevarijs's precision, though often with more dramatic perspectives and contrasts of light and shadow. Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto's nephew and pupil, carried the tradition of detailed view painting to other European capitals like Dresden, Vienna, and Warsaw, building upon the foundations laid by both Carlevarijs and his uncle.

Carlevarijs's work should also be seen within the broader context of the Venetian art scene of his time. While he specialized in vedute, Venice was bustling with renowned artists in other genres. The great decorative painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo was creating vast frescoes and canvases filled with light and movement. Rosalba Carriera was achieving international fame with her delicate pastel portraits. History painters like Sebastiano Ricci and landscape artists like his nephew Marco Ricci were also highly active, contributing to the city's vibrant artistic milieu. Pietro Longhi documented the intimate scenes of Venetian daily life. Carlevarijs's focus on the cityscape provided a distinct but complementary vision of Venice during this rich artistic period.

Patronage, Market, and Collections

Carlevarijs enjoyed considerable success during his lifetime. His patrons included not only Venetian nobles like the Zenobio family but also foreign diplomats, merchants, and affluent travelers on the Grand Tour. The demand for accurate and impressive views of Venice was growing rapidly, fueled by the city's status as a cultural capital and tourist destination. Carlevarijs's ability to capture both the iconic landmarks and the ceremonial splendor of the Republic made his works highly desirable.

His paintings documenting ambassadorial receptions were likely commissioned or purchased by the diplomats themselves or by Venetian officials involved in the events. The large scale and detailed execution of these works suggest significant commissions. His etchings, being more affordable and reproducible, reached an even wider audience, helping to shape the popular image of Venice across Europe.

Today, Luca Carlevarijs's works are held in major museums and collections worldwide. Besides the aforementioned J. Paul Getty Museum, Timken Museum of Art, Rijksmuseum, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, The British Library, and Museo Correr, his paintings and prints can be found in institutions such as the Liechtenstein Collection in Vienna, the National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. His presence in these collections attests to his historical importance and artistic merit.

Significant exhibitions have also helped to shed light on his contributions. Exhibitions focusing on Venetian view painting or the art of the 18th century frequently include his works, often placing them in dialogue with those of Canaletto and Guardi. For instance, exhibitions at the National Gallery, London, have explored the relationships and stylistic developments among these key vedutisti. Shows at institutions like the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have featured his paintings as prime examples of the genre. An exhibition at Palazzo Chiericati in Vicenza included his work as part of a survey of Venice's artistic golden age.

Re-evaluation and Conclusion

Luca Carlevarijs died in Venice on February 12, 1730. Despite his pioneering role and contemporary success, his fame was later eclipsed by that of Canaletto and, to some extent, Guardi. For a long period, he was often regarded primarily as a precursor, a competent but perhaps less brilliant forerunner to the masters who followed. However, art historical scholarship in recent decades has led to a significant re-evaluation of his work and importance.

Today, Carlevarijs is recognized not just as an influence but as a major artist in his own right. His development of the Venetian veduta as a distinct and respected genre was a crucial achievement. His meticulous attention to detail, sophisticated understanding of perspective, and ability to capture the unique character of Venice laid the essential foundation upon which the entire school of Venetian view painting was built. His monumental etching project, Le fabriche e vedute di Venetia, remains a landmark in topographical printmaking and a vital record of 18th-century Venice.

While his style may lack the dazzling light of Canaletto or the evocative atmosphere of Guardi, Carlevarijs's work possesses its own distinct qualities: clarity, precision, and a powerful sense of place. He offered a vision of Venice that was both accurate and grand, perfectly suited to the tastes and demands of his time. As the artist who truly launched the genre that would become synonymous with Venetian art in the 18th century, Luca Carlevarijs holds an undeniable and enduring place in the history of European art. His paintings and etchings continue to provide invaluable insights into the appearance and life of the Venetian Republic during its final century of splendor.